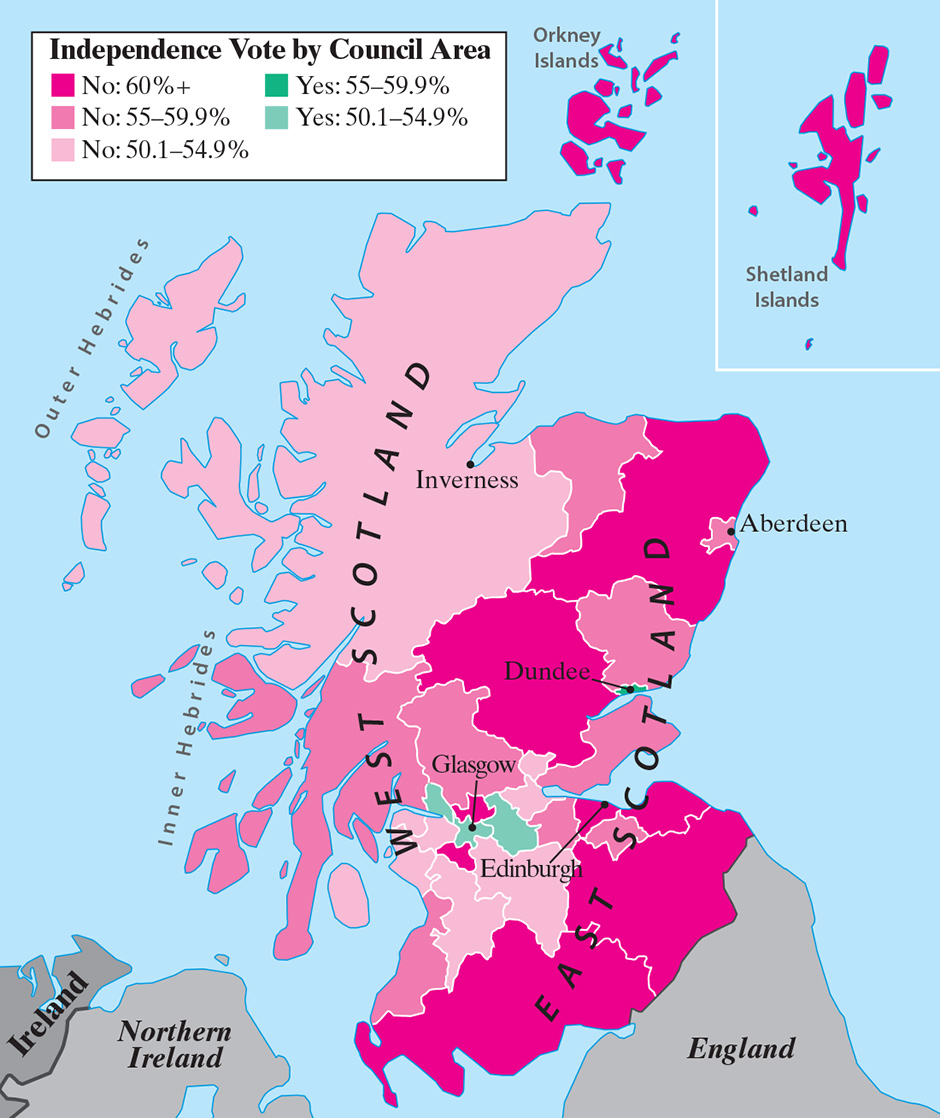

Around lunchtime on Friday, September 19, an advocate of a united Britain could have looked at a political map of Scotland and, like the Queen (if David Cameron’s account to Michael Bloomberg can be believed), purred with pleasure that a disaster had been averted and all would now be well. Television showed Scotland’s familiar outline—ragged with islands and inlets to the west, smooth and solid to the east—and almost all of it colored magenta by the BBC to indicate that the electorate had rejected independence by voting No in the previous day’s referendum.

