Frederick Brown, the accomplished biographer of Zola, Flaubert, and Cocteau, has given us a kind of collective intellectual biography of France from the outbreak of World War I to the calamitous defeat of 1940. Despite the loss of so many talented young men in World War I, France seethed with intellectual energy in those years. Brown has singled out for particular attention Maurice Barrès, Charles Maurras, Léon Daudet, André Breton, Louis Aragon, and Pierre Drieu La Rochelle. Lesser lights also get their moment: wartime spy chasers, competing devotees of Joan of Arc on both right and left, admirers of Stalin and Hitler, crooks and gutter journalists. Many of them shared doubts about the Enlightenment’s faith in reason, canonical in the French Third Republic. They were attracted in varying degrees to the irrational, the spontaneous, the organic, or the subconscious. Brown deftly and economically analyzes the characters and opinions of many notable writers in this vein. He succeeds as usual in joining accurate scholarship to elegant and often pithy style.

The novelist, essayist, and later nationalist politician Maurice Barrès (1862–1923) towered over the early years of this period, and he receives an appropriate share of Brown’s attention. Barrès’s eloquence and passion in such works as his trilogy of novels Le Culte du Moi (Cult of the Self), published between 1888 and 1891, established so powerful a sway over young people at the turn of the century that he was called “the prince of youth.” In describing the emotional life and changing perceptions of a young man, Philippe, Barrès showed them how to liberate themselves from stultifying convention by asserting the primacy of individual selfhood.

His concern with individual energy soon turned toward national energy, and to anxiety about its perceived decline. He highlighted this problem in a three-volume “novel of national energy” (Le Roman de l’énergie nationale) whose best-known volume, Les Déracinés (The Uprooted), published in 1897, concerns a group of young men who are detached from their local culture by the abstract and universalist values of their schoolteachers. Torn from their moral moorings, they go up to Paris (following Julien Sorel, Lucien de Rubempré, and so many others) and fall into crime. Barrès found the answer in a cult of the soil and the dead of France (“la terre et les morts”). He supported the army and the church during the tumultuous (and unfounded) prosecution of the Jewish Captain Alfred Dreyfus for espionage (1894–1906).

Some of Barrès’s most exalted prose evinced a mystical attachment to certain historic sites along the German frontier. Another enthusiasm was French rural churches abandoned after the separation of church and state in 1905. Capable of stepping outside France, he wrote with admiration about Italy—he was close to d’Annunzio—and about Arab culture. During World War I he applauded the soldiers so ardently, long after the bloodletting had begun to arouse doubts, that the pacifist Romain Rolland called him “the nightingale of the carnage.”

But despite Barrès’s turn to nationalism and anti-Semitism, many of his early readers never quite got over their youthful infatuation with him. The young Léon Blum was not the only intellectual on the left who never gave up on Barrès, and tried to turn him away from the anti-Dreyfusard camp. The teacher and critic Jean Guéhenno, another ardent defender of Enlightenment values, wrote in his diary on January 27, 1942, “I always return to Barrès, ‘my old enemy,’ with the same pleasure.” Barrès’s capacity to join glorious prose with meretricious ideas recalls the Wagner he so admired. We can be grateful to Frederick Brown for ably presenting all sides of Barrès, surely the most influential French writer without a Pléiade edition of his works.

