Andrew Rossi’s documentary Ivory Tower prods us to think about the crisis of higher education. But is there a crisis? Expensive gambles, unforeseen losses, and investments whose soundness has yet to be decided have raised the price of a college education so high that today on average it costs eleven times as much as it did in 1978. Underlying the anxiety about the worth of a college degree is a suspicion that old methods and the old knowledge will soon be eclipsed by technology.

Indeed, as the film accurately records, our education leaders seem to believe technology is a force that—independent of human intervention—will help or hurt the standing of universities in the next generation. Perhaps, they think, it will perform the work of natural selection by weeding out the ill-adapted species of teaching and learning. A potent fear is that all but a few colleges and universities will soon be driven out of business.

It used to be supposed that a degree from a respected state or private university brought with it a job after graduation, a job with enough earning power to start a life away from one’s parents. But parents now are paying more than ever for college; and the jobs are not reliably waiting at the other end. “Even with a master’s,” says an articulate young woman in the film, a graduate of Hunter College, “I couldn’t get a job cleaning toilets at a local hotel.” The colleges are blamed for the absence of jobs, though for reasons that are sometimes obscure. They teach too many things, it is said, or they impart knowledge that is insufficiently useful; they ask too much of students or they ask too little. Above all, they are not wired in to the parts of the economy in which desirable jobs are to be found.

A fair number of the current complaints derive from a fallacy about the proper character of a university education. Michael Oakeshott, who wrote with great acuteness about university study as a “pause” from utilitarian pursuits, described the fallacy in question as the reflection theory of learning. Broadly, this theory assumes that the content of college courses ought to reflect the composition and the attitudes of our society. Thus, to take an extreme case that no one has put into practice, since Catholics make up 25 percent of the population of the United States, a quarter of the curriculum ought to be dedicated to Catholic experiences and beliefs. The reflection theory has had a long history in America, and from causes that are not hard to discover. It carries an irresistible charm for people who want to see democracy extended to areas of life that lie far outside politics.

An explicitly left-wing version of the theory holds that a set portion of course work should be devoted to ethnic materials, reflecting the lives and the self-image of ethnic minorities. But there has always been a conservative version too. It says that a business civilization like ours should equip students with the skills necessary for success in business; and this demand is likely to receive an answering echo today from education technocrats. The hope is that by conveying the relevant new skills to young people, institutions of higher learning will cause the suitable jobs to materialize. The secretary of education, Arne Duncan, believes this, and accordingly has pressed for an alternative to college that will bring the US closer to the European pattern of “tracking” students into vocational training programs. Yet the difficulty of getting a decent job after college is probably the smaller of two distinct sources of anxiety. The other source is the present scale of student debt.

Unpaid debt from student loans today exceeds credit card debt. The national total is more than a trillion dollars. And unlike an underwater mortgage, where the owner’s immediate trouble ends with foreclosure, arrears from unpaid student loans follow the student ever after.

This situation came about as a remote consequence of a generous idea. The Higher Education Act of 1965 laid the groundwork for Pell Grants and other loan programs, but the following decades saw a weakening of the belief that the federal government should subsidize intellectual curiosity. Ronald Reagan, as governor of California, led the withdrawal of support by the states for higher education; and many other states gradually cut back the appropriations with which they once helped universities to function well. The difference was passed on to students in the form of rising tuition costs; and tuition had to be paid for by reliance on loans in ever-enlarging quantities. The federal government will make $184 billion in profits from student loan debt over the next decade.

Advertisement

The financial crush has come just when colleges are starting to think of Internet learning as a substitute for the classroom. And the coincidence has engendered a new variant of the reflection theory. We are living (the digital entrepreneurs and their handlers like to say) in a technological society, or a society in which new technology is rapidly altering people’s ways of thinking, believing, behaving, and learning. It follows that education itself ought to reflect the change. Mastery of computer technology is the major competence schools should be asked to impart. But what if you can get the skills more cheaply without the help of a school?

A troubled awareness of this possibility has prompted universities, in their brochures, bulletins, and advertisements, to heighten the one clear advantage that they maintain over the Internet. Universities are physical places; and physical existence is still felt to be preferable in some ways to virtual existence. Schools have been driven to present as assets, in a way they never did before, nonacademic programs and facilities that provide students with the “quality of life” that makes a college worth the outlay. Auburn University in Alabama recently spent $72 million on a Recreation and Wellness Center. Stanford built Escondido Village Highrise Apartments. Must a college that wants to compete now have a student union with a food court and plasma screens in every room?

