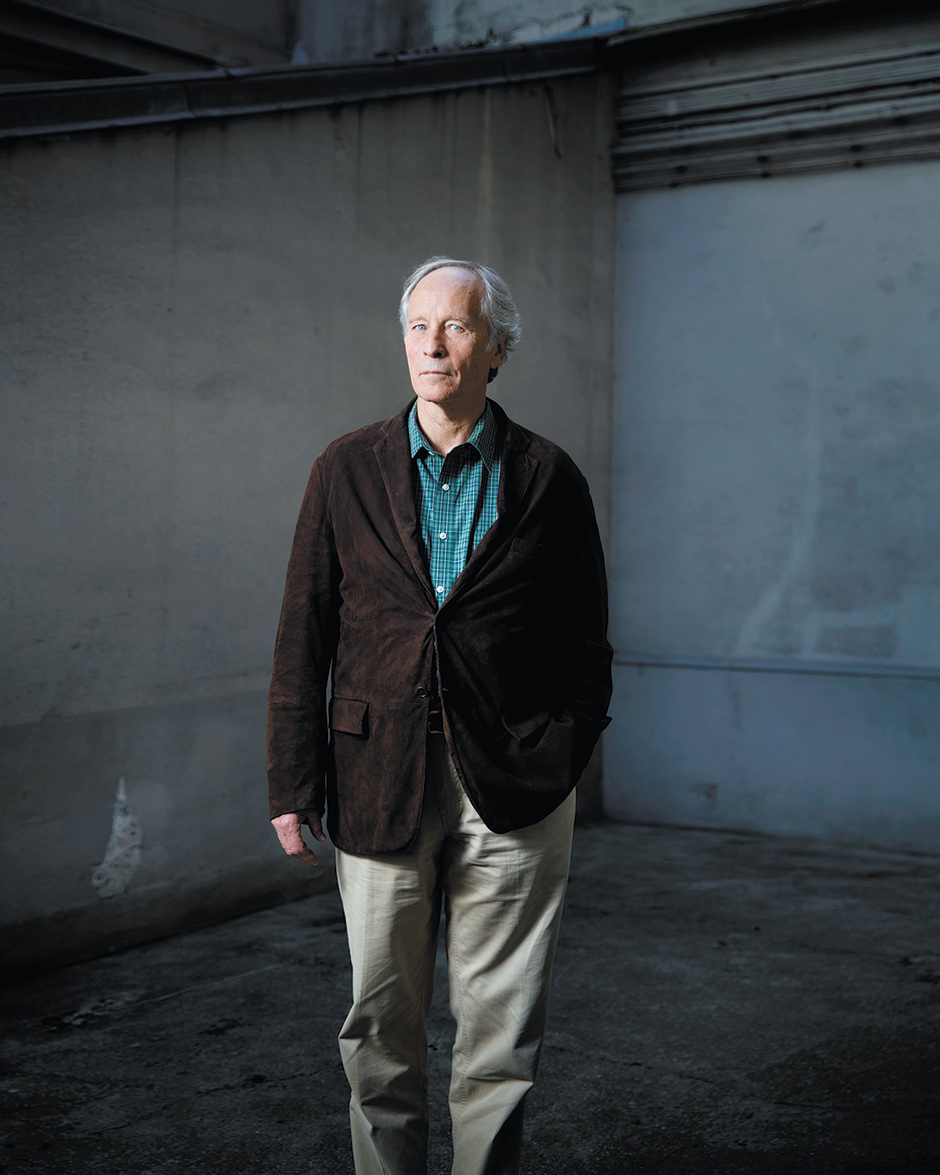

Apart from the seemingly silly title, Richard Ford’s new collection of four long stories about Frank Bascombe is pure pleasure. In fact, even that punning phrase “Let Me Be Frank With You” can be grudgingly justified since each story soon evolves into an intense two-person conversation: after a period of hesitation, a series of people end up being—more or less—frank with Frank. Somewhat more faintly, the title also implies Bascombe’s insistence on being accepted for who he is. The failed novelist, former sportswriter, and now retired sixty-eight-year-old realtor has settled into a certain melancholy ease with himself.

