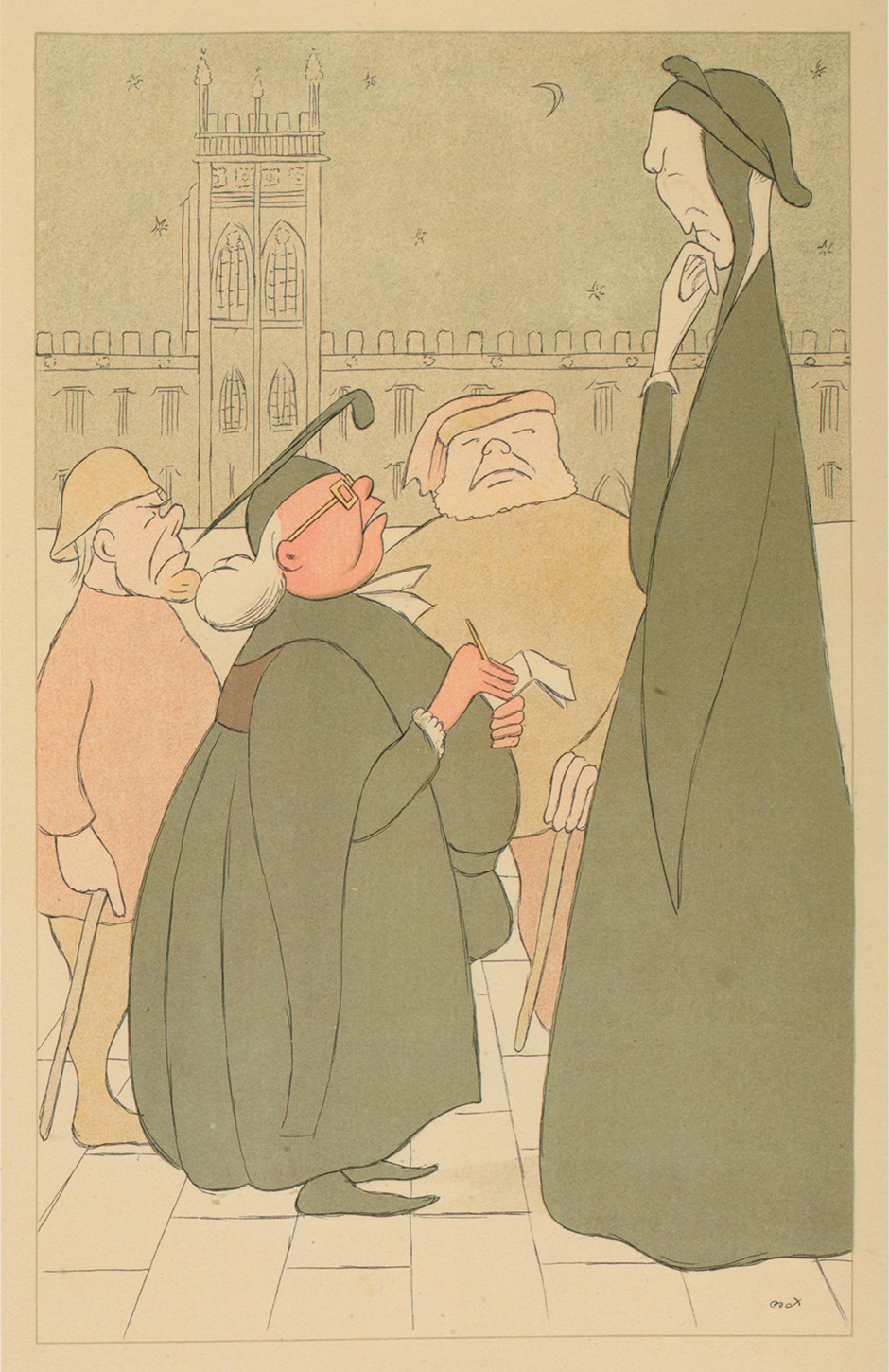

Anyone who frequents research libraries in Europe or North America will know that it is not unusual to encounter in them individuals who appear to be rather introverted and yet sport oddly ostentatious hairstyles, with unkempt shocks of hair sprouting with peculiar abandon from their pallid male scalps. You can still encounter the odd Yeatsian dandy, but the slightly disheveled Einsteinian archetype seems largely to have prevailed in the academy, just as the Beethovenian archetype has long prevailed in the world of music. This phenomenon alone, the slightly embarrassing aping of the superficial attributes of genius, reveals an ersatz quality to the idea of genius we have inherited; even in the most solemn temples to intellectual achievement the notion is awkwardly associated with a good deal that is theatrical, preposterous, ridiculous.

