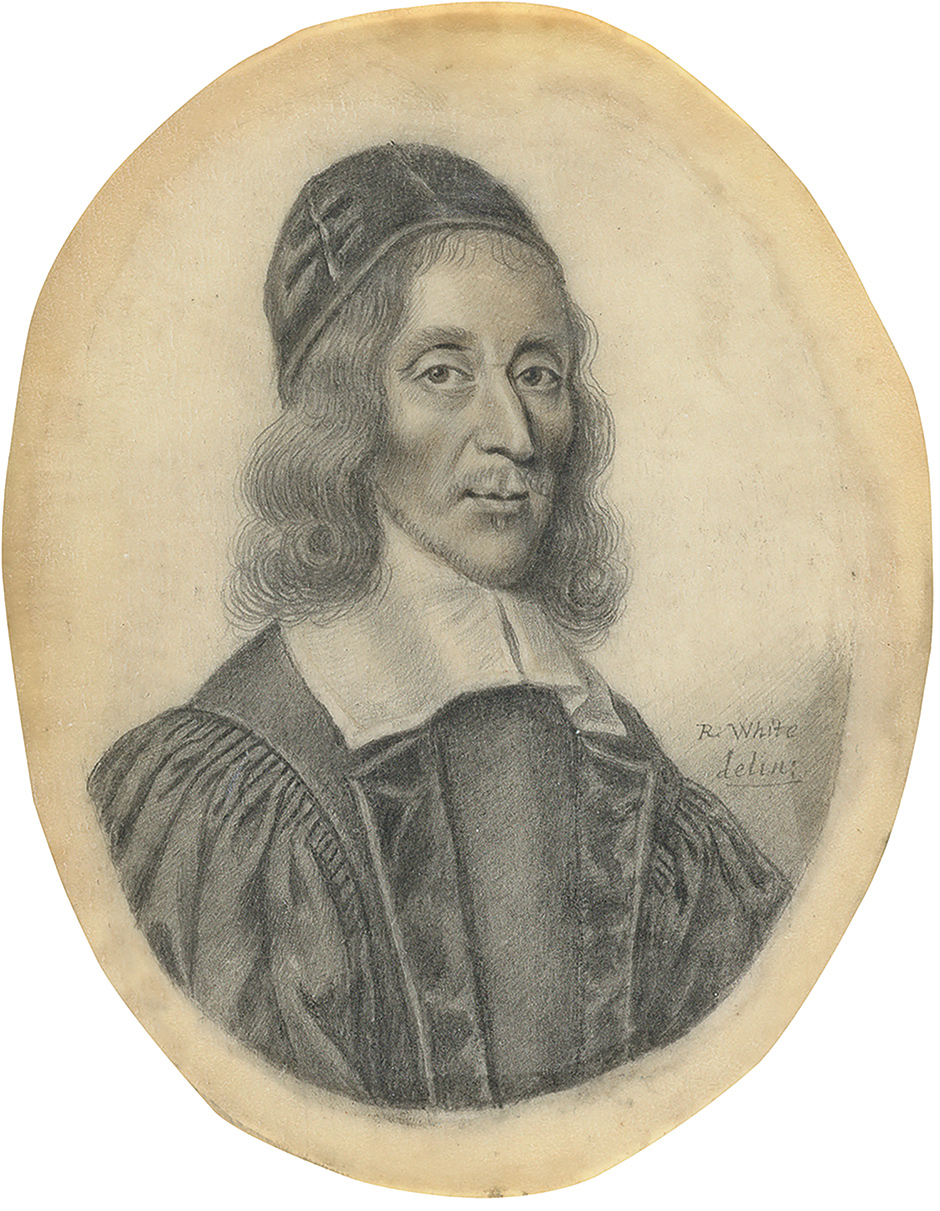

George Herbert is among the best-loved English poets, and he is singular in that he is valued as much for his personality—his humility, gentleness, and holiness—as for his poetry. In this respect he is the polar opposite of, for example, Shakespeare, who is valued solely for his poetry, since we know nothing about his personality. Herbert himself did not, it seems, think of himself primarily as a poet. There is no evidence that he circulated his poems in manuscript among his acquaintances, as his friend John Donne did, nor did he have them published in his lifetime. On his deathbed—in 1633, at the age of thirty-nine—he described them as “a picture of the many spiritual conflicts that have passed betwixt God and my soul,” and asked that they should be burned, unless it was thought that publication of them might “turn to the advantage of any dejected poor soul.” His friend Nicholas Ferrar evidently did think just that and published them later in 1633 under the title of The Temple.

