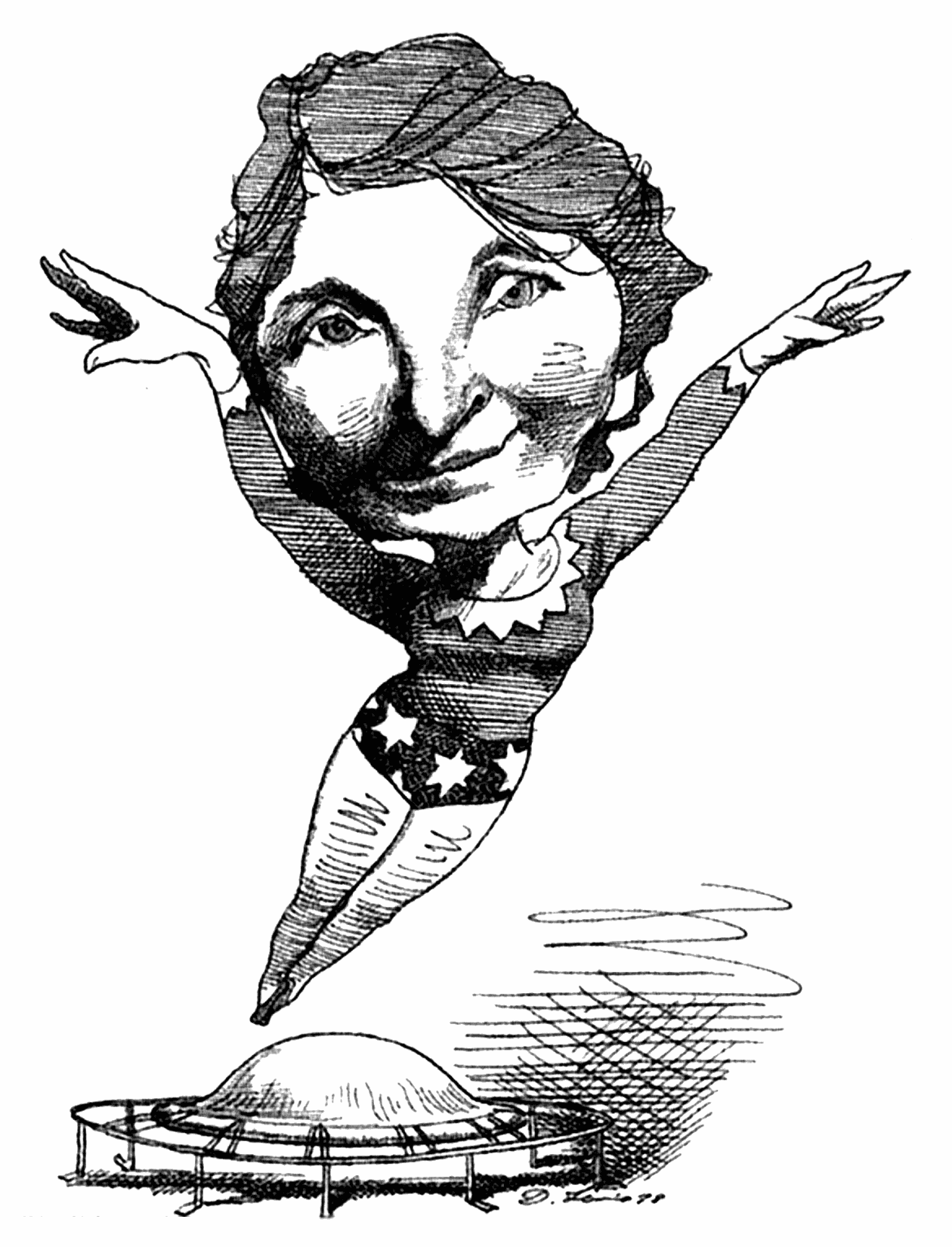

In 1978, David Levine drew the birth control pioneer Margaret Sanger wearing a leotard with stars below the waist, bouncing confidently off what looked at first like a trampoline. On second glance it was a springy contraceptive diaphragm. Of course: Sanger as Wonder Woman. (See illustration below.)

