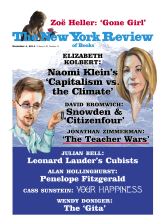

Equal Justice Initiative/John Earle

Bryan Stevenson with his colleagues at the Equal Justice Initiative in Montgomery, Alabama, including senior attorney Charlotte Morrison (center row, second from left), as well as with two of his clients: Jesse Morrison (top left), who won a reduced sentence after serving nineteen years on death row for a murder conviction in which the prosecution had eliminated all but one of the black jury candidates; and Jerald Sanders (bottom left), who won his release after serving twelve years of a sentence of life without parole for the nonviolent crime of stealing a bicycle. Also pictured is a tower at Holman State Prison, Alabama’s main death row.

1.

In Harper Lee’s To Kill a Mockingbird (1960), an innocent black man, Tom Robinson, is falsely accused of raping a white woman in a small 1930s southern town not unlike Lee’s hometown of Monroeville, Alabama. Robinson is tried and convicted by an all-white jury, despite the best efforts on his behalf of Atticus Finch, a white lawyer who defies the town’s lynch-mob mentality and demonstrates at trial that the victim’s story is false. Robinson tries to escape, and is shot in the back and killed. The book’s considerable dramatic power derives in part from its raw story of racial injustice, but also from the author’s choice of an innocent narrator, Atticus Finch’s young daughter, Scout.

Bryan Stevenson’s Just Mercy tells the story of an innocent black man from the real Monroeville, Alabama, wrongly accused and convicted of a violent crime against a young white woman, although in this case the crime is murder, and this time the story is nonfiction. Stevenson’s account of the trial and appeals of Walter McMillian takes place in the 1980s and 1990s, not the 1930s. But some things apparently do not change. McMillian, like his fictional counterpart Robinson, had committed the ultimate southern sin of having relations with a white woman, and he may have been singled out for prosecution in part because his affair had rendered him suspect and dangerous in the eyes of Monroe County’s white community.

Instead of Atticus Finch, the legal part in this story is played by Stevenson himself, a young African-American who grew up in rural and segregated Delaware, graduated from Harvard Law School, and founded the Equal Justice Initiative, a nonprofit law office in Alabama, to provide legal assistance to the many unrepresented men on death row there. Stevenson is today, along with his mentor, Stephen Bright, one of the nation’s most influential and inspiring advocates against the death penalty. He and his EJI colleagues have obtained relief for over one hundred people on Alabama’s death row, and won groundbreaking Supreme Court cases restricting the imposition on juveniles of sentences of life without parole. Unlike Finch, Stevenson won his client’s case. After extensive investigation, he proved that the scant evidence offered at trial against McMillian was all false, much of it coerced out of hapless “witnesses” by a sheriff and prosecutor who needed to pin the unsolved murder on someone.

Just Mercy is every bit as moving as To Kill a Mockingbird, and in some ways more so. Although it reads like a novel, it’s a true story and, in that sense, is infinitely more troubling. It’s set not in the distant Jim Crow South, a time when we now acknowledge these kinds of injustices were legion, but in the new South, which claims to have moved on. And while Stevenson’s account is not as naive as Scout’s, he brings to its telling a faith in the human spirit that, like Scout’s narrative, casts in sharp relief the cruel injustices they relate.

Just Mercy demonstrates, as powerfully as any book on criminal justice that I’ve ever read, the extent to which brutality, unfairness, and racial bias continue to infect criminal law in the United States. But at the same time that Stevenson tells an utterly damning story of deep-seated and widespread injustice, he also recounts instances of human compassion, understanding, mercy, and justice that offer hope. Just as the reclusive Boo Radley teaches Scout Finch about the human spirit’s potential for compassionate action, so many of the people that Stevenson encounters along the way—clients, family members, crime victims, and even a prison guard—offer glimpses of humanity’s better side. As a result, Just Mercy is a remarkable amalgam, at once a searing indictment of American criminal justice and a stirring testament to the salvation that fighting for the vulnerable sometimes yields.

