1.

Paul Taylor of the Pew Research Center argues that surveys of public opinion are both necessary for democracy and based on equality. His The Next America opens:

Opinion surveys allow the public to speak for itself. Each person has an equal chance to be heard. Each opinion is given an equal weight.

This view has long been held in the survey industry, going back to the early days of George Gallup, who called polls “the pulse of democracy.”1 Some recent books on surveys show how they can help us understand American society, so long as we are aware of their limitations. For example, Taylor tells us he found that 39 percent of Americans agree that “marriage is becoming obsolete.” But are we hearing “the public…speak for itself”? Certainly many people have changing views about the state of marriage but it’s hard to believe that so many were calling it “obsolete” before an interviewer introduced the word.

Still, many of the Pew Center’s findings shed light on where the country is moving. Thus Taylor reports that support for legalizing marijuana has gone from 12 percent in 1969 to 52 percent in 2013. We also learn that even among people in their fifties and sixties, only 50 percent still feel that the United States is “the greatest country in the world.” In 2012, Pew put the following question to 3,008 adults: “Would you say that most people can be trusted or that you can’t be too careful when dealing with people?” Of those responding, trust gets only 37 percent, with 59 percent counseling vigilance. (I’m still musing about what my own choice would be.) So it remains to consider how public views on marriage and marijuana meld with those on personal trust and national eclipse. The Next America works best as a sourcebook, leaving it to others to put the pieces together and try to understand the cause of changes in opinion.

Occasionally, Taylor missteps. For instance, he says that, since 1980, the divorce rate has been declining. That’s true by official tallies. But since they stay single longer, most people now have intimate interludes and then breakups that resemble what were formerly divorces. Apparently something is being learned from such experiences: recorded marriages are becoming more stable.

Taylor’s summary chapter barely mentions surveys. He titles it “The Reckoning,” by which he means confronting the costs of an aging population. In his view, strict limits must be set on medical treatment for the elderly. To further tax an already “hard-pressed young” can only undermine the nation’s “economic vitality.” In turn, older people shouldn’t expect more to be spent on them as their time arrives. Even now, we have $1,000 pills, courtesy of a medical-industrial complex based on churning out putative wonders. Taylor’s proposal will have to mean denials of care, when it is deemed too costly or only marginally helpful. This sounds realistic but how many people will say they agree in general—but not when it comes to their own mother? I’d like to see how he would phrase a survey question on this issue. Would he present “rationing” as an option? As people are living longer, at what age would rationing start?

The General Social Survey (GSS), a private organization, has been posing questions since 1972, and some of its more interesting findings are in Social Trends in American Life. Generous funding from the National Science Foundation allowed it to sample some 50,000 adults on their “values, self-assessments, and behaviors,” as well as “social connectedness, and individual well-being.” Thus we learn that “liberalism” on homosexuality has increased by 73 percent since 1974, while support for abortion has declined by 6 percent. The number of voters identifying as “independents” has risen from 27 percent to 43 percent. I suspect the shift is more a matter of self-image than political preference. To say you are a Democrat or Republican implies that a party has you in its pocket, a presumption fewer want made about them.

In a revealing chapter on race, the Harvard sociologist Lawrence Bobo and his colleagues focus on “fraught, tension-filled, and conflictual interactions along the color line.” Thus a GSS question found only 12 percent of white respondents supporting “preferences” in hiring and promotion of blacks. Another question asked:

What do you think the chances are these days that a white person won’t get a job or promotion while an equally or less qualified black person gets one instead?

Here 67 percent of the whites who were interviewed felt this was somewhat or very likely, probably with some musing that such lamentation could happen to them. This is plainly so in college admissions cases, where white plaintiffs claim they were denied places they had earned. That those suing had been at the bottom of the white list—of course, such lists exist—shows who pays most for affirmative action.

Advertisement

At the same time, in a span of eighteen years (1990 to 2008) the number of whites willing to say their own race is natively more intelligent has fallen from 56 percent to 24 percent. In part, this may be cautiousness about what one says aloud, even to anonymous interviewers, even in “private,” an increasingly unreliable setting. Even so, the authors hope that insofar as “racial stereotyping” is moving from “biology to culture,” this is a “more porous and potentially modifiable stance.”

