1.

The last time that the National Gallery devoted an exhibition to Andrew Wyeth, it was billed as a revelation but received with some resistance. This was the notorious Helga show, or striptease, as John Updike—one of the few critics to find things to admire in the 1987 exhibition—described it: several hundred pictures executed on the sly (both Wyeth’s wife and Helga’s husband were, reportedly, kept in the dark) from 1971 to 1985, representing a striking German woman with long, reddish-blond hair, often depicted, clothed or in the nude, in pensive reverie. Helga Testorf, a GI bride and homesick mother of four, served as a nurse in the household of Karl Kuerner, a machine gunner for the German army during World War I, and was a neighbor of the Wyeths at Chadds Ford, in the Revolutionary War district of the Brandywine Valley in southeastern Pennsylvania, an area dotted with picturesque farms and the secluded mansions of the du Ponts.

It wasn’t just the voyeuristic aura of the Helga exhibition, the museum’s first one-man show granted to a living American painter, that annoyed critics and—according to Neil Harris’s recent book about its longtime director J. Carter Brown—troubled curators as well.1 It was its seemingly meretricious nature, at a time when Wyeth’s popularity with museumgoers remained high even as his reputation among critics, having crested by the mid-1960s, was in decline.

The pictures on the walls belonged to a rich Philadelphia publisher who, as owner of the copyrights, stood to gain from exposure in such a respected venue. After a national tour of the exhibition, he crassly sold his cache to a Japanese company. Lambasted by critics as an “absurd error” (John Russell) and an “essentially tasteless endeavor” (Jack Flam), the show was a traumatic event for the museum, “the most polarizing National Gallery exhibition of the late 1980s,” according to Harris.

The absorbing new Wyeth exhibition, “Andrew Wyeth: Looking Out, Looking In,” is in certain respects the opposite of the Helga show, even something of an exorcism of it. Where the Helga show was dominated by a single human figure, the current exhibition is entirely without people, except for a couple of preparatory sketches. Insistent images of Helga confronted viewers of the earlier show: Helga radiantly nude except for a choker, à la Olympia, against black velvet; Helga reclining naked under menacing meat hooks (“like the ones from which Hitler had von Stauffenberg hung by the neck,” commented John Russell); Helga in blackface, or rather black skin, in the unsettling slave fantasy called Barracoon. (Wyeth remarked that he was “thinking of the enclosures in which they kept slaves in the time of Thomas Jefferson…. To me,” he added artlessly, “this is purity, simplicity.”) Instead of such cacophonous material, the current show is built around a single, quiet motif in many variations: the window.

The result of the carefully conceived installation, in which preparatory studies are grouped around more finished and often drastically simplified (in Wyeth’s phrase, “boiling down”) paintings, is an increasingly immersive experience, an aesthetic revelation rather than a prurient one. The catalog essays, by National Gallery curators Nancy Anderson (on Wyeth’s working process) and Charles Brock (comparing Wyeth’s windows to two influences, Edward Hopper and the Pennsylvania precisionist Charles Sheeler), are understated, inquisitive, and well written—in English that, as Marianne Moore once said, cats and dogs can understand.

Meanwhile, there are signs that the tacit embargo on scholarly attention to Wyeth—what Wanda Corn calls the “Wyeth Curse” that “has muzzled research and intellectual dialogue in the academy”—is being lifted after some fifty years. One reason, surely, is that Wyeth, whom Robert Hughes judged, in 1982, “the most famous artist in America” (“because his work,” according to Hughes, “suggests a frugal, bare-bones rectitude, glazed by nostalgia but incarnated in real objects”2), has all but disappeared from view in popular culture, eclipsed by Andy Warhol and Georgia O’Keeffe, and his work is open to new discovery.