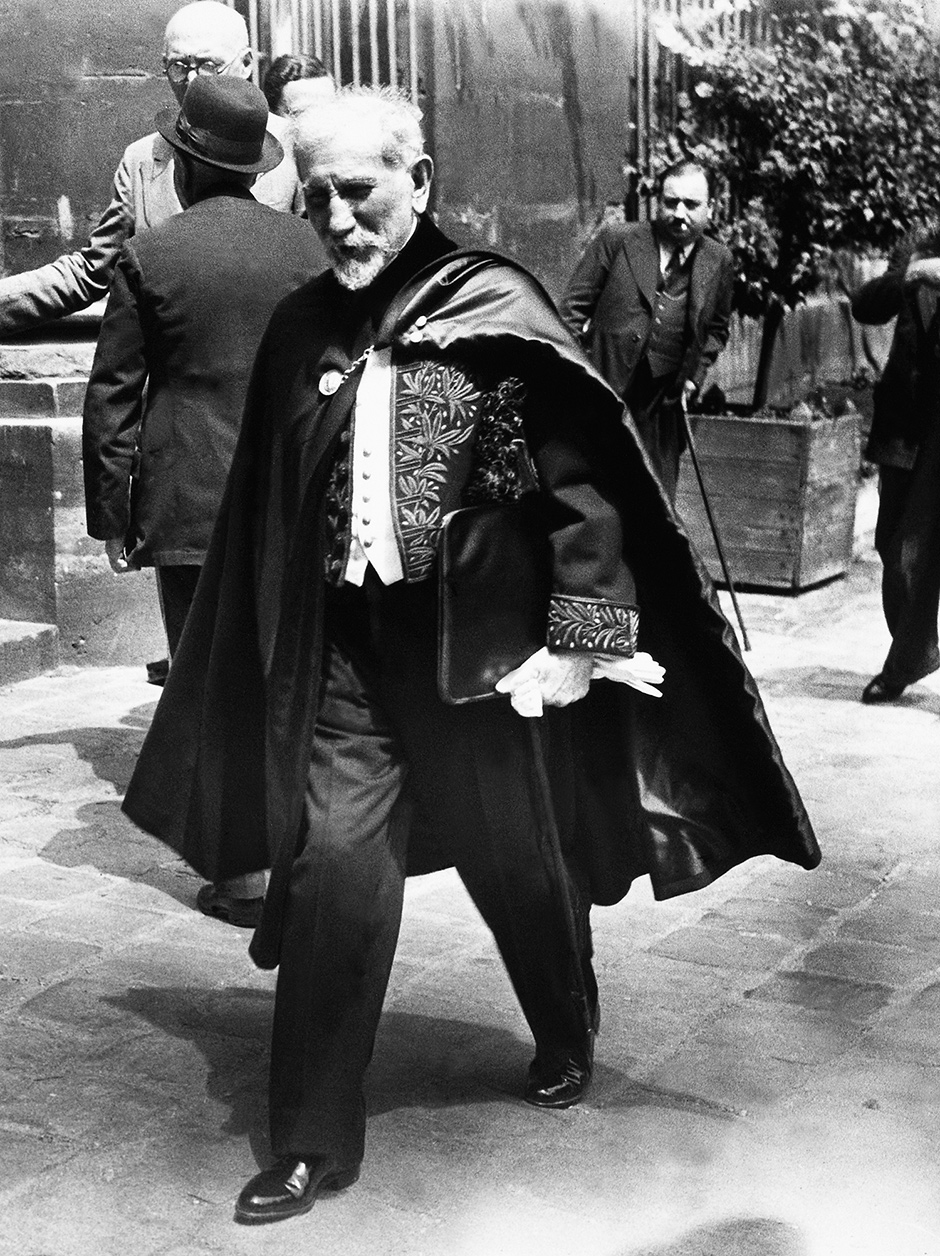

After Barrès’s death and pharaonic state funeral in 1923, Charles Maurras and his brawling lieutenant Léon Daudet remained to carry forward the anti-Dreyfusard cause: unqualified commitment to authority and virulent rejection of the French parliamentary republic. Maurras and Daudet were more narrowly partisan and more violently combative than Barrès had been (Barrès moderated his anti-Semitism when he learned of the record in combat of French Jewish soldiers and officers). Brown depicts Maurras’s notorious rigidity as the product of personal struggles with twin crises: he became deaf during his adolescence (which excluded him from the university) and he lost his religious faith. His Action française movement defended the restoration of the monarchy and church power for reasons of social order rather than faith. It attacked—sometimes bloodily—its enemies the métèques (a word Maurras coined to denigrate those he believed responsible for French decline: Jews, Protestants, foreigners, and Freemasons). Action française remained influential within the French social and military elite even after both the pretender to the French throne and the Vatican had disavowed it because of Maurras’s personal agnosticism.

Advertisement

The great innovation of Maurras’s Action française was to carry its doctrines into the street. Its bodyguard of young men, the Camelots du Roi (newsboys of the king), ostensibly hawking the movement’s newspaper, mounted public demonstrations and infested the university, where they beat up left-leaning professors. Partisans of the other side mobilized in their turn. Right-wing action squads now adopted the colored shirts first used by the left. The war had multiplied resentments ready to be fanned into action. The streets of interwar Paris were often filled with angry marchers.

Another postwar novelty was the discovery of the unconscious. Those who had seen firsthand the brutal effects of combat—André Breton and Louis Aragon both treated shell-shocked soldiers as medical orderlies—understood the power of the irrational. For them, reason and language were mere surface phenomena compared to a person’s deepest impulses and urges. Worse, reason and language were the agents of authority. To liberate the true inner self, they experimented with “automatic writing.” Brown has a field day with the way Dada and Surrealism mocked Barrésian heroics. But in 1927, the Surrealists began an improbable fling with the Communist Party, “seeking their salvation in Marxism-Leninism rather than in the id.” Breton soon broke with the Communists, while Aragon stayed with the Party through the worst of the Stalinist period.