The question comes up in Ivory Tower because these are the sorts of things college recruiters boast of when they talk to prospective students. The model seems to be the elite club—in this instance, a club whose leading function is to house in comfort thousands of young people while they complete some serious educational tasks and form connections that may help them in later life. Corporate decisions, in such an organization, naturally require an administrative balcony of corporate heft. There are college presidents who now command salaries well over a million dollars a year.

“What gets measured gets improved,” runs the motto of the nationwide body culture franchise LA Fitness. Obedient to the same assumption, the administrative bureaucracy of universities has grown at a rate that far outpaces the growth of faculties; and much of the expansion goes to build up a regimen of institutional self-monitoring and self-measurement. But is it true that what gets measured gets improved? An obvious protocol of measurement is the consumer satisfaction survey. In colleges and universities, these are known as student evaluations. Much interested energy has been expended on the design and revision of these forms. And yet good and bad teachers were spotted easily enough in the days before evaluations. A hidden danger both of intramural systems and of public forums like “Rate My Professors” is that they discourage eccentricity. Samuel Johnson defined a classic of literature as a work that has pleased many and pleased long. Evaluations may foster courses that please many and please fast.

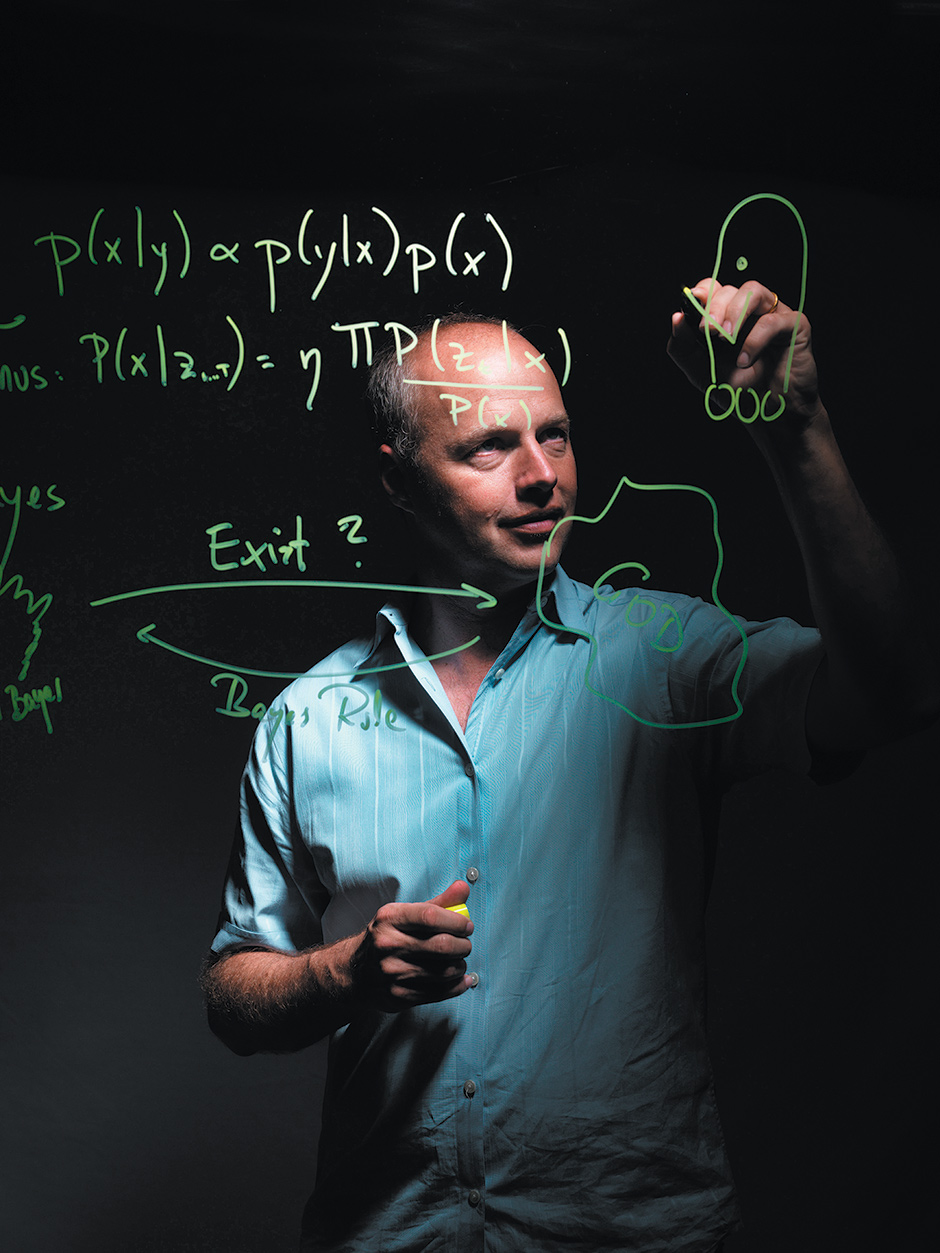

At the utopian edge of the technocratic faith, a rising digital remedy for higher education goes by the acronym MOOCs (massive open online courses). The MOOC movement is represented in Ivory Tower by the Silicon Valley outfit Udacity. “Does it really make sense,” asks a Udacity adept, “to have five hundred professors in five hundred different universities each teach students in a similar way?” What you really want, he thinks, is the academic equivalent of a “rock star” to project knowledge onto the screens and into the brains of students without the impediment of fellow students or a teacher’s intrusive presence in the room. “Maybe,” he adds, “that rock star could do a little bit better job” than the nameless small-time academics whose fame and luster the video lecturer will rightly displace.

That the academic star will do a better job of teaching than the local pedagogue who exactly resembles 499 others of his kind—this, in itself, is an interesting assumption at Udacity and a revealing one. Why suppose that five hundred teachers of, say, the English novel from Defoe to Joyce will all tend to teach the materials in the same way, while the MOOC lecturer will stand out because he teaches the most advanced version of the same way? Here, as in other aspects of the movement, under all the talk of variety there lurks a passion for uniformity.

