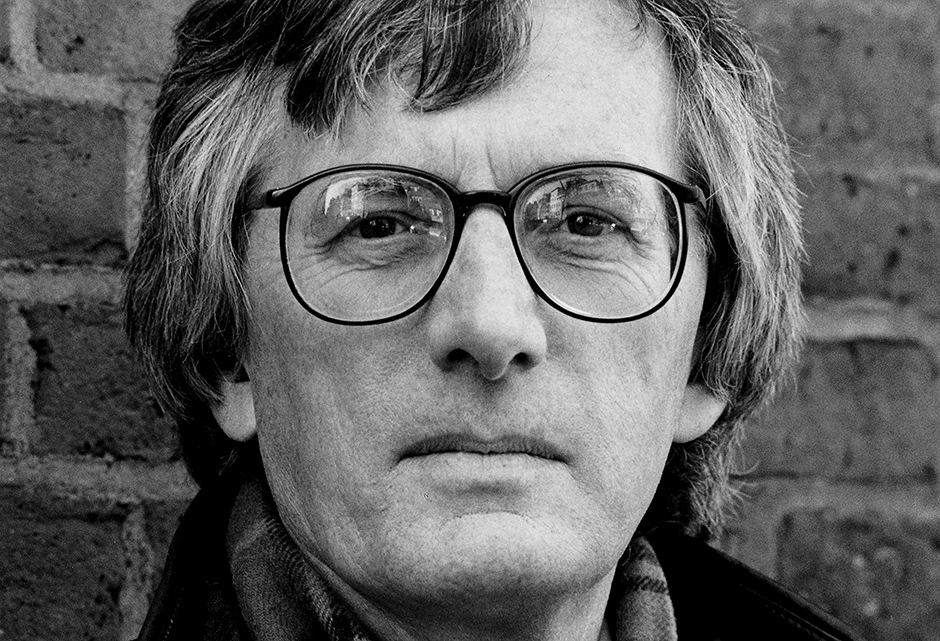

If you want to sample the work of Charles Wright, the nation’s new poet laureate, the best place to start may be Bye-and-Bye: Selected Late Poems, a collection whose marvels culminate in selections from Wright’s fine book Sestets (2009). Wright is sometimes thought of as a writer of wisdom literature, a backyard philosopher potting around in a material world he suspects might not even exist. If for their own sakes you are drawn to questions of “belief,” “materialism,” “the ineffable,” and so on, Wright’s “ascetic discipline” might be an “instruction” (I am sampling phrases from the blurbs on the back of this book). But I regard Wright’s focus on these questions to be, in fact, a fixation on them, an essential oddity of temperament that is more interesting, at least to me, than its symptoms. Temperament is Wright’s great, open variable: he is always solving for it by fixing the other terms. His poetry is therefore attuned not merely to its fluctuations in the moment, but to its own long arc, the history of its ups and downs.

Wright’s body of work conducts a longitudinal study of the moods as they shift and change in time. And yet, to carry out such a project obligates a poet to passivity, to routine, even to monotony, obligations that Wright, though resigned to them, sometimes seems to resent. Often his tenacious mellowness seems to fray. When it does, we hear the half-comic, half-rhapsodic tone of Wright’s poetry at its finest:

If I were a T’ang poet, someone

would bid farewell

At this point, or pluck a lute

string,

or knock

on a hermit’s door.

I’m not, and there’s no one here.

The iconostasis of evergreens

across the two creeks

Stands dark, unkissed and

ungazed upon.

Tonight, it’s true, the River of

Heaven will cast its net of

strung stars,

But that’s just the usual stuff.

As I say, there’s

no one here.

In fact, there’s almost never

another soul around.

There are no secret lives up here,

it turns

out, everything goes

Its own way, its only way,

Out in the open, unexamined,

unput upon.

The great blue heron unfolds like

a pterodactyl

Over the upper pond,

two robins

roust a magpie,

Snipe snipe, the swallows wheel,

and nobody gives a damn.

The orneriness we feel when we behold the grandeur of nature stems from our comparative inability, or so it seems to us, to do anything so beautiful as fly, blossom, or roust. What does Wright have to match the heron’s flight, the stand of evergreens? When compared to these spectacles, language, even the language of poetry, seems the least natural thing on earth. As the various registers (here lyrical, as in “net of strung stars,” there religious, as in “iconostasis”) jostle for predominance in these lines, Wright’s impatience builds: with “nobody gives a damn,” it bubbles over.

