If, at the end of 1953, you’d asked almost anybody in Britain what had been the year’s most significant national events, it wouldn’t have been hard to predict their replies: the Queen’s coronation and a British team conquering Everest. (Never mind that the two men who made it to the top were from New Zealand and Nepal.) Yet when it comes to Britain’s global reach ever since, a better answer—if unimaginable at the time—might have been the publication of a novel written by a forty-three-year-old bachelor to take his mind off “the agony” of getting married; a novel, moreover, that the publisher Jonathan Cape thought was “not up to scratch,” but accepted anyway as a favor to the author’s brother, the Cape travel writer Peter Fleming. It began: “The scent and smoke and sweat of a casino are nauseating at three in the morning.”

The book was, of course, Casino Royale, starring a man named for the author of Guide to the Birds of the West Indies, which Ian Fleming had in the Jamaican house where he wrote it. He chose the name, he later explained, because he wanted something plain-sounding and James Bond was “the dullest name I’ve ever heard.”

Casino Royale soon became a best seller in Britain, where the reasons for its appeal—and that of its annual successors—aren’t difficult to imagine. At a time when food was still rationed and not many people had cars, fridges, or the chance for foreign travel, here was a man who drove his 4½-liter Bentley through France airily ordering the Blanc de Blanc Brut 1943 to accompany his caviar. (In those far-off days, readers might also have enjoyed the phrase “Bond…lit his seventieth cigarette of the day.”) And the political message was reassuring too. Britain’s world-power status may be fading. It may even need the occasional injection of American cash—in Casino Royale Felix Leiter of the CIA

1 helps Bond out with an envelope marked “Marshall Aid…With the compliments of the USA.” Nevertheless, a little thing called British pluck meant that the old place could still save the world when required.

Bond was initially less successful in the United States, a country that the books regard with reluctant admiration and less ambivalent condescension. Visiting New York in Live and Let Die, Bond is reminded to “say ‘cab’ instead of ‘taxi’ and (this from Leiter) to avoid words of more than two syllables.” In Diamonds Are Forever, he kindly allows that “America’s a civilized country. More or less.”