The shade deepened according to the strength of the No in each of the twenty-eight (out of thirty-two) local authorities that had voted that way. The nation’s perimeter looked almost purple: the border country with England and the northern archipelagoes of Orkney and Shetland had rejected independence by a two-thirds majority. Elsewhere, in the cities of Edinburgh and Aberdeen and all the way down both coasts, the No figure was around 60 percent. The lowest margin, represented in the palest pink, came in Inverclyde, which chiefly comprises the industrially derelict town of Greenock, where only 50.08 percent of voters wanted to persist with the union.

The Yes-voting areas were represented in light blue on the BBC’s map, but they weren’t immediately easy to make out: two small blobs for the cities of Dundee and Glasgow with two larger blobs for East Dunbartonshire and North Lanark. Dundee had the darkest shade: 57.35 percent had voted Yes there, while the other three registered between 51 and 55 percent.

But what were these four small blue splashes of Yes compared to the great magenta lands of No around them, where it sometimes seemed as if even the sheep had turned up to be counted? A record turnout of 84.6 percent—higher than in any UK general election since the introduction of universal male suffrage in 1918—had split 44.7 percent to 55.3 percent against independence. In the last days of the campaign, polling showed the two sides much closer.

This was an unexpectedly decisive result and soon after midday Alex Salmond announced his intention to resign as Scotland’s first minister and the Scottish National Party’s leader. In two years of campaigning, Salmond had always spoken of the referendum as an opportunity for Scottish independence that wouldn’t be repeated for a generation—this would be the moment that had to be seized, it was more or less now or never. (The No campaign insisted for similar reasons—to maximize turnout—that the decision would be final, that there could be no going back.) Now, however, Salmond struck a different note. Scotland would need “to hold Westminster’s feet to the fire” over its recent promises to devolve meaningful power to Scotland’s government; the best guardians of this progress, he said, weren’t politicians “but the energized activism of tens of thousands of people who I predict will refuse meekly to go back into the political shadows.” The new situation was “redolent with possibility.” Scotland could still emerge as “the real winner.”

Losers’ speeches tend always to make the best of a bad job, but the extraordinary political developments over the next two weeks fully justified Salmond’s optimism. Between September 19 and October 1 almost 50,000 people joined the Scottish National Party (SNP), tripling its membership, with the Scottish Greens, the SNP’s main allies in the Yes camp, also tripling its membership (to a more modest total of 6,000) over the same period. By the end of September the SNP’s membership of 75,000 and rising had made it the third-largest political party in the United Kingdom after Labour and the Conservatives, displacing the Liberal Democrats, a famously “grassroots” organization whose alliance with the Conservatives in the coalition government has alienated many of its traditional supporters. The figure means that nearly 2 percent of the Scottish electorate are SNP members—a higher density of the politically committed among the general population than can be achieved in England by combining the membership of all its parties, to give the SNP a greater political reach than any rival could dream of.

So far as one can tell, none of this was planned; it has been a spontaneous reaction by Yes voters to defeat. This is the first reason to think that the referendum is very far from a conclusive settlement of the Scottish question, and indeed may amount to no more than a holding operation. For the Scottish Labour Party, which is the source of many of the SNP’s new recruits, the forecast looks particularly bleak.

Nobody who grew up in postwar Scotland can doubt that the rise of the independence movement has been the most important political development of their lifetime, as well as, for some of us, the most surprising. As a child in the early 1950s, I heard my parents talk of nationalism as the foolish preoccupation of a tiny band of eccentrics who (for example) defaced or blew up new Royal Mail postboxes because they carried the recently crowned Queen’s cipher as EIIR, Elizabeth II. Since Elizabeth I’s reign never extended to Scotland, it should have read EIR or simply ER. The first nationalist I knowingly encountered was a boy in my class at school who wore a kilt of Black Watch tartan and a saltire lapel badge. Sometimes we would argue over the prospects for a separate Scottish navy or a railway system powered entirely by hydroelectricity from the lochs and glens.

Advertisement

In a school of a thousand pupils, he was, I think, the only one who could imagine Scotland as a separate country and one of the few to wear the kilt, which in those days was a dress mainly confined to Scottish regiments and pipe bands, and frequently mocked as a piece of upper- and middle-class whimsy by that part of the working-class population that took pride in the egalitarian appeal of Robert Burns and the internationalism of the socialist tradition.

