I remember quite well the first time I saw the paintings of Sigmar Polke. It was in 1982, a time when a new generation of American artists, and a generation concerned with painting—which had not been the case with young artists for years—was coming to the fore. The few paintings by Polke on view at the Holly Solomon Gallery, then in SoHo, had a freakish power. Here was an only vaguely known, or for many of us a previously unheard of, German artist who, in works dating from 1972, had brought off with great confidence something similar to what one was seeing, and being excited by, in the new American paintings by, among others, Julian Schnabel, David Salle, Carroll Dunham, and Terry Winters.

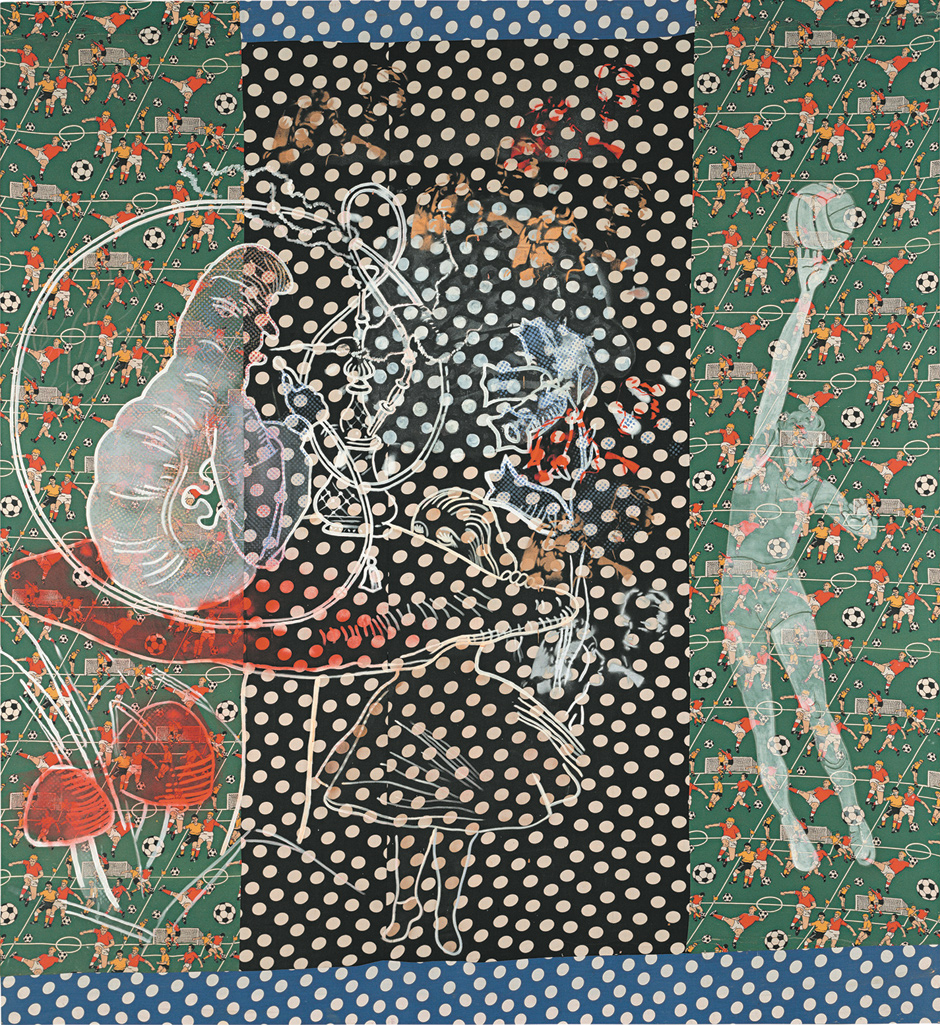

The Polkes were, in the simplest terms, crosses between tapestries and Cubist collages (and could be six feet or more on a side). Those initial works and others one eventually saw each presented a kind of floating world. It was a terrain where snippets of faces or figures taken from an ad, a cartoon, or a news photo, or that might be recognizable on their own—Alice, say, from Alice in Wonderland, or a figure from Goya, or Hopalong Cassidy—were magically interwoven with, or painted over, patches of fabric or abstract markings. There might also be splashy pours of paint, stenciled areas, or clusters of dots.

