1.

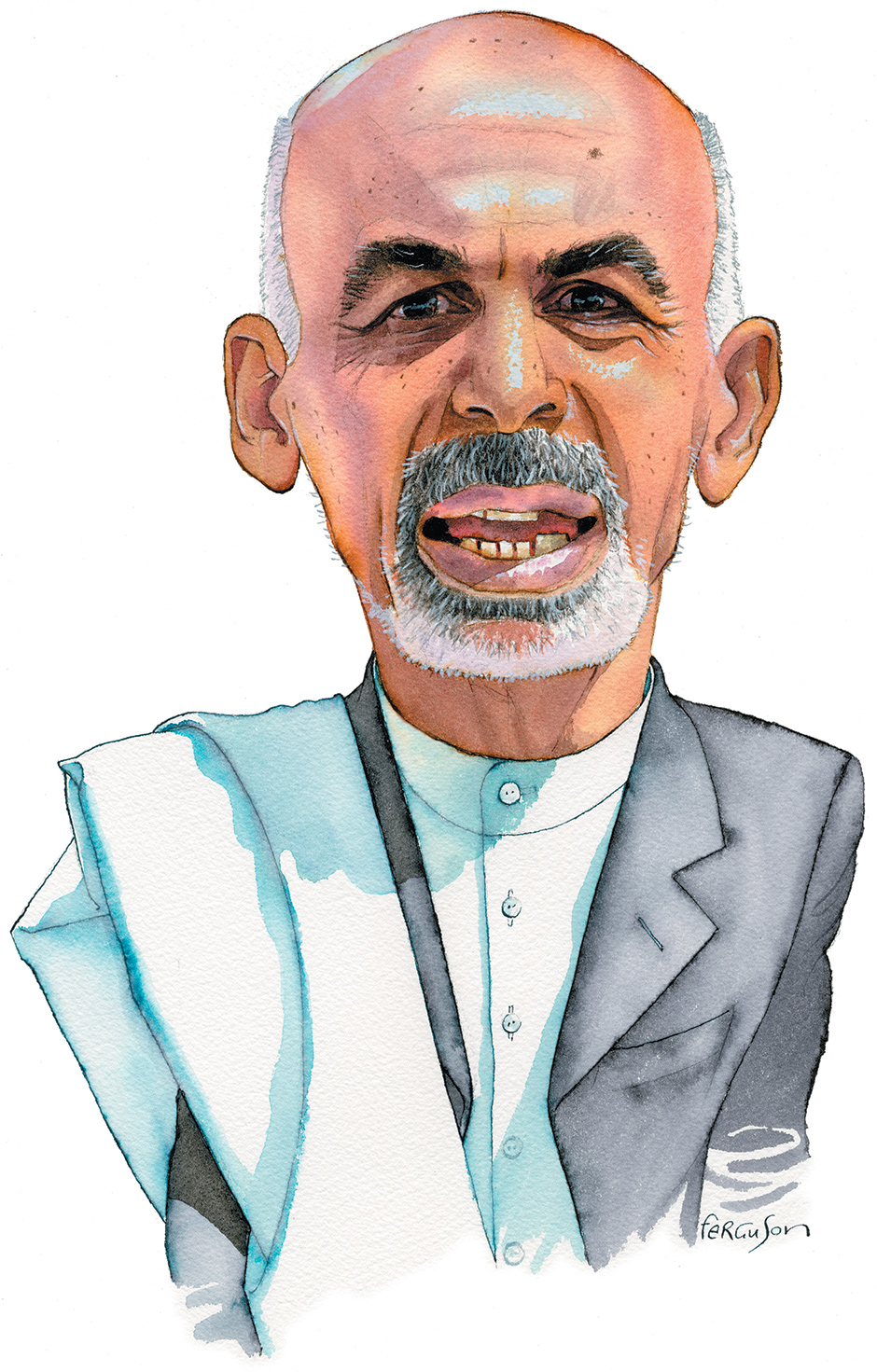

Ashraf Ghani, who has just become the president of Afghanistan, once drafted a document for Hamid Karzai that began:

There is a consensus in Afghan society: violence…must end. National reconciliation and respect for fundamental human rights will form the path to lasting peace and stability across the country. The people’s aspirations must be represented in an accountable, broad-based, gender-sensitive, multi-ethnic, representative government that delivers daily value.

