When Pascal Khoo Thwe was a boy, growing up among Padaung tribesmen in remote southeast Burma, his grandmothers and aunts wore broad rings of gold around their necks, each weighing about a pound, and they added more, year by year. He recalls that his grandmother’s “rings were fourteen inches high and rose to her head as though they were supporting a pagoda.” This was in the 1970s and the “giraffe-necked” Padaung women have largely disappeared.

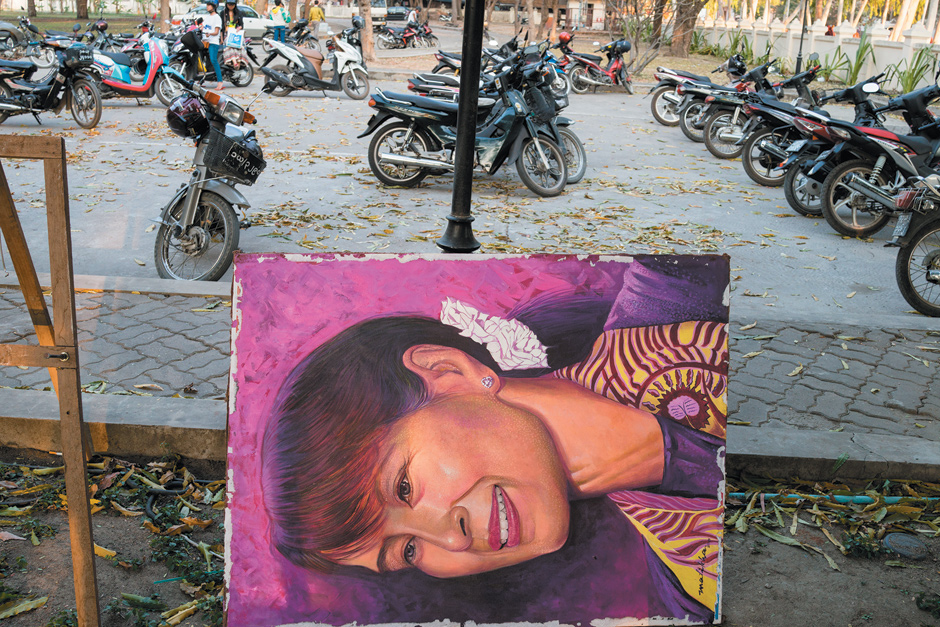

In 2002 Khoo Thwe published From the Land of Green Ghosts, a highly acclaimed memoir of childhood and escape from the military dictatorship that ruled his native land from 1962 to 2011. As Burma emerges from half a century of seclusion and repression, his book is now on sale throughout the country, particularly at the gates of pagodas and along the fast-developing tourist routes, along with pirated copies of Burmese Days, George Orwell’s mordant attack on British colonialism, written after he served as a policeman in Burma in the 1920s.

In February, Khoo Thwe was one of the speakers at Burma’s second Irrawaddy Literary Festival, held this year in Mandalay. Set up by Jane Heyn, the wife of a former British ambassador, the festival is proving highly successful in lending a platform to long-silenced writers—some sixty of whom attended—while providing them with contacts to Western literary agents and publishers. The presence of a handful of them, scouting for new authors, may mean that some of the least known and translated literature in the world will finally find an international audience.

Over the last few years, ever since the military lifted its stranglehold on most aspects of Burmese life, there has been a remarkable explosion in writing. Much of it is historical and political, feeding what writers at the festival described as an overwhelming hunger among the people to learn more about what went on in their country during the dark years. Fearful that their new freedoms might again be curtailed, many feel an urgency to get their stories down on paper and published—and, if possible, translated—as quickly as possible. While no writers are said to remain in jail today, a group of journalists is awaiting trial for reporting on a secret military installation; and even as the festival was beginning came the news that the three- or six-month visa until recently accorded to foreign reporters may be reduced to one month.

The military dictators were not the first to assault Burmese writers, who for centuries cultivated a gentle, poetical style, full of intricate rhymes and delicate allusions, that was most suited to poetry and the telling of tales. With the arrival of the British occupiers in 1824 came a demand for practical, utilitarian speech, much at odds with a largely Buddhist people for whom education meant not just book learning, but mastery of the supreme knowledge that would lead to enlightenment. It is revealing that when the Nagani, or Red Dragon, book club began to make available at low cost translations of Western books in the 1930s, thirty-eight were on the subject of war, thirty-two on revolution, and fifteen on fascism. More importantly, they coincided with the emergence of a new school of poetry, Khitsan—“testing the times”—with verses that were both formal and progressive, viewing classical themes from new angles, and this poetry became crucial in the growing nationalist movement against colonialism.