The paintings didn’t exactly have a larger literary or political story to tell. Yet Polke had a pleasingly uninsistent feeling for worn and lowly items—whether inexpensive, commercially printed fabrics or cheesy images from newspaper cartoons showing tubby office manager nobodies storming off in different directions—and this feeling for the everyday lent an unobtrusive human warmth to his work. He assembled his stenciled areas, quotes from ads, and stitched-in zones of fabric with seeming speed and a natural’s sense of how colors play off each other. His nonchalance was marvelous in itself.

In time, one learned that there was much more to Polke than what might be called those tapestry pictures. He began to exhibit in New York, and in 1991 a large retrospective, begun the previous year in San Francisco, came to the Brooklyn Museum. In 1999 the Museum of Modern Art mounted a significant exhibition of drawings done between 1963 and 1974. Noteworthy shows devoted to other aspects of his work were held in Dallas and Chicago (as well as throughout Europe, of course), and by the time he died, in 2010, at sixty-nine, it was clear that Polke was a phenomenon. His ever-changing body of work included a period in the 1960s when he was a kind of Pop artist and a period beginning in the 1980s when his pictures were abstract and, Merlin-like, his concern was the creation of new forms of paint.

He sometimes made these new paints with toxic and illegal substances—substances that would make the colors change depending on the light or room temperature, and that made the finished paintings, which might be in shades of purple or smoky yellow, seem “alive” in some way. Polke also made pictures with stained glass, and in works done on paper with photocopiers, or with glass lenses placed over images—the same process used for those postcards where Jesus might wink at you, depending on how you hold them—his goal seemed to be the capturing of instability in itself.

The Museum of Modern Art has now brought together, in one of the largest shows it has assembled, the most complete overview of Polke’s art that any museum has attempted. It is a remarkable and challenging event. Polke was funnier, brainier, and more ferocious in his need to experiment than, it can seem, many artists are. He was also a nonstop self-educator and a rarity among artists in that he could make his verbal wit an element in purely visual pieces. A delight in this vein is Goethe’s Works (1963), a small, maroon-colored horizontal painting with dark vertical spaces placed regularly, denoting, we realize, the separate volumes (there are five) in the master’s oeuvre. In 1969 the artist topped the joke with Polke’s Collected Works, a longer horizontal rectangle in the same color with more vertical spaces (seventeen volumes).

Most of all, though, Polke was a one-man think tank for new and invariably idiosyncratic ways to make paintings. Surely his coming of age in the 1960s—when, in art schools, it was held that painting as an art form was finished—contributed to the way we always seem to hear him say, as we stand before one new kind of picture after another, “You think painting is dead? Try this!” A picture by Polke thus exists as a unique and distinctly physical, hand-fashioned entity—and, at the same time, it has the weight of an idea, a suggestion, or a prototype for someone to pick up on. It is a recipe that can leave you charged up, especially if you feel you are on his wavelength; but at the next moment you can wonder if there is any ground beneath you.

Advertisement

The present show, organized by Kathy Halbreich, who began working with the artist on it in 2008 (and has contributed a probing and sensitive essay in the catalog), underscores the multifariousness of Polke’s art by presenting aspects of seemingly everything he did. Where previous exhibitions concentrated on his painting and drawing, the Modern has included as well generous numbers of Polke’s photographs (many doctored in rash, graffiti-like ways) and some of the notebooks he was always filling with sketches, Rorschach blots, and clippings from newspapers and magazines. There are banners and collages, and in movies that he apparently made in great number—they are projected here and there straight onto the gallery walls, as if they were another painting or drawing—we see the workings of an omnivorous eye, gobbling up everything in its path and apparently happy to include every blurry bit and double exposure picked up along the way.

Seeing so many disparate works may be disorienting even for viewers who think they know the artist. The situation may at first seem magnified by the museum’s decision to dispense with wall labels (the viewer consults instead a pamphlet). The show’s first, large room is in fact a trial in this regard, because it is a survey of Polke’s entire career. But after that, with a chronological layout and helpful, straightforward text panels appearing periodically, a viewer may find that not having labels turns out to be a relief.