Since 1973, confidence in “medicine” has declined from 54 percent to 40 percent. Support for the banking industry has been mercurial, at 42 percent one year and 12 percent another. The GSS asks people how happy they consider themselves to be (“pretty,” “very,” “not too”). The proportions of men and women who said “very” are just about identical, at 30 percent and 31 percent. But marital status makes a difference. Of those currently wed, 40 percent declare they are very happy, while only 20 percent of those formerly or never married feel able to say they are.

Are we becoming smarter or dumber? As a surrogate for IQ, the GSS gives a vocabulary test. Respondents are shown ten words, each with five possible definitions. I was surprised to learn that the proportion of correct replies has stayed essentially unchanged: inching from 64.9 percent in the 1970s to 65.7 percent in 2000–2008. But Social Trends in American Life does not let us know the words. A note cites a previous test with twenty words, which I’ve given below.2 The GSS intimates that half of them are in the current quiz, but won’t say which ones. Even when we consider the easiest ten—among them chirrup and solicitor, for example—the proportions who got the meaning right are quite impressive.

2.

For an unabashed indictment of surveys, there is George Beam’s The Problem with Survey Research. “The flaws of polls,” he writes, “are so extensive and severe that survey research, as a method for finding out what’s really going on, should be abandoned.” For one thing, “respondents lie” or “do not have relevant and correct information.” For another, “question wording skews results.” Those who sponsor research “disguise, or hide” its “actual or primary purpose.” Even location matters. The answers given in classrooms differ from those given in dormitories, even when both are anonymous. Beam’s advice: “If you want to find out what’s really going on, don’t ask.”

While spirited, his book isn’t easy to read. It is short on numbers—after all, surveys generate statistics—but is long on listing writers who support what he says. (He cites several comments of mine, all from these pages.) Still, the issues he raises are important, for example whether people respond truthfully. On actual lying, a classic test was conducted in Denver over a half-century ago. A sample of residents was asked if they had an active public library card. The names of those saying that they did were checked against the city’s list. Fully 9 percent weren’t there. When also asked if they had donated to Denver’s community chest that year, 34 percent who said they had in fact hadn’t.3 But the problem isn’t always lying. Last year, the SAT asked 1,660,047 high school seniors for their parents’ income. Most obliged, with 38,887 choosing the $120,000–$140,000 interval. But how many teenagers know that accurately what their parents make? Statisticians call this pseudo-precision.

Surveys assume a certain level of knowledge, at least on the subjects they inquire about. In March, Reuters reported on a poll that it conducted regarding Comcast’s bid to absorb Time Warner Cable. It said it found 52 percent saying that a merger would diminish competition, while 22 percent felt it would bring better service. However, the poll assumed that fully 74 percent of adult Americans know enough about this quite complex transaction to have formed judgments about it. This seems too good to be true, given what we know about how far people follow the news.

Still, opinions can and should be taken seriously even if they’re not accompanied by information. I doubt that even a third of Americans can locate Ukraine on an unmarked map; yet some are already telling polls they don’t want their country involved there. The point, of course, is that they have a definite opinion: it may express a generally reluctant view about policing the world. In this vein, the Reuters survey shouldn’t be seen as being about Comcast, but a concern that corporations are becoming too big. I’ve found that most polls can expand our understanding, even if it’s not about what’s in the headline.

Needless to say, how questions are phrased influences the responses they elicit. People are more likely to support abortion when asked if they feel it should be “legal” than if it should be “available.” Nor is this inconsistent, since legality and availability have different connotations. I’m happy to have both surveys, since together they provide pieces of a larger story. Another poll found that 70 percent would allow doctors to “end a patient’s life by some painless means,” but only 51 percent would let them help a dying patient “commit suicide.” Such variations in phrasing help us gauge the intensity and structure of people’s thinking. And when there is a wide variety of options on an issue, more people will choose ones nearer the middle.

