Every spring, an old friend of mine named Xu Jue makes a trip to the Babaoshan cemetery in the western suburbs of Beijing to lay flowers on the tombs of her dead son and husband. She always plans her visit for April 5, which is the holiday of Pure Brightness, or Qingming. The traditional Chinese calendar has three festivals to honor the dead and Qingming is the most important—so important that in 2008 the government, which for decades had tried to suppress traditional religious practices, declared it a national holiday and gave people a day off to fulfill their obligations. Nowadays, Communist Party officials participate too; almost every year, they are shown on national television visiting the shrines of Communist martyrs or worshiping the mythic founder of the Chinese people, the Yellow Emperor, at a grandiose monument on the Yellow River.

But remembering can raise unpleasant questions. A few days before Xu Jue’s planned visit, two police officers come by her house to tell her that they will do her a special favor. They will escort her personally to the cemetery and help her sweep the tombs and lay the flowers. Their condition is that they won’t go on the emotive day of April 5. Instead, they’ll go a few days earlier. She knows she has no choice and accepts. Each year they cut a strange sight: an old lady arriving in a black sedan with four plainclothes police officers, who follow her to the tombstones of the dead men in her life.

Xu Jue’s son was shot dead by a soldier. Within a few weeks, her husband’s hair had turned white. Five years later he died. Qisile, she explained: angered to death. On her husband’s tombstone is a poem explaining what killed both men:

Let us offer a bouquet of fresh flowers

Eight calla lilies

Nine yellow chrysanthemums

Six white tulips

Four red roses

Eight-nine-six-four: June 4, 1989.