Such titular tricksiness might seem far-fetched except that Richard Ford never writes an unconsidered word. Without being froufrou in the least, he’s extraordinarily attentive to diction and tone. In fact, what makes Ford’s new book particularly remarkable must be how little happens in it—and how little we miss the usual Sturm und Drang of plot or fast-paced action. Because Frank Bascombe’s voice on the page is so utterly ingratiating, so Sinatra-like smooth and easygoing, we are happy just to listen to him ruminate (and occasionally moralize). Like V.S. Naipaul in The Enigma of Arrival—a book the ex-realtor is reading to the blind—Frank is absorbed in the small quotidian pleasures and consolations of his “end-of-days’ time, known otherwise as retirement.” To those of his age, he concludes, “life’s a matter of gradual subtraction, aimed at a solider, more-nearly-perfect essence.” While that sounds like cold comfort, a “nearly-perfect essence” is nonetheless what Ford, aged seventy himself, has achieved in this lean and lovely book.

Years ago in an interview, Ford remarked that the Pulitzer Prize–winning Independence Day (1995)—the second of his three Frank Bascombe novels, the others being The Sportswriter (1986) and The Lay of the Land (2006)—was about “the eventual sterility of cutting yourself off…from attachments, affinities, affiliations with other people.” Not surprisingly, then, Ford’s best fiction regularly explores the consequent search for connection, for those silent intimacies that bridge human loneliness. Though wary and cautious, Frank Bascombe has always been a tough-minded optimist. He has survived the death of a young son, a traumatic divorce, prostate cancer, and myriad other sorrows. He has come through. His “life-long dream,” he tellingly notes here, “is to visit the Alamo—proud monument to epic defeat and epic resilience.”

These days Frank appears almost saintly, though he would blanch at that word. Besides reading aloud to the blind, he travels each week from his home in Haddam, New Jersey, to Newark Liberty Airport to welcome back servicemen and women from “wherever our country’s waging secret wars and committing global wrongs in freedom’s name.” He also contributes a column called “What Makes That News?” to the vets’ magazine, We Salute You. Not least, each month he faithfully visits his ex-wife Ann, now suffering from the early symptoms of Parkinson’s disease and residing in “a staged extended-care community” named, of all things, Carnage Hill. While Frank makes light of these acts of charity and love, how many of us would do half as much? Even his wife Sally volunteers as a counselor to grieving families who lost their homes and belongings in the wake of Hurricane Sandy.

In late October 2012, Sandy swept along the Jersey Shore, wreaking widespread destruction and totally destroying Frank’s former beach house at Sea-Clift. Fortunately for him, he had sold the place eight years earlier to the wealthy fish magnate Arnie Urqhart. Still, the hurricane’s devastation, both physical and psychological, has left its scars. Many people seem to be asking, “How should I go on with the rest of my life now that I’ve experienced all this?” Frank has dealt with this very question more than once himself and the possible answers to it are what fascinate Ford. He has long been a chronicler of aftershocks, a novelist drawn, in his own words, to “what happens after the bad things happen…because it’s a proving ground for drama.”

Just as the earlier Bascombe books took place in, successively, the run-ups to Easter, the Fourth of July, and Thanksgiving, so this one is set in the final two weeks before Christmas 2012. In “I’m Here,” Arnie Urqhart asks Frank to come down to the shore for a final look at what’s left of the house these two aging men once owned. It hardly takes a medieval allegorist to perceive that Arnie’s story, and the three that follow, establish an analogy between people and telltale symbolic buildings: a destroyed beach home, a suburban house with a haunted past, a sleek apartment in an ultramodern nursing facility, a once fabulous but now dilapidated mansion. When Frank remarks that “a career selling houses lets you know you can live with a lot less than you think,” he’s not just talking about downsizing your residence. Old age, as he has told us, is a matter of gradual subtraction.

Advertisement

While Frank typically casts a cold eye on life and death, being Frank he still remains funny and impassioned. He notes, for instance, that

a surprisingly large segment of our Haddam population (traditionally Republican; recently asininely Tea Party) believes the president either personally caused Hurricane Sandy, or at the very least piloted it from his underground “boogy bunker” on Oahu, to target the Jersey Shore.