Advertisement

The first challenge for any survey is to secure a reliable sample, which replicates “the frame of all units in the population.”4 For a national poll, about three thousand carefully culled names representing a range of groups will usually suffice; but you’ll need more if you want to separate out, say, the opinions of widowed men. The ideal is a truly random drawing, like having access to Social Security’s master list, and flagging every thousandth name. But since this is not possible, the method of choice is an “area probability sample,” which the General Social Survey and the National Center for Health Statistics both use. First, a representative group of counties is selected, and within them a set of “primary sampling units,” like city blocks or rural tracts. Interviewers usually then get free rein to find respondents within their assigned areas. A well-chosen sample will include a distribution of conventional groupings like races and classes and regions. Another virtue of random drawings is that they bring in spreads of less visible categories—like sadists, introverts, and straying spouses. If desired, a sample’s percentages of, say, college graduates can be checked against census records. Also, some members of a sample may have their responses weighted. If a poll is short, perhaps, on Asians, then each one surveyed may be tallied as, say, 1.2 persons.

In the early days of surveys, interviewers rang doorbells and chatted face-to-face. Then came telephone calls, keyed to street addresses and neighborhoods. Now cell phone numbers are chosen by a computer—a kind of randomness—but not all who pick up are willing to talk. The Internet is being explored, with a full awareness of its hazards. It might be that someone with dementia is responding, it might be a teenager in Riga.