The choice of imagery was obvious. Many decades earlier, Sanger had argued that women should be taught about sex, its pleasures and consequences, and given the information and medical support they needed to determine their destinies as mothers (or as not-mothers, should they so choose). In cofounding America’s first birth control clinic in Brooklyn in 1916, Sanger launched a movement that would eventually complete the job of making contraception and reproductive medicine available in the United States and much of the world (even if rearguard legislative actions today keep the descendant of that early clinic, the now venerable Planned Parenthood, fighting to stay viable in America’s red states).

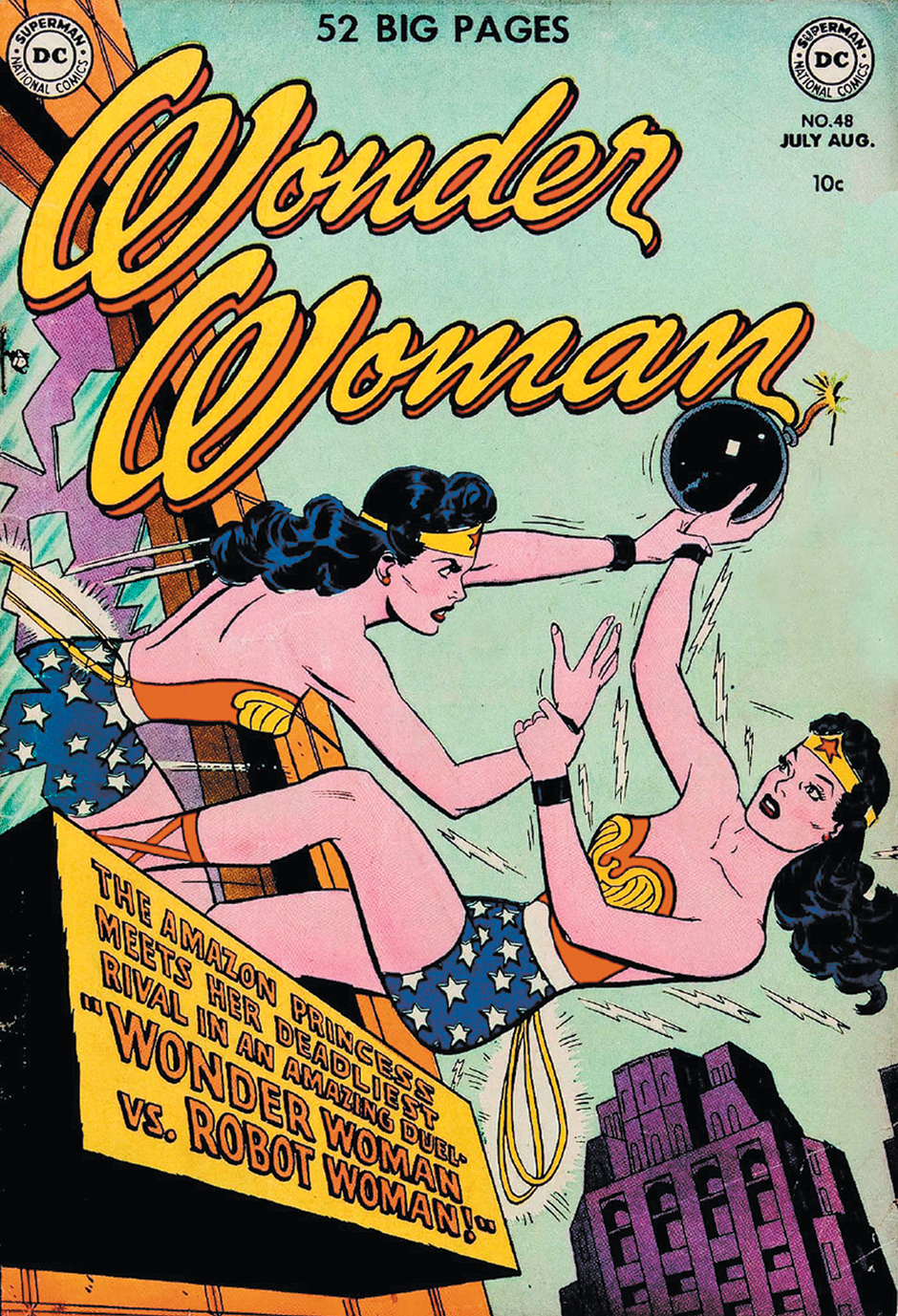

Wonder Woman was one of only a few symbols of womanhood who could be considered strong enough to win so big a battle. And she was enjoying a revival in the 1970s. In 1972, Gloria Steinem and the cofounders of Ms. magazine picked Wonder Woman to be the cover girl of its first issue. Ms. even helped publish a book, a culling of feminist-friendly story lines, that for decades was a much-used compilation of the comic’s early years. In the introduction, Steinem recalled the thrill she felt encountering at the age of eight this stunning, buff Amazon princess, flying by invisible airplane from her sheltered island to help America in World War II: “Looking back now at these Wonder Woman stories from the ’40s, I am amazed by the strength of their feminist message.”

It’s Jill Lepore’s contention in The Secret History of Wonder Woman that in looking back to the original Wonder Woman for a model, Steinem and her cofounders were on to more than a commercial hook. The superheroine, Lepore argues, has all along been a kind of “missing link” in American feminism—an imperfect but undeniable bridge between vastly distinct generations. Hiding in her kitschy story lines and scant costume were allusions to and visual tropes from old struggles for women’s freedom, and an occasional framing of battles like the right to a living wage and basic equality that have yet to be decisively won.

Wonder Woman stories showed women shackled in endless yards of ropes and chains—a constant theme in art from decades earlier demanding the right to vote. The traditional allegory of an island of Amazon princesses appears in feminist science fiction early in the twentieth century; the rhetoric of a nurturing, morally evolved strongwoman opposed to the war god Mars goes back even further. At the same time, the early comics often included a special insert, edited by a young female tennis champion and highlighting women heroes. Those chosen ranged from white suffragettes to Sojourner Truth to Elizabeth Barrett Browning, professional and sports pioneers, and a founder of the NAACP. It’s unlikely that any platform for American girls’ role models was as popular as this one until three decades later.