One of the rock stars, the Udacity CEO Sebastian Thrun, becomes in Ivory Tower the subject of a separate character study. “There’s a red pill and a blue pill,” says Thrun (a theorist of artificial intelligence) to explain the new path he has chosen, “and you can take the blue pill and go back to your classroom and lecture your twenty students. But I have taken the red pill.” The sci-fi rap is just a way of saying he quit his job at Stanford to teach for Udacity. “For me,” says Thrun, “this is an interactive medium that exposes the student—just very much like in a video game.”

Advertisement

How much do we want teaching and learning to resemble a video game? But at this point, the appeal to amusement value shifts to an earnest profession of democratic concern. “We take the focus away from the professor,” says Thrun, “and put the focus back on the student.” Pause there for a moment. The AI innovator was asked to record his lectures because he is a star. At the same time, by rendering less glamorous types redundant in thousands of classrooms, Udacity says it will “put the focus back on the student.” How does that work exactly? In what educational state of nature was the “focus” on the student before the teacher came and took it away? And now that Udacity has put the focus back—as if the very presence of the teacher was an aberration which the MOOC format has corrected—will the company at last render even the star redundant?

A MOOC lecturer may interact with a small cross-section of students, but in the nature of the artifice, where class enrollments may soar upward of 100,000, this will never be more than a specimen group. A conventional delivery system for “the personal touch” in the MOOC format is the so-called “flipped classroom.” Here a teaching assistant circulates in a roomful of students who have watched the assigned video, and helps them to sort out questions about details. The assistant—as Ivory Tower suggests with a single understated caption—will often turn out to be somebody who was once a professor but whom economies facilitated by MOOCs have demoted to the status of section leader. At the heart of the

MOOC model is the idea that education is a mediated but unsocial activity. This is as strange as the idea—shared by ecstatic communities of faith—that the discovery of truth is a social but unmediated activity.

Still, however fanciful the conceit may be, the MOOC movement has a clear economic motive. Many universities today want to cut back drastically on the payment of classroom teachers. It is important therefore to convince us that teachers have never been the focus of real learning.