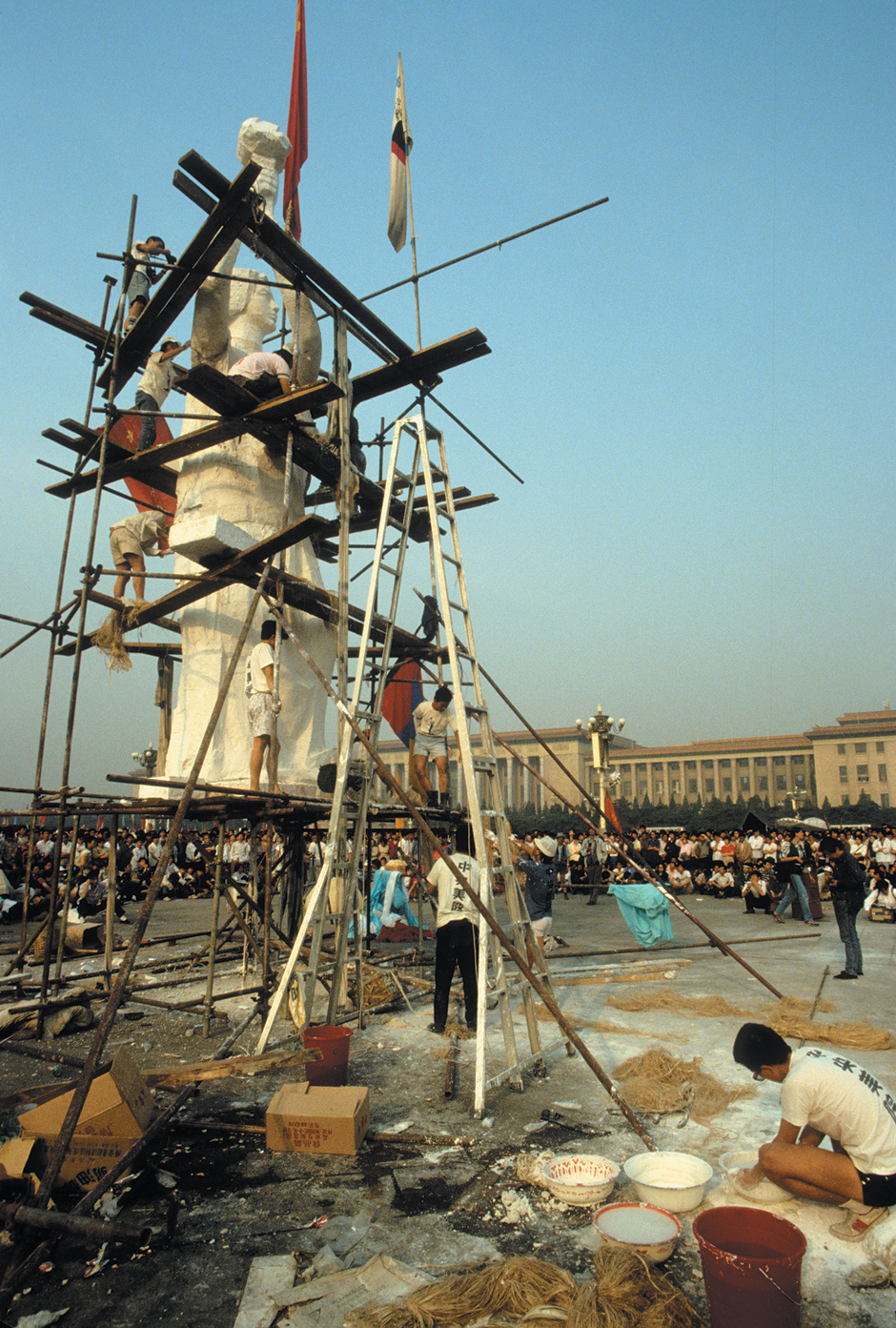

This is a date that the Communist Party has tried hard to expunge from public memory. On the night of June 3–4, China’s paramount ruler, Deng Xiaoping, and a group of senior leaders unleashed the People’s Liberation Army on Beijing. Ostensibly meant to clear Tiananmen Square of student protesters, it was actually a bloody show of force, a warning that the government would not tolerate outright opposition to its rule. By then, protests had spread to more than eighty cities across China, with many thousands of demonstrators calling for some sort of more open, democratic political system that would end the corruption, privilege, and brutality of Communist rule.1 The massacre in Beijing and government-led violence in many other cities were also a reminder that the Communist Party’s power grew out of the barrel of a gun. Over the coming decades the Chinese economy grew at a remarkable rate, bringing real prosperity and better lives to hundreds of millions. But behind it was this stick, the message that the government was prepared to massacre parts of the population if they got out of line.

When I returned to China as a journalist in the early 1990s, the Tiananmen events had become a theater played out every spring. As the date approached, dissidents across China would be rounded up, security in Beijing doubled, and censorship tightened. It was one of the many sensitive dates on the Communist calendar, quasi-taboo days that reflected a primal fear by the bureaucracy running the country. It was as if June 4, or liu si (six-four) in Chinese, had become a new Qingming, but one the government was embarrassed to admit existed. Now the crackdowns in May and June have lessened in intensity but are still part of daily life for hundreds of people throughout China, such as Xu Jue, the mother of a Tiananmen victim.

What remains? The author Christa Wolf used this phrase as the title of a novella set in late-1970s East Berlin. A woman notices that she is under surveillance and tries to imprint one day of her life in her memory so she can recall it sometime in the future when things can be discussed more freely. It is a story of intimidation and suppressed longing. Is this the right way to think of Tiananmen, as an act frozen in time, awaiting its true recognition and denouement in some vague future?

Two new books tackle the Tiananmen events from this vantage point. One is set in China and is about repressing memory; the other is set abroad and is about keeping it alive. They agree that June 4 was a watershed in contemporary Chinese history, a turning point that ended the idealism and experimentation of the 1980s, and led to the hypercapitalist and hypersensitive China of today.

Advertisement

Neither of the two books claims to be a definitive account of the massacre, or the events leading to it. That history is recounted in Timothy Brook’s Quelling the People: The Military Suppression of the Beijing Democracy Movement, a work by a classically trained historian who turned his powers of analysis and fact-digging on the massacre.2 Even though Brook’s book doesn’t include some important works published in the 2000s (especially the memoirs of then Party secretary Zhao Ziyang3 and a compilation of leaked documents known as The Tiananmen Papers), Quelling the People remains the best one-volume history of the events in Beijing. His closing remarks sum up much of what has been subsequently written:

The original events slip deeper and deeper into a forgetfulness into which many, foreigners and Chinese alike, would like to see them disappear, as a new and more profitable relationship to the world economy disciplines the next generation away from worrying about civil rights.4

The two new books take place during this post-Tiananmen era, investigating how Tiananmen has come to shape Chinese society, and how it affected some of its principal participants in exile.

Louisa Lim’s The People’s Republic of Amnesia is brilliantly titled, showing how much of what we take for granted in China today is due to efforts to forget or overcome the massacre. The book is a series of profiles of people who were involved in Tiananmen or were affected by it, some of which appeared as features on National Public Radio, for which she worked as a correspondent in Beijing for several years. This episodic structure has some drawbacks, primarily an absence of a complete background section early on about the massacre—what led up to it, how and why it happened.