What has been lost by the exhibition’s inclusiveness are more of the kinds of paintings I have referred to as tapestries—that is to say, pictures that date largely from the 1980s in which Polke the assured placer of forms, the sensuous colorist, the sometime quoter of this or that fragment from a newspaper or old book, and the manipulator of different kinds of paint surfaces can all be seen at once. I may speak from a conservative taste in wanting more of such works. Still, the show as constituted turns its back somewhat on the more sheerly pleasurable and beautiful aspects of Polke’s art. Yet the exhibition is invaluable in its own way. It makes us realize how much we have not known about this influential and elusive figure. It deepens our sense of Polke the person, which in turn enriches his art.

Born in eastern Germany, Polke escaped to the West with his parents in 1953, when he was twelve. Given his clear love of the many materials that can be made part of an artwork—and at the same time his offhand and impetuous, even roughhouse, way of handling them—it is perhaps significant that his father was, we learn, an architect. As a teenager, Sigmar was apprenticed to a stained-glass maker, and by his early twenties he was an art student in Düsseldorf (and eventually a friend of the painter Gerhard Richter, who had also come over from East Germany).

By the age of twenty-two, in 1963, Polke had made a little place for himself on the art map with pictures that show him working out his own versions of Pop art, the liveliest movement of the moment. Polke’s paintings of images (such as showgirls) from newspapers or magazines are quite different from the New York paintings of Mickey Mouse or Marilyn Monroe. The American Pop pictures have the size and force (and, in meaning, represent the flip side) of Abstract Expressionist canvases. Polke’s versions are, unexpectedly, intimate in spirit and sometimes almost luscious.

Whether done by Polke or Roy Lichtenstein, Pop pictures are in good measure about recreating images that have already been reproduced—usually offset printing, where the image is made up of countless dots—in some publication. When that news photo, say, is magnified, the individual dots, some densely packed, others more on their own, become visible (it is like zooming in on a colony of ants). Polke’s idea was to paint this terrain exactly as he saw it, including any imperfections in the original process (unlike Lichtenstein, who was deliberately uniform in his methods). Polke’s result is pictures—Girlfriends (1965–1966), for instance, where two movie stars face us in seduction mode—that seem to crawl and squirm and drip with life as we look at them.

Advertisement

It wasn’t just Pop art, though, that Polke was looking at with an irreverent or critical eye. His targets included the color abstractions of the time and the then-budding phases of Minimalism and conceptual art. An elegant white painting from 1967 titled Solutions, which is made up only of one line of addition after another (as in this plus that equals something), calls to mind Sol LeWitt and Carl Andre—who are skewered a bit as every line of addition comes out, wonderfully, wrong. Maybe even better is a predominantly white 1969 painting that has one corner precisely painted black. At the bottom it has the words, in German (which also form the work’s title), Higher Beings Commanded: Paint the Upper-Right Corner Black! (One suddenly sees Ellsworth Kelly going down the drain, and possibly taking Kazimir Malevich with him.)

But then in the 1970s, when Polke was in his thirties and was now a name in the German art world, he made a risky and dramatic overhaul of his work. He didn’t do this in a programmatic or consistent way, and it isn’t described as such in the Modern’s catalog. But we clearly see Polke, in his pictures, shelving the gnomic, questioning, and satirical tone he had maintained and, in effect, expanding his art. He started to become a painter who needs to use not just his wrist but the full sweep of his arm. He began making literally messy artworks.

He went to live in a commune, apparently with his wife and their two children—biographical details are scant in the Modern’s catalog, as they are in all the Polke catalogs I have seen—but much time was spent with a companion, and he and his wife were eventually divorced. He traveled continually, landing in places such as Afghanistan, Pakistan, Southeast Asia, Brazil, and western Australia. He went, too, to the not-so-placid New York City of the time, where he made a suite of almost bruised-looking photographs of life on the Bowery. Based on the movies and pictures he created in this era, he clearly thought of the period as one in which to stretch his wings sexually, and he makes explicit, in references in his art, that hallucinogenic drugs were a major part of the program.