That was twelve years ago. No one speaks like that now—not even the new president. The best case now is presented as political accommodation with the Taliban, the worst as civil war.

Western policymakers still argue, however, that something has been achieved: counterterrorist operations succeeded in destroying al-Qaeda in Afghanistan, there has been progress in health care and education, and even Afghan government has its strengths at the most local level. This is not much, given that the US-led coalition spent $1 trillion and deployed one million soldiers and civilians over thirteen years. But it is better than nothing; and it is tempting to think that everything has now been said: after all, such conclusions are now reflected in thousands of studies by aid agencies, multilateral organizations, foreign ministries, intelligence agencies, universities, and departments of defense.

But Anand Gopal’s No Good Men Among the Living shows that everything has not been said. His new and shocking indictment demonstrates that the failures of the intervention were worse than even the most cynical believed. Gopal, a Wall Street Journal and Christian Science Monitor reporter, investigates, for example, a US counterterrorist operation in January 2002. US Central Command in Tampa, Florida, had identified two sites as likely “al-Qaeda compounds.” It sent in a Special Forces team by helicopter; the commander, Master Sergeant Anthony Pryor, was attacked by an unknown assailant, broke his neck as they fought and then killed him with his pistol; he used his weapon to shoot further adversaries, seized prisoners, and flew out again, like a Hollywood hero.

As Gopal explains, however, the American team did not attack al-Qaeda or even the Taliban. They attacked the offices of two district governors, both of whom were opponents of the Taliban. They shot the guards, handcuffed one district governor in his bed and executed him, scooped up twenty-six prisoners, sent in AC-130 gunships to blow up most of what remained, and left a calling card behind in the wreckage saying “Have a nice day. From Damage, Inc.” Weeks later, having tortured the prisoners, they released them with apologies. It turned out in this case, as in hundreds of others, that an Afghan “ally” had falsely informed the US that his rivals were Taliban in order to have them eliminated. In Gopal’s words:

The toll…: twenty-one pro-American leaders and their employees dead, twenty-six taken prisoner, and a few who could not be accounted for. Not one member of the Taliban or al-Qaeda was among the victims. Instead, in a single thirty-minute stretch the United States had managed to eradicate both of Khas Uruzgan’s potential governments, the core of any future anti-Taliban leadership—stalwarts who had outlasted the Russian invasion, the civil war, and the Taliban years but would not survive their own allies.

Gopal then finds the interview that the US Special Forces commander gave a year and a half later in which he celebrated the derring-do, and recorded that seven of his team were awarded bronze stars, and that he himself received a silver star for gallantry.

Gopal’s investigations into development are no more encouraging. I—like thousands of Western politicians—have often repeated the mantra that there are four million more children, and 1.5 million more girls, in school than there were under the Taliban. Gopal, however, quotes an Afghan report that in 2012, “of the 4,000 teachers currently on the payroll in Ghor, perhaps 3,200 have no qualifications—some cannot read and write…80 percent of the 740 schools in the province are not operating at all.” And Ghor is one of the least “Taliban-threatened” provinces of Afghanistan.

Or consider Gopal’s description of the fate of several principal Afghan politicians in the book:

Dr. Hafizullah, Zurmat’s first governor, had ended up in Guantanamo because he’d crossed Police Chief Mujahed. Mujahed wound up in Guantanamo because he crossed the Americans. Security chief Naim found himself in Guantanamo because of an old rivalry with Mullah Qassim. Qassim eluded capture, but an unfortunate soul with the same name ended up in Guantanamo in his place. And a subsequent feud left Samoud Khan, another pro-American commander, in Bagram prison, while the boy his men had sexually abused was shipped to Guantanamo….

Abdullah Khan found himself in Guantanamo charged with being Khairullah Khairkhwa, the former Taliban minister of the interior, which might have been more plausible—if Khairkhwa had not also been in Guantanamo at the time….

Nine Guantanamo inmates claimed the most striking proof of all that they were not Taliban or al-Qaeda: they had passed directly from a Taliban jail to American custody after 2001.

Why didn’t I—didn’t most of us—know these details? The answer is, in part, that such investigative journalism is very rare in Afghanistan. Gopal’s work owes a lot to other researchers. He is building on the work of Sarah Chayes and Alex Strick van Linschoten (both of whom immersed themselves in the Pushtu south), of exceptional journalists such as Carlotta Gall and David Rohde of The New York Times, of officials with years in the country such as Eckart Schiewek, Robert Kluijver, and Michael Semple, and of Afghan journalists such as Mohammed Hassan Hakimi.