In the Depression years of the 1930s, many other French intellectuals turned, like the Surrealists, from the private to the political. Brown’s principal figure here is the novelist and essayist Pierre Drieu La Rochelle. Drieu was tormented by doubts about himself as well as about France. His search for remedies to personal self-doubt took him through several marriages (one to a Jew- ish woman despite his anti-Semitism) and compulsive unfulfilling affairs. His search for remedies to French national decline took him past Surrealism and Marxism to fascism, which he finally decided offered the best recipe for restoring French virility and energy. Drieu’s suicide in 1945 signified a dead end that was both personal and public.

Although Brown presents a brilliant group portrait of significant intellectual and cultural leaders between 1914 and 1940, the portrait lacks a frame. Left to themselves, unwary readers are likely to adopt the one conveniently offered by a widespread popular prejudice: that a decadent France was doomed to defeat in 1940. Gratifyingly Brown never suggests such a teleology, though by making Marshal Pétain the subject of the last chapter he might seem to imply it. This view has become such second nature in the English-speaking world that it is likely to be imposed on Brown’s book by default.

There is no necessary link, however, between the interwar embrace of unreason and the French defeat of 1940. Had not Germans embraced unreason even more fully in the same years? Barrès is more readily linked to that ardent gambler Charles de Gaulle (a lifelong admirer of the author of Le Culte du Moi and Le Roman de l’énergie nationale) than to that risk-averse calculator Philippe Pétain. Indeed the best current scholarship about the fall of France in May–June 1940 rejects the familiar explanations of treason, defeatism, and disarmament within the Third Republic (the Vichy government’s self-justifying explanation, which has proved astonishingly durable).

The French high command had enough troops and materiel in most categories (including the best tank of the campaign), but it put them in the wrong places and used them counterproductively. The hastily improvised German attack through the Ardennes hills that today looks like an easy, decisive victory was in fact so risky that the German General Staff watching from Berlin had moments of panic.1 We can no longer legitimately frame the interwar period as a one-way street to the inexorable defeat of a degenerate people. And as for the Vichy regime that accepted German occupation, it was set up by a bureaucratic, military, and technological elite while many French devotees of “unreason” could be found either sniping from the sidelines in Paris, on Nazi stipends, or gambling rashly on Resistance and writing for underground publications.

There are other, more telling ways to frame the interwar years in France. Three weighty circumstances created challenges with which the French social and political system dealt ineffectively. First came the social and economic distortions produced by the world’s most destructive war up to that time. Then in 1929 the world fell into the Great Depression. The economic crisis had not ended when Hitler began to take his revenge for 1918. This time of fearsome stresses and feckless responses cost France its status as a Great Power. In the downward spiral many French people looked frantically for something better than the Third Republic and its official rationalism. It may legitimately be asked whether matters that properly concern a skilled biographer, such as Maurras’s notorious mental rigidity, offer the best clues to understanding such an era.

Advertisement

While every nation that took part in World War I had suffered, France had endured much of the fighting on its own soil and its 1,400,000 dead had the heaviest impact of any major belligerent because the French birth rate had been so low. Casualty rates were unevenly distributed, junior officers and peasant soldiers having been hit the hardest (many skilled workers were deferred to work in munitions plants). Inflation set off by wartime spending launched some fortunes while impoverishing many middle-class households. Wartime propaganda had exacerbated nationalism while refining the techniques of manipulating public opinion.

The second challenge—the Depression—arrived later in France than elsewhere. But it lasted far longer, in large measure because successive French governments persisted in deflationary austerity—cutting expenditures to fit a shrinking tax base in ways that would have enraptured today’s American Republican Party. In 1935 Prime Minister Pierre Laval tried to cut both prices and wages by government authority, measures that added new recruits to the extreme fringes. Budget-cutting as a Depression remedy, even more than the French left’s traditional opposition to military expenditure (which ceased in fact in 1936), also produced a deficit in French military equipment that could not be overcome in every category by 1940, despite strenuous last-minute efforts.

The third challenge, the rise of Nazi Germany, which was bent on overturning the peace of 1918, had the effect of dividing France in two. Was it better to resist Hitler vigorously (thereby favoring the only effective counterpower, the Soviet Union) or make a deal with him and keep the Russians out of Europe? The two totalizing ideologies offered tempting alternatives to the lackluster republic, and their conflict wound all these tensions to a higher intensity. Brown’s chapter on the Paris World’s Fair of 1937, where two towering pavilions—the German and the Russian—confronted each other across the entryway, evokes that split graphically.