Wonder Woman was, in short, an explicitly feminist creation. Yet younger generations of feminists have lacked an awareness of the degree to which this is so, just as 1970s feminists were baffled when asked to identify pictures of the early suffragettes. So Wonder Woman is also the symbol of a culture-wide amnesia, part of the more general problem that American feminists can’t be inspired or taught the most useful lessons by their past until they gain a more cohesive sense of it.

On a literal level, too, Lepore has telling details to add to the feminist backstory of Wonder Woman. Officially, the comic (not a comic strip in a newspaper but a book following the serial adventures of a hero or in this case a heroine) was launched in 1941 by a man named William Moulton Marston. Marston, working under the name Charles Moulton, was without doubt the creator, but in practice he was assisted by his wife, Sadie Elizabeth Holloway Marston (sometimes called Sadie, sometimes Betty), and by a younger woman, Olive Byrne, who had lived with the married couple for years. After Marston died, in 1947, Sadie and Olive would live together for several more decades. The trio’s domestic arrangement has often been called “polyamorous,” a shorthand label that doesn’t quite capture its alternating vibes of sexual fluidity, personal and professional fusion, and the convenience of its work–life balance.

In any case, Olive became the main rearer of both women’s children by Marston. And Olive was none other than the niece of Margaret Sanger. To be precise, she was the daughter of Margaret Sanger’s younger sister—Ethel Higgins Byrne, who was a cofounder with Sanger of that first birth control clinic in 1916 and who, for a brief period after the sisters’ arrest for distributing contraception, achieved worldwide fame as America’s first hunger striker. More radical than Margaret, Ethel was soon to be marginalized from posterity, a result of her sister’s hardheaded sidelining of her from the kind of strategic movement Margaret intended to lead.

Advertisement

What are we to make of these interesting facts? William Moulton Marston was born in 1893 in what is now Saugus in northeast Massachusetts. His father was a wool merchant, while his mother grew up in what must have been a hothouse environment: a gigantic, turreted medieval castle built on a commanding hill north of Boston. Annie Moulton was one of five girls reared in the castle.