Walter McMillian’s troubles began the morning of November 1, 1986, when Ronda Morrison, an eighteen-year-old white college student working at Monroe Cleaners, was shot in the back and killed. The crime understandably shocked the sleepy town of Monroeville, and when the authorities were unable to identify the killer after several months, public criticism mounted. When they interrogated Ralph Myers, a white drug dealer, for another murder, he sought to point the finger at others. After Myers’s first two stories proved completely false, he offered a third, claiming that Walter McMillian had killed Morrison.

Advertisement

Myers’s account of the Morrison murder was highly implausible. He claimed that McMillian, whom he did not know, had accosted him the morning of the murder at a gas station outside Monroeville, forced him at gunpoint to drive McMillian to Monroe Cleaners, and then ordered him to wait outside. According to Myers, when McMillian emerged from the cleaners and returned to the truck, he admitted to killing the woman inside, and then returned Myers to the gas station so that Myers could retrieve his own car. Apparently no one thought to ask why someone planning a robbery would abduct someone he didn’t know to drive his own truck, trust him to remain outside while he went in, admit upon returning to the truck that he had murdered someone, and then let his captive go.

The police arrested McMillian in June 1987. Shortly thereafter, Myers recanted his unlikely story, admitting that he had made it all up. The authorities responded by imprisoning both Myers and McMillian on death row, a section of prison that by law is restricted to convicted defendants sentenced to death, not pretrial detainees, who are presumed innocent. The morning after an execution, a shaken Myers called the sheriff, agreed to recant his recantation, and became the state’s principal witness against McMillian. When Myers had second thoughts yet again shortly before trial, he was returned to death row until he agreed to finger McMillian. Over the defense’s objection, the prosecution got the trial transferred to a neighboring county whose population was overwhelmingly white, and then struck from the jury all but one black juror.

No physical evidence linked McMillian to the murder. In addition to Myers, the state offered a witness who claimed to have seen McMillian’s “low-rider” truck in front of the cleaners the morning of the crime, and another man who also claimed to have seen McMillian’s truck in the vicinity of the crime. (In fact McMillian’s truck had not been transformed into a “low-rider” until six months after the Morrison murder.) The defense put on three witnesses who had been at McMillian’s home the morning of the murder for a church fish fry, each of whom said that McMillian had been there all morning long. The nearly all-white jury convicted McMillian, and voted for a life sentence. The presiding judge, Robert E. Lee Key, overrode the jury, and sentenced McMillian to die.

When Stevenson first took on McMillian’s appeal, he received a call from Judge Key, who asked him, “Why in the hell would you want to represent someone like Walter McMillian?” Judge Key claimed McMillian was a notorious drug dealer, and maybe even part of the “Dixie Mafia.” The judge told Stevenson that he wouldn’t authorize him to handle the appeal, as is necessary when a lawyer from out of state seeks to practice in another state’s court. When Stevenson replied that he was admitted to practice in Alabama and therefore didn’t need permission, the judge responded that he wouldn’t authorize payment of his attorney’s fees by the state. When Stevenson explained that he worked for a nonprofit and wasn’t seeking fees, the judge hung up on him.

During the next several years, Stevenson and his colleagues at the EJI thoroughly reinvestigated McMillian’s case. In the end, all three of the state’s witnesses, including Ralph Myers, admitted that they had lied on the stand. Stevenson also discovered that the prosecution had illegally failed to turn over to McMillian’s trial lawyers crucial exculpatory evidence, including six statements from Myers himself, typed up by the prosecution, in which he admitted that the story he ultimately told at trial was a lie, and that he knew nothing about the Morrison murder. Notwithstanding such overwhelming evidence, the trial judge denied Stevenson’s motion for a new trial in a cursory two-and-a-half-page order.