The invasion by Japanese forces in 1942 was initially greeted with some excitement, as another step toward liberation from the British, but it was not long before their fellow Asians, whose achievements the Burmese had admired, proved as brutal and hated as the British. After the war, Aung San Suu Kyi’s father, General Aung San, led the country to independence. But by 1947, the general was dead, murdered together with much of his cabinet by a rival faction, and Burma was struggling to negotiate its way to democracy against a background of ethnic conflicts—the country has ten major ethnic groups and over one hundred subgroups—and a powerful Communist insurgency backed by China.

The coup led by another army officer, General Ne Win, in 1962 was largely bloodless, but it was not long before foreign businesses were closed by the military and tourist visas limited to twenty-four hours; demands by ethnic minority groups for autonomy, promised at independence, were met by military repression. The army and the secret police became the ruling castes.

Burma closed its doors to the outside world, under what the poet Maung Yu Py called “the great ice sheet.” A country that had been rich in minerals, precious stones, teak, and natural gas sank into decline. Rangoon University, once the foremost in Asia, soon became its most impoverished. Writers who were too outspoken found themselves locked up; some would spend years manacled to the walls of their solitary cells.

Advertisement

It was in the spring of 1988 that a brawl in a Rangoon tea shop sparked what would turn into a very brief Burmese spring. Students, teachers, artists, doctors, and office workers took to the streets. In a surprise move General Ne Win stepped down. But other generals were soon firing on the marchers, and bodies were seen floating in the Irrawaddy River. Thousands of young people like Pascal Khoo Thwe fled to the border to escape arrest. Aung San Suu Kyi, who had been living abroad with her British husband and her two sons, happened to be in Burma at the time, nursing her ill mother. Swept into setting up the opposition National League for Democracy, she was soon detained in what would be repeated periods of house arrest.

Her party, despite a clear majority in the elections of May 1990—winning 392 out of 492 seats—was not allowed to take office. Burma was renamed Myanmar. Another eleven years would pass before General U Thein Sein, prime minister of the military government, took off his uniform and became the civilian president, promising reform of the labor laws, the release of political prisoners, and the easing of censorship. Released from house arrest, Aung San Suu Kyi, who is the patron of the literary festival, embarked on the political life so long denied her.

The censorship of the dark years was draconian. Writers were forbidden to mention politics, most current affairs, prisons, or any matter that reflected badly on the military. They were allowed to meet visiting foreigners only with government permission. The words “sunset” (Ne Win’s name meant “sunrise”), “red” (the Communists), and “mother” (the name often given to Aung San Suu Kyi) were banned. AIDS, leprosy, and hunger were prohibited topics. Before publication, every sentence written had to be submitted to the Press Censorship Board, and the elimination of words made nonsense of most texts. It was, says the short-story writer Tin Moe, “like taking your heart away.”

But censorship, as Jorge Luis Borges famously wrote, is the “mother of metaphor.” And in this literary battle for expression, Burma’s writers—particularly poets, as poetry was and remains the most popular form of literature—struggled to find images, allusions, and humor in which to say what they wanted, ever mindful of the censors’ heavy black ink and the danger of retribution to their families. “At this time,” wrote Tin Moe, “We are not poetry,/We are not human,/This is not life,/This is just so much waste paper.” “Now my head,” wrote a younger poet, Thitsar Ni, “Is trapped/In ill-fitting shoes.”

Weather, rivers, water, geography, natural calamities, and even body hair became metaphors for a political system that many feared would never lessen its grip. “We became highly skilled at self-censorship,” says Dr. Aung Myint, rector of the University of Traditional Medicine in Mandalay, who earlier this year brought out a thousand-page compilation of all the underground writing and press reports that accompanied the 1988 uprising. “At night, we copied banned authors, by hand and typewriter and carbon paper and passed them among our friends.” Aung San Suu Kyi’s Freedom from Fear, first published in the UK in 1991, the year that she was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize, was circulated widely in samizdat for almost twenty years before it became legally available in Burma.

Freed from censorship, poets are now experimenting with a range of forms and styles, though “unlearning self-censorship,” as the poet Pandora puts it, is not easy. There have already been poems about the Arab Spring and the harsh treatment of Burmese farmers, as well as satires on power cuts, while a “post-88 generation,” born after the uprising, is grappling with the question of how you shed such a heavy history. One of the best-known poets, Zeyar Lynn, warns that it is important not to overwhelm the “P of poetry” with the “P of politics.” Though the print run on each was small—on average one thousand copies—a hundred titles of verse were published in the last year. In 2012 came a first anthology of Burmese poets, Bones Will Crow, edited by another of Burma’s most-loved poets, Ko Ko Thett, and James Byrne; Thett posts his poems straight on the Internet and e-mails them to readers.