Lepore, scrupulous about not speculating where she lacks documentation, has disappointingly little to say about the scene of young Marston’s Sunday night family dinners at the castle. We learn that Marston was fussed over and multitalented, and by the eighth grade he had met the opinionated tomboy—Sadie, recently arrived in America with her family from Britain’s Isle of Man—who would be his sweetheart through college at Mount Holyoke, and soon enough his wife and close partner in various professional endeavors. When Marston was eighteen he contemplated suicide. Was he depressive? Was there some other precipitating event, or was it a weird instance of social contagion, some kind of passing adolescent fad for neo-Romantic melancholia? Not for the first time Marston comes across as mysteriously fascinating and a bit of a cipher.

At Harvard, he was a good student, outwardly a hail fellow well met but one who attended galvanizing speeches by the visiting British suffragette Emmeline Pankhurst, and was already a compulsive entrepreneur of his intellectual wares. When his family’s financial picture worsened, he entered and won a national screenplay-writing contest with a one-reeler about a college football player. He also got a law degree. But most of his achievements came in psychology, a field that was coming into its own, led by work being done at Harvard.

Here begins a side story in Marston’s life that enriches Lepore’s book, giving it a second layer of the kind of theme she excels at exploring, though it adds a few cul-de-sac wanderings. A Harvard historian as well as a New Yorker staff writer, Lepore specializes in excavating old flashpoints—forgotten or badly misremembered collisions between politics and cultural debates in America’s past. She lays out for our modern sensibility how some event or social problem was fought over by interest groups, reformers, opportunists, and “thought leaders” of the day. The result can look both familiar and disturbing, like our era’s arguments flipped in a funhouse mirror.

Marston studied with Hugo Münsterberg, a world-famous German psychologist recruited by William James, who had realized that Harvard’s department needed an experimental lab but didn’t feel like heading the effort himself. Münsterberg was a lightning rod of flashpoints, weighing in on topics ranging from how the new medium of movies molded viewers’ minds (he has been called film’s first theorist) to criminal evidence to the deeply unpopular German point of view on World War I.

One of Münsterberg’s best-known beliefs was in the inferiority of women, and Lepore draws the link between him and an early foe in Wonder Woman: the bitterly anti-woman scientist Dr. Psycho, a professor at Holliday College (Holliday College also being the home of Wonder Woman’s most dependable mortal friend, the fat and jolly student Etta Candy, who greets the superheroine’s telepathically brain-waved calls for backup with the catchphrase “Woo Woo!” and organizes an army of helpful coeds). Münsterberg was near the peak of controversy over his ideas when Marston came to work for him—he was soon to be ostracized for his pro-German views, and to die amid the stress. But while he worked for Münsterberg Marston invented a systolic blood pressure test that would become the basis of the lie detector.

The first half of Marston’s career was his attempt to make financial hay out of his invention. He misjudged its most promising future commercial use by police departments. Set up in the 1920s as chairman of the new department of psychology at American University, Marston helped to direct—in a closely watched national case, but in secret, even to the poor accused—his students’ defense of an African-American man charged with killing a distinguished African-American doctor. So focused was the defense on getting Marston’s lie-detector evidence admitted as a matter of principle that the team forgot to secure an alibi.

Advertisement

Worse, Marston’s error was horribly timed to coincide with his carelessness in a business proceeding. In the same month that the defense filed its appeal, newspapers reported that Marston, the presumptive scientific expert, had been arrested for fraud. The result was a brief, blunt ruling against the defense that Lepore astonishingly identifies as one of the most consequential decisions in the history of American criminal law—about standards that must be met when considering scientific expertise as evidence.

Marston appears to have been, if not a genius, clearly an original—and not unlike a comics character in his knack for getting into scrapes. During his decade in academia, he worked his way down the ladder from department chair to disposable adjunct. Still, Zelig-like in his ability to visit nearly every scene in the exploding field of psychology, he managed to be among early testers of American prison inmates and advised the army on how to deal with traumatized soldiers. He cooked up an early taste-test ad on behalf of Gillette razors.