The evidence Stevenson had unearthed, however, prompted a 60 Minutes story and other national attention. When the prosecutor then requested his own investigators to reexamine the case, they concluded, as they told Stevenson, “There is no way Walter McMillian killed Ronda Morrison.” Six weeks later, the Alabama appeals court reversed McMillian’s conviction and death sentence, and shortly thereafter, the state dismissed all charges. McMillian had spent six years on death row for a crime he did not commit. He lived the rest of his days a free man, although continually haunted by his years on death row. One of the book’s saddest moments comes when Stevenson visits McMillian in a nursing home, where McMillian, suffering from dementia, imagines that he is back on death row and implores Stevenson to free him once again.

Advertisement

2.

McMillian’s case is not an aberration. Stevenson recounts several other cases alongside his unraveling of the case against McMillian, and the effect is to present a panorama of systemic injustice and callous indifference to human suffering. Some of the most disturbing stories concern children tried and convicted as adults for crimes committed as juveniles. There is Charlie, who at age fourteen shot and killed his mother’s boyfriend, after the boyfriend had come home drunk, again, and beat Charlie’s mother, again. This time, he punched her in the face so hard that she passed out, hitting her head on the kitchen counter as she fell.

Charlie, a good student with no criminal record, was left to care for his unconscious mother, bleeding profusely from her head, while the boyfriend went to the bedroom and passed out on the bed. When Charlie went into the bedroom to get the phone to call 911, he first picked up the boyfriend’s gun and shot him. The state sought to prosecute Charlie as an adult, perhaps because the boyfriend was a police officer. It held him in an adult jail, where he was repeatedly sexually abused. Stevenson took on his case and got it transferred back to juvenile court, where Charlie would be eligible for release when he became an adult.

Or consider Trina Garnett, the youngest of twelve children of a violent alcoholic father, from one of Pennsylvania’s poorest towns. Some of her brothers and sisters were conceived when Trina’s father raped her mother. When Trina was nine her mother died and her father started sexually abusing Trina and her siblings. She and her sisters ran away from home and ate out of garbage cans. One night when Trina was fourteen, she and a friend climbed through the window of the home of two boys they knew. Trina lit a match to guide them in the dark, the house caught fire, and the boys died of smoke inhalation.

She was tried as an adult and sentenced to a mandatory term of life without parole, even though the judge found that she had no intent to kill. Sent to an adult prison, Trina was raped by a guard and delivered a baby boy while handcuffed to a bed. Her son was sent to foster care. Today, at fifty-two, she remains incarcerated, despite Stevenson’s victory in a related case, Miller v. Alabama, in which the Supreme Court ruled that it is unconstitutional to impose mandatory life without parole sentences on juveniles.

In almost every case Stevenson takes on, the defendant has been convicted of murder. Yet in every instance, he insists that we look beyond the bare facts of the crime and pay attention to the human being who committed it. There are virtually always mitigating circumstances—abusive parents, serious mental disabilities, addictions, abject poverty. In each case, no matter how hideous the crime, Stevenson finds some glimmer of humanity. As he maintains, no one is as bad as the worst thing he has ever done. It is that insight that makes his book not just maddening, but inspiring. Stevenson refuses to give up on his clients, and asks the same of us.

One of the book’s most moving stories concerns Avery Jenkins. Jenkins’s letters to Stevenson from death row suggested that he was suffering from serious mental disabilities. When Stevenson first went to meet Jenkins, a surly white prison guard demanded that Stevenson submit to a strip search before entering the prison—unheard of for attorney visits—and boasted that he was the owner of the truck in the parking lot bearing a bumper sticker that read, “If I’d known it was going to be like this, I’d have picked my own damn cotton.” Jenkins wanted only to know if Stevenson had brought him a chocolate milkshake—a request repeated every time they met. Stevenson was able to get Jenkins to answer any questions only by promising to try to bring him one the next time, even though the prison authorities never permitted it.

