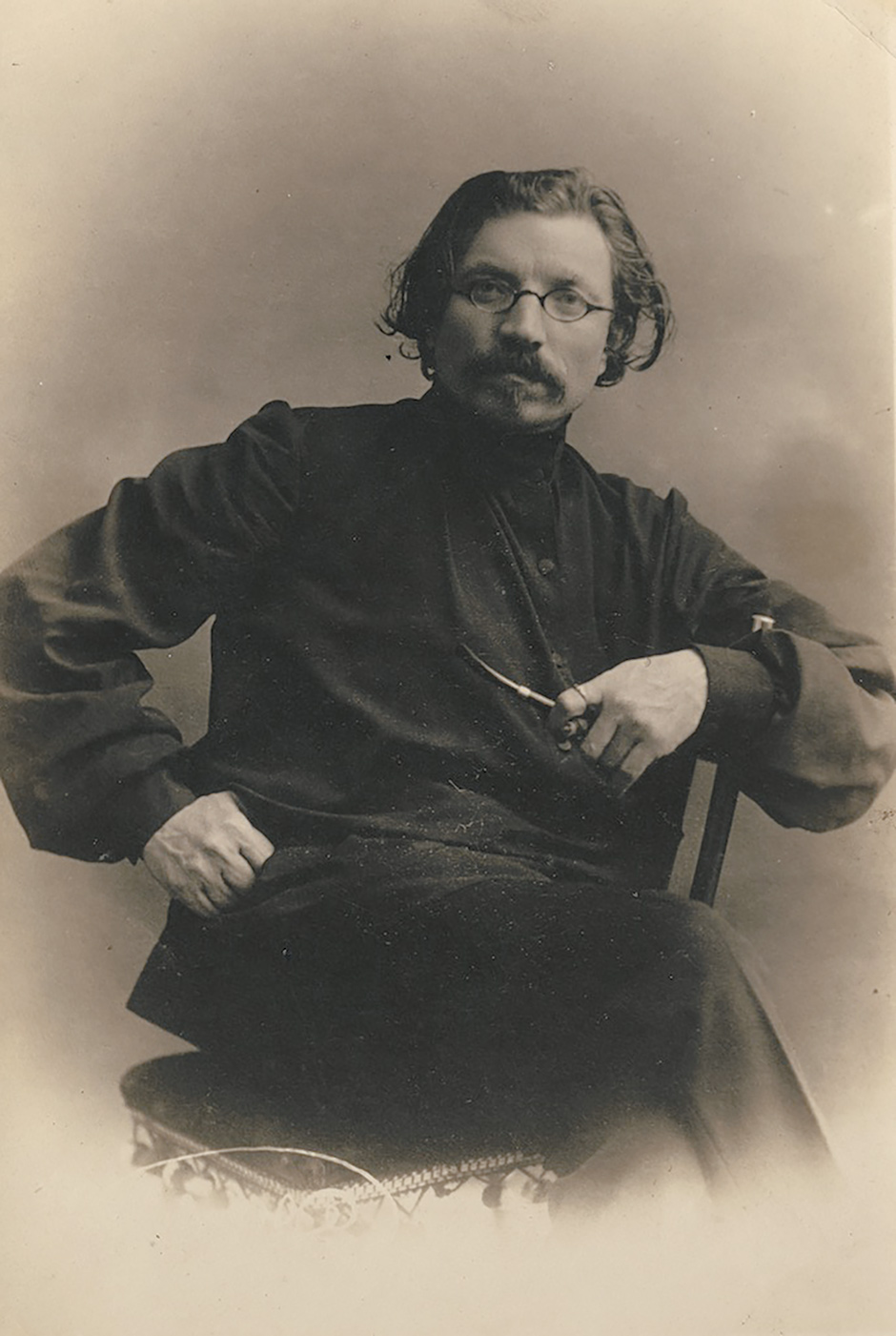

Fiddler on the Roof, which opened fifty years ago and had 3,242 performances, was the longest-running musical in Broadway history. We now have not one but two books about it—Alisa Solomon’s Wonder of Wonders and Barbara Isenberg’s Tradition! We can anticipate numerous revivals in professional theaters, schools, and summer camps. A reading of the Tevye stories by the great Yiddish writer Sholem Aleichem, on which much of the musical is based, was staged last summer at the Martha’s Vineyard Playhouse. Norman Jewison’s Academy Award–nominated 1971 movie version will soon appear at a number of film festivals. There is also Laughing in the Darkness, a film by Joseph Dorman, about the life of Sholem Aleichem, concluding with his funeral attended by 250,000 people in New York City in 1916. And there was last year’s rigorous biographical study by Jeremy Dauber (The Worlds of Sholem Aleichem), the concluding fifty pages of which were totally devoted to the musical the author never wrote.