He published an unusually tolerant academic book on the theory of human emotions, based on experiments some of which either Sadie or Olive, whom he met when she was his student at Tufts, had helped him conduct (Olive’s assistance included taking him to a “baby party” of blindfolded and bound freshman girl pledges, whom they interviewed about the pleasures of captivity and punishment). In Lepore’s description, Marston’s book argued that

much in emotional life that is generally regarded as abnormal (for example, a sexual appetite for dominance or submission) and is therefore commonly hidden and kept secret is not only normal but neuronal: it inheres within the very structure of the nervous system.

The book had one positive review—written under a pseudonym by Olive Byrne. But Marston’s theory was influential enough decades later to inform a test, still widely used, of how people behave in action. The theory also won for Marston a Hollywood stint as a moral-psychological adviser, until the Hays Code came along and rendered that job moot; one of his main ideas about the movies was that movie emotions must be believable, and for a love affair to be believable the woman must direct its course. The man’s job, beneath the bluffing surface, was to submit.

Television shows like Mad Men have brought home to today’s public how the pre-1960s closet had room for all manner of business besides being gay. Nonconforming domestic arrangements, partly abandoned old identities, and half-invented new ones were easier to keep out of sight. Thus Olive raised the Holloway- and Byrne-Marston children; Sadie shouldered much of the money-earning burden; Marston pursued experiments and self-help consulting. He ham-handedly publicized his expertise while eating and drinking enough to become roly-poly. If anyone asked, the story for the outside world was that Olive was a servant.

In a way, what’s more interesting about Lepore’s story is how the trio’s lack of traditional boundaries only began at home. We think of midcentury America as the time of a mass public, united in a popular culture, shepherded by hierarchical professions, and pushed toward consensus by newly authoritative experts. Lepore the flashpoint excavator does some of her best work conveying how the notions of credentialized expertise and the journalism needed to dispense all its wisdom were so new that a lot of it was made up on the fly.

It was the trio’s proximity to this game and its role-playing that led, in part, to Wonder Woman’s birth. Olive contributed for years to Family Circle magazine as the freelancer Olive Richard, using as the springboard for her articles a series of “visits” to the house of a renowned expert, Dr. Marston, to seek his advice. In one such article she asked him whether the new, addictive medium of comics was dangerous to children. Comics were virally successful, and they were provoking a mild panic over their potential impact on the young.

Again the parallel to debates of our time is striking. Within the past decade, entries in the Dark Knight Batman film series have sparked discussion about superheroes and the War on Terror, superheroes and the Occupy Movement, and whether Batman was reveling so much in the annihilation of villains that he risked exiting the moral world. Within two years of Superman’s launch in 1938, before the United States even contemplated entering World War II, a debate raged in Time about whether superheroes were fascist. (Writing in Library Journal, the poet Stanley Kunitz worried that comics would “spawn only a generation of Storm Troopers.”)

Dr. Marston reassured the Family Circle reporter that there was nothing worrying about children’s fascination with comics. Fantasies about besting the bad guys were understandable as wish fulfillment; the salacious presentation of people in danger was all right as long as they got rescued without lingering over anyone’s pain. Maxwell “Charlie” Gaines, founder of what would become DC Comics, saw the interview and thought Marston might be able to help him counter public-relations problems. With pronouncements Marston had made in the media over the years about the superiority of female leadership, it was a natural segue to thinking about how he might create a female superhero.

If Wonder Woman hadn’t arrived, it’s easy to imagine that someone else would have created a major superheroine around this same time. Circumstances—the new medium’s need for strategic moral cover, market opportunity, the national hunger for heroes—were urgently calling her into being. But Marston answered the call with forward-looking ideas about the secret psychological appeal and salutary social good of women’s strength. He also brought to the project his breadth of experience, a brazen declarative energy, and his own unselfconscious kink.