Darrin McMahon’s Divine Fury does not shy away from the preposterous and the ridiculous, or from the disturbing and dangerous. Many of us now use the term “genius” as a simple expression of wonder, referring to a person or an achievement that we find inexplicably brilliant. But as McMahon’s rich narrative shows, across its long history the term has accrued connotations that go far beyond this commonsense core, leading us into the realms of superstition, bad science, and subservience to questionable forms of authority. And yet his book ends on an unexpected note of regret that “genius” in the most extravagant sense of the term has given way to more trivial uses, to a culture in which everyone has a genius for something and where even infants might be “baby Einsteins.” The cult of the “great exception,” the unfathomably and inimitably great human being, he tells us, has justifiably waned. Nevertheless, McMahon’s closing words are elegiac, hinting that its loss might somehow diminish us.

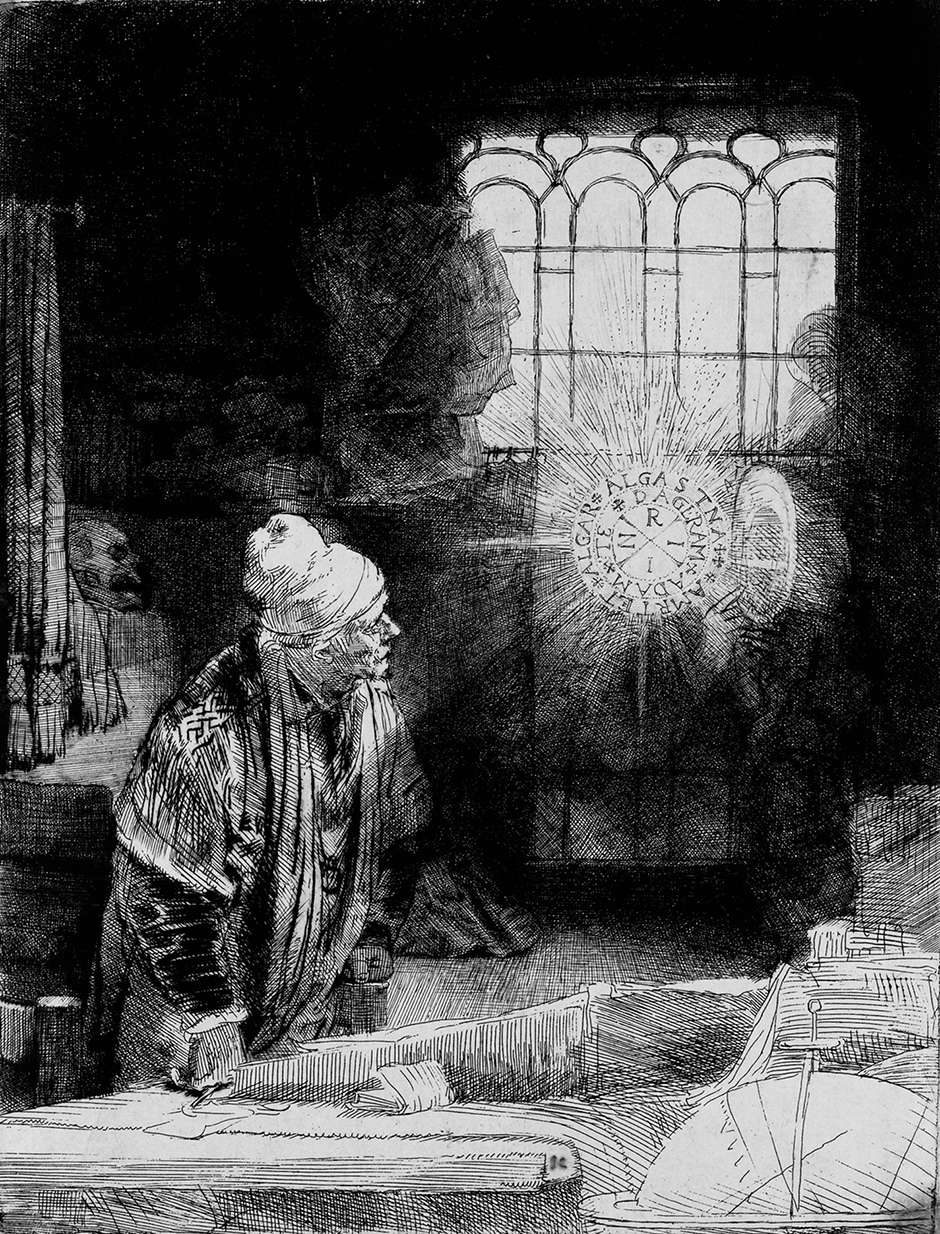

In his intriguing story not only is the age of genius dead; the seeds of its destruction were sown very early on. The term “genius” in its modern sense was first adopted in the eighteenth century and it involved a conflation of two Latin terms: genius, which for the Romans was the god of our conception, imbuing us with particular personality traits but nevertheless a supernatural force external to us, and ingenium, a related noun referring to our internal dispositions and talents, our inborn nature. McMahon also details the associations that these ideas had derived from the Greek world, particularly from speculation about the Socratic daimonion, the Platonic idea that poetry is the product of a “divine madness,” and the Aristotelian view that there are fundamental differences between minds.

So why did the moderns need a term like this, in which natural characteristics are fused with supernatural associations? McMahon’s account is not, as we might expect, rooted in the inexplicability of certain human achievements, the perceived inability to comprehend them in purely natural terms. Rather, he suggests that two fundamental transformations in human thought created the need for such a conception. The first was the process of disenchantment through which God came to seem increasingly remote from human life as belief in his intermediaries among us—spirits, angels, prophets, apostles, and saints—was eroded. McMahon hypothesizes that this created a sense of abandonment, a need for “assurance that special beings still animated the universe.”

The second relevant transformation, he tells us, was the emergent belief, from the seventeenth century on, in the natural equality of all human beings, a belief that provoked as a powerful reaction an insistence that we recognize naturally superior beings. The cult of the genius arose as a response to this dual challenge, identifying a species of being “who walked where the angels and god-men once trod.” In an age in which both secularization and egalitarianism were advancing rapidly, then, the notion of “genius” must have been imperiled from the start.