A younger generation of art historians, immune to the old battles surrounding Wyeth, when he was often regarded as the crusty counterpoise of anything truly modern in art, is exploring his varied work—more overlooked than truly looked at in recent decades—as though it is virgin territory. Wyeth’s surging reputation in Asia—many of the pieces in the current show are borrowed from a single collection in Japan, while interest in Wyeth (referred to as “Wyethiana”) among Chinese artists has intensified since the end of the Cultural Revolution—is another reason why he is back in circulation.

2.

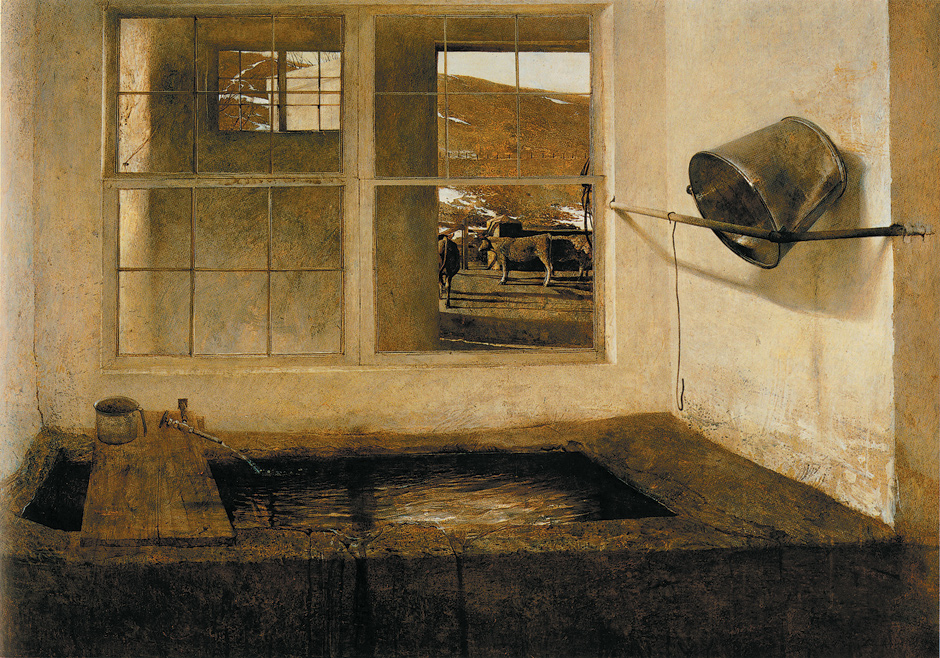

“Andrew Wyeth: Looking Out, Looking In” was inspired by a gift to the National Gallery in 2009, a few weeks after Wyeth’s death at age ninety-one, of a relatively small—one might even say window-sized—painting called Wind from the Sea, begun in the Wyeths’ summer retreat in Cushing, Maine, in August 1947, when Wyeth was barely thirty, and two years after his father, N.C. Wyeth, the great illustrator of Treasure Island and The Last of the Mohicans, died, along with Wyeth’s four-year-old nephew, in a railroad accident at Chadds Ford. His father’s death was particularly momentous for Wyeth, the youngest of five children, and haunted many of his subsequent paintings, such as the superb and enigmatic Spring Fed (1967), a centerpiece of the National Gallery show, with its brace of windows (one of which is mysteriously shorn of its mullions) looking out from a cistern in the Kuerner barn on a field near the crossing where N.C. died.

Advertisement

Homeschooled as a frail child and free to roam the idyllic Brandywine countryside in dress-up games of Robin Hood—the picture of Robin’s death by his father was, according to Wyeth, an influence on the horizontal layout and “sense of foreboding” of Spring Fed—Wyeth, whose only art teacher was his father, had shown early promise, and doggedly completed the tedious drawing exercises of cones and boxes that his father inflicted on him. The elder Wyeth, who had built at Chadd’s Ford an imposing house and studio—with a separate high-ceilinged room, equipped with movable stairs, for painting murals—created around him a theatrical grandeur that overshadowed and overwhelmed his gifted son, who preferred to work for much of his life in a small converted schoolhouse nearby. To visit the two studios today, now in the possession of the Brandywine Conservancy, which also administers the Brandywine River Museum with its trove of art by the Wyeths, is to step from the fantasy-driven dimensions of the Gilded Age to something more intimate and human-scale, in keeping with Wyeth’s own subtler artistic practice.