As things worked out in Silicon Valley, reality checked the dreams of Udacity. In 2013, the company was awarded a trial of its offerings in a contract with San Jose State University; and in July of that year, scores were posted for its spring term entry-level courses. The pass rate in elementary statistics was 50.5 percent; in college algebra, 25.4 percent; in entry-level math, 23.8 percent. Teachers have been fired en masse for results like these by administrators or politicians who would not sit for an explanation.

A less pretentious alternative to university teaching and learning is suggested by Peter Thiel, the cofounder of PayPal, who is described in Ivory Tower as a leader of the “UnCollege movement.” Thiel awards scholarships to persons of college age to support their self-education out of school. Some live, for that purpose, in the communal quarters of Education Hackerhouse in Silicon Valley. Thiel and his followers break down higher education into three goods that students are hoping to come into possession of: first, knowledge; second, a network of peers; and third, a credential. His approach, he thinks, may free them to work up the knowledge they need from the possibilities thrown open by digital technology. Along the way, living arrangements like the Hackerhouse offer a usable network of fellow students. As for the credential, it will come from whatever chance they make for themselves by following this elective path.

Thiel is wrong to suppose that all knowledge worth having can be quantified, that the main social good of four years of college has always been supposed to come from networking, and that intellectual authority is reducible to a credential. But the students on Thiel Fellowships who are interviewed in Ivory Tower seem alert and mentally alive. In a curious way, they show more spontaneity and more pleasure, and seem far less relentlessly organized, than many students now attending the better colleges and universities. Is it the absence of hand-holding—the sense that they are on their own—that has given them something of the freedom of college forty or fifty years ago?

Ivory Tower manages to encompass, though in foreshortened segments, a wide sample of the varieties of higher education as it is now experienced. We are shown the attractions that draw out-of-state consumers to risk the hazard and pay the price of a “party school” famous for pleasures as much as credentials. There are also dramatic moments of the sixty-five-day student occupation of the president’s office at Cooper Union, in a protest against the new requirement of tuition at a historically tuition-free institution. And we are shown the first day of the school year at Harvard, where CS50 (Introduction to Computer Science) has become the most popular course and its office hours draw hundreds seeking tutoring in two long lanes of tables.

The most instructive parts of the film are the segments on Deep Springs College in California and Spelman College in Georgia. The footage dealing with Spelman, a school for African-American women, illustrates the paradoxical fact that diversity of mind and intellectual self-confidence may flourish most where students from similar backgrounds, or sharing similar aims, live together and encourage each other. Deep Springs makes the point in a vastly different setting. The school offers the first two years of college to a small group of men—it is in the process of becoming coeducational—and its students undertake (as one of them describes it) “a two-year commitment to, in effect, drop out of the world.”

The pillars of education at Deep Springs are self-governance, academics, and physical labor. The students number scarcely more than the scholar-hackers on Thiel Fellowships—a total of twenty-six—but they are responsible for all the duties of ranching and farming, along with helping to set the curriculum and keep their quarters, on the campus in a California desert valley near the Nevada border. Two minutes of a Deep Springs seminar on citizen and state in the philosophy of Hegel give a more vivid impression of what college education can be than all the comments by college administrators in the rest of Ivory Tower.

Andrew Delbanco, a professor of humanities at Columbia University and author of College: What It Was, Is, and Should Be (2012), is the steady voice behind the film, a sort of chaperone or cicerone for the nonacademic viewer, and his explanations go far to organize the miscellaneous richness of the subject matter. We see Delbanco walking to his office and working at his desk, and hear him reflect on the crisis; and on the whole, a better and more reasonable voice could not be asked for. He wants much of the life of liberal education as he has known it to continue, and he detects the dangers in several of the up-to-date nostrums. Teaching at a university, he says, involves a commitment to the preservation of “cultural memory”; it is therefore in some sense “an effort to cheat death.”

Probably it is. But so are many other things in life: having children, founding a company or a charity, tending one’s garden. There is a pressure and a demand for human continuity beyond the dreams of standardized tests, cost-benefit readouts, and human resources questionnaires. “How shall a generation know its story/If it will know no other?” Edgar Bowers said it like that in his wonderful poem “For Louis Pasteur,” and the question may serve as a reminder of an elusive value that Ivory Tower conveys through other words and images. Universities exist not to answer the question but to register and reiterate its force.