McMahon’s narrative is not driven by the mysteries of individual geniuses. He waves his hand rather nonchalantly across their ranks:

Geniuses translated, decoded, and deciphered the mysteries of the universe, even as they rendered the universe deeper, more complex, and more profound…. Wonders themselves, they made the world wondrous with their revelations and creations…. Geniuses reassured that the universe was still a magical place.

Their accomplishments are all subsumed in a story of reaction and regression, of which we are called upon to disapprove.

And we are offered a good deal to disapprove of in the detailed and colorful pages that follow: the transformation of the idea that genius consists in a genius for something in particular, manifested in discrete capacities, into the idea of genius as a “unitary constant,” a power that can be applied to anything by its holder; the attribution of a biological basis to this new type of being, “the genius”; the racist exploitation of that myth in Europe and America; eugenics programs, phrenology, and organology (pseudosciences that claimed to prove that genius was the sole province of white males); dictators who exploited the cult of genius to support authoritarian rule.

Advertisement

Some of McMahon’s strongest claims seem rather undersupported by the evidence, for example that “the religion of genius was a precondition of Hitler’s acceptance.” But it is with bold confidence that the narrative draws us inexorably toward its dramatic conclusion, the burning down of Valhalla. The war with the “evil genius” Hitler is ended by atom bombs—an apocalyptic force unwittingly unleashed by the “good genius,” Einstein. The good genius is also the last genius, since his achievements, “however noble,” McMahon tells us, still served in the end “to highlight…the impotence of the individual before ideologically driven masses and the organized violence of states.”

After the war, McMahon writes, shaken nations were reluctant to credit flawed human beings with the superhuman attributes of genius and wary of “investing human idols with such power.” He claims that it is hard to name someone genuinely held to be a genius in the postwar world who is not a holdover from the pre-war period. Or at least, no single figure can “command common and overwhelming assent.” If we still use the term with profligacy for professors and pop stars and Hollywood actors, it is only because it has become so emptied of meaning as to be trivial and harmless, a breathless superlative employed in admiration of any degree of talent.

And yet McMahon seems wistful. The idea of genius, he concedes, “long kept alive an exhilarating sense of the possibilities of being—and being transcendent—in the world.” But if there is a legitimate basis for this regret it is difficult to detect it in McMahon’s debunking historical account. There is more to be said about what these “possibilities of being” consisted of and whether we should feel a sense of loss if they are no longer alive.