Advertisement

Afghanistan, however, is not an easy place for in-depth reporting. Foreign civilians have been targets, even in the safer areas, since 2001, when the first Spanish journalists were executed near Jalalabad. Gopal—an American civilian—pursued his stories into the most active centers of the insurgency—the inner districts of Ghazni, Uruzgan, Helmand, Kandahar, and the Korengal valley in the northeast—places where thousands of international troops have been killed. He learned Dari and—more difficult—Pushtu. He won the trust of insurgent leaders.

But his real genius lies in binding all these sources together and combining them with thousands of hours of interviews. He tracks down the Taliban commander who attacked the provincial capital of Uruzgan in 2001, and then he interviews the US Special Forces commander who was defending it. He shows us the US commander ordering the air strike, and the Taliban commander seeing the same bomb destroy the jeep in front of him. He researches individuals by interviewing them, their neighbors, and their enemies, and then traces the very same people through Human Rights Watch reports, State Department documents (via WikiLeaks), US Army press statements, and Guantánamo interrogations and arrest reports.

All this allows him to bring life to figures who have hitherto been caricatures. Human Rights Watch reports have long emphasized the crimes of warlords such as Sher Muhammed Akhunzada, Jan Muhammed, or Abdul Rashid Dostum. But policymakers have still been tempted to perceive them also as charismatic rogues and inescapable parts of the Afghan establishment. Their links to organized crime, the CIA, Pakistani intelligence officers, and the international narcotics trade can seem simply elements of their machismo. Their scams—running construction companies, private security agencies, developing property, importing and exporting oil and opium poppy, and providing logistical support for the foreigners currently on temporary duty in Afghanistan—can seem simply colorful.

Ambassadors, for example, often joke about Dostum’s heavy drinking and his extravagance (he is rumored to have paid $100,000 for a fighting dog). A Washington Post journalist records Dostum thundering, when posing for his US visa photo: “My friend, even if you take a picture of my ass, the US will know this is Dostum.” All the American generals, Pakistani intelligence chiefs, heads of European NGOs, ambassadors, ministers, and foreign correspondents who have met Dostum over thirty years compete to tell such anecdotes. He cooked hundreds of Taliban prisoners to death in shipping containers. But he has just become vice-president.

Gopal’s deep investigation, however, brings out, in detail, the real horror inflicted by such men. His long interviews with warlords, his sympathetic accounts of their youth and sufferings, make their crimes only more convincing and more shocking. Thus he interviews Jan Muhammed at length, tracing his rise from school janitor to major resistance commander in the fight against the Soviet Union. He describes his being imprisoned, the tortures he suffered, and his being marched out to face a Taliban firing squad. He describes how Jan Muhammed saved President Karzai from an ambush in the 1990s and then became his friend and adviser.

All this, however, is the introduction to Jan Muhammed ordering death squads to shoot unarmed grandfathers in front of their families, to electrocute and maim, and to steal people’s last possessions, in pursuit of an ever more psychopathic crusade to eliminate anyone associated with the Taliban or indeed with a rival tribe. No one reading Gopal would be tempted to joke about these men again, or present them simply as “traditional power-brokers” and “necessary evils.”

The same careful research allows Gopal to reveal not only the conservatism of Afghan rural life, but also its startlingly modern elements. His description of the rural south, for example, where a woman is a piece of property—the “government would no more intervene in [killing your wife] than it would if you had in some private rage killed your own oxen or damaged your own house”—may seem familiar. But he also uncovers unexpected mobility and lurches in status behind the blank mud walls of the compounds. One long interview (it forms the basis for almost a quarter of the book and must have taken many days to complete) reveals that an impoverished woman, locked with her mother-in-law in Khas Uruzgan, was educated at Kabul University, and once lived unveiled in a prestigious Soviet-designed apartment block in the capital city.

Advertisement

Her husband—who beat her for leaving the house—was a progressive leftist and a proto-feminist who once encouraged her to work. When her husband was murdered and her ten-year-old son badly wounded in a gunfight, she was reduced almost to starvation in the southern city of Kandahar, and then suddenly, through a family patron, found herself elected the first female member of Parliament from Uruzgan.