John Drury, Herbert’s new biographer, is, like Herbert, an Anglican clergyman, though from a higher branch of the church. Herbert became, three years before his death, parson of two small Wiltshire villages, Bemerton and Fugglestone, whereas Drury has been dean of two great British educational institutions, King’s College, Cambridge, and Christ Church, Oxford. His book is presented as the culmination of a lifetime’s devotion to Herbert, but it is not a wholly endearing portrait, and may upset those who are used to the Herbert of the poems.

As a family the Herberts were inordinately conscious of their noble rank and the privileges it entitled them to. George’s elder brother, Edward Lord Herbert of Cherbury, left behind him an autobiography that is comically boastful even by the standards of a seventeenth-century English aristocrat. In it he relates how, when he was in doubt whether to publish his philosophical treatise Of Truth, he asked for a sign from God, and the Almighty obliged with “a loud though yet gentle noise from the heavens.” Perhaps it was God laughing. George shared his brother’s self-importance. His first biographer, Izaak Walton, who usually avoids any hint of adverse criticism, acknowledges that as an undergraduate at Trinity College, Cambridge, Herbert kept himself “at too great a distance” from his “inferiors,” and showed by his clothes and manners that he “put too great a value on his parts and parentage.”

In Drury’s estimate young Herbert was a prig as well as a snob. As a teenager he composed two sonnets, addressed to his mother, in which he disparages love poets and vows to dedicate his own poetic gifts to the service of God alone. Unlike Donne and his admired Saint Augustine, Herbert does not seem to have felt the temptations of the flesh very sharply, so his scornful view of sexual love risks seeming facile as well as sanctimonious. His mother was the only woman in his life until, three years before his death, when he was on the point of moving into his country parsonage, his friends and relatives fixed him up with a wife, Jane Danvers. Drury quotes the mischievous raconteur John Aubrey to the effect that she was “a handsome bona roba”—that is, a sexually robust woman—and that being married to her hastened Herbert’s death.

This is probably just spiteful gossip, but it suggests that contemporaries found the idea of Herbert entering into a marital relationship rather incongruous. Drury objects to the anti-love sonnets as gratuitously nasty as well as priggish. Their autopsy approach to female beauty (“Open the bones, and you shall nothing find/In the best face but filth”) strikes him as “distinctly and unnecessarily unpleasant.”

Other faults he identifies in Herbert are irresolution, habitual discontent, and idleness. He planned to study theology, but then decided it was a futile speculative exercise, like astronomy, so gave it up. He lobbied to be elected public orator at Cambridge—a post that might have led to government employment. But once elected, he found the sophistry and flattery the job entailed distasteful, and left the work to his deputy. With Nicholas Ferrar he undertook the restoration of Leighton Bromswold church in Huntingdonshire, close to Ferrar’s community at Little Gidding. But in the event the business of restoration devolved upon Ferrar; Herbert was hardly ever there.

For the seven years prior to his installation at Bemerton, Drury finds, Herbert just “drifted about” as a guest in the great houses of his friends and relations. Though it is impossible to date his poems with any accuracy, it seems that it was in these years that he takes to lamenting having nothing to do, and wishing to be an orange tree—“that busy plant”—because orange trees bear blossom and fruit at the same time, and he bears nothing.

Advertisement

To an impatient reader Herbert, in this mood, can seem like one of the idle rich complaining about being idle and blaming God for it. But that is far from Drury’s purpose. His biography, though sometimes critical, is deeply sympathetic. He encourages us to see that Herbert was far too intelligent not to realize how unreasonable his complaints were. That realization was precisely what made his depression so overwhelming. He argues with God and argues with himself, but all his arguments end with his knowing that he is in the wrong. The poems are about the mind’s struggles and self-torments as much as they are about religion, which is perhaps why, as Drury notes, they are dear to readers who are not in the least religious. One of his greatest poems, “The Flower,” recaptures the moment when depression lifts and life floods back—“I once more smell the dew and rain.” The words seem as unremarkable as breathing, yet they stay in your mind.