Frank’s own values are nonetheless solidly bedrock, traditionally American. En route to the fatal shore, he automatically inserts a CD of Aaron Copland’s Fanfare into the player of his Hyundai Sonata:

As always, I’m stirred by the opening oboes giving ground to the strings then the kettle drums and the double basses. It’s a high-sky morning in Wyoming. Joel McCrea’s galloping across a windy prairie. Barbara Britton, fresh from Vermont, stands out front of their sodbuster cabin. Why is he so late? Is there trouble? What can I do, a woman alone? I’ve worn out three disks this fall. Almost any Copland (today it’s the Pittsburgh Symphony conducted by some Israeli) can persuade me on almost any given day that I’m not just any old man doing something old men do: driving to the grocery for soy milk, visiting the periodontist, motoring to the airport to greet young soldiers….It doesn’t take much to change my perspective on a given day—or a given moment, or a given anything.

When Frank reaches the beach, he’s stopped by a cop he knows, Corporal Alyss of the Sea-Clift PD. There follows one of those brilliant set pieces that Ford does so well:

Palm forward, Officer Alyss transforms himself now into a human Jersey-barrier, warning off looters, unauthorized rubberneckers, and sneakers-in like me. When I buzz down my window, he comes round to utter his discouraging words, big right hand rested on his big black Glock. He’s much larger than the last time I saw him. Portland concrete seems to have been added to his shape and size, in-uniform. He doesn’t quite move naturally—fully Kevlar’d with heavy, combat footwear as thick as moon boots, plus his waist-harness of black-leather cop gear: scorch-your-eyes perpetrator spray, silver cuffs, a walkie-talkie as big as a textbook, a head-knocking baton in a metal loop, extra ammo clips, a row of black snap-closed compartments that could hold most anything, plus a pair of sinister black gloves. He is the Michelin man of first responders….

Along with the photographic precision of the description, note the almost imperceptible phrase “discouraging words,” which nods to the idyllic western daydream generated earlier by Copland’s music. Similar touches—the repetition of the phrase “I’m here” or the word “bedrock”—subtly unify these ongoing scenes from a retirement.

Even though Frank’s mind runs on old age—“I feel a need to more consciously pick my feet up when I walk—‘the gramps shuffle’ being the unmaskable, final-journey approach signal”—he’s still shocked when he sees Arnie, who “looks like somebody who used to be Arnie Urquhart.” The fishmonger-king has had cosmetic surgery, there’s apparently a new young wife, and he’s

wearing a sharp, brown-leather, thigh-length car coat, high-gloss, low-slung Italian loafers, a pair of cuff-less tweed trousers that probably cost a thousand bucks at Paul Stuart, and a deep maroon cashmere turtleneck that altogether makes him look like a mafia don.

As they talk, Arnie—who is clearly resisting the advent of age as fiercely as he can—displaces his own anxiety onto the former realtor. One quietly snide phrase follows another: “You’re slippin’, Frank.” “You look a little peakèd. You takin’ care of yourself?” “You’re well out of it, Frank.” He even makes fun of Frank’s Sonata.

But gradually Arnie softens, confessing that “it”—life, old age, keeping up appearances, everything—“is rough, Franky.” When they part, he breaks down and embraces his fellow sexagenarian who, to his own surprise, returns the hug. As Arnie stoically declares, “Everything could be worse.” And he’s not just talking about his ruined house. Yes, as Frank murmurs to himself, everything could be “much, much worse than it is.”

“Old age,” said Leon Trotsky, “is the most unexpected of all the things that happen to a man.” Like a story by Chekhov or Eudora Welty, “I’m Here” never overtly addresses its real subject, but its title makes clear what that is. “I’m here,” we learn, was the phrase a group of Sioux Indians shouted out, again and again, just before they were all hanged. The words, Sally tells Frank, “made it all right for them. Made death tolerable and less awful. It gave them strength.”