These poets are often published first in the many literary journals that have long been a feature—even during the dictatorship—of Burma, alongside short-story writers. Novelists remain rare. A notable exception is Nu Nu Yi, whose Smile as They Bow has become a best seller at home and been widely sold in translation. Like the “post-88 generation,” Nu Nu Yi is not concerned with history. Her novel is set at the Taungbyon festival held near Mandalay every year, and her heroine is a cynical, aging, gay transvestite and medium—a natkadaw—who fears that she is losing her young lover to a woman. Switching between the first person and the third, Smile as They Bow is earthy and quirky in tone.

Advertisement

As the military became ever more cunning at arresting dissident writers, those who had the means to escape arrest went into exile. In the memoirs of the lost years, exile is an ever-present theme. In From the Land of Green Ghosts, Pascal Khoo Thwe, who spent twenty-four years abroad before returning to Burma last year, tells of stumbling, as a young student at Mandalay University in the early 1980s, on the works of James Joyce, Jane Austen, and T.S. Eliot in battered copies left over from the years of British rule and circulating them among his friends. At the time, he was financing his studies by working in a restaurant. His first encounters with “half-dressed,” hairy, pungent-smelling Westerners appalled him. Their “massive, sweaty bodies lumbering into our restaurant” reminded him of “white buffalos who had just completed a day’s ploughing in the fields.”

When he was forced to flee Mandalay, leaving friends dead or in jail, and spent months on the Thai border with the rebels, it was one of these white buffalos who came to his aid. John Casey was a British lecturer in English at Cambridge when, during a very brief visit to Mandalay, he met the Joyce-loving young Pascal and arranged to bring him to Cambridge, where in time he became the first Burmese to get an honors degree in English literature there. His greatest problem, Khoo Thwe writes, was not so much the demands of reading Chaucer, Milton, and Shakespeare, but learning to think for himself, “having to cope intelligently” with intellectual freedom, and not to feel ashamed of expressing his own opinions, which he feared might somehow seem ungrateful to his generous benefactor.

In literary matters, exile was equally kind to Thant Myint-U, the grandson of U Thant, the UN secretary-general, whose The River of Lost Footsteps provides an excellent introduction to the tangled story of modern Myanmar along with a personal odyssey not altogether unlike Khoo Thwe’s. As the son of Myanmar’s ambassador to the US, he grew up in Washington and was educated at Harvard, but the 1988 uprising effectively prevented further return visits to his home country. Like Khoo Thwe, he briefly joined the rebels on the border, before working for Human Rights Watch and as a UN peacekeeper in Phnom Penh and Sarajevo. The River of Lost Footsteps, a book that is at the same time scholarly and hugely enjoyable, is also now freely on sale throughout Burma, despite its author’s fierce criticism of the military and the way that it made of isolation “not an ideology but a mentality.”

A more recent memoir of the years of repression is Golden Parasol, by Wendy Law-Yone, a novelist who has lived in exile since leaving the country soon after the 1962 coup.1 Subtitled A Daughter’s Memoir of Burma, it traces the life of her father Edward, a courageous and crusading editor and proprietor of the country’s most outspoken newspaper, The Nation, before and during the early years of the dictatorship. Edward Law-Yone, who was possessed of a steely determination and a bumptious, impatient nature, bequeathed his papers to his daughter, not long before dying in exile in the US in 1980. For many years she was unable to face them, but when at last she did, she discovered that her father had a wonderful story to tell, and that by writing about his turbulent life, she could map the recent history of Burma itself.

Edward Law-Yone began his working life on the Burmese railways before starting, with no money and no real premises, the newspaper that would become the most troublesome to the military generals. Arrest was not long in coming. Freed after five years in prison, he tried to restore democracy from the Thai border, and when that failed he took his family to the US. Though he was never able to go home, he told his children that his was a “temporary exile.” Burma, he said, is “where we belong and where you will all eventually put down your roots.” When she arrived to attend the literary festival in Mandalay in February, Wendy Law-Yone had been in exile for over forty years.

Most Burmese writers were not, of course, as fortunate. Trapped by lack of money and by family responsibilities, they ceased writing altogether, or devised ever more ingenious ways of bypassing the censors. Many went to jail. Together with the memoirs of the dictatorship years, the last eighteen months have seen the publication of a number of prison diaries and more are appearing all the time, responding, says Dr. Aung Myint, to “a voracious desire for firsthand reports written by victims.”