Alexander Pope described the achievement of the great genius of the Enlightenment in these famous lines:

Nature, and Nature’s laws lay hid in night:

God said, Let Newton be! And all was light.

The vast darkness of the universe was at last illuminated by the human intellect. Newton’s achievements were felt to have cosmic significance.

The genius, on this understanding, answers the human demand for what Thomas Nagel has called the “yearning for cosmic reconciliation,” that is, for a way of living in harmony (being connected “intelligibly and, if possible, satisfyingly”) with the whole of reality. This is not a demand that has to emanate from within a religious perspective, or one that can only be met by a religious worldview. But nonreligious people who feel this yearning will always be faced with the possibility of absurdity.

Friedrich Nietzsche (who, by the way, had little interest in the concept of genius) expresses this sense of the absurd in his own simple parable:

In some remote corner of the universe, poured out and glittering in the innumerable solar systems, there was once a star on which clever animals invented knowledge. That was the haughtiest and most mendacious minute of “world history”—yet only a minute. After nature had drawn a few breaths the star grew cold, and the clever animals had to die.

This picture of cosmic insignificance is what the idea of genius has repeatedly challenged. The genius has provided us with what we might call a theodicy of the human mind—not the traditional theodicy that tries to justify the ways of god to suffering humanity, but rather one that permits us to see ourselves, in however attenuated a sense, as the point of it all. If we no longer believe in genius in this sense, perhaps that is the result not simply of a social or political shift but rather an intellectual one, a deep change in the way we understand the mind and its relation to the cosmos.

It was among the early Romantics that a secular conception of genius as a theodicy of the mind first took hold. Newton was not, for the Romantics, the prototypical genius, casting light into the darkest corners of existence. The materialist, mechanistic worldview of Newtonian science could not accommodate the most important features of experience, the human mind and human freedom. In McMahon’s story the part played by Romanticism is chiefly that of mystification (he even at one point compares Romantic claims about the realm of Idea or Spirit made by such writers as Schelling, Novalis, and Friedrich Schlegel to the obscure and rambling metaphysics of the occultist Helena Blavatsky, founder of the Theosophical Society). But in fact at the foundation of much Romantic thought was an attempt at demystification, at clarifying the relationship between mind and world. The transcendental idealist tradition in philosophy, founded by Immanuel Kant, gave rise to a notion of genius that unified the human mind and nature in a distinctive way.

Advertisement

In his Critique of Pure Judgment Kant had argued that Newtonian physics could not explain how complex, self-organizing life forms such as plants and animals could come into existence. Human artifacts with complex mechanisms have an external cause, but plants and animals appear to be self-organizing and self-maintaining. Kant suggested that the best way to describe them was as if they were behaving with an inner purposiveness. The “as if” is important: he did not believe we could prove there was an implicit teleology at work in nature, only that it was a necessary supposition once we tried to comprehend those aspects that mechanistic ideas could not explain.

Kant saw the same kind of process in the work of the artist. Beauty in a work of art consisted for him in the ability to stimulate a pleasurable interaction between our understanding and our imagination, a state of free play that could not be captured by any determinate concept. So the creation of a work of beauty could not involve setting out from a concept of what is to be produced and then following rules for its production. A form of unconscious purposiveness had to be at work. “Genius” was Kant’s description of this process: it was “the innate mental aptitude (ingenium) through which nature gives the rule to art.” Artistic genius connected us in a deep way with nature.

The early Romantics seized on the idea of an organism as a means of describing nature not as a machine but as a living force, dropping Kant’s proviso that this is a merely regulative idea. Hölderlin, Schelling, and the Schlegel brothers developed this Kantian conception into an idea of the cosmos as a whole (though an idea that could be properly comprehended not by reason but only by aesthetic intuition). The mental and the physical were understood as manifestations of the same underlying force generating the infinitely complex, self-organizing structure that was the cosmos. Human creativity was continuous with this self-organization but it had a special status as the point at which the whole process achieved self-consciousness. As Schlegel put it, “Man is nature’s creative backward glance upon itself.” And the genius, of course, was at the apex of the entire hierarchy, the most sophisticated and marvelous expression of the force that moves the cosmos.