Jenkins’s father was murdered before he was born, and his mother died of a drug overdose when he was one. He had been in nineteen different foster homes by the time he turned eight. At age ten, his foster parents locked him in a closet, denied him food, and beat him when he violated their rules. At one point, his foster mother took him into the woods, tied him to a tree, and left him there. Hunters found him three days later. At thirteen, he was addicted to drugs. At fifteen, he was having seizures and psychotic episodes. At seventeen he was homeless. At twenty, he stabbed and killed an elderly man during a psychotic episode.

Stevenson presented this evidence at Jenkins’s post-conviction hearing, arguing that his trial lawyers’ failure to offer any of this evidence was ineffective assistance of counsel. The racist prison guard was there, having driven Jenkins the three hours from prison to court. When Stevenson next visited Jenkins, the guard could not have been more polite. Stevenson was mystified, until the guard explained that he, too, had been repeatedly abused in foster homes: “I didn’t think anybody had it as bad as me…. But listening to what you was saying about Avery made me realize that there were other people who had it as bad as I did. I guess even worse.” Driving Jenkins back to the prison after that hearing, the guard took an unauthorized detour to buy him a chocolate milkshake.

It is in such moments of connection that Stevenson finds hope. Only the absence of empathy can explain our nation’s unremittingly harsh approach to criminal justice. We are the undisputed world leader in incarceration. We are alone among the developed world in still putting people to death. And nowhere in the world have more children been sentenced to die in prison for crimes they committed as teenagers. For forty years, beginning in the 1970s, incarceration rates steadily increased as we built more prisons, imposed longer sentences, and launched a “war on drugs” that relegated hundreds of thousands to prison for nonviolent offenses often driven by poverty and addiction. Legislatures abolished parole and gave up on rehabilitation. As Stevenson might put it, we have chosen to treat people as if they are as bad as the worst thing they ever did. We hate not only the sin, but the sinner. For a putatively religious country, we seem to have forgotten one of the central lessons of all religions, and certainly the central message of Stevenson’s work—that every human being is capable of redemption.

3.

As with individuals, so with societies: it is never too late for redemption. And there are promising signs that the tide is finally beginning to turn in American criminal justice. The national per capita incarceration rate (combined state and federal prisons) reached an all-time high in 2007, but has fallen each year since then. Last year, the number of federal prisoners fell by 4,800, the first decline in about four decades. It is expected to drop by another 12,000 over the next two years. That’s the equivalent of closing six prisons. And progress has been more dramatic at the state level, where most criminal law enforcement occurs. As the authors of The Growth of Incarceration in the United States write, “between 2006 and 2011, more than half the states reduced their prison populations, and in ten states the number of people incarcerated fell by 10 percent or more.” In recent years, states have reduced or eliminated mandatory minimum sentences, repealed “three-strikes” laws that impose life sentences on repeat offenders, and decriminalized marijuana possession.

For decades, the only conceivable position for most politicians on crime was to be tougher than their opponent. As a presidential candidate, then Governor Bill Clinton returned to Arkansas in 1992 to oversee the execution of Ricky Ray Rector, a man who had lobotomized himself in an attempted suicide after shooting a police officer. As president, Clinton signed the Anti-Terrorism and Effective Death Penalty Act of 1996, which erected stringent barriers to state prisoners seeking relief for unconstitutional convictions.

By contrast, today the Obama administration, largely through the leadership of Attorney General Eric Holder, has made it a top priority to reduce our nation’s reliance on incarceration. Holder has argued that it is better to be “smart” than “tough” on crime and that current criminal sentencing laws and policies are too harsh. He supported a reduction in federal sentencing guidelines for low-level drug offenders and ordered US attorneys to stop charging such offenders with crimes that carry severe mandatory minimums. That the nation’s leading law enforcement officer has been willing to press such reforms is as much a sign of the country’s changing attitude toward criminal justice as it is a testament to Holder’s commitment.

