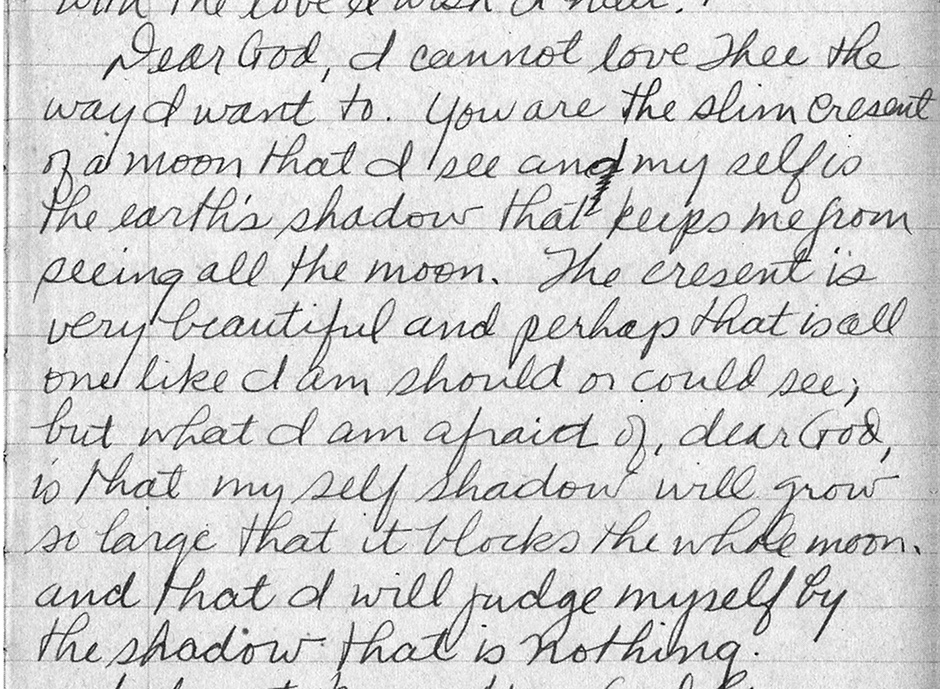

For some weeks before I read Flannery O’Connor’s posthumously published A Prayer Journal straight through, I read around it. The book’s length was not the problem. (At forty pages, not including a facsimile of O’Connor’s handwritten notes, this lovely volume rests in the hand like a collection of verse.) Nor was the ostensible subject matter—O’Connor’s Catholicism. Rather, what put me off were the dates she produced it. Written between 1946 and 1947 and more or less abandoned when the burgeoning author was twenty-two, this apprentice work emerged when O’Connor, a Georgia native, was not too long out of the South, and enrolled in the University of Iowa’s Writer’s Workshop. While I looked forward to her no doubt interesting views on belief, I didn’t want to stumble across those aspects of O’Connor’s past that were of her time and place, a segregated world where “nigger,” for example, was not a sliming slur, but an epithet.

She grew up in a world defined by segregation. Born to middle-class Irish-American Catholic parents in Savannah, Georgia, in 1925, O’Connor, an only child, was herself part of a minority. Along with blacks and lawyers, Savannah’s Catholic population was banned from the Georgia Trust of 1733; in 1916, the Convent Inspection Bill became law. “Under this weird legislation,” writes Brad Gooch in his biography of O’Connor, “grand juries were charged with inspecting Catholic convents, monasteries, and orphanages, to search for evidence of sexual immorality and to question all the ‘inmates,’ ensuring that they were not held involuntarily.”

In short, belonging was provisional, and society was fueled by exclusion and hatred. O’Connor’s brilliant mature work showed all that, and more: how divine intervention—the hand of God—looked on the map of a civil rights era world. No one was safe there, least of all those whites who tried to blindly uphold the old order with mean, red-faced grit.

But O’Connor’s themes and interests—redemption, mystery, transcendence, bigotry, all depicted in a hard, ecclesiastical light—had only the crudest relationship to the work she would produce in graduate school. When she arrived in Iowa City, escorted by her widowed mother and lugging a fifteen-pound muskrat coat to ward off the impending winter chill, she did not know what she wanted to say except that she needed to say it.