It is not, though, only Drury’s psychological perception that distinguishes this biography. His scholarship allows him to illuminate Herbert’s early intellectual history, particularly his classical studies and his mastery of rhetoric. A tour de force is the analysis of Herbert’s rhetorical strategy in his university oration that greeted Prince Charles, the future Charles I, back from his abortive attempt to find a royal bride in Spain in 1623. Herbert, Drury shows, succeeds in seeming not to blame Charles and the royal favorite Buckingham for their farcical Spanish adventure, while tactfully dissociating himself from their demand that King James should go to war with Spain to avenge their hurt feelings.

An anomalous aspect of Drury’s book is that the biographical and literary-critical parts of it seem to be written with different readers in mind. The biographical part assumes a readership academic enough to take an interest in Herbert’s Latin poetry and the “lavish complexity” of his Latin prose. But the literary-critical part is adapted to readers who start out with no prior knowledge of poetry or, indeed, of Christianity. Drury explains in the opening pages that the Bible is not a single book but a collection of books. Anyone likely to read a work about George Herbert might be counted on, you would have thought, to have noticed that already. He also explains that “the technical terms for various metres in poetry look formidable but denote simple things.” Iambics go “ti-tum,” trochees “tum-ti,” spondees “tum-tum.”

Of course, attempting to introduce new readers to poetry is entirely laudable, but those who already have some understanding of the basics may find such instructions irksome, especially when Drury’s standard procedure in discussing each individual poem includes an explanation of how the iambics, trochees, and spondees fit together in it. Herbert was a musician and a composer as well as a poet, and the subtleties of his rhythms cannot be conveyed by wooden attempts at scansion.

While attending to matters that readers might be expected to work out for themselves, Drury tends to skate over real difficulties. He persistently remarks that Herbert’s poetry is “simple,” but the truth is that its simplicities are laced with near-insoluble complexities, as if to remind us, from time to time, that a formidable academic brain is operating behind the country-parson camouflage. Drury repeatedly fails to note these difficulties.

The last two lines of “Affliction” are a case in point. After a series of rebellious outbursts against God’s inconsiderate demands, the poet caves in and submits: “Ah my dear God! Though I am clean forgot,/Let me not love thee, if I love thee not.” There has been much debate about what the final line means. William Empson, in Seven Types of Ambiguity, famously paraphrased it as “Damn me if I don’t stick to the parsonage.” Drury, while leaving Empson’s flippancy unremarked, gives no inkling of how he would interpret the line himself. The same goes for other conundrums that generations of undergraduates have scratched their heads over. What do the words “something understood” mean at the end of the poem “Prayer,” for example? What does “the rest” mean in the last line of “The Answer”? Drury says it “might mean all sorts of things,” but that is hardly a satisfactory critical conclusion.

His praise for Herbert’s poetry tends to ignore its failings. Herbert’s vocabulary is limited and repetitive by comparison with that of almost any other English poet, and his visual effects are weak. The poem “Easter,” for example, contains a sacred parody of a love song, sung by a lover to his mistress on Easter morning: “I got me flowers to straw thy way;/I got me boughs off many a tree.” The next two lines tell us that the mistress is really the risen Christ: “But thou wast up by break of day,/And brought’st thy sweets along with thee.” These lines refer to the account of the resurrection in Saint John’s gospel, where the risen Christ leaves his grave clothes in the tomb. The “sweets” that Herbert imagines Christ bringing with him are the “mixture of myrrh, and aloes, about an hundred pound weight” that, according to the gospel account, were placed with Christ’s body when it was wound in the grave clothes. Trying to visualize the naked Christ emerging from the tomb carrying a hundred pounds of spices would obviously be grotesque, and Herbert’s lines do not encourage us to do it. The “sweets” remain at the innocuous level of wordplay, with no visual reality.

Advertisement

The salient features of Herbert’s religious poetry show up most clearly when it is compared with that of Donne, but aside from a passing reference to Donne’s “theatricality” it is a comparison Drury avoids—and one can see why. Donne’s passion immediately makes Herbert seem tepid. Herbert’s struggles are in the past, and end in submission and reconciliation with his savior. Donne typically uses the present tense, his struggles are still going on, and at the poem’s end he still does not know if he is among the saved or the damned—a question that never even occurs to Herbert. Donne fears that the Christian afterlife will not happen at all: “I have a sin of fear that when I have spun/My last thread I shall perish on the shore.” It is impossible to imagine Herbert writing that, and the impossibility brings home Herbert’s comparative irrelevance to our contemporary consciousness.