Advertisement

At the beginning of the second story, “Everything Could Be Worse,” Frank arrives home after his weekly gig reading to the blind on the radio. The program’s current book, Naipaul’s The Enigma of Arrival, is—according to a recent intervew in Le Nouvel Observateur—one of Ford’s own favorites. In it a Naipaul-like narrator, who has moved into a house in rural Wiltshire, reflects on his life, the people around him, his own loneliness, and his efforts “almost from the beginning to make myself ready for this end.” By “end,” he isn’t just thinking about a quiet place in the country.

As Frank pulls into his driveway, he sees a well-dressed black woman on his doorstep. Is she collecting for the AME Sunrise Tabernacle? In fact, Charlotte Pines has stopped by because, years before, she grew up in Frank’s house and would like, if possible, to take a quick look around. Frank is welcoming, though initially awkward in her presence: “Almost all conversations between myself and African Americans devolve into this phony, race-neutral natter about making the world a better place.” Despite himself, he utters one embarrassing, altogether discouraging word after another. When Ms. Pines asks if a certain door still leads to the cellar, he answers that it does, but “it’s full of spooks down there.”

As it happens, though, Frank speaks truer than he knows. Even when his visitor explains that she is the daughter of Hartwick Pines, that information means nothing to him. Frank merely thinks that the name sounds like “a woodwinds camp in the Michigan forests. Or a Nuremberg judge. Or a signatory of Dumbarton Oaks.” So Ms. Pines tells her story.

Just as “I’m Here” addresses how one lives, right now, with physical aging and the shadow of mortality, so “Everything Could Be Worse” looks at how one deals with the lifelong psychological pain of a family tragedy, as well as the extra burden of being black in white America. So, too, the returning vets that Frank greets on the tarmac must live with their traumatic experiences of battle in the Middle East. Though he reaches out to Charlotte Pines, as well as to the wounded warriors, Frank views his well-meaning efforts as feeble and wholly insufficient.

In “The New Normal,” Ford transports us to still another house—the Community at Carnage Hill, where Frank’s ex-wife Ann has moved as she begins to face the onset of her debilitating disease. To most of us, including Frank,

nothing’s bleaker than the stingy, unforgiving one-dimensionality of most of these places; their soul-less vestibules and unbreathable antiseptic fragrances, the dead-eyed attendants and willowy end-of-the-line pre-clusiveness to whatever’s made life be life but that now can be forgotten.

At Carnage Hill, however, even illness and infirmity are given a chic optimistic spin, and long-term care dubbed “a multidisciplinary experience.”

As Frank walks in on the center’s Christmas party, he thinks back over Ann’s life since their divorce, recalls her two subsequent husbands, and tries to avoid her crude roughneck “boyfriend” who is gulping down Malbec and snacks. In fact, he always finds Ann “prettier than I remember her, as if having a progressive, fatal disease agrees with her.” She obviously dresses to the nines for Frank’s visits and boldly decorates her room with Georgia O’Keeffe–like vaginal art. Even the nursing home’s transgendered security guard, a combination of burly strength and little-girl cutesiness, adds to the disturbing sexual charge.

Still, everything about Carnage Hill ultimately feels fake or forced, its spaces resembling the bleak, unlived-in showplaces of Architectural Digest. Little wonder Frank yearns for a glimpse of wildness, of raw life:

I’m still gazing round the over- cogitated room, wishing something would take place: a smoke alarm going off. The phone to ring. The figure of a Yeti striding through the snowy frame of the picture window, pausing to acknowledge us bestilled within, shaking his woolly head in wonder, then continuing into the forest where he’s happiest. There’s not even a Christmas tree here, nor a mirror. Rules restrict such things. Vanities.

On these stress-filled visits, Frank presents his “Default Self,” that is,

the self I’d like others to understand me to be, and at heart believe I am: a man who doesn’t lie (or rarely), who presumes nothing from the past, who takes the high, optimistic road (when available), who doesn’t envision the future, who streamlines his utterances (no embellishments), and in all instances acts nice.

Yet even in the midst of Carnage Hill’s artificial glitz and last-gasp sexuality, there’s no disguising reality: “At some point you just need to leave the theater so the next crowd can see the movie.”