Not that Scotland could then be considered inherently more social democrat or communitarian a country than its big neighbor to the south, which is what it now likes to believe. People in all social classes revered the Queen, admired Churchill, and thought fondly of the shrinking Empire. In the general election of 1955, the Unionist-Tory share of the voted reached 50.1 percent, with another 46.7 percent voting Labour and an imperceptible 0.5 percent for the SNP.

Nationalism was then seen as an almost purely cultural phenomenon: an essentially backward-looking movement most prominently supported by poets such as Hugh MacDiarmid who wanted to de-Anglicize Scottish literature, or by Jacobite hobbyists and others who imagined that the 1707 Treaty of Union had been an act of betrayal rather than the path to a productive era of enterprise and invention, the proud evidence of which still lingered in such artifacts as the Forth railway bridge and the great Cunard liners.

In fact, this idea of nationalism as mere sentimentality was unfair; better governance through greater autonomy had been promised by the radical wing of Liberal governments as early as the 1880s, culminating in “Home Rule” legislation that had its progress through Parliament cut short by the outbreak of World War I. That and similar Home Rule commitments by the early Labour Party had been relegated to obscure history in the postwar years, when the word “nationalism” had become the victim of a “vulgar syllogism,” in the words of the writer Neal Ascherson: “Nationalism equals racism equals fascism equals war.”

The SNP, founded in 1934, for many years stood on this difficult ground that had Brigadoon on the one side and the Holocaust on the other, but by the late 1960s it had become a useful vehicle for the protest vote of an electorate that had begun to be disenchanted by the two big British parties. The discovery of oil under the North Sea demolished the argument that the Scottish economy would shrivel without support from London; in 1971 the SNP began to campaign with a new slogan—“It’s Scotland’s Oil”—that, as the historian Tom Devine writes,

brilliantly exploited the contrast between…the fabulous wealth found off Scotland’s coasts and…the fact that by then the Scots had the worst unemployment rate in western Europe and were yoked to a British state that stumbled from crisis to crisis.1

The reward came in the general election of October 1974, when the SNP took almost a third of the Scottish vote and won eleven Westminster constituencies, most of them rural and previously held by Conservatives. The party’s economic ideology was then uncertain—their Labour opponents dubbed them “Tartan Tories”—but over the next decades they moved steadily toward the center-left, mainly in response to the neoliberalism of Margaret Thatcher’s administration, which many in Scotland blamed for the final collapse of the country’s heavy industry. Thatcher’s abrasive personality and her imposition of a regressive local taxation—tried in Scotland before it was rolled out in the rest of the UK—added to her loathsome reputation (a character in a Glasgow pantomime bore the name “the Wicked Witch of the South”).

The Tories in Scotland never recovered. Today they have only one Westminster MP out of Scotland’s total of fifty-nine. A measure of their self-knowledge came during the referendum in a speech by David Cameron, when the prime minister said it would be heartbreaking if people voted to break up the union just to give “the effing Tories [i.e., people like himself]…a kick.”

Advertisement

By contrast, Labour’s position at the turn of the century looked secure. One of the first acts of Tony Blair’s government was to hold the referendum that established a Scottish parliament in 1999; the devolution of powers from Westminster gave it control of all matters apart from foreign policy, defense, social security, the macro-economy, and broadcasting. Elected by a system of proportional representation that was designed to deny any party (but particularly the SNP) a clear majority, the Scottish parliament was thought to have killed off any demand for secession.

The Labour–Liberal coalitions that ran the first two administrations tended to confirm that view, but then in 2007 the SNP formed a minority government under its gifted leader Alex Salmond that proved competent and popular. Three years later David Cameron’s coalition replaced Labour as the UK government; London and Edinburgh were now more clearly at odds and the SNP could again make the claim, which had been potent in Thatcher’s day, that Scotland was being ruled by a party that it hadn’t elected and that was inimical to its interests. In the Scottish parliamentary elections of 2011, the SNP won sixty-nine out of 129 seats and began negotiations with London to implement the referendum that it had promised in its manifesto.