Wyeth developed early on a flair for watercolor, combining a freehanded vigor with an uncanny ability to capture detailed effects of water and light in pictures that recalled Winslow Homer, a family idol—the Wyeth summer home in Maine was called “Eight Bells” after Homer’s heroic painting of sailors taking their bearings at sea. In 1937, when he was twenty, Wyeth’s precocious show of watercolors—“the very best watercolors I ever saw!” according to N.C.—sold out in two days at the prestigious Macbeth Gallery in New York.

But Wyeth sensed that something more than facility and commercial viability were needed, an attitude reinforced by his young wife, Betsy, who had grown up in the Roycroft community in upstate New York, dedicated to the austere arts-and-crafts values of John Ruskin and William Morris. When Wyeth painted a cover for The Saturday Evening Post in 1943 and was offered a contract for ten more, Betsy, his longtime business manager, warned him against it: “You will be nothing but Norman Rockwell for the rest of your life. If you do it, I’m going to walk out of this house.” His father’s death, according to Wyeth, “put me in touch with something beyond me, things to think and feel, things that meant everything to me.”

Wind from the Sea was among the first paintings in which he tried to express some of those things. A partially opened window, with billowing curtains decorated with crocheted birds momentarily in flight, almost fills the frame, revealing—through the frayed and disintegrating lace—a view of a field traversed by a curving dirt road, a narrow line of evergreens on the horizon, and a silvery sliver of the sea. The mood of this monochromatic painting, all grayish greens giving way to greenish grays, is timeworn and melancholy, even if we don’t know that among the distant evergreens is a family graveyard, the same one in which Wyeth himself is now buried.

The picture was executed on a panel of Masonite in the exacting medium of egg tempera, requiring many applications over weeks or even months of patient crosshatching. Paradoxically, the result, viewed up close, is a glossy painted surface in which marks of the hand are rendered all but invisible, like a photographic print of itself.

In sharp contrast are the freely rendered studies, in pencil and watercolor, that, as was Wyeth’s usual practice, preceded the laborious painting. According to Wyeth, he was working in a stifling upper room of the dilapidated, eighteenth-century farmhouse belonging to his friends the destitute siblings Christina and Alvaro Olson, who made a hardscrabble living by picking blueberries, when he crossed the room to open a window and let in some air.

It is at this point that the full drama of Wind from the Sea begins to emerge, for the picture is intimately tied to Christina’s World, painted the following year in 1948, and may even be viewed as something of a preview of it. Christina’s World is among the most immediately recognizable pictures in all of American art, as familiar as Whistler’s Mother or Grant Wood’s American Gothic. It hangs in the Museum of Modern Art, as isolated in its resolute pictorial strangeness, among the surrounding expanse of cubist and abstract art, as the lone figure of Christina Olson herself crawling—or rather clawing—her way across the same Maine field that we see out the window in Wind from the Sea, toward the same distant farmhouse in which Wyeth opened the window to let in some air.

Advertisement

Much has been written about how the paraplegic Christina, crippled by a childhood disease that may have been polio, was unable to walk, and how her close friend Betsy James, another summer visitor, introduced Wyeth, her future husband, to Christina, already past fifty at the time of the painting. Betsy James actually posed for Christina’s body. But the linkage between the two paintings may be closer still. For we learn from this exhibition that Wyeth’s first quick sketch of the curtains billowing from the opened window was on a piece of paper that already had Christina’s head carefully drawn on it. Wyeth positioned the window immediately beneath the head, as though Christina was somehow wearing the window or had partially turned into it. According to the curators, Wyeth simply “grabbed” a piece of paper close to hand, but it seems possible that more is going on here than mere convenience.