Criminal policy used to be a wedge issue that Republicans exploited to draw conservative Democrats to their party. Today, criminal law reform is one of the few initiatives on which one finds bipartisan agreement in Washington. Republican Senators Rand Paul, Jeff Flake, Ted Cruz, and Mike Lee, as well as Representatives Frank Wolf and Paul Ryan, have all joined Democratic legislators in calling for reduced federal mandatory sentences.

Similar thinking is reflected in The Growth of Incarceration in the United States, a 2014 National Academies report reflecting the views of a blue-ribbon committee of the nation’s leading criminology scholars. It found that longer criminal sentences are unlikely to have much effect on crime. Studies show that people are much more likely to be deterred by the certainty of punishment than by the length of sentences. And because the commission of crimes drops off sharply with age, holding older people in prison is unlikely to have much effect on crime. The committee called for reductions in criminal sentences and increased use of alternatives to incarceration.

Jonathan Simon’s Mass Incarceration on Trial is yet another sign of the new optimism about criminal justice reform, but in this case, the optimism goes too far. Simon focuses on a decades-long litigation campaign challenging the inadequate provision of medical services to California state prisoners. Federal courts ruled in the late 1990s and early 2000s that California was failing to meet its constitutional obligations of care. After many years trying unsuccessfully to enforce a remedy, the courts concluded that the problem could not be resolved unless California reduced its overcrowding. At the time, its prisons held about double their capacity; the court ordered the state to reduce the population to 137.5 percent of capacity, a remedy that would require releasing or transferring some 40,000 prisoners in the absence of new prison construction.

In 2011, in Brown v. Plata, the Supreme Court affirmed that remedy by a 5–4 vote. Simon sees this victory as the beginning of the end of mass incarceration. As he puts it, “if the physical and mental health requirements of prisoners cannot be constitutionally met on a mass scale, then mass incarceration is inherently unconstitutional.” I wish he were correct, but I fear that he is not.

The Court held only that when courts have tried for more than a decade to remedy an ongoing constitutional violation, and conclude that the remedy cannot be achieved unless overcrowding is reduced, it is then permissible to order such a drastic remedy. But that is a far cry from declaring mass incarceration unconstitutional. The problem the Court identified was not mass incarceration but overcrowded prisons with inadequate services. In theory, California could have responded to the order by building more prisons. And as long as states provide minimally adequate medical care, the Brown decision poses no barrier to mass incarceration.

Simon also argues that Brown establishes that prisons must respect prisoners’ dignity and that

imprisoning people to achieve general incapacitation, with no concern for individual criminal history or risk, denies their humanity. A prison system organized on that basis cannot preserve the human dignity of its prisoners.

But Brown addressed only the adequacy of medical care in California’s exceptionally overcrowded prisons, not the permissible purposes of punishment. And in any event, Simon has not shown that any prison system, even California’s, locks up people with “no concern for individual criminal history or risk.” Nothing about mass incarceration implies, much less requires, that the state disregard criminal history or risk altogether.

More fundamentally, Simon’s focus on courts as the source of a solution seems unrealistic. He notes, correctly, that prisoners are politically powerless, and are therefore especially deserving of judicial protection. But mass incarceration is largely the result of constitutionally permissible, if deeply misguided, policies about how harshly to respond to crime. The courts have long abjured any real oversight of those questions. More generally, courts tend not to lead but to follow reform movements. Brown v. Plata is encouraging not for its narrow and fact-specific legal ruling, but for what it reflects about broader cultural attitudes. That five justices were willing to uphold a remedy that could result in the release of 40,000 prisoners is yet another sign of growing skepticism about harsh incarceration policies.

But we ought not mistake a sign of change for its cause. If mass incarceration is to end, it won’t be because courts declare it unconstitutional. It will instead require the public to come to understand, as the National Academies report found, that our policies are inefficient, wasteful, and counterproductive. And it will require us to admit, as Bryan Stevenson’s stories eloquently attest, that our approach to criminal law is cruel and inhumane. Mass incarceration is one of the most harmful practices we as a society have ever adopted, but as Stevenson would say, we are all better than the worst thing we have ever done.