A poem that illustrates this starkly is “Love (III).” Drury considers this Herbert’s masterpiece, and seems to regard it as a supreme event in world poetry: “Readers may well get the sense that this poem takes them as far as poetry can ever go.” In the poem Herbert records his encounter with a figure he calls “Love,” who is clearly the Christian redeemer, and who invites him to a meal. Herbert politely protests his unworthiness, but Love insists, and the poem ends, “So I did sit and eat.” Drury comments that it is “set in the hall of some substantial household…such as Herbert lived in for most of his life,” and that “it draws on the manners and etiquette expected of guests and hosts.” What does not seem to strike him as at all strange is that the encounter between the soul and God should be figured as a meeting between two courteous English gentlemen. One imagines that it would have seemed perfectly natural to Lord Herbert of Cherbury too.

Richard Crashaw considered himself a disciple of George Herbert, but the two poets are, in fact, as different as two poets could possibly be, and an admirer of one is seldom an admirer of the other. Drury, in his few pages on Crashaw, deplores his “complete failure of taste,” and that judgment will seem wearisomely familiar to Crashaw’s new editor, Richard Rambuss. His witty introduction conducts us through the annals of Crashaw criticism to demonstrate how the poet’s detractors, generally Anglican Protestants, have regularly found him disgusting, perverted, unmanly, and, in a word, foreign—“an exotic Italian import like pasta or castrati,” as one disaffected commentator put it.

He was not really Italian, of course, but his critics thought his poetry was, and they were right to an extent. Crashaw is the only truly baroque English poet, and his aesthetics are those of the Catholic Counter-Reformation, with its cultivation of sensuous excess as a means of mystical uplift. Yet as Rambuss points out, almost all his poetry was written before his conversion, while he was still an Anglican clergyman.

Born in London in 1612 or 1613, he won a scholarship to Charterhouse School where he displayed almost Mozartian precociousness as a poet, writing, as his scholarship required him to, four Greek and four Latin epigrams every Sunday on some theme from the New Testament. The Watt scholarship that he won to go to Pembroke College, Cambridge, carried similar poetic obligations. At twenty-two he published his first book, a collection of sacred Latin epigrams, many of which he later reworked as English poems. Elected to a fellowship at Peterhouse the following year, he became curate at Little St. Mary’s, preaching sermons that, it was said, “ravished more like Poems” and turning the church into a haven of high-Anglican ritual and holy decoration.

He was a painter—a rare thing among English poets—and this no doubt stimulated his glory in the visual. When the parliamentary visitors descended on Peterhouse and Little St. Mary’s at the outbreak of the civil war they reported with horror on the abominations they found there—“two mighty great angells with wings” that they pulled down and destroyed, along with “about a hundred cherubims,” sixty “superstitious pictures,” crucifixes, and “God the Father sitting in a chayer.” By this time Crashaw had fled abroad, first to Leiden, then to Paris, and, having converted to Catholicism, to Rome, armed with a letter of introduction from Charles I’s Queen Henrietta Maria to the pope. He received a minor appointment at the Santa Casa in Loreto, the small stone house, miraculously conveyed from Nazareth to Italy in the thirteenth century, in which the Virgin Mary had reputedly received the annunciation. But within weeks he caught a fever and died, aged thirty-seven.

Rambuss seeks, and finds, some traces of homoeroticism in the poems, but what really captivated Crashaw was female sexual excitement, particularly as experienced by the Spanish saint and mystic Saint Teresa of Avila. She describes in her autobiography how an angel appeared to her in a vision, carrying a long golden dart, which he drove into “the inwards of my bowels,” causing acute pain but also indescribable sweetness. The erotic implications of this encounter inspired Bernini’s famous statue in the Cornaro Chapel, and Crashaw luxuriates in them with hectic fervor in several poems. Teresa kisses the “sweetly killing dart,” embraces her divine visitor, receives “delicious wounds,” and melts, “like a soft lump of incense,” before expiring with “a dissolving sigh.”

This is just the kind of indelicacy that has disgusted conservative critics. But more recently, Rambuss notes, feminists have tended to celebrate Crashaw as a male writer with a female sensibility. That may be over-hopeful, however. Being turned on by imagining female orgasm is not the same as sympathizing with women. Among Crashaw’s secular poems included in Rambuss’s edition is an epithalamion that seems clearly to sanction marital rape, and relishes female resistance as an incentive to male desire. The bride’s “peevish” denials and “melting no’s” should not, the poem makes clear, be taken seriously as deterrents—quite the contrary. She may think that weeping will save her, but her tears will only “sharpen” the bridegroom’s “flame,” and he is advised to drink the “sweet brine” before it dries up.