For the first time, nationalism had made serious inroads into Labour’s heartland in the old mining and manufacturing districts of the lowland west, where Blair’s New Labour government (and particularly its role in the invasion of Iraq) had alienated long-standing supporters and where the party machine was complacent and sclerotic. For decades Labour had depended on what was known as “the Catholic vote,” but the Church’s hierarchy no longer tried to persuade its Ireland-descended faithful in any particular political direction (and would not have been heeded if it had).

This year, the SNP knew that it needed to repeat this success in west Scotland—in Glasgow and its formerly industrial hinterland—if the referendum was to be won. Together with newly formed socialist groups in the Yes campaign, it stressed the misery that neoliberalism and the UK government’s austerity policy were bringing to many areas that were already poor and run-down, particularly the towns and settlements around Glasgow that until forty and fifty years ago rolled steel, made ships, and dug coal. Yes campaigners reproached the London government for benefit cuts, food banks (the modern equivalent of soup kitchens), and alleged threats to the funding of the National Health Service, and envisaged a happier future in which a more generous welfare system would be sustained by the tax revenues from North Sea oil.

The social divide in Scotland is west–east rather than England’s better-known north–south. One result of the SNP’s referendum strategy, with its focus on poverty, was an apparent rearrangement of its priorities. Other than the lowland west and the old jute city of Dundee, many parts of Scotland are prospering. To the poor, who were concentrated mainly in the west, independence offered more promise than risk; it was the richer east that worried more about the new currency arrangements and the possible flight of jobs from Edinburgh’s financial sector, that listened when economists such as Paul Krugman in The New York Times said it should “be afraid, be very afraid” of using sterling as a shared currency, or when oil executives doubted the SNP’s high estimate of exploitable reserves.

The Yes vote, therefore, did best where people were poorest and had the least to lose, which meant that the SNP won some of the west and lost almost all the east: for a party that built its original success on the back of the oil boom and that was once at its liveliest among the lawyers and tradesmen of country towns, this was an irony.

Krugman, a Nobel laureate, was only one among many of the internationally famous who felt Scottish independence was a risk not worth taking: the list included Barack Obama, Bill Clinton, J.K. Rowling, the European Commission President José Manuel Barroso, and the Pope (whose comments in June seemed to provide support to the No side). Every British newspaper, apart from Glasgow’s Sunday Herald, was also against it or, in one or two cases, ostentatiously neutral. For a time it seemed as though the Scottish edition of Rupert Murdoch’s Sun would endorse a Yes vote, but in the end Murdoch drew back, unsure how meddlesome with the free market an independent Scotland would be. The governor of the Bank of England joined Krugman in thinking that Alex Salmond’s plan to share the pound was unwise. David Bowie’s plea—“Scotland, stay with us”—was echoed by every kind of pop star, actor, and comedian. Any positive effect for the No side was hard to detect.

The Yes campaign continued to be the more energetic, the more optimistic, the better organized, the more adept user of social media. It was seen everywhere. Come the result, this visibility proved to have been deceptive, but as the polls began to narrow in August it became hard to resist the notion that Yes might win. In my own small town, men and women in their sixties told me that they would vote for the first time in their lives, and it was strange to think that these people who I knew, who had never expressed a political opinion or voted in the kind of lesser elections that might decide the composition of a local council or a new bus timetable—that their vote might create a new nation. “A festival of democracy” was how Salmond described it, while the novelist Irvine Welsh, writing after the result (and ignoring it), thought that the Scots had

shown the western world that the corporate-led, neo-liberal model for the development of this planet …has a limited appeal…. Forget Bannockburn or the Scottish Enlightenment, the Scots have just reinvented and re-established the idea of true democracy.

More demonstrably, what they had done was to give the rest of Britain a scare. When a poll on September 7 put Yes in the lead for the first time—by 51 to 49 percent once the 7 percent of Don’t Knows was removed—a wave of selling on the foreign exchanges sent the pound down against the dollar by nearly one and a half cents.2 The pound recovered; the political consequences were more serious and longer lasting. The English leaders of three big unionist parties—Cameron plus the Liberal Democrats’ Nick Clegg and Labour’s Ed Miliband—flew north three days later, having taken the decision (“unprecedented” according to reports) to cancel Prime Minister’s Questions, which is one of the House of Commons’ most important weekly rituals.