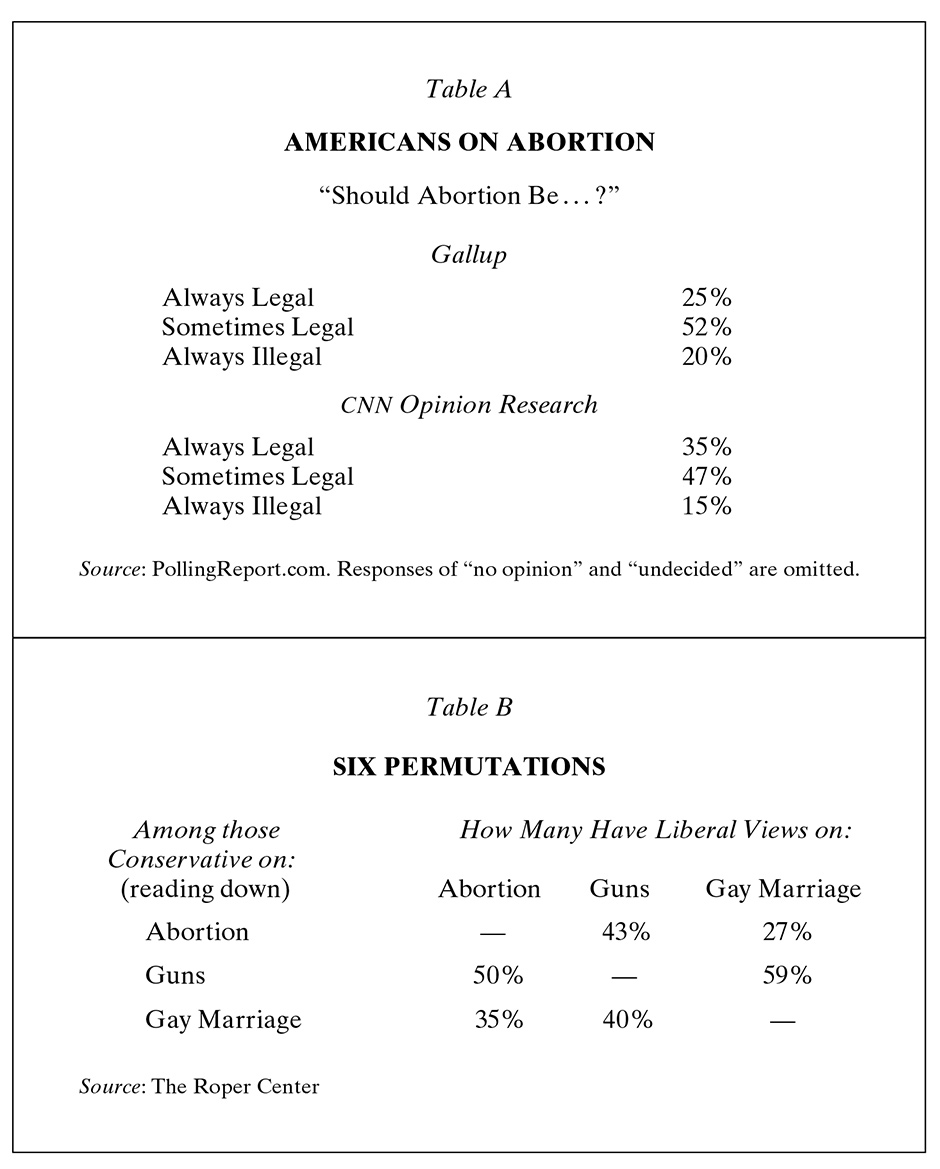

In recent elections, polls have called the vote within one or two points, which means that their samples must have been good replicas of the electorate. But in the case of opinions as distinguished from voting choices, there is no way to verify survey findings. If most Americans have views on abortion, there isn’t an official register showing the variations. Hence recourse to polls, two of which I cited in an earlier article.5 Both began, “Should abortion be…” and then offered identical options. Table A presents the results.

Since Gallup and CNN used their own samples, it’s not surprising that their results differ. But what is striking is how close they came. Splitting the difference, I’m willing to put the “always legal” view at about 30 percent, give or take, and “always illegal” around 17 or 18 percent.

The census is also a survey, even if it tries to include everyone. For its basic questions, it aims at a 100 percent response, via mailed forms or personal visits, if the forms don’t come in. In 2010, it estimates that it found 97.5 percent of all persons then living in the country. Still, like polls, it must rely on what people tell them: about their age, ethnicity, who owns their current residence, and whether any of their offspring are stepchildren or adopted. (The most recent compilation is for 2010, where of all 88,820,256 children, 6,238,198, or 7 percent, were reported to be stepchildren or adopted.)

On how it deals with the 2.5 percent who won’t answer doorbells or seem never at home, the census prefers something called “imputation.” That is, it creates fictional counterparts of the people it can’t find, endowing them with attributes common in the surrounding area. Like their race, or even having a stepchild. These fictions are said to be necessary, because an apparent full count is needed for creating congressional districts

3.

An acid test of surveys arises when questions get very personal. One such survey is from the National Center for Health Statistics entitled Sexual Behavior, Sexual Attraction, and Sexual Identity in the United States. It takes its title literally, posing explicit questions on all three topics. To encourage truthful replies, it employed “audio computer-assisted self interviewing,” wherein “the respondent listens to the questions through headphones, reads them on the screen, or both, and enters the response directly into the computer.” Interviewers need do little more than open the laptop. A total of 13,495 men and women obliged, a very adequate sample. (For example, teenagers comprised 18.8 percent of the sample, compared with 16.9 percent of the actual population.) Here are some questions that appeared on their screens:

• Has a male ever put his penis in your rectum or butt (also known as anal sex)? [to women and men]

• Have you ever performed oral sex on another female?

• Thinking about your entire life, how many female sex partners have you had? [to women and men]

Among those currently single, 9.9 percent of the men said they had at least four opposite-sex partners during the past year, while only 5.5 percent of the women listed that many. Similarly, of those currently married, 3.9 percent of husbands, but only 2.2 percent of wives, said they had more than one partner in the past year. People who study sex say that men are more apt to exaggerate, whereas women understate, even to a computer. Also affecting the equation is how much of the reported (or unreported) sex is purchased. The only figures on this I’ve seen are in another NCHS survey that asked people if they had had “sex in exchange for money or drugs” in the last year. (An odd question, conflating two kinds of transactions.) Only 1.3 percent of the men said they had. But the 0.7 percent of women who said so might be closer to a (sad) truth.6

In other matters, people seem quite forthcoming. All told, 44 percent of the men and 36 percent of women said they had had anal intercourse with the opposite sex, another gender imbalance, albeit less pronounced. Also, among those under twenty-five, over three times as many women—13.4 percent to 4 percent—admitted to same-sex experiences, a marked gender gap. Even so, 93.7 percent of women and 95.7 percent of the sampled men declared their “identity” to be heterosexual. Another question, this one on “behavior,” found a suspiciously small 1.4 percent of men and 1.9 percent of women saying that most or all of what they did was with same-sex partners. These low figures suggest a severe gay undercount, which shouldn’t occur with so large a sample and the presumed anonymity of the survey.