The tales O’Connor produced while at Iowa eventually made up her master’s thesis, called “The Geranium: A Collection of Short Stories,” which was completed in 1947, five years before she published Wise Blood, her first novel. By then the girl from Georgia had become an artist. Her master’s thesis, on the other hand, is a book by a student who had yet to find the courage or the intellectual means to leave her people. Indeed, many of the blacks in O’Connor’s first stories, for instance, are referred to as “niggers”—evil, shiftless, funky, and shut off from the narrow world of her white characters. In Iowa O’Connor was still writing from inside her whiteness, its presumed superiority, certainly according to the laws of her provisional tribe. Family always meant the world to her. (Her father died of lupus in 1941, the disease that would claim her life twenty-three years later.) And it’s family that she was able to criticize and feel tenderly toward, especially when it wasn’t necessarily traditional, like the grandfather and his boy in her unsurpassable 1954 tale “The Artificial Nigger.”

In a 1963 talk, O’Connor said that the southern writer was particularly fortunate because the region’s insularity and hostile attitude toward strangers made the ground fertile for fiction—the South had a rich, dense idiom to draw on. And what is family but a group that’s hostile or suspicious of strangers? (O’Connor’s aptly titled 1954 story “The Displaced Person” takes bigotry and paranoia in the South’s black and white families as its theme.) Despite the fact that O’Connor, the industrious Iowa graduate student, was reading about larger themes in Kafka and James and Proust for the first time, she had not yet, while writing the Geranium stories, left the Main Street in her mind. It would take her many years to face what all artists must: feeling “orphaned” by family, the better to describe it. O’Connor’s journal was a step in that direction; its loose format provided a degree of freedom that the writer did not allow herself in her carefully tended, academic tales.

A published journal usually gets to be that way because it’s considered as riveting to read as any fiction, but with the extra fillip that it’s real, and that the scenes and intimacies exposed will end in a satisfying this-is-how-I-did-it way. O’Connor’s fifth posthumous book doesn’t really offer any of that. No physical self-description crowding the pages. No details about her surroundings or classmates. No proms or dances or scenes of love. (Indeed, the book’s austere aura reminds one of the view that Elizabeth Hardwick and Elizabeth Bishop took in their joint essay about her: “Most of all she was like some quiet, puritanical convent girl from the harsh provinces of Canada.”) Instead, what O’Connor produced was a colloquy, a series of notes that are half psalm, half pensée—songs of inquiry that center, largely, on how best to serve Him in every aspect of her creative and noncreative life.

Advertisement

The mature O’Connor would have ridiculed the earnestness of some of these entries—“My dear God, how stupid we people are until You give us something. Even in praying it is You who have to pray in us”—and for the same reasons she mocked Simone Weil: all that grim self-seriousness. (In 1955 O’Connor wrote to a friend, expressing her desire to write a novel about a Weil-like figure: “What is more comic and terrible than the angular intellectual proud woman approaching God inch by inch with ground teeth?”) But there is a great deal one should take seriously while reading O’Connor’s journal, and that includes the writer’s unintentionally revealing view of herself, especially as a woman, and a thinker.

By now much has been made of the young intellectual women in O’Connor’s fiction, and how these generally unhappy, sometimes willfully unattractive agnostics reluctantly return home to the “Christ-haunted South,” sick with contempt for their small-town surroundings after a spell away, up north—that mecca of thinking and modern alienation. But what about the men these women are attracted to? Usually they have some specious connection to the church, or faith, that legitimizes them, socially at least, in the eyes of the elders.

They also have language. O’Connor’s outsider boys—an outsiderness the young women in her stories generally identify with—use their wild, stately, dramatic speech to describe what they see looking past all that anger and physical difference: a woman, first, and then a woman with needs. But in O’Connor’s world heterosexual love usually turns out to be a devastating rip-off. (In her 1955 short story “Good Country People,” a Bible salesman runs off with a Ph.D.’s false leg.) Despite brilliantly imagining these feelings, O’Connor didn’t act them out herself (or did, in her fiction); her sublimated sexuality heats up her talks with God much more directly.

In the journal O’Connor keeps trying to break free of her erotic desires as she tries to break through to God, the better for Him to see her, direct her—as any absent father should, certainly in the imagination. In entries no longer than a thousand words each, sometimes undated, O’Connor expresses desire in one or two ways. She wants to be a good artist, but an artist with the complicated task of making His word live in a changing world. To not achieve this would be to “feel my loneliness continually.” God came before carnal love, and work came before other people. Like any young artist—and some not so young—O’Connor criticizes, in the journal, a number of other writers, the better to see herself. One way to make a world is to exclude others from it.