In the first three sections of Let Me Be Frank With You, Ford addresses a devastating present, a tragic past, and a diminishing future. In the last story, “Deaths of Others,” Frank is called to the bedside of the dying Eddie Medley, once “jolly as a jester and handsome as Glenn Ford.” In personality, Eddie used to present himself as “a smiling Thorny Thornberry,” a neighbor

to go to the big game with, or to talk things over late into autumn nights at some roadside bar; a friend who helps you hand-plane the fir boards to the precise right bevel edge for the canoe you hope, next June, to slide together into Lake Naganooki and set out for some walleye fishing.

Thorny Thornberry? No one under sixty remembers this bit player from The Adventures of Ozzie and Harriet. Who now, for that matter, remembers the actor Glenn Ford? While Frank may live in the aftermath of a 2012 hurricane, he isn’t wholly of the twenty-first century. He recalls with admiration his onetime father-in-law, an engineer who built real things back when America actually built things. He chats with Sally while working on his own plumbing repair, “tightening the threaded collar on the sink drain with a pipe wrench four times bigger than I needed but that once belonged to my father and thus was sacred.” Smartphones and fast Internet don’t exist in this world. Frank isn’t even sure what a blog is. His bedrock values are traditional—hard work, sacrifice, family, the golden rule.

At the doorway to Eddie’s house, our hero encounters Fike Birdsong, a repulsively unctuous minister “no more sincere about god than an All-State agent.” Fike is immediately contrasted with “big, pillowy” Finesse, a black hospice nurse in “tight red toreadors with little green Christmas trees printed all over them.” Unlike the phony minister, she truly ministers to the dying Eddie, treats him with tough love, and deserves our respect and thanks. We should all be so lucky when our time comes.

To reach the patient’s bedside, Frank must first pass through an elegant front parlor, then a home theater, followed by a “paneled man-study,” which is succeeded by a club room and an “expensively lit seafaring chamber” filled with maritime charts and nautical gear—every single room needing major repairs and upkeep. Finally, he reaches shrunken, emaciated Eddie, who, like his house, is in rapid decay: “At the end, life does not become him.” Frank notices that two TVs are playing—one showing white men in business suits on the stock exchange,

soundlessly ringing in another day’s choker profits and looking blameless. On the other is an aerial view of The Shore. Surf sudsy. Beaches empty. The famous roller coaster, up to its knees in ocean.

He speculates that “possibly everything to a dying man is an emblem of the same thing: it’s all a lot of shit.”

Eventually, Eddie confesses a past betrayal, begging forgiveness before the pancreatic cancer carries him off. When, at last, Frank exits into the late-morning sunshine, he encounters Ezekiel Lewis delivering heating oil. Like Finesse, Ezekiel

is good on any scale of human goodness. He is thirty-nine, attends the AME Tabernacle over in the black trace, coaches wrestling at the Y, teaches Sunday School, volunteers at the food bank. His wife, Be’ahtrice, teaches high school math and knows the universal sign language. He is bedrock. The best we have to offer.

Outside the dying man’s crumbling mansion, Ezekiel tells Frank that “our church’s taking a panel truck of food and whatever over to those people sufferin’ on The Shore. Cain’t do that much. But I’m here. So I cain’t do nothin’.” Those last three sentences, one of them echoing the first story’s title, summarize Frank’s moral code: “Cain’t do that much. But I’m here. So I cain’t do nothin’.”

Serious fiction, the kind Richard Ford writes, is always, finally, about life and death and how one should live. Let Me Be Frank With You concludes with just “a few good words” spoken by two good men on Christmas Eve. But because of Ezekiel’s unassuming empathy for others, Frank finds that “the day we have briefly shared is saved.”

“For me,” Richard Ford once said,

what we are charged to do as human beings is to make our lives and the lives of others as liveable, as important, as charged as we possibly can. And so what I’d call secular redemption aims to make us, through the agency of affection, intimacy, closeness, complicity, feel like our time spent on earth is not wasted.

In four rambling, digressive, and irresistible stories Let Me Be Frank With You shows us that ideal in action.