Rumors of corruption seemed to heap particular discredit on the French Third Republic. Brown vividly describes the scandals surrounding the financing of the Panama Canal in the 1890s and the financial speculations of Alexandre Stavisky in 1933. Both cases persuaded many French people that Jews were defrauding the public with the complicity of corrupt politicians. When groups of war veterans and Action française militants tried to march in protest on the Chamber of Deputies on February 6, 1934, the police used live ammunition and killed fourteen protesters. It was the bloodiest night in Paris between the Commune of 1871 and the Liberation uprisings of August 1944. It was also a decisive moment in aligning people like Drieu La Rochelle with fascism as the only way to clean up the country. His autobiographical novel Gilles (1939) tells the story of Gilles Gambier, a veteran of World War I, who marries and divorces a rich Jewish woman—one of the many anti-Semitic caricatures in the novel—and later becomes a fascist.

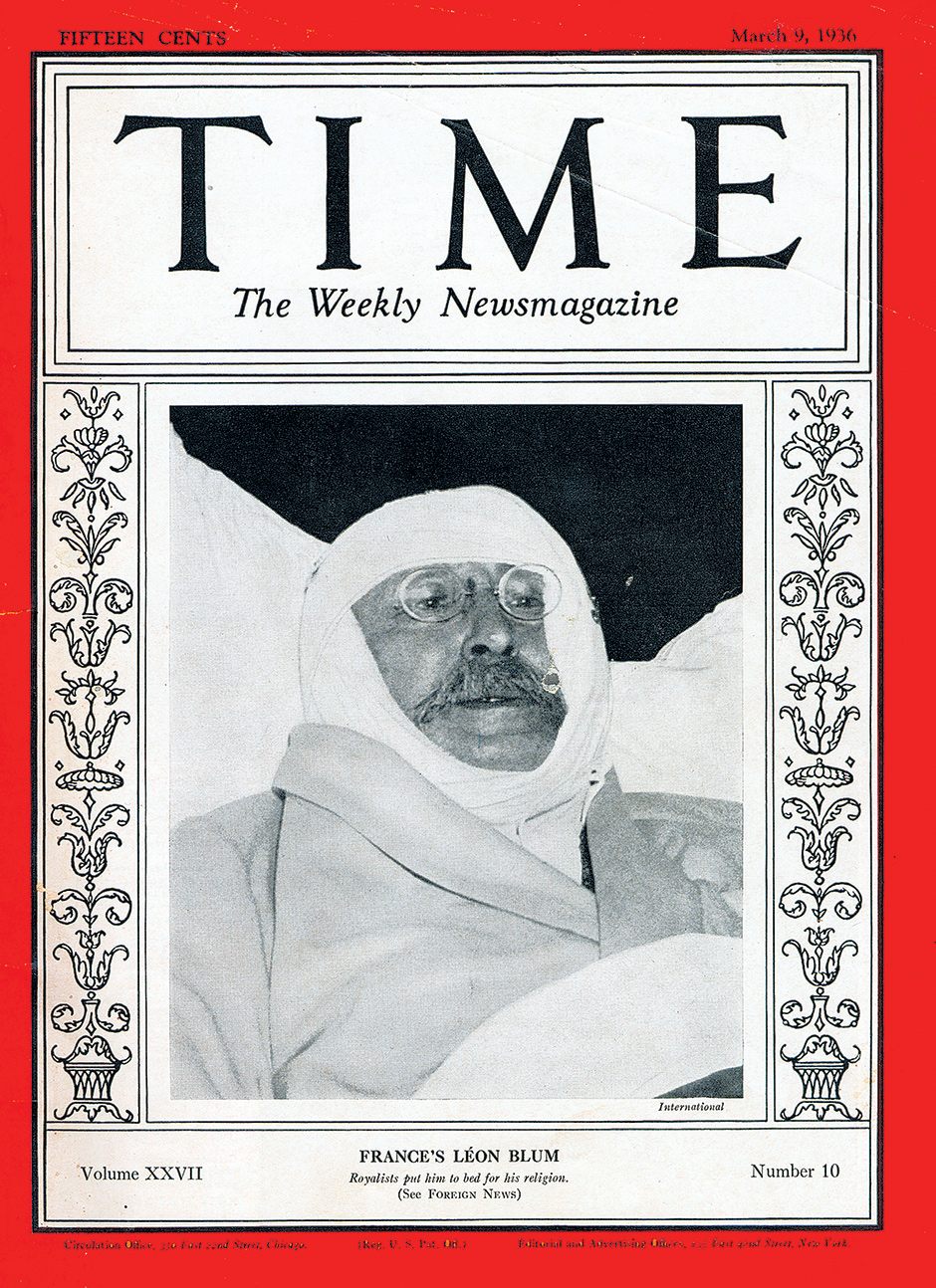

These were signs of France’s crippling polarization in the 1930s. The growth of anti-system parties and movements left little room in the center for moderate compromise. The obloquy that surrounded the Popular Front leader Léon Blum, who became France’s first socialist and first Jewish prime minister in 1936, and a political stalemate between right and left that made it difficult for France either to recover from the Depression or to rearm against Hitler recall eerily Obama’s America. There was even a popular revolt against taxation led by an antigovernment “Taxpayers’ League” (Ligue des contribuables), though Brown does not mention it. The stalemate was all the more severe in France because the French social structure was balanced inconclusively between archaic small farms and small businesses on the one hand and modern business on the other, neither of which could carry the day.

In Frederick Brown’s book it is the intellectuals in the foreground who drive the period, rather than the underlying turmoil that made unreason so plausible. It seems permissible to suspect that these intellectuals did not so much create the doomed interwar decades as undergo them, and rail at the constraints imposed on them, each in his own way.

Brown’s choice of years deserves more explanation than we get. He knows perfectly well that the French embrace of unreason did not begin in 1914 (his well-regarded companion study of the preceding years evokes the conflict between “champions and foes of the Enlightenment”).2 In 1914 the embrace of unreason had already been underway for a very long time. Indeed the Enlightenment generated its own immediate reaction. Friedrich Nietzsche gave the embrace of unreason a decisive new impulse in the 1880s. But Nietzsche’s wide impact in France appears in this book only with Drieu. Barrès had already studied Nietzsche closely, and found much to admire (though not Nietzsche’s German-centeredness).