Since you cannot control for the moods without stabilizing the outside factors, Wright often finds himself sitting through nature’s reruns, his comic-bleak commitment (or resignation) to old news yielding its predictable harvest:

I sit where I always sit,

northwest window

on Basin Creek,

A homestead cabin from 1912,

Pine table knocked together some

30 years ago,

Indian saddle blanket, Peruvian

bedspread

And Mykonos woven rug

nailed

up on the log walls.

Whose childhood is this in little

rectangles over the chair?

Two kids with a stringer of sunfish,

Two kids in their bathing suits,

the short

shadows of evergreens?

Under the meadow’s summer

coat, forgotten bones have

turned black.

O, not again, goes the sour song

of the just resurrected.

Wright’s own “sour song”—his ironized commitment to repeating himself, to sitting where he always sits—reminds me a little of James Schuyler, another great transcriber of the uneventful, another poet who is “religious” insofar as he cannot ignore the fact that his attentiveness resembles prayer, and another student of the moods. Both could be confused for lovers of the ordinary per se, and both are overprized for their scenery, the birds and flowers against whose peacefulness our emotional ups and downs seem all the more inconvenient. The purpose of their sort of poem, which mimics vigils and devotional movements in an explicitly secular context, which logs hours and hours describing commonplace phenomena, is to isolate the unique time signature of interior life, revving and slowing all day, never at rest, as it plays out against the world’s enviably regular measures.

Bye-and-Bye is an utterly characteristic title for a volume of Wright’s late poems, which are usually reiterative (saying “bye” and then, after an interval, saying it again), warily redemptive even while being grimly fatalistic (it is death, of course, that will be arriving “by and by”), and, everywhere, self-mockingly self-elegizing, as though all his poems had to say, over and over, was “bye.” A whole category of groaners and bad puns (“spring buzz-cut on the privet hedge”) suggests the transfiguring power of the imagination while acknowledging its depleted morale. Wright has been saying “bye” for a long time: his late poems are solemn in their substance but comic in their basic predicament, that of the elegist who cried wolf. In the late poems, many of them nocturnes, the shadows of things rapidly overcome the things themselves; soon night will take over and the visible world (long Wright’s bread and butter) will “[ease] into earshot”:

Advertisement

No ledge in early December

either, and no ice,

La Niña unhosing the heat pump

up from

the Gulf,

Orange Crush sunset over the

Blue Ridge,

No shadow from anything as

evening gathers its objects

And eases into earshot.

Under the influx the outtake,

Leon Battista

Alberti says,

Some lights are from stars, some

from the sun

And moon, and other lights are

from fires.

The light from the stars makes the

shadow equal to the body.

Light from fire makes it greater,

there, under the tongue, there, under the utterance.

Nobody reads “Orange Crush sunset” and applauds its aptness, or quotes the phrase “unhosing the heat pump” when it becomes unseasonably mild. This is a special kind of slackened description that tells us a lot about the person doing the describing, a person who has himself formulated countless earlier descriptions of sunsets and heat waves, and who (as his almost reflexive acknowledgment of past masters, here the Italian architect and art theorist Alberti, suggests) sees his phrases as coming at the frayed end of a very long line of earlier formulations. The absurdity of trying to come up with fresh language every time the sun sets or the weather changes: one way to represent this problem is to eschew masterly phrasing entirely, and, finding language that feels decidedly minor, to shrug in the direction of description.

The attitude of cognitive readiness and the ambition to name fugitive phenomena in the nick of time no longer obtain for the poet in a world that seems rote and predictable. This leaves a huge surplus of mind left over for memory, which comes to seem more eventful than the events unfolding behind the gauzy scrim of the present. Here are Wright’s “College Days”:

All I remember is four years of

Pabst Blue Ribbon beer,

A novel or two, and the myth of

Dylan Thomas—

American lay by, the academic

chapel and parking lot.

O yes, and my laundry number, 597.

What does it say about me that

what I recall best

Is a laundry number—

that only

reality endures?

Wright cannot bear it that reality is weighted in favor of minutiae and data (laundry numbers, Pabst Blue Ribbon) and so his own remembered past will often yield to the storied past of philosophers, sages, poets, and artists, whose meditative company transports him far from “the merely personal” world of laundry and beer, “the names of things, past places.”