The German Romantics were therefore committed to the idea that the true genius combines self-conscious reflection with deep unconscious sources of creativity. As Romantic ideas spread across Europe the claim that the role of the unconscious in creation separated the original genius from mere imitators quickly caught on. M.H. Abrams, in his classic study The Mirror and the Lamp, wryly notes: “With the end of the eighteenth century in England, even the more sober poets began to testify to an experience of unwilled and unpremeditated verse.” If nature was working through the mind of the genius, it could contain infinities.

The Kantian concern with the beautiful was eclipsed by his notion of the sublime. This meant to the Romantics the sense that in confronting natural phenomena so immense that our imagination cannot fully picture them, we nevertheless feel the superiority of our own reason; the mind can grasp infinities that our senses cannot show us. Beethoven was the artist who, above all others, conjured this feeling of confronting titanic forces and yet soaring above them, exalted.

If the idea of genius, then, served as a theodicy of the human mind, what of the extraordinary individuals whose intellectual achievements did not exalt us? Charles Darwin, who was responsible for one of the greatest transformations in human self-understanding there has ever been, brought us very much down to earth. And indeed he did not supply a new archetype for genius; in fact there has always been controversy over whether he deserves the title (he is barely mentioned in McMahon’s book). He did not even consider himself a genius: “I have no great quickness of apprehension or wit,” he said.

Darwin saw himself as rather a plodder and marveled that with his “moderate abilities” he had nevertheless managed to influence scientific thought to such an extent. Some of his most important breakthroughs were made during eight years of work on barnacles and after all his tremendous discoveries he spent his final years studying worms. An understanding of our place in nature in purely materialist terms did not seem to constitute an explosion of light in the universe.

Einstein, on the other hand, clearly supplanted Newton in the public mind as the genius who had unraveled the darkest mysteries of the cosmos, revealing that even space and time were not what we had supposed but rather vastly more strange and mysterious. When the theory of general relativity was confirmed by the 1919 eclipse, it was reported in the press as one of the greatest achievements there had ever been in human thought. And Einstein himself described in very Romantic terms the marvelous arrangement of the universe, his faith in the “beauty and sublimity” of the transcendent order that lay behind it all. He expressed wonder that the world as we experience it is not a random jumble of perceptions but is ordered in such a way that we can comprehend it: “The eternal mystery of the world is its comprehensibility…. The fact that it is comprehensible is a miracle.”

It would be an exaggeration to say that no physicist since Einstein has been considered a genius, but what is true is that this faith in the natural harmony of the human mind with a rationally accessible, predictable external order suffered some severe blows from within physics during Einstein’s lifetime. Niels Bohr and his colleagues demonstrated that in a quantum system the location of a particle prior to observation could only be described probabilistically, as a wave function. But once that particle is observed or measured, the wave function collapses, and the particle is found to have a determinate location. In reality as we ordinarily know it, everything has a determinate position rather than occupying an indeterminate “superposition.” The Copenhagen interpretation of the quantum phenomenon by Niels Bohr and his colleagues asserted that the act of observation itself caused the wave function to collapse.

Bohr and Werner Heisenberg, with bitter opposition from Einstein, assailed the assumption that the relationship between the mental and the physical could be modeled as a mind comprehending an objectively existing external reality. Nor did they replace this model with any view that was either compatible with our commonsense understanding of ourselves or reassuring about our place in the universe. And further attempts to solve the measurement problem have generated even more bewildering notions. Hugh Everett proposed that the wave function does not in fact collapse but rather all its possibilities are realized; although we perceive the particle at only one determinate location, there are multiverses, of which we are unaware, in which every other location is perceived. On this Many Worlds view, which hypothesizes billions of parallel universes, our ordinary conceptions of mind and world have become so remote that we can no longer have any sense of what a theodicy of mind would look like.

But there is one field of human thought in which the highest idea of genius still seems to some to make sense. That is mathematics. In the popular imagination mathematical genius now seems to be the dominant model and it is not hard to see why. Not only do mathematical achievements require extraordinary intellectual abilities, unimaginable to nonmathematicians, they also have certainty and permanence. The fallible human mind participates in the beauty of an infallible abstract realm that, in the view of many mathematicians, exists independently of the mental and physical worlds. Kurt Gödel, Einstein’s friend and colleague at the Institute for Advanced Study in Princeton, took this kind of mathematical Platonism to be a consequence of his First Incompleteness Theorem. He proved that for any finitely specifiable, consistent formal system of sufficient complexity to express arithmetic, there will exist truths of arithmetic that are not provable within that system. Gödel inferred from this that it was impossible to think of mathematics as a human construction.