Another plausible starting point would be 1890, identified by H. Stuart Hughes sixty years ago as a moment of uniquely sweeping intellectual and cultural change: the discovery of “consciousness and society” by, among others, Freud, Bergson, Weber, and Durkheim. One curiosity that Brown mentions but leaves unexplored is why Freud arrived so late in France. André Breton and his Surrealist colleagues discovered the unconscious more in the hospital wards full of shell-shocked soldiers that I have mentioned than in Freud, who was not yet translated into French, as Brown reminds us. And one could go on about the embrace of unreason in France after 1945, but that would be a different story.

Brown’s group portrait, unsurprisingly, is incomplete. Such projects inevitably embody a personal selection. In this case the author has chosen people he disapproves of, as is perfectly legitimate. But other significant French writers and intellectuals did not embrace unreason between the wars. They were in place to lead the remarkable recovery of France during the Trente glorieuses after World War II. The charismatic unifier Charles de Gaulle, ardent democratic rationalists like Jean Guéhenno or the leaders of the League of the Rights of Man, and independent-minded Catholic moralists like François Mauriac and Georges Bernanos all contributed major alternative voices to the time.

A proper frame for the French interwar period also needs comparison with other countries. Did the French embrace unreason more, or less, than other European peoples in this period? The Germans surely went further. This was not surprising in a country whose very national identity had been formed in reaction against Napoleon’s imposition of at least some Enlightenment values by force of arms a century before. Elsewhere in Europe the assault upon Enlightenment values generally came with the fin de siècle. Even in the English- speaking world, Yeats, Pound, and others experimented with “automatic writing” and the occult in the 1920s. We are concerned here with a broad international cultural shift in which French participation may well be seen as relatively late and incomplete.

It would be fruitful, too, to compare this period with other periods of French history. The disastrous interwar years are an anomaly, though people dubious about France might like to think them typical. France’s prosperity in the decades before 1914, its nearly suicidal endurance in World War I, and its spectacular resurgence after 1945 to become the world’s sixth-largest economy, with one percent of the world’s population, are all incomprehensible if the interwar years are seen as the French norm.

How did things go so dreadfully wrong then, after France had emerged nominally victorious, though deeply wounded, from World War I? The question remains. Frederick Brown has given us a stimulating portrayal of one tendency in intellectual and cultural life during the French interwar years. But he would probably concede that much more was going on.

-

1

On this point see the most authoritative historian of the campaign, the German officer-historian Karl-Heinz Frieser, The Blitzkrieg Legend: The 1940 Campaign in the West (Naval Institute Press, 2005), p. 287. Julian Jackson’s The Fall of France: The Nazi Invasion of 1940 (Oxford University Press, 2003) is also excellent. ↩

-

2

For the Soul of France: Culture Wars in the Age of Dreyfus (Knopf, 2010). ↩