Bodily fluids—tears, blood, milk—were another of Crashaw’s fascinations. His poem on the Holy Innocents slaughtered by Herod focuses not on suffering or grief but on the aesthetic pleasure of imagining the mothers’ milk and the children’s blood blended together. This lacteal bloodbath becomes, in the next line, a bouquet, as Crashaw wonders whether “heaven will gather,/Roses hence, or lilies rather.” Probably his most notorious poem is the epigram on a text from Luke 11, “Blessed be the paps which Thou hast sucked.” Instead of the infant Christ being “tabled” at the Virgin Mary’s “teats,” she, the poem foresees, will receive from the crucified Christ life-giving blood: “He’ll have his teat ere long (a bloody one)/The mother then must suck the son.”

To William Empson these lines suggested “a wide variety of sexual perversions,” including incest. What they more obviously suggest is vampirism, though neither Rambuss nor any other critic seems to have thought it worth comment. The vampire’s need for human blood to restore his or her strength and beauty seems to be alluded to in Crashaw’s translation of Giambattista Marino’s Sospetto d’Herode, where Satan is the vampire. The fallen archangel, looking toward “the life-breathing air” of earth from the shades of death, “Lifts his malignant eyes, wasted with care,/To become beautiful in human blood.” The haunting second line is Crashaw’s invention—nothing in Marino’s Italian corresponds to it. The vampire’s appetite for blood is startlingly evident, too, in “Our Lord in his Circumcision to his Father,” where God becomes a vampire. Christ, after his circumcision, offers his severed foreskin to God the Father as a sort of bonne bouche—a sample of a more lavish feast of blood that will come God’s way at the crucifixion: “Taste this, and as thou lik’st this lesser flood/Expect a sea, my heart shall make it good.”

To complain, as Drury does, that such effects are indecorous is to miss the point. Their express purpose is to challenge and outrage received notions of decorum and to stimulate a holy rapture that will soar above all such earthbound proprieties. The anonymous author of the preface to Crashaw’s 1646 poems promised that reading them would actually launch you into the air: “They shall lift thee reader some yards above the ground.” Rambuss says the same thing more prosaically when he claims that Crashaw’s poems amount to “the most sustained endeavor among English poets to render—and by rendering stimulate—ecstasy.”

The two courteous English gentlemen who, for Herbert, represent the soul meeting God are precisely the kind of readers that Crashaw set out to shock. His own version of the soul meeting God is rhapsodic and flagrantly indecent. In a poem innocently entitled “On a Prayer Book Sent to Mrs. M.R.” the “happy soul” is a predatory female, hastening to meet her divine lover and “seize her sweet prey” as he rises to meet her, “all fresh and fragrant,” in a “balmy shower/A delicious dew of spices.” Clasping her “heavenly armful” to her “swelling bosom,” she is the active partner, with “power,/To rifle and deflower” her seemingly passive mate in a crescendo of “pure inebriating pleasures” that reveal “How many heavens at once it is,/To have a God become her lover.”

Modern readers tend to respond to Crashaw’s flightier passages with an embarrassed laugh, which prompts the question: Was he deliberately being funny, at least some of the time? Laughter, signifying release from restraint, or glad abandon, goes naturally with rapture. Are the extravagances of “On a Prayer Book” meant to stimulate high, hysterical joy? When in “The Weeper” Crashaw calls Mary Magdalene’s eyes “Two walking baths; two weeping motions;/Portable, and compendious oceans,” are the absurd metaphors designedly comic? Are they a way of releasing from deadening solemnity a religion that proclaims not tears but joy and eternal life? Is the cherub in the same poem whose song, after he has sipped a tear, “tastes of this breakfast all day long,” a little comedian, placed in the poem to raise an indulgent smile? Rambuss’s reference to “a toothsome angelic hiccup” implies that he takes it as a joke, and it would be good to see him pushing the idea of Crashaw’s holy hilarity further.

Meanwhile, having Crashaw’s English poems back in print is refreshing. But given their ties to their Latin counterparts, anyone with a serious interest in Crashaw will need to seek out the second edition (1957) of L.C. Martin’s definitive Poems, English, Latin and Greek of Richard Crashaw.

This Issue

October 23, 2014

How Bad Are the Colleges?

Find Your Beach

Law Without History?