But Lim helpfully starts out with a chapter called “Soldier,” which lays out the mechanics of the killing, as told from the perspective of a People’s Liberation Army grunt whose unit was ordered to clear the square. It’s well known that the army bungled clearing the square, first massing troops on the outskirts of town, then only halfheartedly trying to enter Beijing on successive days as crowds of people pleaded with and cajoled the young soldiers not to listen to their commissars’ propaganda and to go back to their barracks. Finally, when the troops were given clear orders to move, they inflicted horrific civilian casualties, which one can interpret—depending on one’s standpoint—as a result of the soldiers’ poor training, their superiors’ crude tactics, or as a deliberate attempt to pacify through terror.

Lim brings these broad-brush conclusions to life through her character, a befuddled, brainwashed young man whose unit had to be smuggled into town in transports disguised to look like public buses, while others came in by subway. It was the only way to get his unit past the civilian roadblocks and to spirit the soldiers and weapons into the Great Hall of the People, one of the principal buildings on the square that they used as a launchpad for their assault. In the days following the killing, we learn something even more surprising—how quickly ordinary people began siding with the soldiers, at least in public:

He did not believe this about-face was motivated by fear, but rather by a deep-seated desire—a necessity even—to side with the victors, no matter the cost: “It’s a survival mechanism that people in China have evolved after living under this system for a long time. In order to exist, everything is about following orders from above.”

The book continues with other chapters built around portraits of many different figures. We meet a student leader turned businessman, a contemporary student curious but cautious about the past, a reformist official under permanent government surveillance, a former student leader in exile, a mother of a dead student, and a nationalistic youth. Each helps Lim to make broader points about how costly forgetting is for a person, and for a society.

In her chapter on the former official, Bao Tong, Lim also makes use of newly published memoirs to question central tenets of how we understand the internal political machinations that led to the massacre. Until now, most observers have assumed that the students caused a split in the leadership, with Deng siding with hard-liners against Zhao, the reformist Party secretary who had some sympathy for the students. This was also Bao’s view until he read the memoirs of then premier Li Peng, himself a hard-liner, who argued that Deng had become frustrated with Zhao’s liberal tendencies much earlier. It’s hard to know if this interpretation is correct, but Lim is right to highlight it, showing how Zhao had been doomed from the start:

Advertisement

“This had nothing to do with the students,” Bao told me. He believes that Deng used the students as a tool to oust his designated successor. “He had to find a reason. The more the students pushed, the more of a reason Deng Xiaoping had. If the students all went home, then Deng Xiaoping wouldn’t have had a reason.”

This raises the question, much discussed over the past quarter-century, of whether the students could have avoided the massacre by dispersing a few days earlier when the military action seemed inevitable. In reviewing the material, however, one gets the feeling that not only Zhao’s fall but the massacre itself was almost inevitable. Deng had consistently opposed any political dissent and he seemed determined to send a message once and for all that outright opposition would not be tolerated.

Lim’s larger concern, however, is with how Tiananmen plays out in society today. Time and again, she demonstrates how little people under forty know about Tiananmen. In one chapter, the activist turned businessman finds that there is no point bringing up Tiananmen with his younger wife. “The reason they do not like to talk about 1989 is not because it is a politically sensitive topic or because it makes them uncomfortable. It simply does not register.”

This point is even more forcefully made in a chapter on a mainland Chinese student Lim met at an exhibition on the massacre in Hong Kong (where a museum devoted to it has just opened). She found the young man, named “Feel” because he had a feel for the English language, engaged and excited to learn more. But when she later visits him on his campus back in China, he is subdued and careful, learning as little as possible about what happened and conforming to the social norms prescribing that it be ignored. Lim explains the pervasive lying and mistrust among young people by quoting a statement by China’s Nobel Peace Prize laureate Liu Xiaobo that China had entered an age “in which people no longer believe in anything and in which their words do not match their actions, as they say one thing and mean another.”

One of Lim’s most important points is that Tiananmen made violence acceptable in today’s reform era. After the violence of the Mao era, people had hoped that social controversies wouldn’t be solved by force—that there would be no more Red Guards ransacking homes of real and imagined enemies, or mass use of labor camps. And while many of these more drastic forms of violence have been curbed, the Party regularly uses force against its opponents, illegally searching and detaining critics. Street protests haven’t ended. Although the state talks continually of social harmony and reportedly spends more on “stability maintenance” than on its armed forces, China is beset by tens of thousands of small-scale protests each year, “little Tiananmens,” as Bao tells her. Some are innocuous protests by retired workers seeking pensions, but others are by people trying to defend their homes from being taken away, and they are punished by violent attacks by government thugs or by lynchings carried out by the notorious chengguan street police.

