There’s a lot of money to be made in Africa, with its vast reserves of oil and gas, its abundant gold, diamonds, uranium, and other minerals, its timber, ivory, and fish. The ongoing Ebola epidemic in West Africa obscures the fact that the continent’s fast-growing population includes hundreds of millions of middle-class consumers with a taste for modern electronics, expensive clothes and other manufactured goods, as well as a need for pharmaceuticals and medical technology. These are the realities President Obama must have had in mind at last summer’s African Leaders Summit in Washington when he announced $33 billion in new US investment on the continent.

Most of the money will be directed at modernization. It will come from corporations like General Electric and in the form of loans backed by the government and World Bank, and will be spent on energy, construction, communications, and banking projects. In return, some investors probably hope to secure rights to extract and market Africa’s natural resources. Meanwhile, some one million Chinese restaurateurs, construction workers, oil drillers, mining engineers, fishermen, loggers, and prostitutes have also descended on Africa in the past decade. They too are competing for the continent’s riches.

“Africa is like a beautiful woman,” a Ugandan journalist told me when I asked him what he thought about all this economic activity. “She must choose among her suitors.”

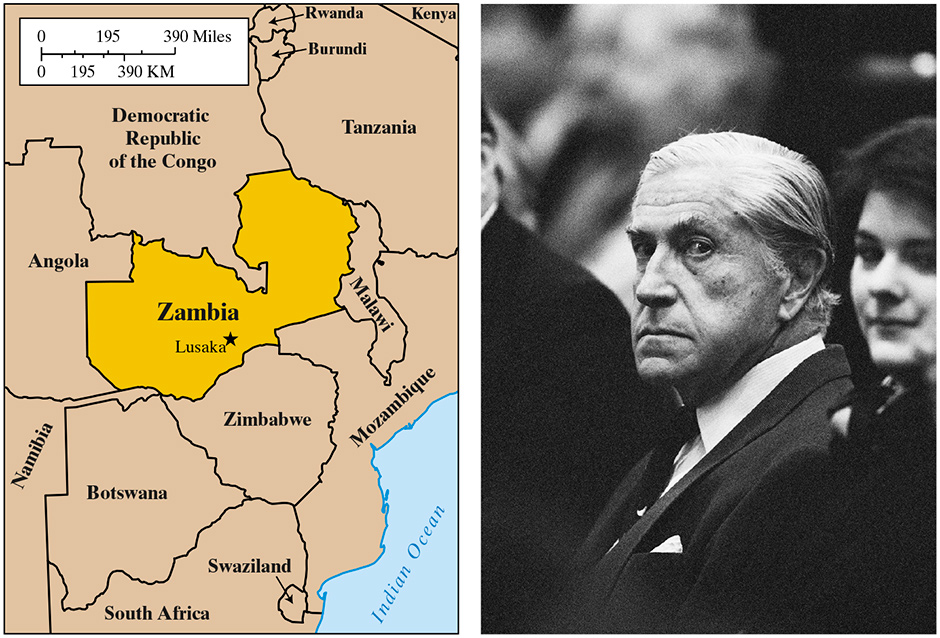

Several recent books about Zambia, a kidney-shaped Central African country known for its copper mines and game parks, suggest that this beautiful woman must also do more to avoid getting raped. Increased trade and investment are essential if Africa is ever to escape from poverty, but the continent still loses far more to corruption each year than it receives in foreign aid.1 The details of most of these scandals will likely be lost forever in a haze of complicated and unrecorded accounting tricks and whispered political promises. But these recent books provide telling details about coup plots and financial catastrophes that occurred there during and after the cold war, transforming what had been one of Africa’s most hopeful newly independent countries into one of the world’s most destitute.

Africans caught up in today’s scramble for their continent’s resources can be pretty certain that although the actors have changed, the play is much the same: as investment in Africa soars, foreign financiers and governments will no doubt continue to benefit from the continent’s vast but not limitless natural wealth, while shoring up allegiances with local leaders sympathetic to them. African people—most still poorly educated, preoccupied with tribal competition, and in the grip of corrupt dictators—need to strive for greater transparency and the rule of law in their countries before it’s too late.

On the eve of independence in 1964, 2 percent of Zambia’s 3.5 million people were white, but they controlled everything in a system resembling apartheid. In the lucrative copper mines, blacks were barred from management jobs, and had separate toilets and changing facilities. In the towns, blacks lived in separate neighborhoods, had separate cinemas, were banned from white areas after 5:00 PM without a pass, were forbidden to ride in the front passenger seat of a car driven by a white woman, and could not enter white shops but had to make purchases through a hatch in the wall.