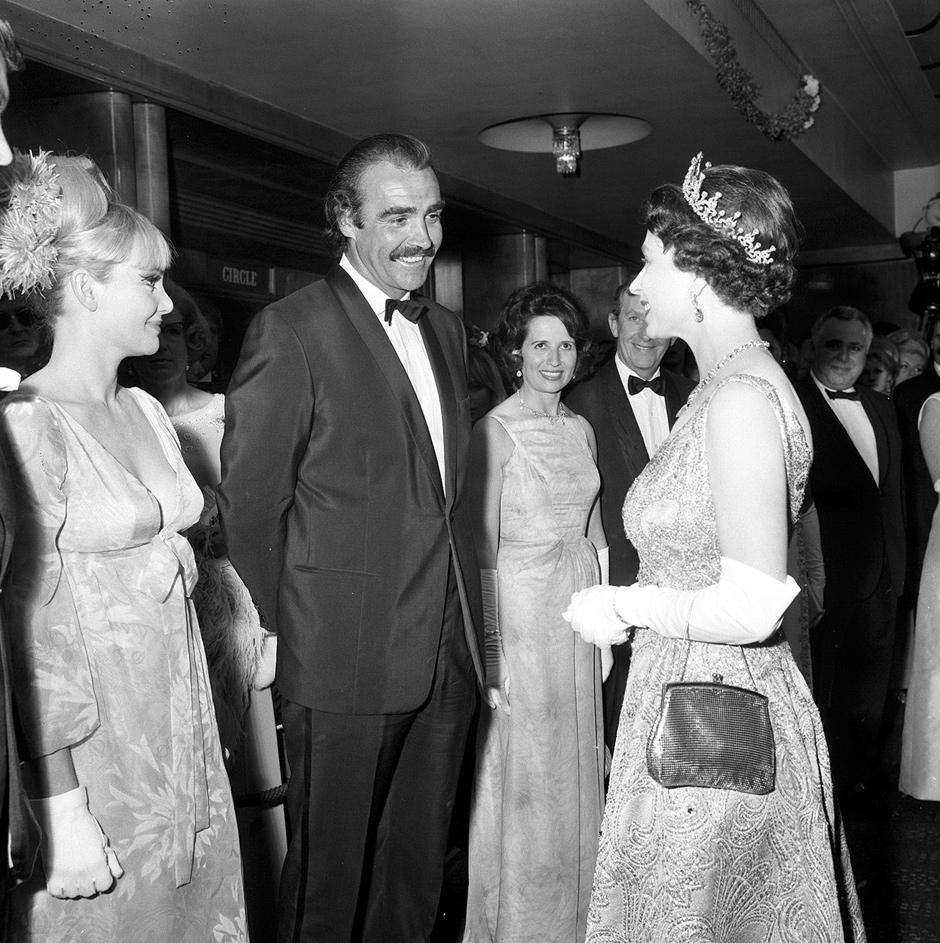

But in March 1961 came a sudden breakthrough, when President Kennedy named Fleming’s From Russia with Love as one of his ten favorite books in Life magazine.2 By the end of the year, Fleming was the biggest-selling thriller writer in America. This, in turn, ensured there was an audience for the first Bond film, Dr. No, in 1962—and since then the man has never really looked back. In his rather sniffy commemoration of forty years of the Bond movies in 2002, even Anthony Lane was forced to concede that “our world is dominated by James Bond as by no other fictional character.” Ten years later, when the opening ceremony of the London Olympics celebrated Britain’s contributions to the world from Shakespeare onward, Bond was not just featured but comprehensively stole the show by getting the Queen to jump out of a helicopter with him.

Meanwhile, the books have kept coming too. Although Fleming wrote only twelve Bond novels and two short-story collections, William Boyd’s Solo is the thirty-eighth to be published—and that doesn’t include either film novelizations or Charlie Higson’s Young Bond series, with the teenage James besting the baddies in his boarding school days. Indeed, in recent times, the “continuation Bonds” have become more prestigious, and more hyped, than ever. In 2008, Sebastian Faulks, who started the trend for respected British literary novelists to follow in Fleming’s footsteps with Devil May Care, had to be content with a catsuited model bringing the first copies of the novel up the Thames in a speedboat while helicopters circled overhead. Solo was launched at London’s Dorchester Hotel with seven Jensen Interceptor sports cars picking up signed copies and whisking them in Perspex briefcases to the airport where, strapped into the cockpit, they were flown to seven cities on four continents.

Yet while it can’t be denied that Bond has achieved a level of global dominance that Ernst Blofeld might have envied, one surprisingly basic question has never gone away: Are the original novels any good? It’s a question that even Ian Fleming appeared unsure about. At times, his self-deprecation sounds alarmingly close to self-loathing: “I have a rule of never looking back. Otherwise I’d wonder, ‘How could I write such piffle?’” At others, it seems more like an understandable defensiveness provoked by his critics, many from the intellectual and literary circles in which he moved. One of them was his wife Ann, who declined to have Casino Royale dedicated to her, and once wrote to her friend Evelyn Waugh, “I love scratching away with my paintbrush while Ian hammers out pornography next door.” There is a distinct note of sadness in a 1956 letter from Fleming to Raymond Chandler about how “I…meekly accept having my head ragged off about [my books] in the family circle.”

Advertisement

This internal conflict is particularly acute—albeit urbanely expressed—in Fleming’s 1962 essay “How to Write a Thriller.” After some standard self-abasement about his lack of artistic credentials and how, rather than aiming for the reader’s head or heart, the target of his books is “somewhere between the solar plexus and well, the upper thigh,” an unmistakable sense of professional pride creeps in. Though his plots are, he admits, “fantastic,” “the constant use of familiar household names and objects…reassure[s the reader] that he and the writer have still got their feet on the ground.”

And it’s precisely this balance between realism and fantasy that’s central to the most full-throatedly convincing defense of Fleming, Kingsley Amis’s The James Bond Dossier (1965). Admittedly, one of Amis’s motives was to bid a typically belligerent farewell to academic life by championing books that were the object of high-brow scorn. Even so, he rarely defends the indefensible: lamenting, among other things, the transcription of Harlem speech in Live and Let Die; the fight between two gypsy women in From Russia with Love that ends with blood trickling down their naked breasts; and the odd moments of straightforward bad writing. He does, however, speak up defiantly for wish fulfillment (“a common and normal human activity”); for escapist literature in general (“I like reading about you and me as much as the next man does, but not all the time”); and for the many scenes where the villain explains his plot to Bond shortly before expecting to kill him as “one of those conventions which repays our tolerance”—on the indisputable grounds that we wouldn’t “want to miss any of that.”