That position is philosophically controversial but it allows us to imagine possibilities for a new theodicy of mind based on the mathematical model. The phenomenon that Eugene Wigner, in his 1960 paper, called “The Unreasonable Effectiveness of Mathematics in the Natural Sciences” expands our sense of living in a universe designed somehow to be intelligible to us. But for those who believe in this possibility, it is an article of faith. The fact that laws of physics can be expressed (revealed to us) through mathematical concepts, such as complex numbers, which are not derived from any experience of the world, is mysterious to us. And the fact that the human mind has evolved in such a way that it can recognize these utterly unintuitive mathematical truths is equally mysterious. We are very far indeed from developing a coherent and persuasive theory of how the mental, the physical, and the “third realm” of abstract objects, such as mathematical results, might all be related, explaining the miracle of comprehensibility.

If we were to do so, elevating the human mind once more to the status of being a central structuring principle in the cosmos, this would constitute a form of idealism that goes against the prevailing assumption among natural scientists and philosophers that any explanation of the natural order must ultimately have a physical basis. But unless physicalist naturalism succeeds in explaining how the cosmos can contain conscious creatures for whom the universe is intelligible, there will be those who hold out hope of an alternative. Thomas Nagel, one of the few philosophers today holding onto such hope, implies that we in fact have an ethical obligation to understand our deep relation to the cosmos, because “in each of us, the universe has come to consciousness.” As Schlegel said, we are nature looking back at itself. But many more geniuses would be required for us to uncover what this really means.

In the meantime, if the mathematical paradigm seems too abstract, too remote from our lived experience, we have found an artistic genius to make that abstract order resound with human emotion. Johann Sebastian Bach is the musical genius of our age. Not the Bach of the Mass in B Minor, though, or the Saint Matthew Passion. Undoubtedly we still admire those tremendous choral works, but it is the instrumental works, and the keyboard works in particular, that have been chosen to communicate our secular theodicy of the mind. The formal qualities of these works, the internal logic of counterpoint and harmony, are dazzling. But at the same time they somehow express authentic human emotions. Objective abstract order and subjective human experience are mysteriously in harmony.

Glenn Gould drew attention to this aspect of Bach in the sleeve notes to his first recording of the Goldberg Variations in 1956. The work ends where it began, with the original sarabande. Gould tells us that “its suggestion of perpetuity is indicative of the essential incorporeality” of the work. He notes its “disdain of the organic relevance of the part to the whole,” and yet “without analysis we have sensed that there exists a fundamental coordinating intelligence.” What is achieved is a “union of music and metaphysics” in the “realm of technical transcendence.” And yet the aim of the work, he tells us, is “a community of sentiment.” Profound and noble emotions are inscribed in the work’s formal properties.

Douglas Hofstadter has gone as far as to suggest that some of Bach’s formal devices, mirroring Gödelian self-reference, provide the key to understanding how consciousness could have emerged from the physical world. And Carl Sagan, when consulted about the music that should be sent in the Voyager I space probe to regions where it might reach extraterrestrial intelligence, responded:

I would vote for Bach, all of Bach, streamed out into space over and over again. We would be bragging, of course, but it is surely excusable to put on the best possible face at the beginning of such an acquaintance. Any species capable of producing the music of Johann Sebastian Bach cannot be all bad.

Bach, it seems, has kept alive for a few the faith that genius might vindicate the human mind from the perspective of the universe.

As the little Voyager I spacecraft began its long journey into interstellar space, the probability that the tiny creatures left behind on earth would obliterate themselves in a nuclear holocaust was not vanishingly small. This outcome would have made even the Goldbergs moot. The nuclear catastrophe was averted but our astonishing capacities for imagination and invention have allowed us to discover new means of total self-destruction. Sir Martin Rees has predicted that we have no more than a fifty-fifty chance of getting through the next century without a catastrophic event. We are relentlessly destroying the only known life-supporting planet in our solar system. The human mind may yet render itself absurd without any help from the cosmos.

So perhaps it is no wonder that for many individuals their theodicy has shrunk to the proportions of the nursery, to an infant watching brightly colored toys on a screen accompanied by Bach’s Cello Suite number 1, arranged for xylophone and electric keyboard. Our “baby Einsteins,” every one of their emerging minds a miracle, justify to their parents all of conscious human existence. We must hope they can find new “possibilities of being” for themselves.