Zambia’s first democratically elected president, Kenneth Kaunda—a gentle, teetotaling Christian, known for his love of ballroom dancing and for bursting into tears in the middle of his own speeches—took power in 1964 promising to build a new type of society based on equality. He inherited from his preacher father a gift for oratory, a belief in nonviolence, and an abhorrence of the indignity of discrimination. The slogan of his political party was chisokone, meaning “shake it,” writes Andrew Sardanis in Africa: Another Side of the Coin:

The response to the slogan was to raise your right hand in the air and twist it around fast, to indicate turbulence. The African arm is black and the palm is red. The shimmer of black and red from 100,000 hands waving chisokone was electrifying. It looked as if a bushfire was sweeping over the crowd.

The country Kaunda took over had fewer than a thousand black high school graduates and only three black doctors, three lawyers, and one engineer. The Zambian anchor of the evening news program could not pronounce “Philippines” or “Palestine” or understand the weather report. Nevertheless, the government built new roads, hospitals, schools, a university, hotels, and factories, and the economy boomed.

But trouble was already brewing. Kaunda, whose family had ethnic roots in what is now Malawi, struggled to balance the ambitions of Zambia’s roughly seventy tribes. Before long, civil servants came under pressure to give loans, grants, contracts, and jobs to members of particular ethnic groups and Kaunda loyalists instead of more qualified outsiders. Meanwhile, throughout the 1960s, left-leaning leaders—from Congo’s Patrice Lumumba to Uganda’s Milton Obote to Ghana’s Kwame Nkrumah—were toppled in coups sponsored by the US, Britain, France, and other Western governments. Kaunda managed to hang on to power for twenty-seven years, but in the process he sacrificed the nation’s political openness and its wealth. Much of the latter went to Tiny Rowland, a notorious British financier who exploited the African president’s insecurity.

Advertisement

During the 1960s, while other British businessmen were fleeing black-ruled African countries, Rowland’s London-based Lonrho conglomerate was buying up their mines, farms, and manufacturing plants. Meanwhile, Rowland himself, a former member of the Hitler Youth known as Roland Walter Fuhrhop, a man with a fixed smile and trademark silver suits, was also forming inordinately close, personal, and manipulative relationships with African leaders, including Kaunda.

Andrew Sardanis, a Greek Cypriot, moved to what is now Zambia as a teenager. He started a small trading business that delivered goods to and from the hinterlands. He slept in people’s huts, learned their languages, and joined their struggle for independence. He worked for the civil service in independent Zambia and eventually set up his own international banking and holding companies, the vicissitudes of which are described in one of his previous books, A Venture in Africa (2007). But early in his career, he briefly worked for Lonrho where he learned much about the company’s tactics.

When Sardanis arrived at Lonrho in 1971, its chief accountant handed him the records of the company’s African holdings.2 Right away, Sardanis realized something was amiss. Some Lonrho companies had no books at all; others were recording assets he knew they didn’t have. There were also a series of line items known as “investments in people”—bribes, mainly to African strongmen and the people around them.

Sardanis tried to talk to Rowland, but the magnate wasn’t interested in ledgers. Nor were Sardanis’s other Lonrho colleagues—smooth characters who seemed to do little except drop in and out of one another’s offices for chats. Some of these colleagues were former, and perhaps current, members of MI6 and other UK spy agencies; others were peripheral members of the British royal family. Sardanis’s only confidant was Rowland’s despised and ostracized accountant, who had been hired on the condition that he stay out of Rowland’s sight in a remote corner of the Lonrho office.

Six months after joining Lonrho, Sardanis submitted his resignation in disgust. He quit just in time. Later that summer, a South African stockbroker initiated criminal proceedings against Lonrho for misleading shareholders about the value of a copper mine in what was then Rhodesia (now Zimbabwe). Lonrho was also exporting copper from that mine in violation of UN sanctions against the white supremacist Ian Smith regime. Several members of Lonrho’s board of directors were beginning to ask questions about the “investments in people.”