Nonetheless, where the book makes its strongest case is in its careful attention to how well both the realism and the fantasy are done individually, and how cunningly they’re combined. For Amis, there’s far more to Fleming’s “scaffolding of the plausible” than just those familiar household names. The sheer range of Bond’s skills, for instance, may be extravagant—but, taken one by one, none is unbelievable.3 Amis also points out that while Bond’s generalizations about women are “not respectful,” he treats the ones he meets with affection and warmth. (In fact, and this is a genuine shock when you return to the books, Bond is instantly and deeply smitten with almost every one of his improbably named beauties—often to the point of contemplating or proposing marriage.)

As for the fantasy element, that goes far beyond the merely exciting and deep into the realms of myth, especially with all those misshapen villains, whose tortures have the quality of nightmare: “The horror that has been designed for you alone.” Indeed, when he reaches the particularly unsettling case of Blofeld’s deadly Japanese garden in You Only Live Twice, Amis can’t prevent his bluff, nonacademic mask from briefly slipping. This, he persuasively suggests, is an example of Fleming’s “neo-Coleridgean ability to domesticate the marvelous.”

All of which poses more problems for those entrusted with Bond’s post-Fleming adventures than you (or they) might expect. Amis’s own effort, Colonel Sun, published under the pseudonym Robert Markham in 1968, was the first—and remains one of the best. Inevitably respectful of Fleming’s style and methods, the book also restores the kind of hair-raising torture scene that Amis regretted Fleming’s having largely ditched following an influential 1958 attack on his sadism by the critic Paul Johnson. Partly for those reasons, though, the book has an air of calculation—and occasionally of literary commentary—that stops it from wholly catching fire. Meanwhile its publication, licensed by Fleming’s copyright holders Glidrose Publications, infuriated Ann Fleming, who complained to Evelyn Waugh that “though I do not admire ‘Bond’ he was Ian’s creation and should not be commercialized to this extent.” Her review of Colonel Sun for the London Sunday Telegraph was never printed for fear of libel.

Not until 1981—the year of Ann’s death—did the franchise resume, and for the next twenty-one years, and twenty books, it was placed in more unashamedly pulpy hands. John Gardner, who went on to write fourteen continuation Bonds, decided the way forward was “to put Bond to sleep where Fleming had left him in the sixties, waking him up…in the 80s having made sure he had not aged.” As a result, despite Gardner’s claims to be inspired by the 007 of the books rather than the films, his Bond ends up feeling like neither one thing nor the other—and therefore just another action hero influenced by James Bond instead of the real thing. In Fleming, Bond’s murder count works out at a modest three per novel. In Gardner, he blasts away like Rambo. Then again, as Gardner later complained, he had to satisfy the often conflicting demands of Glidrose and of his publishers on both sides of the Atlantic: “a mightily strange way of…editing a book.”

Advertisement

Still, at least Gardner could write—unlike Raymond Benson, who followed him, and whose books contain such phrases as “Lady Luck could be a cruel mistress.” This time, Benson was instructed to stay in sync with the films, which means, for example, that Bond continues to slaughter henchmen by the truckload and that Felix Leiter’s limbs have grown back since that unfortunate incident with the shark in Fleming’s Live and Let Die. Even so, Benson managed six books before, in 2002, with sales falling, he too handed in his license and bravely proposed that “it would be a smart idea” for the next book to put Bond back in the cold war where he belongs.

And as it turned out, that’s what the next book did. Like Gardner, Sebastian Faulks announced his desire to return to Fleming’s Bond as he was before the movie world got hold of him. Unlike Gardner, he made a thoroughgoing attempt. Devil May Care—commissioned to commemorate the one-hundredth anniversary of Fleming’s birth—takes place in 1967, and equips Bond with a full set of Fleming-created memories, a distaste for gadgets, a leggy accomplice called Scarlett Papava, and an antagonist whom “an extremely rare congenital deformity” has provided with a monkey paw for a hand and who targets Britain with a passion that only the most important nations deserve. (As Amis put it, “Delusions of grandeur…go with delusions of persecution.”) When Felix Leiter shows up to help, he’s duly missing one and a half limbs. Devil May Care, whose author is described as “Sebastian Faulks writing as Ian Fleming,” does sometimes feel like a performance—but also like an inspired one.

Paradoxically, then, it seemed a retrograde step that Faulks’s successor Jeffery Deaver should return to the present day. In Carte Blanche, a nonsmoking, eco-friendly, gadget-loving Bond—with a bit of assistance from an able-bodied Felix—foils a spectacularly complicated plot based in South Africa. Overall, it’s a perfectly good thriller of the kind that made Deaver’s name. Yet not even the presence of a woman named Felicity Willing is enough to banish the Gardner/Benson sense that any action hero, by any other name, would have served Deaver just as well—except perhaps commercially.