Like the fallout after a space collision, the details scattered into place. There was Marston’s hiring of veteran illustrator H.G. Peter, ancient by comics industry standards at the age of sixty-one, himself a suffrage sympathizer back in the day, classically fluent in standoffish, Gibson girl grace but up on Varga girl pizzazz. There was the famous lasso by which Wonder Woman compels a captive to do her bidding and, lie-detector-like, to spill the truth. Wonder Woman, undercover as Diana Prince, first as a nurse at Walter Reed Hospital, then working near her beloved American pilot Steve Trevor as a secretary in military intelligence, exclaims “Suffering Sappho!”—a nod to Sadie Marston’s adoration of the poet. (Another feminist angle: Steve’s preference for the muscular, omnicompetent heroine over her mousy counterpart.) Like Olive, Diana Prince is a freakishly fast typist. Also like Olive, Wonder Woman wears chunky metal bracelets, a version of which would soon become her best-known protector against enemy fire.

After laying out the why and how of her landing in America, Wonder Woman started out with fairly standard spy-catcher plots. Everywhere she turned there were enemy rings to break. Soon there were distinctive motifs and plot devices: enslaved or even reanimated agents of villains like the Baroness Paula Von Gunther sent cowering from their cellars to trick Steve Trevor or Wonder Woman, as well as more everyday scenes of the superheroine’s feminist bravado in a strength contest or a sports setting.

A mission from military intelligence might lead to a crime-solving caper at Holliday College and then a peek inside the offices of a puppet Hitler, controlled via “mental radio” by the vengeful Mars, aided by the astral-body projections of his Roman-headgear-wearing deputies the Earl of Greed and the Duke of Deception. (Sample caption, following a frame in which Hitler has been shown suffering an “attack of nerves”: “GIVING WAY TO A STRANGE IMPULSE WHICH AT TIMES POSSESSES HIM, HITLER BITES THE RUG, THEN SUDDENLY HIS WEIRD BRAIN RECEIVES THE MARTIAN RADIO MESSAGE.”) At times it feels like an affectionate parody of something that had once been more sane.

Nor is there any getting around the ever-present theme of—the obsession with—bondage. When Wonder Woman isn’t tied up, she’s rescuing someone else who is. Lepore notes that the often wordy Marston became strictly precise when instructing the illustrator which chains should go where:

Put another, heavier, larger chain between her wrist bands which hangs in a long loop to just above her knees. At her ankles show a pair of arms and hands, coming from out of the panel, clasping about her ankles. This whole panel will lose its point and spoil the story unless these chains are drawn exactly as described here.

Tim Hanley, an independent comics writer and the author of another recent book on Wonder Woman’s history, Wonder Woman Unbound, is less of an archive hunter than Lepore regarding the comic’s creators, but he has written a useful companion history that’s good at placing the character in the setting of her comic-franchise peers. His comparison on this question to other superheroes of the time finds Wonder Woman far and away the tie-up champion. “Bondage in Wonder Woman comic books was a vast and all-encompassing phenomenon,” he writes. Hanley also faces up to Marston’s creativity about ways to threaten and torture a bound person. (“Wonder Woman is embedded within a statue of herself or turned into a being of pure color, and prepped for boiling like a crayon.”)

On the other hand, it’s possible that this uncensored quality, with its frank appeal to fantasy, is what lends Wonder Woman her sincerity, her tenderness able to coexist with strength. Having thrown her lot in with America, she is intimate with and strictly supportive of our military goals. Yet ultimately she fights for the spread of love and peace, which are the moral core of her upbringing. Compassionate toward some of her misguided human foes, she takes an interest in their rehabilitation; in a Christmastime gloss on a typical plot of Nazis fleeing to Canada, Wonder Woman demonstrates not just an Amazon-trained facility with languages but her ability to commune with a gentle fir tree. As the singer Judy Collins points out in a foreword to the first volume of Wonder Woman: Archives, what was most amazing and inspiring to young girls encountering her in the 1940s was her sadly rare quality of being ethical.

Besides archives and comics Lepore relies on journalism, notebooks, letters, and traces of memoir left by the principals, as well as interviews with surviving colleagues, children, and extended family. Her discipline is worthy of a first-class detective. Still, one wonders if she doesn’t leave some themes underexplored. Lepore convinces us that we should know more about early feminists whose work Wonder Woman drew on and carried forward. But her portraits of figures like Annie Lucasta “Lou” Rogers, a suffragist cartoonist who led the way for women cartoonists and art directors at Judge and other major magazines, can feel too quickly rendered to take hold. A key spotter of connections, Lepore retrieves a remarkably recognizable feminist through-line, showing us 1920s debates about work–life balance, for example, that sound like something from The Atlantic in the past decade.