One of the people Rowland invested in was Flavia Musakanya, wife of the governor of the Bank of Zambia. Shortly after the South African stockbroker launched his lawsuit, Rowland paid for Mrs. Musakanya’s medical treatment at a London hospital. When she was feeling better, he arranged for a chauffeur to drive her to Asprey, the Bond Street department store that among much else supplies jewelry and other accessories to the royal family. “I can’t afford this,” she told the chauffeur. “Don’t worry, just choose what you want,” she says he replied. “It will all be taken care of.” She chose to go back to the hotel, where the chauffeur presented her with an envelope stuffed with British banknotes. This she also refused. Years later she told Tom Bower, Rowland’s biographer, “Our relationship with Tiny was never quite the same again.”

Rowland wanted Flavia to agree that his problems in South Africa were the result of his anti-apartheid, pro-African nationalist views. In addition, he wanted to use his relationship to Kaunda to blackmail the South Africans into dropping their case against him. Zambia was a frontline state in the struggle against apartheid South Africa, and provided sanctuary to various liberation groups including the exiled African National Congress. Around the time of the trip to Asprey, the South Africans were trying to arrange a secret meeting between then Prime Minister John Vorster and Kaunda to discuss South Africa’s diplomatic isolation and fears that the ANC and other groups might stage attacks from Zambia.

A Lonrho executive privately informed the South African foreign minister that Rowland might use his influence to persuade the Zambian president to back out of the talks if the stockbroker’s case against Lonrho went ahead. A South African judge quietly dropped the case, the meeting between Vorster and Kaunda took place, and the infuriated stockbroker never connected the two events.

Advertisement

A year later, Kaunda came to Rowland’s rescue yet again when a group of furious Lonrho board members, desperate to rid themselves of their renegade boss, scheduled a shareholders’ meeting for May 1973 to vote on Rowland’s future at Lonrho. In the nick of time, the Zambian high commissioner in London wrote a letter warning that Lonrho’s Zambian assets would be nationalized if Rowland were removed. This so alarmed Lonrho’s shareholders that they voted to sack the board members and keep Rowland.

The Zambians had done much to save Rowland’s skin, but in his new book, Zambia: The First 50 Years, Sardanis reveals that the financier, for reasons Sardanis cannot explain, exacted a terrible punishment on the Zambian people nevertheless. As soon as the shareholders’ meeting was over, Lonrho began buying up bonds issued by Zambia’s copper mines. Sardanis found out about this from trader friends in London and warned Kaunda, who seemed unconcerned. Then, in August, Kaunda suddenly announced that he was nationalizing the copper mines. All bondholders would be paid in full, even though the bonds were currently trading at roughly a third of their face value. Kaunda’s reasons, enumerated in a long speech to the nation, made no sense to Sardanis, who suspected the hand of Rowland in its preparation. Even if Kaunda really thought nationalizing the mines was a good idea, which it wasn’t, the government could have bought the bonds slowly, at their trading value.

As a result of the move, Zambia would lose more than $200 million—roughly $1 billion in today’s money. Three weeks later, the Yom Kippur War of 1973 broke out, precipitating the OPEC oil embargo and the global economic crisis that sharply depressed the price of Zambian copper. By the late 1970s, Zambia had become one of the poorest, most indebted countries in the world. The expansion of schools and hospitals ground to a halt; women slept outside shops to buy food because it sold out by 9:00 AM.

Rowland’s manipulation of Kaunda is hard to understand, and Sardanis does not explain it. Kaunda was seen as an idealist, not a kleptocrat, and it’s unlikely that Rowland’s power over him was mere bribery. The truth of the matter may never be known. Rowland died in 1998 and Kaunda, now ninety, isn’t talking. However, Rowland was almost certainly either working directly for or was very close to British intelligence. It’s possible that he extracted financial favors from Kaunda in exchange for information. In 1980, Kaunda managed to foil an attempted coup. Piecing together the details of the plot from several of the books under review suggested to me that Britain might have been behind it, and that Rowland alerted him to it. This is speculation, but if true, it could help explain some of Kaunda’s more eccentric policy decisions, and serve as a warning to all Africans who wonder why their leaders don’t always act in their country’s best interest.

In 1980, nine Zambians, along with four Congolese mercenaries, were charged with plotting to overthrow Kaunda. Most of the Zambians were lawyers and businessmen and they had many grievances. During the 1970s, as Zambia fell into financial ruin, Kaunda entrenched his rule. In 1973, he banned political parties other than his own, which took over most functions of government from the cabinet, local government, and rubber-stamp Parliament. Spies posing as waiters eavesdropped on diners at restaurants, and newspapers confined themselves to singing the praises of Kaunda and his party.