4.

My own view is that surveys are at their best when they yield new, even unexpected, information. To this end, I asked the University of Connecticut’s Roper Center to collate for me responses on three topics—abortion, guns, and gay marriage—but with a twist. I wanted to know where those with views on each of the issues stood on the other two. Table B gives those results.

So far as I know, permutations like these haven’t been run before. Here, as elsewhere, surveys provide precision, even with margins of error. Common sense, for all its virtues, will not produce 43 percent or 27 percent. Here I’d add that survey findings can prompt reassessments of what we thought we knew. To learn that at least half of gun proponents are liberal on gay marriage and abortion suggests they regard all three as personal freedoms. Posters in favor of “choice” at a gun show are not an outlandish idea. But it’s not as easy to connect why so many who oppose abortion and gay marriage also want to limit guns. Here, as elsewhere, surveys should be supplemented by Studs Terkel’s kind of colloquy. He would find some Right to Life adherents and ask them how they felt about the Second Amendment. It should be clear that deeper inquiries into the sources of personal views are needed if they are to be adequately understood. But how can intensive interviews be related to broad statistical results? This is still a central question for opinion studies.

Do “surveys allow the public to speak for itself,” as Paul Taylor intimates? Not literally, since we only hear from selected samples, even if randomly drawn. Nor can it be said that people “speak” on surveys, if they are choosing from options others have framed. Yet inherent in Taylor’s view is that survey findings should carry greater weight in the public sphere. As matters stand, officials hear from only a slice of their constituents, and often accord them more attention, as is clear with gun owners. But surveys reveal a full range of views, “the same noble ideal that animates our democracy.”

There’s nothing wrong with legislators having poll results on their desks. But enacting statutes is real work, with bills running to hundred of pages. Foreign policy is no less abstruse, given all the cables and memos. The Columbia political scientist Lindsay Rogers probably had the last word sixty-five years ago, in his still-delightful book called The Pollsters. “The pollsters,” he wrote, “overlook the really vital role of representative assemblies.” Even allowing for alarming exceptions, elected officials are better versed in the legislative art than a sampling of their constituents, who will still have the final say on Election Day. And with more direct participation, as in town meetings, Rogers adds that a “proposition under debate could be reframed to meet objections that the discussion had brought out.” Does Paul Taylor really want governing given over to a population at home in their pajamas when the phone rings?

This Issue

October 23, 2014

How Bad Are the Colleges?

Find Your Beach

Law Without History?

-

1

George Gallup and Saul Rae, The Pulse of Democracy (Simon and Schuster, 1940). ↩

-

2

John B. Miner, Intelligence in the United States (Springer, 1957). His list: accustom, allusion, animosity, blunt, broaden, caprice, chirrup, cloistered, concern, edible, emanate, encomium, lift, madrigal, pact, pristine, sedulous, solicitor, space, tactility. ↩

-

3

Hugh J. Parry and Helen M. Crossley, “Validity of Responses to Survey Questions,” Public Opinion Quarterly, Vol. 14, No. 1 (Spring 1950). ↩

-

4

J. Michael Brick, “The Future of Survey Sampling, Public Opinion Quarterly, Vol. 75, No. 5 (2011), p. 874. ↩

-

5

“How He Got It Right,” The New York Review, January 10, 2013. ↩

-

6

HIV Risk-Related Behaviors in the United States Household Population Aged 15–44 Years: Data from the National Survey of Family Growth, 2002 and 2006–2010, National Health Statistics Reports, No. 46 (January 19, 2012), p. 13. ↩