To the more mysterious question of why Wonder Woman had such an aesthetic pop, she brings a little less flair. And what if we want to know more about early feminist utopian fiction, and the art and ideas that nurtured it? Why did Amazon imagery come to dominate? What about the seeds of Aquarian ideas that would later reappear in New Age writings? These are part of the history; should today’s feminists feel responsible for knowing about them? (By the same token, should we feel embarrassed for forgetting the Theosophist underpinnings of L. Frank Baum’s The Wizard of Oz?) Finally, where is Marston’s mother? Her relative absence from the book hovers like a ghost in that Massachusetts castle.

Marston contracted polio in 1944, and then cancer; he died in 1947. Even while he lived, Wonder Woman’s strength was vulnerable to stewardship by other men. In 1942 she joined the Justice Society—the big leagues—to pursue supervillains with Superman and Batman. But that group franchise with its own joint comic book was headed by someone else, and in its plots she often got cast as the male heroes’ note-taker in dull meetings—a “secretary in a swimsuit,” Lepore nicely puts it. Over the decades, she would move through scenarios familiar to anyone already aware of how women were treated by the movies and television. For a while she would grow to care a little less about the world. By the late 1960s, she had surrendered many powers and settled for being a skilled fighter, all in order merely to date the pilot Steve Trevor—only to see him murdered, further narrowing her once world-historic purpose to avenging his death.

Those years, referred to as “the Diana Prince era,” are regarded as her nadir. By the end of the following decade Wonder Woman was for the first time the star of her own TV show. Until I read Lepore’s book I had no idea how fondly, if vaguely, I remembered watching that show as a child. Not that it was good or empowering. Apart from the theme song’s disco uplift, the memories are all visual, as if there were no plots or interplay between actors. There was the star Lynda Carter’s perfect black hair and corset-assisted superphysique; the then-fashionable owl-eye glasses she wore as Diana Prince; the comically cheap prop of her invisible plane; the gunmetal hair of Steve Trevor, played by Lyle Waggoner, a 1970s signifier of bland handsomeness who had been a straight man on The Carol Burnett Show. (It’s fitting that the forgettable Waggoner is more memorable here than Debra Winger, who briefly played the kid sister Wonder Girl.)

And of course there was the moment in every show where Diana would spin and transform herself into Wonder Woman. A cautious symmetrical whirl, it was too slow to suggest physical power. But there was something dumbly hypnotic about it. The young feminist artist Dara Birnbaum mixed dozens of spins from the show with explosions and siren sounds and spliced them all into a 1978–1979 video, Technology/Transformation: Wonder Woman. Today you can find mashups like it all over YouTube. For its time it was pioneering video art.

Wonder Woman has continued since, in comic-book form, through many regimes of writers and illustrators, and through several later story lines (with which I admit to being not very familiar) that have been far better received. But the fact that she has never been depicted in a live-action movie underlines Lepore’s point. If Wonder Woman is as recognizable a symbol as ever, outside the avid comics community there has been a gap between her fame and most people’s knowledge of what she’s been up to.

That will change in the spring of 2016 with the release of Batman v. Superman: Dawn of Justice, to be followed in a just-announced sequel, for 2017, by the first-ever stand-alone Wonder Woman movie. Wonder Woman will be played by the model Gal Gadot, like Lynda Carter a former beauty queen (Miss Israel), but unlike Carter a veteran of the Israel Defense Forces, so that her fighting can be expected to look more real, just as costume previews suggest that the bright old red, white, and blue will be traded in for a girdle of walnut and oxblood in line with today’s preference for materials at once more digitally perfectible and “naturalistic.” She will be strong and, at last, after all this time, the lead. Did she change the world? It’s hard to answer yes. But she was needed, and she has survived.

This Issue

November 20, 2014

Wake Up, Europe

Why Innocent People Plead Guilty