Nearly all businesses—even dry cleaners—were nationalized by Kaunda’s one-party state. Leaders of banned opposition parties were arrested and beaten by mobs; many became destitute. They paced the streets in torn jackets and shabby shoes looking for work while less educated and able politicians of the ruling party drove around in limousines and sent their children to school in Europe.

Banker and businessman Goodwin Mumba was charged with corruption after giving some of these unemployed former opposition leaders small business loans. He was eventually acquitted, but lost his job anyway. He would go on to join the coup plot against Kaunda, as would Valentine Musakanya, husband of Flavia, who had by then quit the Bank of Zambia. He was deeply disillusioned with Kaunda’s leadership and said so publicly. In retaliation Kaunda revoked his passport, preventing him from taking up a lucrative job at IBM’s Paris office.

Zambia’s creditors were also exasperated with Kaunda, especially the mainly European banks that had lent the country money during its boom years. Unlike most countries impoverished by the 1970s debt crisis, Zambia had an asset: its copper mines. But as long as they were government-owned and inefficiently run by Kaunda’s cronies, the banks weren’t going to get much out of them.

The story of the plot itself is told in considerable detail by Sardanis, by historian Miles Larmer in his recent book Rethinking African Politics, and also by coup plotter Goodwin Mumba himself in his book The 1980 Coup: Tribulations of the One-Party State in Zambia. But even Larmer, a scholar with deep knowledge of Zambia’s history, admits that the details remain shrouded in “rumour and myth, claim and counterclaim.” Particularly murky is the origin of the roughly $250,000 that was used to finance the plot.

According to Mumba, the funds came from an Arab sheikh who wanted to invest in a Zambian hotel that had been nationalized by Kaunda. Mumba describes a trip that he and Musakanya took to France to collect a suitcase stuffed with banknotes from this sheikh in a Paris hotel room. On the way home, they stopped in London where Musakanya became worried about crossing the Zambian border with so much cash. He suggested they visit Sardanis, Musakanya’s old friend from the independence struggle, who was then running various African businesses from London. Perhaps he’d be willing to deposit the money in his own account and then write the Zambians a check in kwacha, the local Zambian currency.

At dinner that evening, Musakanya handed over the suitcase and Sardanis handed over a check. In a moment of drunken bravado, Musakanya had told Sardanis what the money was to be used for. Mumba believes that Sardanis then informed Kaunda, and from then on the plotters were under surveillance and were eventually caught. Musakanya spent five years behind bars and Mumba ten. In return, says Mumba, Sardanis’s companies were granted lucrative contracts for the procurement of mining and farm machinery in Zambia.

In his own book, Sardanis denies this entire account and says he had nothing to do with the coup plot, the money, or Kaunda’s discovery of it. He thinks the money came from South Africa, which would have had obvious motives for wanting to depose the leftist, anti-apartheid Kaunda.

On a visit to Lusaka last April, I met Mumba. Now nearly eighty, he’s an elegant, articulate man, but the story about the sheikh and the suitcase seemed unconvincing to me too. On the flight over, I’d watched the film American Hustle, a fictionalized account of the FBI’s Abscam operation. In the film, and in real life, several New Jersey politicians accept bribes from an Arab sheikh who says he’s interested in investing in Atlantic City casinos. In some cases, the money is handed over in briefcases in hotel rooms. The sheikh turns out to be a keffiyeh-garbed Hispanic undercover agent and the politicians all go to jail.

I wondered about this. American Hustle is based on events that occurred in the late 1970s, around the same time as the Zambian coup plot. After the OPEC oil embargo, mysterious Arabs in long robes were buying up the best real estate in London, New York, and Paris and sweeping through the aisles of fashionable shops in Knightsbridge and the Faubourg St. Honoré. Rumors about what they were up to swirled around the globe. It probably didn’t take much imagination for intelligence operatives to invent stories about their underhanded financial dealings as a cover for the operatives’ own.

“Is it possible,” I asked Mumba, “that British intelligence was behind your coup?”

Mumba laughed. “Yes, you are quite right.”

It turns out that Valentine Musakanya was recruited into MI6 while studying at Cambridge in the 1950s. Until his death in 1995, he remained on friendly terms with Daphne Park, an MI6 agent who was stationed in newly independent Congo during the early 1960s. Shortly before her death in 2010, she confessed to David Lea, a member of the House of Lords, that she had a hand in organizing the 1961 assassination of Patrice Lumumba, Congo’s leftist first prime minister, presumably in collaboration with Belgium and the CIA. The West feared that Lumumba would align Congo with the USSR, jeopardizing access to its vast gold, diamond, and uranium mines.