Gopal’s astonishing stories are not, however, a complete portrait of Afghanistan. He is so immersed in the mayhem and abuse that he seems genuinely to believe—as the title of the book suggests—that in Afghanistan there are “no good men among the living.” The more difficult truth is that it is hard to describe living among Afghans without falling back on words like dignity, honor, courage, strength, and generosity. Many of the Afghans I have worked with epitomize these virtues so clearly, and even quixotically, that they can seem almost a rebuke to our age.

Gopal must have experienced this—with the Afghan friends, for example, who accompanied him on motorbikes into the heart of the insurgency. Walking across Afghanistan, and working in a very traditional community in the capital, I came to know dozens of authority figures who were men of striking charisma, energy, and sense of responsibility, clearly knowledgeable and competent in their immediate society. Gopal must have known many too. And he must have noted how even the villains of his book had been prepared to risk their lives, again and again, whether for religion, patriotism, or simply pride—and how calmly they lived, knowing that they would eventually be captured or killed. (A high proportion of the people he interviewed have since been murdered or imprisoned.) But he does not explore these virtues. And above all, he doesn’t capture their sense of humor. Afghans smile and laugh more than almost any people I know.

2.

Ashraf Ghani is now—after four months of wrangling over electoral fraud—the new president of Afghanistan. His book Fixing Failed States (coauthored with Clare Lockhart) argues that Afghanistan can be fixed through creating ten functions of the state, including the “rule of law,” good governance, and a state “monopoly on the legitimate means of violence.” Along the way he proposes eliminating corruption, disarming and demobilizing militias, and creating a reliable justice system and a prosperous economy. Having spent three decades as a professor, a World Bank official, and an Afghan minister developing this intricate theory, he is now putting it into practice.

The leaders of the US intervention in Afghanistan once had very similar objectives—often directly influenced by Ashraf Ghani, who has been the most tenacious and articulate advocate of this vision of “state-building” since September 11. Similar concepts appear in General David Petraeus’s US Army counterinsurgency manual and in presidential envoy James Dobbins’s The Beginner’s Guide to Nation-Building. Much of the $1 trillion spent by the US and its allies in Afghanistan, and the more than a million people, deployed over a dozen years, have been justified in such terms. President Obama may in fact have been unconsciously quoting Ghani when he explained that Afghanistan’s problems with narcotics and women’s rights, and even the instability of neighboring states, could be solved through the creation of “a credible, effective, legitimate state.”

State-building, however, is not confined to Afghanistan. Ghani has promoted exactly the same recipe from Nepal to Ethiopia as the copresident of the Institute for State Effectiveness. And it seems to be immensely appealing. For the World Bank in 2013, state-building was the solution to piracy in Somalia. For French President François Hollande in 2013, “restoring the state, improving governance” were the first steps in tackling trafficking and violence in Mali. UN Secretary-General Ban Ki Moon distilled the theory of Afghanistan’s civilian surge in his 2014 bon mot “Missiles may kill terrorists. But good governance kills terrorism.”

Gopal’s book, however, should at least make us question this fashion of state-building under fire. What has actually been the result of Afghanistan’s $1 trillion attempt to create “security,” “economic development,” and “governance”? What did creating security mean in Khas Uruzgan where, Gopal explains, all the traditional leaders had been killed and where the only counterbalance to the Taliban was an illegal militia? How could the “police” be trusted to establish a “monopoly on the legitimate means of violence” if—as Gopal records—“in Wardak’s multiparty, multiethnic district of Jalrez, for instance, all sixty-five members of the police force hailed from a single pro-Sayyaf village”? (Sayyaf is a Pashtun warlord.)

What future was there for the Afghan economy when, as Gopal shows, it relied on servicing, supporting, and seeking rent from two hundred thousand foreign soldiers and civilian contractors, and where Afghan “businessmen” were often simply warlords profiting from security, supply, and construction contracts generated by US military bases? How would any of this be sustainable after the troops withdrew?

Aid agencies put billions directly into the budget of the Afghan government, on the grounds that this strengthened the “accountability” and “legitimacy” of the Afghan state. But much of the Afghan bureaucracy, including the ministries most popular with donors (education, for example), were paying money to employees who did not even pretend to work; and the regulations, tax inspections, and administrative orders were generally simply opportunities for nepotism, revenge, or bribes. Again and again Gopal reminds us that the state, which the West was supposed to be developing, was far weaker than anyone acknowledged—and often simply didn’t exist.