Wright’s poems display the raggedness of modeled attention, rather than the polish of “works of art.” But attention has the irritating tendency, when represented, to harden into forms; this is one of Wright’s primary themes: not a theme merely, but a practical problem. Every time a word replaces a perception, it narrows the dynamic range of the mind; every time a sequence of words, a poem, a book of poems, is finished, it leaves the flow of sentience from which it was plucked. Attention is radically temporal; in comparison with it, poetry, though a temporal art, feels very static, almost like a painting. These paradoxes are repeated over and over in Wright, in new forms and manifestations, because they are inescapable—they greet him every time he uncaps his pen:

For over 30 years I’ve looked at

this meadow and mountain

landscape

Till it’s become iconic and small

And sits, like a medieval traveler’s

triptych,

radiant in its

disregard.

Only a writer whose goal is the presentation of unstoppered awareness would regard as hard and “triptych”-like poetry so fluid, so limpid, so musical. Wright has made a potentially pat and overfamiliar metaphysics, one that downgrades the tangible particulars of “reality” in favor of the spirit’s hunches and hints, into something really thrilling: the practical aesthetic problem of how such a metaphysics might be represented in language.

Wright’s Sestets, sampled generously here, is his strongest in years. (It was followed by another excellent collection, Caribou, in 2014.) He was once, in his youth, a poet of aphoristic conciseness. He dilated his style to allow more experience in, but he has always seemed to speed past his luscious descriptions in order to get to the point. Sestets is all point: the aperture has narrowed again. These six-line poems read like the conclusive “sestets” of sonnets whose phantom octaves (along with the hypotheses they would have embodied), since we can so easily imagine them, simply go without saying. They are poems about the end, in tones as final and unblinking as can be imagined. Here is the first of two successive October poems:

Advertisement

Tenth month of the year.

Fallen leaves

taste bitter. And grass.

Everything that we’ve known, and

come to count on,

has fled the

world.

Their bones crack in the west

wind.

Where are the deeds we’re taught

to cling to?

How I regret having missed them,

and their

mirrored pieces of heaven.

Like egrets, they rise in the clear

sky,

their shadows

like distance on the firred hills.

These poems declare their bleakness as a precondition, yet they do their best to chafe against the self-impositions—that six-line limit, a blanched vocabulary—that embody it. Wright’s prosody, learned from Pound, allows him to “step” his lines vertically, making the poems seem much draftier—and longer—than their form permits. Here is the second October poem:

No wind-sighs. And rain-splatter

heaves up over the mountains,

and dies out.

October humidity.

Like a heart-red tower light,

now bright, now not so bright.

Autumn night at the end of the

world.

In its innermost corridors,

all damp and all

light are gone, and love, too.

Amber does not remember the

pine.

In Wright’s more luxuriant middle style, grim sentiment checked the language’s innate succulence. But here the language is reduced to a skeletal grimness (though Wright’s dark side will still allow him to title a poem, for example, “Hasta La Vista Buckaroo”), and the resulting poetry comes as close to epitaph-writing, for better and worse, as anything an American poet has written in a long time.

This book tracks an extraordinary consciousness through its emotional weather over the last twenty years, and yet it gives little evidence of having existed in the world we read about in the newspapers and in novels or see on television and in films. A mental model that rules those worlds out is obviously incomplete; but those worlds (Wright’s poems make us see this) are themselves catastrophically incomplete if they leave out the world’s “dark grace” and the struggle, as Wright has put it, simply “to record it.” This “recording” requires nearly daily attentiveness to the world: miss one day and the entire time-lapse sequence is ruined.

For this reason, Wright has always been a poet to counterpoint his fluid sense of thinking and feeling with the incursion of calendar time. As in Thoreau’s journals, these dates provide testimony to the marvels of the future: you can look in Thoreau’s autumn journal for the year 1860 to see about when to expect the maples to start turning in October (or you can if, like me, you live in Thoreau’s neck of the woods; if not, you will have the different sort of pleasure of imagining maples, one that I am denied). And yet, as Bill McKibben’s recent piece on climate change and Thoreau’s journals suggests, those marvels have been diminished.* The extraordinary continuity of Wright’s work, year to year, decade to decade, implies the future. We will need to consult him in the years ahead, as we do now with Thoreau, to figure out how to live in that future.

-

*

“What Would Thoreau Do?” The New York Review, June 19, 2014. ↩