She reads Proust with a certain amount of admiration but distaste, too: his depiction of sex and desire does not resonate with supernatural love, that which links one to the Divine. Instead, he depicts the perverse, which is “wrong.” (“Perversion is the end result of denying or revolting against supernatural love…. The Sex act is a religious act & when it occurs without God it is a mock act or at best an empty act.” One wonders what O’Connor would have made of gay marriage.)

It would be easy enough to dismiss O’Connor’s aversion to Proust’s view of love if one did not hear the putdown in it. Back then, certain aspects of difference were punishable by law. Gay men, for instance, were still being arrested because of their desire; black men were being lynched for imagined infractions against white women. O’Connor’s moral stance is often fascinating when it comes to ideas about fiction. And when she limits her moralizing to herself, and the split she feels between the “I” of authorship and her self-disgust when that “I” asserts itself the better to write the words we’re reading—“I do not know You God because I am in the way. Please help me push myself aside”—O’Connor writes like no one else.

Advertisement

It’s only when, in her youthful zeal, she starts to blanket the world with her religious rigor that the book falls off, and one is reminded of another moralizing journal keeper: André Gide, who, in books like Madeline (1954), wrestles with his queer desire by making Madeline, his wife, a kind of Virgin Mary—untouchable, a presence to be talked at, projected onto, the better to understand himself. Madeline was as real to Gide as O’Connor’s female body was to herself.

Did O’Connor think of her loneliness and her need as a perversion as well? She could not help but be aware of all that postwar coupling going on in Iowa during her stay, when so many of the male students were on the GI Bill, and starting families. In his introduction, O’Connor’s friend W.A. Sessions says:

The prayers in her journal naturally emerged out of the busy classrooms, libraries, and streets of Iowa City. Her dorm room, which opened onto the only bathroom on the floor, was far from private. In that awkward room the young writer began her journal as she sat at a desk with her pens, pencils, and typewriter beside her hot plate (all the refrigerated items stood outside the window).

Writers create all sorts of shrines to their art. And it’s worth noting that, when O’Connor moved back in with her mother more or less for good in 1951, she worked in a similarly circumscribed space as well. It was as if she needed the world to physically close in on her so her mind and thus imagination could expand. On May 30, 1946, after a particularly intense period of reading the French Catholic absolutist Léon Bloy, O’Connor wrote this note in her journal:

I am a mediocre of the spirit but there is hope. I am at least of the spirit and that means alive. What about these dead people I am living with? What about them? We who live will have to pay for their deaths. Being dead what can they do…. No one can do again what Christ did. These modern “Christ’s” pictured on war posters & in poems—“every man is Jesus; every woman Mary”…have made Bloy retch. The rest of us have lost our power to vomit.

That wasn’t entirely true. O’Connor’s gorgeous soul sickness—her various judgments and hurts and desire to know and love her ever-mysterious Lord in what appeared to be a God-forsaken world—became even more powerful and singular after she finished “The Geranium: A Collection of Short Stories,” left Iowa, fell in love with the poet Robert Lowell and, later, a Danish bookseller named Erik Langkjaer, and suffered the pain of corporeal rejection in both cases. It was in those years, though, that she began writing those remarkable and often remarkably funny tales that showed what people looked like as they marched along in their tennis shoes, retching unto death. It was in her novels, and in her stubborn, real, and true short stories like 1953’s “A Good Man Is Hard to Find,” that her power to vomit found the perfect characters for her to expel—southern men and women who had a beef with Jesus. (The Misfit in “A Good Man Is Hard to Find” takes it upon himself to kill the living dead because Jesus didn’t. “Jesus was the only One that ever raised the dead…and He shouldn’t have done it. He thrown everything off balance.”)

By marrying her constant, troubled, and loving relationship to God to writing—to metaphor—O’Connor made a world, one in which the Divine did not take a back seat to the junk she saw in all those small southern shop windows, the emotional crimes tenant farmers leveled against blacks and plantation owners and “trash,” ugly hats bobbling along on barely integrated, garishly lit city buses all lighting the way home. Toward the end of her life, O’Connor added a kind of addendum to her prayer journal when she said:

We have to have stories…. It takes a story to make a story…one in which everybody is able to recognize the hand of God and imagine its descent upon himself.