And now comes William Boyd, another highly regarded British literary novelist determined, as he told The Guardian, “to get away from the films”—for the customary reason that

the Bond of the novels…is a far more interesting and complex character…. I want [Solo] to be a realistic novel. I didn’t want it to be fantastical…. I wanted him to have a real mission that wasn’t anything to do with some organization trying to rule the world or mountains filled with atom bombs.

It is an interview that explains the book’s many qualities—and the one thing it lacks.

Boyd establishes his methods in the first chapter, where Bond wakes up alone in the Dorchester Hotel in 1969 the morning after his forty-fifth birthday. After putting on his trusty blue worsted suit and enjoying the sort of breakfast that might fell a horse, he bumps into a woman wearing a “navy catsuit…that…revealed the full swell of her breasts” and introduces himself as “Bond, James Bond.” But he also keeps remembering an experience in France just after D-Day when he first faced imminent death—thereby giving us details of a wartime past that Fleming had mentioned only in passing.

This willingness to both defer to and extrapolate from the source material continues for the rest of the book, not least in its emphasis on Bond’s Scottishness. (Oddly, the most famous English spy is neither English nor, in any recognizable sense, a spy.) A Scot himself, Boyd obviously enjoys playing up this aspect of Bond, and again stressed in the Guardian interview that it was there in Fleming—although he didn’t add the significant detail that it was there only in the four books Fleming wrote after the Scottish actor Sean Connery had been cast in Dr. No.

Summoned to see M in the traditional way, Boyd’s Bond is soon given his mission. The African country of Zanzarim (resembling Nigeria) is in a state of civil war, with the southern region of Dahum (resembling Biafra), having declared independence after oil was discovered there. M wants him to stop the fighting so that Britain can enjoy Zanzari oil without any unpleasantness. And with that, 007 flies to the capital, meets the head of the British station—as luck would have it, a beautiful woman named Blessing—and after an almost Conradian journey south helps the Dahum forces to win an important battle. Except, of course, that his job is to make sure that they end up losing the war.

Boyd wrote the novel, he told The Guardian, “entirely in my own voice.” This doesn’t apply merely to the prose—which is sharper and more elegant (or, if you prefer, better) than Fleming’s—but also to the moral ambiguity. Such ambiguity is sometimes raised in the original novels, but not in a way that can be described as having much depth. The goodies may sometimes behave a little questionably, but the baddies are never other than unconditionally evil. Nor is there much doubt that British interests are those of civilized beings everywhere. In Solo, by contrast, the realpolitik isn’t far from the “anguished cynicism” of John le Carré that Amis found less sympathetic than Bond’s “belief, however unreflecting, in the rightness of [his] cause.”

But while purists might regard this as a betrayal, a case could certainly be made that it’s another justified extrapolation: a more considered treatment than Fleming could ever allow himself of issues that hover in the background of his novels. What should be clear by now, though, is the wrongness of Boyd’s idea that the Bond movies are responsible for introducing the fantasy elements that we associate with him. Organizations bent on world domination and island fortresses (if not mountains) full of atomic equipment (if not bombs) are already present in Fleming—along with women killed by being painted gold, groups of young hotties on top of the Alps being hypnotized into biological warfare, Blofeld stalking that murderous garden in full samurai uniform, and plenty more besides.

In other words, by ascribing the wilder reaches of Fleming’s gothic imagination to the film world, and so ignoring it, Boyd is not quite giving us the “real” Bond at all. His tidied-up version means that Solo has none of Fleming’s mad plot flaws and excesses, but disappearing along with them is something that lies close to the books’ heart: the mythical element identified by Amis—and by Fleming himself, who in 1960 told a radio interviewer that “I am sufficiently in love with the myth to write basically incredible stories with a straight face.”

There’s no denying that Solo is thoughtful and heartfelt, as well as entertaining. Yet in the end, one of its main achievements is to remind us of the irreducible strangeness of the original books—and so confirm the truth of Kingsley Amis’s closing words in The James Bond Dossier. “Ian Fleming,” Amis concluded with a flourish, “leaves no heirs.”

-

1

An organization, incidentally, that Fleming played a part in founding as a wartime naval intelligence officer. ↩

-

2

Fleming later returned the compliment in The Man with the Golden Gun, where Bond settles down with three fingers of bourbon and a copy of Profiles in Courage. ↩

-

3

Although Amis’s point that Bond’s daily alcohol intake of half a bottle of spirits is “another instance of Mr Fleming’s policy of moderation about Bond’s attributes” may be more autobiographical than he intended. ↩