For if we place Christina’s World and Wind from the Sea side by side, we notice something strange. The two paintings are structured in remarkably similar ways, with the billowing curtains reproducing, and at the same angle, the swell of what Randall Griffin, in an article about Wyeth’s idealization of Christina’s “abnormal” body, refers to as “the figure’s attractive, well-defined derriere.” This evocation of a ghostly female presence would help explain why window and head are conjoined in the initial sketch, and why Wyeth referred to Wind from the Sea as a portrait of Christina.

3.

Robert Frost first saw Wind from the Sea in the living room of its owner, Charles Morgan, founding director of the Mead Art Museum at Amherst College, where both men taught. A classical archaeologist with wide-ranging tastes—he wrote a pioneering book on the American realist painter George Bellows—Morgan had purchased the painting in 1952, a year after working briefly for the CIA in Greece. When Morgan traveled abroad, Frost borrowed the picture for his own Amherst house, and when Frost served as consultant in poetry at the Library of Congress, he asked to have the picture hung in his office. Already a passionate admirer of Wyeth, Frost approached the artist in 1953, without success, to collaborate on a new edition of his landmark book of poems North of Boston (1914):

You wouldn’t be illustrating it, but gracing it with something in a spirit I can’t help thinking kindred to mine. You and I have something in common that might almost make one wonder if we hadn’t influenced each other, been brought up in the same family, or been descended from the same original settlers.

As Frost’s eighty-fifth birthday approached in 1959—the same birthday at which Lionel Trilling famously described him as a “terrifying poet” rather than the homespun Yankee sage who “reassures us by his affirmation of old virtues, simplicities, pieties, and ways of feeling”—Morgan proposed that Wyeth paint the poet’s portrait. Wyeth, who disliked painting portraits (“Most of my portraits would have been better if I had removed the figures”), gently refused, claiming that, in pictures like Wind from the Sea and Christina’s World, he had “painted his portrait dozens of times.”

Nancy Anderson, drawing on an essay by Francine Weiss included in Rethinking Andrew Wyeth, discerns intriguing connections between Wind from the Sea and “Home Burial,” one of the narrative poems in North of Boston, in which a husband and wife respond differently to the loss of their first child. The wife can’t get over her grief and is appalled that her husband has apparently moved on. She stands at the top of the stairs looking out a window. He mounts the stairs to take a look for himself as she descends, threatening to leave the house as he drones insensitively on, touching inadvertently on the association of windows with graveyards that we see in Wind from the Sea, and their own blighted marriage:

I never noticed it from here before.

I must be wonted to it—that’s the reason.

The little graveyard where my people are!

So small the window frames the whole of it.

Not so much larger than a bedroom, is it?

Dismissing Frost’s bucolic imagery as of secondary importance, like his own supposedly “rustic scenes,” Wyeth praised instead the poet’s “strangely abstract meanings—he’s an amazing witch doctor, spidery, flashy, dark and light all at once.” Wyeth insisted, in his conversations with his biographer Richard Meryman, that he himself was an “abstractionist.” The two artists shared a sharp clarity of design, almost geometric in poems like “Home Burial,” with its frames and diagonals and abrupt changes of vantage point. Likewise, Wyeth achieved a geometric rigor that almost recalls Mondrian in pictures such as the grid-like, squares-within-squares Off at Sea (1972), a painting of a bench in a church vestry with windows looking out, in which a sitting boy has been painted over (though his shadowy form is now reemerging through the aging tempera like a revenant) and replaced by a single clothes hanger.