One of the starkest was written by Ma Thanegi, Nor Iron Bars a Cage. She spent almost one thousand days, between 1989 and 1992, in Yangon’s Insein Prison after she was arrested following the 1988 uprising. Ma Thanegi was an artist in her early forties, divorced and with no children, when she offered her services to Aung San Suu Kyi, who was briefly freed from house arrest, and found herself putting together posters and leaflets for the National League for Democracy and acting as Aung San’s personal assistant.

These were heady days and many of the young supporters went through the Buddhist rites of blessing for the dead, saying that they wanted to be certain of departing this life in good spiritual order in case the generals attacked again. When they did, and a new military body called the State Law and Order Restoration Council declared war on all those who had supported Aung San Suu Kyi, Ma Thanegi was among thirty of her closest aides who were put in Insein Prison.

Constantly interrogated but never tried, kept alone in a cell and allowed neither books nor paper, she kept despair at bay through friendship with the other prisoners, arguing to herself that there were no other circumstances in life in which she would have an opportunity to meet such a wide array of women: prostitutes, drug dealers, and every kind of political activist. To distract herself, she saved and reared young sparrows who flew inadvertently into her cell, made small cloth turtles out of material sent by the seamstress wife of a kind guard, and insisted on always wearing lipstick to keep up her morale. Worrying that she might lose her touch as a painter, she painted in her mind, and by the time she emerged from prison had also completed two novels and committed them to memory.

Nor Iron Bars a Cage is rich in detail—of prison food, conversations, stories, the behavior of a large cast of inmates and their guards, and the endless sessions of interrogation, which she found exhausting, but not physically brutal. When pressed by friends to denounce the prison for the rape and torture of the women detainees, on the grounds that such publicity might speed the battle toward democracy, she refused, saying that it was incorrect. What made the whole experience bearable, she writes, was the fact that the Burmese nature seems to include a large measure of calm, pride, dignity, and courage, and this feistiness and resilience color her fine book.

If the mood at Myanmar’s second literary festival was for the most part optimistic, the event was not without shadows. At the last minute, the government abruptly withdrew permission for it to take place, as planned, in the precinct of one of the city’s main pagodas and it had to be moved. A boycott by a number of Mandalay poets over the politics of the festival’s funding and a lingering distaste among some writers for association of any kind with participants known to have collaborated with the military regime lent a slightly sour note. The legacy of fifty years of repression is hard to shift.

Despite its resumption of relations with the West and the lifting of sanctions, the country is uneasy and uncertain. While efforts are underway to reform Burma’s education system, with support from Japan and the World Bank, and a bookseller from Yangon called Dr. Thant Thaw Kaung, together with his father U Thaw Kaung, a distinguished librarian, is busy setting up traveling libraries, literacy remains low. The young, long starved of literature, are turning more readily to “inspirational” self-help books, along with health and sports magazines, many of them from India, Korea, and China. The Internet, which reached Myanmar in a heavily censored fashion only in 2000, remains wayward. 51 percent of the population has no access to electricity. The economy is much indebted to Chinese investment, while the violent battles between the central government and the various ethnic minorities—said to constitute the longest-running civil war in the world—are far from being resolved.

Though many have fled to Pakistan, Bangladesh, and the Middle East, over a million Muslim Rohingya are still stateless, repressed, and subject to arbitrary imprisonment. An online novel written in 2012 by Muhammad Noor called The Exodus: A True Story from a Child of a Forgotten People is a tale of bullying, expulsion, and brutal treatment of the Rohingya, the persecution of his people having become, as he writes, a “pastime” for the Burmese. One of the loudest criticisms leveled against Aung San Suu Kyi, who is venerated by a large proportion of the electorate, is that she is failing to speaking out on behalf of the minorities.

Despite relatively free elections in 2008, the current constitution continues to guarantee considerable power to rich and well-armed military officers at every level, and there are widespread doubts about the degree to which they will be willing to relinquish it. For Aung San Suu Kyi to run in next year’s presidential election, the constitution will need to be changed, since her two sons have British citizenship, and all close family members of candidates must hold Burmese passports—a clause introduced, it appears, specifically to block her chances.

A new media law, ensuring freedom of speech and expression, is at draft stage, but until it reaches the statute books, the hated Printers and Publishers Registration Law could still make it possible to take writers into custody; there are moves to retain elements from it in the new laws that may curtail these freedoms. It is in this climate of hope but uncertainty that the writers are hard at work, committing to paper the rebellious thoughts stored away over the decades, hoping but not altogether trusting that they will still be at liberty to see them published. One writer at the festival spoke of being unable to shed the fear that one day, looking out of his window, he might see the dreaded blue car of the police coming to take him away. Those around him nodded vigorously.

-

*

Reviewed by Jonathan Mirsky, “Burma: The Despots and the Laughter,” NYRblog, July 24, 2013. ↩