Lim tells her stories briskly and clearly. She moves nimbly between the individuals’ narratives and broader reflections, interspersing both with short, poignant vignettes, such as the artist who had cut off part of his finger to protest the massacre but now doesn’t feel he can tell his twelve-year-old son why. Clearly Lim has thought and cared a lot about the Tiananmen events, and she is taking a great risk in writing this book; if history is any guide, the book could make it difficult for her to return to China, where the government has a blacklist of academics and journalists whose works have touched on sensitive subjects. This makes her book courageous, probing one of the Communist Party’s sorest wounds.

Lim’s final chapter is one of the most worthwhile, but also suggests some of the problems of her book. Instead of a profile, she recounts the crackdown on protesters in Chengdu, a large southwestern city and China’s second-most-important center of intellectual life. Lim dug up State Department cables and interviewed eyewitnesses who described the extremely violent suppression of the protests there. It is a frightening chapter, written with verve.

At times, however, Lim is a bit too breathless in describing the novelty of her findings. Other writers have made the broader point that what happened in 1989 was a nationwide movement, especially in The Pro-Democracy Protests in China: Reports from the Provinces (1991), edited by Jonathan Unger. As for the events in Chengdu, Chinese authors have discussed them, especially the writer Liao Yiwu.5 Lim is to be commended for recounting the events in a more complete form, and for finding so much new information. But the fact that outsiders often reduce June 4 to a Beijing story mainly reflects the fact that the nationwide events of 1989 still haven’t received full-scale treatment in a single volume. This probably says more about the myopia and fragmentation of modern academic studies than it does about Lim’s main theme of amnesia.

Rowena Xiaoqing He also moves the picture beyond Beijing in her moving and very personal account of life as a political emigrant, Tiananmen Exiles: Voices of the Struggle for Democracy in China.6 Now a teacher of a popular undergraduate course on Tiananmen at Harvard, He was a high school student during the protests. Still, she was a passionate participant in the demonstrations in her southern Chinese hometown of Guangzhou, joining protests despite her parents’ misgivings. After the protests were crushed there, she dutifully memorized the government’s propaganda so she could pass her university entrance exams, graduate, and eventually land a good job during the start of China’s economic boom.

In her heart, however, she couldn’t forget the protests. Eventually, she surprised family and friends by quitting her job to get a graduate degree in Canada. She chose education as her field of study, thinking that it was central to avoiding another Tiananmen. She also began an oral history of the uprising.

Her book is written in the tradition of contemporary academic narrative research, which invites her to tell her own story as a way of making clear her standpoint. We learn of her upbringing during the Cultural Revolution, the problems her family faced, and how her father’s idealism was crushed during the Mao period. She spends time with her mother in an opera troupe, and is shuttled between city and countryside as her parents struggle to adapt to that era’s political winds. All of this helps us understand the sense of entrapment that the Tiananmen generation felt growing up during the Mao era, and the resulting desire to break out and embrace the 1989 movement.

He’s own story is balanced by three other stories of better-known participants: the student leaders Yi Danxuan, Shen Tong, and Wang Dan. Her questions and answers are interspersed with parenthetical notes that explain her interlocutors’ answers, silences, and moods.

Although the stories of Shen and Wang are fairly well known, He’s gently probing questions and psychological insights help us understand the sometimes egotistical idealism of these people, who plunged into the student movement despite entreaties by their parents not to get involved. As Yi puts it to her:

My friends and I never thought that the government would order the army to open fire although early on my father had said that would happen. This showed that we didn’t understand the nature of the regime well.

The people He writes about can be considered failures. Their battle lost, they were forced to live abroad, where they remain in a permanent state of mistrust and unease—little wonder considering that state authorities continue to try to hack their computers and follow their movements. Even if they constructed workable lives for themselves in business or academics, as He puts it, Tiananmen is,

in many ways, a continuing tragedy because the victims are no longer considered victims and the perpetrators no longer perpetrators. Rather, the latter have become the winners against the backdrop of a “rising China.”

But He has deeper concerns than keeping score. Instead, she is trying to figure out what happens when something one loves is extinguished. Does it really die or does it continue on in other forms? Is the exiles’ memory less valid than the reality of a political and economic oligarchy that has obliterated the idealism of an earlier generation? Which vision has more staying power?

For me, research is an experience in space and time, a connection between here and there, between the past and the future, with us living in the present, trying to make old dreams come true. The roots are always there, but our dreams may die. I hope this project will keep the dreams alive—not only my own but also those of others.

At times, He’s book is wildly romantic and too heavily focused on the experience of students to be representative of the entire movement—thousands of workers also participated, and are hardly mentioned. But I found it a convincing and powerful account of a central experience in contemporary Chinese life. One shouldn’t forget that, because of Tiananmen, some of China’s greatest public intellectuals of the late twentieth century died in exile. Fang Lizhi, Liu Binyan, and Wang Ruowang are among the most prominent (Fang and Liu contributed to The New York Review).