Their presence in Scotland was unexpected; Westminster is now such an unpopular institution, even among unionists, that its leaders had stayed away on the grounds of their negative influence (heightened because all three men are dark-suited career politicians in their middle forties, all born in or near London, and all educated at Oxbridge). What emerged from their panic was a joint strategy that promised increased powers to the Scottish government if the Scottish people voted No. This wasn’t a new idea—all three parties had their earlier versions of it—but now it was solemnized and publicized as “the Vow” that guaranteed “extensive new powers” to be delivered by an urgent timetable that had already been announced by Gordon Brown, the former Labour prime minister who strongly supported a No vote and whose interventions in the debate now became prominent.3 What the Vow put back into play was a solution to Scottish aspiration through maximum devolution of power to Scotland: every power possible would be devolved to Scottish government, short of those—defense, foreign policy, the bank rate—that would make it a separate state.

In 2012 Cameron had ruled out this option—called “devo max”—as the third question on the ballot paper, and now rather slyly it had returned as the reward for voting No. Few details were attached, beyond the commitment to leave NHS funding entirely in the hands of the Scottish government and to retain the so-called Barnett formula, by which the Treasury fixes levels of public spending across the four nations of the United Kingdom, and which per capita currently gives Scots about a tenth more than the English.

Nor is it clear how much the pledge affected the outcome. A post-referendum poll by Lord Ashcroft, the pollster and Tory party backer, had some interesting findings. Voters aged more than 55 were the only age group with a No majority—by forty-six points in the case of those more than 65; the 25–34 group had the largest Yes vote—a sixteen-point lead. One in seven SNP supporters voted No but four in ten Labour and Lib Dem supporters voted Yes. Women were more inclined to vote No; two thirds of the people who made late decisions voted Yes; the well-off favored No by 60/40.

Why the voters had reached such decisions was harder to disentangle. In the weeks since, the idea has become commonplace that everybody, both Yes and No, wanted some degree of change in governance. But many more in Lord Ashcroft’s two-thousand-person sample said they voted No because independence posed economic risks, rather than because they believed their vote would deliver extra powers for the Scottish parliament inside the “security” of the UK.

The Vow’s larger and more tumultuous legacy promises—or threatens—to be a dramatic upheaval in the way the UK is governed. If Scotland is to have what Gordon Brown calls “Home Rule,” where does that leave Wales and Northern Ireland? Most important, where does it leave England? Arguments that for years were confined to fringe meetings at party conferences, or scatterings of eccentrics gathered in hired rooms, are becoming center stage.

Should there be a separate English parliament? Could the United Kingdom be a properly federal state, with a senate or national assembly drawn from its four nations replacing the House of Lords? For how much longer can the Commons leave the famous West Lothian Question—whether MPs from Northern Ireland, Scotland, and Wales can vote on questions affecting only England4—unaddressed and allow Scottish MPs to continue to vote on legislation that applies only to England? Cameron promised “English votes for English laws” at his party’s annual conference in September, anxious to appease the growing force of English nationalism that is currently turning the UK Independence Party (UKIP) into a dangerous rival. But the Labour Party is much less keen; without the votes of its Scottish MPs (forty-one out of 256 in the present Parliament) it might struggle to find a majority.

Establishment panic at one opinion poll is an odd way to have arrived at this sudden new prospect. Meanwhile in Scotland, many are starting to believe that there are other roads to independence than once-in-a-generation referendums. How the SNP candidates do in next year’s UK elections will be the telling fact for the future.

-

1

Tom M. Devine, The Scottish Nation: A History, 1700–2000 (Viking, 1999). ↩

-

2

ICM was the only other poll to record a Yes lead during the two-year campaign—by eight points on September 12. Even when undecided voters were excluded, few polls put the Yes vote above 45 percent until the last weeks. ↩

-

3

His impassioned speech to Labour activists in Glasgow on September 17 was the highlight of the No campaign and widely watched online. ↩

-

4

Named after the former MP for that constituency, Tam Dalyell, who in early debates about devolution pointed out that a separate Scottish parliament would deprive English MPs of a similar say over Scottish laws. ↩