In the evocative Groundhog Day (1959; Philadelphia Museum of Art), Wyeth discarded the seated figure of Anna Kuerner from an early study and reduced the table setting to a single knife, a white plate, and a teacup and saucer. As in so many of Wyeth’s paintings, one feels that someone has died. Looking around at so many stark, color-starved, threadbare, wintry paintings, one has the impression that it’s always Groundhog Day in Wyeth’s world, with spring in doubt. And maybe one of the things that is dying in these pictures is the tradition of realist painting itself, at least of the kind that Wyeth felt he was painting.

When Hopper asked him to support a new magazine, Realism, launched in 1953 to counter the Whitney’s alleged neglect of realists, Wyeth demurred, calling abstract art “the toughest neighbor realism has had to put up with for years.” In one of his darker remarks about representational painting in a time of abstraction, he wrote, with rueful pride, “I’m going to put an end to this type of painting…. I’ve finished it off.”

4.

It’s possible to feel, when taking in this admirable show, that the National Gallery is trying to substitute a more palatable and “abstract” Wyeth, airbrushed of his Republican Party values (he painted both Eisenhower and Nixon) and his naive patriotism. Surely he was channeling Norman Rockwell when he painted, in 1950, Young America: a boy on a bike in cavalry attire trailing a foxtail in red, white, and blue, which Wyeth claimed represented “the vastness of America and American history,” including “the plains of the Little Bighorn and Custer and Daniel Boone and a lot of other things.” One tires of pictures that show off the weapons of a local farmer, including a disturbingly slapstick composition in which his sniper’s rifle points back at his gnome-like wife, who resembles Georges de La Tour’s fortune teller.

A more persuasive hint of menace lurks in the circling vultures in the marvelous Soaring (1950), which old N.C. told Wyeth wasn’t a picture at all before Lincoln Kirstein wisely encouraged him to finish it. Alexander Nemerov intriguingly suggests that Night Hauling (1944; Bowdoin College Museum of Art), ostensibly depicting a thief robbing a lobster pot amid liquid phosphorescence, derives some of its sheer oddness from its openness to another realm of contemporary imagery altogether, a pilot approaching a sleeping city at night. Looking at arresting pictures like these, one understands Mark Rothko’s observation that Wyeth’s paintings were “about the pursuit of strangeness.”

Strangeness pervades the final room of “Andrew Wyeth: Looking Out, Looking In,” in which paintings from the same year as Wind from the Sea, including the Whitney’s Spool Bed (1947), evoke the ghostly aura of an abandoned house in Maine with a damaged blue window shade. The pictures recall Robert Frost’s similarly strange “The Black Cottage,” in which a minister and one of his parishioners press their faces to the glass above the “weathered window-sill” of a house abandoned after the death of its owner. The house belonged to a woman who staunchly supported the North in the Civil War, and Jefferson’s “hard mystery” that “all men are created free and equal.” The minister imagines a desert island devoted to truths abandoned like the house itself, “truths we keep coming back and back to.”

The final lines of Frost’s poem are strangely consonant with the window-laden imagery and dreamlike, elegiac mood of some of Andrew Wyeth’s most entrancing work, art that, like Frost’s abandoned truths, we keep coming back to:

So desert it would have to be, so walled

By mountain ranges half in summer snow,

No one would covet it or think it worth

The pains of conquering to force change on.

Scattered oases where men dwelt, but mostly

Sand dunes held loosely in tamarisk

Blown over and over themselves in idleness.

Sand grains should sugar in the natal dew

The babe born to the desert, the sand storm

Retard mid-waste my cowering caravans—

“There are bees in this wall.” He struck the clapboards,

Fierce heads looked out; small bodies pivoted.

We rose to go. Sunset blazed on the windows.

-

1

Neil Harris, Capital Culture: J. Carter Brown, the National Gallery of Art, and the Reinvention of the Museum Experience (University of Chicago Press, 2013), pp. 438–442. ↩

-

2

See Robert Hughes, “The Rise of Andy Warhol,” The New York Review, February 18, 1982. ↩