In this, China’s exile movement parallels the great émigré communities in Europe during the twentieth century: the Poles in London, the Russians in Paris, the subterfuge and mistrust of Eastern European and Soviet ethnic minorities in cold war Munich. They were sometimes ridiculed and reduced to backdrops in spy novels, but they also had their dignity and an ultimate triumph, even if for the most part they did not become well known in their home countries after the fall of the Iron Curtain.

Living in today’s China, one realizes that amnesia is pervasive and exile all too common, but so too is the idea that the Tiananmen events still have meaning—that they continue to have a presence, not only in the negative sense of causing repression and censorship, but in more positive ways too. I was reminded of the New York Times correspondents Nicholas Kristof and Sheryl WuDunn, who titled their 1990s best-selling book about that era China Wakes. Today, such a book would probably be about GDP, peasant migration, and aircraft carriers, but their genius was to include Tiananmen too, not merely as a background to economic growth—including the theory of the economic takeoff as, in effect, compensation for political repression—but as part of a broader awakening among the Chinese people, even if the political aspects of that awakening have been eclipsed by the economic development of the past quarter-century.

If this sounds naive, consider that almost exactly a decade after Tiananmen, ten thousand protesters quietly surrounded the Communist Party’s Zhongnanhai leadership compound in Beijing, asking that their spiritual practice, Falun Gong, be legalized. Had they missed the government’s brutal message, or were they on some subconscious level emboldened by a rising consciousness among ordinary people—a sense that they had rights too?

The Falun Gong protesters met with intense repression, including torture, and most people are now more circumspect in pushing for change. But in talking to intellectuals, activists, teachers, pastors, preachers, and environmentalists over the past years, I’ve found that almost all say that Tiananmen was a defining point in their lives, a moment when they woke up and realized that society should be improved. It can’t be a coincidence, for example, that many major Protestant leaders in China talk of Tiananmen in these terms, or that thousands of former students—not the famous leaders in exile or in prison, but the ones who filled the squares and streets of Chinese cities twenty-five years ago—are quietly working for legal rights and advocating environmental causes.

It’s true that many of these people are at least forty years old, and one can rightly wonder, as Lim does, about the upcoming generation, for whom idealism might seem childish or irrelevant. But idealists are a minority in any society. Cynicism and materialism are of much concern, but Chinese people themselves—including young people—discuss their presence and their danger in person or online every day.

Equally telling is a widespread yearning for something else—a search for values and a deeper meaning to life. Some Chinese find this in religious life, hence the ongoing boom in organized religion. But many are active in other ways, too. Some are resuscitating and recreating traditions, or engaging with the age-old Chinese question of how to live not just an ordinary life of labor, marriage, and family, but a moral life. It would be simplistic to trace this concern solely to Tiananmen, but some of this humanistic impulse surely is rooted in that era’s unbounded idealism. Perhaps this is another, less didactic way of looking at Tiananmen: as a sacrifice, unwitting and unwanted, that helped define a new era.

This certainly is how He sees it. After the massacre, she went back to high school, defiantly wearing a black armband of memory for the dead. Her teachers made her remove it, and she cried bitterly, thinking the dream was over:

When I was forced to remove my black armband in 1989, I thought that would be the end of it. Bodies had been crushed, lives destroyed, voices silenced. They had guns, jails, and propaganda machines. We had nothing. Yet somehow it was on that June 4 that the seeds of democracy were planted in my heart, and the longing for freedom and human rights nourished. So it was not an ending after all, but another beginning.

-

1

The number of cities involved in protests was highlighted in an exhibition after the massacre in Beijing’s Military History Museum and cited by James Miles in The Legacy of Tiananmen: China in Disarray (University of Michigan Press, 1996). ↩

-

2

One should also note the works of Wu Renhua, a Tiananmen participant and author of two Chinese-language works, as well as a forthcoming book by Jeremy Brown of Simon Fraser University. Thanks to Perry Link for pointing these out. ↩

-

3

Reviewed in these pages by Jonathan Mirsky, July 2, 2009. ↩

-

4

Stanford University Press, 1998, p. 218. The book was originally published in 1992. The 1998 edition adds an afterword from which this was cited. ↩

-

5

For a Song and a Hundred Songs: A Poet’s Journey Through a Chinese Prison (Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2013), reviewed in these pages by Perry Link, October 24, 2013. ↩

-

6

For a version of Perry Link’s introductory essay to the book, see “China After Tiananmen: Money, Yes; Ideas, No,” NYRblog, March 31, 2014. ↩