It is this work of the 1970s, comprised mostly of photographs, movies, large drawings, and collages, that has been left out of most comprehensive Polke shows. Based on the examples at the Modern, one can see why. As works of art, many of the displays feel insubstantial. Many of the diary-like and overstuffed collages, and the black-and-white photos with color thrown on here and there, seem merely jazzed up. Yet Polke emerged from the decade truly transformed. In the early 1980s he began painting with a gusto and an ambitiousness he had not shown before. His paintings could now be enormous in size, and it was now that his studio became something resembling an alchemist’s lab. And in pictures from 1984 that present watchtowers (and in an impressive picture entitled Camp, which is not in the show), he took on—although he didn’t actually say this—his country’s racked modern history.

Most of the watchtower paintings present, from below, a lone, looming tower. It is a structure loaded with bitter connotations. Wood towers such as these, we read in the catalog, are used by hunters searching for game, and they were employed by the East German government as lookouts from which to shoot people trying to escape to the West. They instantly and mostly bring to mind, of course, the concentration camps.

By Polke’s standards, the pictures, which include unsubtle references to prison and security cards, are obvious. Yet the watchtower paintings—the Modern is showing six of the seven in the group—are undeniably gripping. Many in the vicinity of ten feet high, and each different from the others, they present wildly inventive mixtures of stenciled areas, a variety of particular paint substances, photography, and patterned fabrics—and their richness as objects wins us over.

It has been said that Polke was less involved in distinctly German themes than the other preeminent German painters of his generation, whether Richter, Anselm Kiefer, or Georg Baselitz. All of them, though, were born before or during the war years, which meant that their young lives were conditioned by the Nazi experience, the government’s collapse, the markedly difficult postwar decade, and, for Polke, Richter, and Baselitz, the tensions of having lived for different lengths of time in East Germany before getting to West Germany. And even if he had not done the watchtower pictures it is clear that Polke shares with these painters an instinct about art that might well be a response to their country’s past. It is a feeling for images that are somehow untrustworthy, damaged, or merely unstable.

For surely there is a connection between Polke’s quest to create paint substances where the colors will change depending on ambient conditions or over time—or his taste for pulling the rug out from known styles—and the way Baselitz as a younger man made paintings of images being torn in different directions, or the way Kiefer early on made shifting landscapes by layering straw over photographs, or the way Richter could make a viewer physically queasy when looking at his paintings of what appeared to be blurry black-and-white photographs. Get close to one of Richter’s recent, abstract works, which are comprised only of long, thin stripes of different colors, and you may be hit by the same slight seasickness.

Then again, Polke’s being a member of a very particular German generation ought not to be taken as the one true source of his art of instability. Certainly, his background as the son of a man Halbreich calls “a master craftsman,” combined with Polke’s temperamental impishness and a son’s natural desire to do things differently than his father did, might play a part in the way he continually joked with and undercut whatever is traditional and polished. By the same token, there is a third Polke, an artist who might be called a secular shaman and whose chief goal seemed to be the search for sheer transformative energies.

Much of Polke’s liveliest later work was about ways to capture movement. Seeing Rays, a painting from 2007 where we look at a scene that has a corrugated glass lens in front of it, is a prime example of this and one of the treats of the exhibition. Behind the woozy-making glass front of this black, white, and gray picture we see an image that Polke has taken from some source and possibly altered. It shows a number of fellows from an earlier century in states of wonder as they encounter lines of force descending from a dragon in the sky. As you walk back and forth before Seeing Rays, the image keeps changing, and you feel like one of the confused and elated watchers yourself.

Polke’s spirit as a person was seemingly so ironic, canny, and comic, and he could be so shrewd and witty in his recorded statements about his work, that thinking of him as someone who was to some degree receptive to “seeing rays,” or who “wanted to believe in the paranormal,” as we read in the Modern’s catalog—or who could look for answers from telepathic sessions, horoscopes, Geiger counters, or hashish—may always come as a surprise. But even in his early work, a viewer comes to realize, he was leaving hints. One of the odder and most memorable images in the exhibition, for example, is from a German TV show from 1969 where we see the young Polke as a kind of sleepwalker in different places and then, strikingly, creeping along beside the Berlin Wall, his ear to the structure. He is listening, but for what? Then, too, there were those “higher beings” who came to him that day and “commanded: paint the upper-right corner black!”