Lumumba’s murder was carried out by a separatist group based in the province of Katanga where many of these mines were located. A few months after Lumumba’s death, Musakanya was posted to the British consulate in Katanga, where he befriended members of this separatist group. Years later, some of those same Katangese separatists—including Albert Chimbalile, who according to testimony described by Mumba personally tortured and killed Lumumba—served as mercenaries for the aborted 1980 coup in Zambia.

In other words, in Zambia, as in Congo, the West may well have been hoping to install a leader sympathetic to its desire for control of natural resources, in this case, copper. But if so, who exposed the plot to Kaunda? Mumba claims that Sardanis did, but Mumba’s book—which fails to mention MI6—isn’t entirely accurate, and Sardanis denies knowing of the plot in advance. One possibility is that Kaunda found out from his old friend Tiny Rowland, who might well have learned about it through contacts in MI6. There’s no way to know for certain, but it’s worth noting that Rowland continued to profit from his relationship with Kaunda—despite the bond-purchase fiasco—right up until the Zambian president stepped down in 1991. During the 1980s, Lonrho became the exclusive buyer of Zambian amethysts. When Zambian miners protested that the company paid well below market price and customs agents complained that Lonrho illegally paid no duty, President Kaunda did nothing.

If Kaunda did grant Rowland favors in exchange for information about Britain’s efforts to undermine him, the president’s motivation might not have been merely self-interested. The coup leaders, who played tennis and hatched their plot at the Lusaka Flying Club, were from a patrician tribe and class. Had they taken over, there’s no telling how the people of this diverse country might have reacted, but many would certainly have been unhappy. As the sad history of so many other African countries shows, the risk of violence and chaos was real. Kaunda held the country together and prevented bloodshed, despite the meddling of cold war powers. If he did so at the expense of the nation’s riches, that may have been his only choice.

After the cold war ended, Zambia, like most African countries, finally allowed elections and carried out neoliberal reforms including privatization of all industries and relaxed currency controls in line with World Bank and International Monetary Fund recommendations. But these reforms proved no panacea for the nation’s economic difficulties. As happened in many other African countries and throughout Eastern Europe, well-connected officials in collaboration with foreign companies robbed the Zambian people—again and again—of billions of dollars in lost taxes and royalties and undervalued privatization schemes, while the IMF and World Bank, which were supposed be the nation’s financial advisers, did nothing.

The most notorious of these scandals occurred during the presidency of Frederick Chiluba, who would become famous for his vast collection of multicolored platform shoes, gold bracelets, and illegally acquired property in Europe. The gory details of some of these scandals can be found in Sardanis’s books, but the important point is that this blatantly self-interested corruption continues, and threatens to tear the country apart.

Remarkably, some ordinary Zambians have managed to prosper despite these upheavals. Some buy and sell goods in South Africa and Dubai, others work in the informal transportation industry, others grow and sell food. But millions remain on the edge of subsistence in a society without adequate legal protection, accountability, and, increasingly, hope. Sardanis notes the emergence of potentially violent separatist movements. Thus, the country’s fate depends upon greater financial transparency and the rule of law. President Michael Sata, who died in late October, tried to investigate and reverse some of the corruption-related abuse of his predecessors, but he also intimidated and imprisoned critical journalists and opposition politicians and failed to adopt a promised new constitution. An election to replace him is scheduled for January 2015, but given the complexities of managing the ongoing scramble for the nation’s wealth, it will take a very special Zambian to hold the country together and avoid the twin temptations of looting and repression.

Sardanis, now in his eighties, runs a game reserve near Zambia’s capital, Lusaka. It practices the ecological harmony he must have envisioned in his adopted country when he arrived sixty-five years ago. There’s a lake with exotic birds and fish and grasslands with strangely placid wild animals. You can walk right up to the elephants and even cuddle the cheetahs. In the main house, there’s a remarkable collection of African art, including traditional masks with feathers, teeth, and horns, meant to symbolize the wearer’s anger at the intruders who invaded this land during colonial times, and threaten it still.

-

1

“The Trillion-Dollar Scandal,” a report by the One Campaign, September 3, 2014. ↩

-

2

The following account is drawn from Tom Bower’s Tiny Rowland as well as Sardanis’s Africa: Another Side of the Coin and Zambia: The First 50 Years. ↩