In truth, international statements about establishing “the rule of law, governance, and security” became simply ways of saying that Afghanistan was unjust, corrupt, and violent. “Transparent, predictable, and accountable financial practices” were not a solution to corruption; they were simply a description of what was lacking. But policymakers never realized how far from the mark they were. This is partly because most of them were unaware of even a fraction of the reality described in Gopal’s book. But it was partly also that they couldn’t absorb the truth, and didn’t want to. The jargon of state-building, “capacity-building,” “civil society,” and “sustainable livelihoods” seemed conveniently ethical, practical, and irrefutable. And because of fears about lost lives, and fears about future terrorist attacks, they had no interest in detailed descriptions of failure: something had to be done, and failure was simply “not an option.”

3.

Recently, as chair of the UK Parliament Defence Committee, I voted on air strikes in Iraq, and saw state-building’s enduring appeal. The prime minister opened the debate by saying that his strategy depended on “the creation of a new and genuinely inclusive government in Iraq [and] a new representative and accountable government in Damascus.” An ex–cabinet minister argued that the solution to ISIS was to “focus on local governance and accountability.” A shadow minister replied that “there needs to be a wider, encompassing political framework, with a plan for humanitarian aid and reconstruction, which will ultimately lead us to create a stronger and more accountable Iraqi government.”

This is the intellectual frame within which Britain and many others have now decided to mount air strikes against ISIS, supplemented by counterterrorist operations to kill and capture ISIS commanders. The new coalition will pay, arm, and reinforce Iraqis and Syrians to attack our enemies. And we will replace ISIS with a credible, legitimate, inclusive state in Iraq and Syria. Before perhaps turning to Yemen, or Somalia, or returning to Libya.

But Gopal shows us clearly how easy all this is to say, and almost impossible to do. Why should we be any better at targeting ISIS than we were at targeting the Taliban and al-Qaeda? We are now funding Syrian and Iraqi militia commanders and tribal leaders. In Afghanistan such commanders made themselves wealthy off international contracts, misrepresented their rivals as terrorists, and used their connections with us to terrorize and alienate the local population. How different will our new allies be from Afghan warlords such as Jan Muhammed or Abdul Rashid Dostum? We already tried counterinsurgency and state-building in the same area of Iraq in response to a very similar group—al-Qaeda in Iraq—in 2008. We invested $100 billion a year, deployed 130,000 international troops, and funded hundreds of thousands of Sunni Arab militiamen. And the problem has returned, six years later, larger and nastier.

This is not a reason to reject intervention entirely—Bosnia, for example, was a success. But we should not pretend that a global model for “nation building under fire” is the answer. “Governance,” “the rule of law,” and “security” have different meanings in different cultures and are shaped by very local structures of power. Insurgencies vary with what remote and often little known communities think of themselves, their leaders, their religion, their past, and the outside world. Building a state or tackling an insurgency therefore requires deep knowledge of the history and character of an individual country. And such activity demands that Western governments acknowledge how little they know and can do in most of these places and cultures. But the startling differences within the countries in which we intervene are only exceeded by the startling uniformity, overconfidence, and rigidity of the Western response.

The question we need to ask today is not “How do you create good governance, economic development, and security?” Instead, we should be asking “Who makes up ISIS, and why are they getting tacit support from the Sunni population?” Are either the Iraqi state or army a credible alternative? What view have rural Sunnis developed of the West, of the “surge,” or extremism? Could the Kurds hold a new front line if ISIS continued to occupy Mosul? How would you convince the Kurdish leadership to allow the peshmerga to become a professional force, when it remains the essential channel of patronage and power for the major political parties?

How do you bring Turkey to actively support the fight against ISIS? How do you convince people in the Gulf to cease financing it? How do you stop Iraq and Syria being simply pawns in a much bigger fight between Iran and its Sunni opponents? What support can you provide for the people living under ISIS, to allow them to slowly escape this circle of horror? And how do our—the interveners’—institutions, conceptual models, weapons, and dollars undermine and distort our relationships, corrode our programs, and defeat our own stated objectives?

These are the kinds of questions—rooted in politics, culture, and lived experience—that we should have been posing in Afghanistan, instead of refining universal models of “state-building.” Such are the questions that only studies such as Gopal’s can answer.

This Issue

November 6, 2014

‘Broken Windows’ and the New York Police

The Genius in Exile