Of all these, Alisa Solomon’s book is the best written, the most scholarly, and the most painstaking—while at the same time it is the most bewildering. A distinguished former critic for The Village Voice, now teaching arts and culture at Columbia’s School of Journalism, Solomon has done a prodigious amount of research. Her book includes a prefatory study of the life and career of Sholem Aleichem, and a comprehensive account of the entire Fiddler phenomenon, beginning with the first story ever published about Tevye the Milkman in 1894. Indeed, she approaches Fiddler on the Roof by producing a closely reasoned, learned dissertation, consisting of almost four hundred pages, 350 footnotes, and a twelve-page bibliography, devoted to the making and marketing of a Broadway musical hit.

She spends the first tenth of her book on Sholem Aleichem (or Sholem-Aleichem as she prefers to hyphenate his name) and how, fleeing a series of pogroms in the Ukrainian part of Russia, he sailed to America from Europe in 1905 in the hope of reforming the “sensational melodramas” or tasteless shund (“trash” in Yiddish) of Yiddish playwriting. (“I will never permit myself,” he announced, “to give in to American taste and lower the standards of art.”) These reforms he expected to introduce as he launched his own career as a playwright in the Yiddish theater, offering new plays to companies led by Jacob Adler, David Kessler, Boris Thomashefsky, and any local director willing to produce them.

Celebrated as an international literary hero, Sholem Aleichem lectured to overflow crowds throughout the US, and wrote two plays simultaneously produced by two different theater companies. Both were failures (scorned as insufficiently “American” by conservatives and as insufficiently revolutionary by leftists). He returned to Ukraine where he lived with his family until, jolted by another pogrom in Kiev and the outbreak of World War I, he came back to New York in 1914, dying there in 1916 at the age of fifty-seven.

Enlightening as Alisa Solomon is about Sholem Aleichem’s life, she is obviously more eager to explore the creative development of Fiddler on the Roof almost fifty years after the author’s death. She traces the way a musical featuring a milkman from a fictional shtetl named Anatevka was first adapted and produced off-Broadway by Arnold Perl as Tevye and His Daughters, then briefly considered for Broadway by Rodgers and Hammerstein, then by Mike Todd, and finally produced by Joseph Stein (book writer), Sheldon Harnick (lyrics), and Jerry Bock (music).

In the original stories, Tevye actually has not five but seven daughters, one of whom (for obvious reasons not a character in the musical) commits suicide. The creators of Fiddler concentrated on the marriages of only three—Tzeitl, who through Tevye’s ingenuity marries Motl, the tailor she desires (instead of the wealthy old butcher Tevye’s domineering wife Golde prefers); Hodel, who falls in love with a revolutionary and follows him in exile to Siberia; and Chava, who, to the despair of Tevye (he sits shiva for her as if she were dead), chooses as her mate a Gentile intellectual.

Solomon dutifully describes all these marital ordeals, but the drama that engages her most is the rehearsals for the musical. She is particularly diverting when she describes the mischievous attempts of the original star of Fiddler, Zero Mostel, to provoke the director-choreographer Jerome Robbins. By naming names before the House Un-American Activities Committee, Robbins had earned the undying contempt of Mostel, an unrepentant radical. (He once told Arnie Reisman that he was planning a remake of The Informer with Robbins playing the title role.) Mostel never tired of calling the eminent New York City Ballet choreographer (also the celebrated director of works like West Side Story) “that putz.” (“A couple of weddings in Williamsburg,” he muttered, “and that putz thinks he knows orthodox Jews.”)

Advertisement

Robbins (who had the same surname as Sholem Aleichem—Rabinowitz) made his acting debut at the Yiddish Art Theatre in 1937, but had been concealing his Jewishness ever since almost as carefully as he had been hiding his identity as a gay man. And this proclivity for subterfuge turned him into the perfect foil for Mostel—who made much of his ethnic identity, trumpeted his radical politics, and acted out anything on his mind at any given moment. One example was Mostel’s insistence on kissing the mezuzah on Tevye’s doorpost every time he entered the house, over Robbins’s futile protests that it made the show too Jewish.

The travels of Fiddler on the Roof through the months of its conception, its rehearsal period, its troubles on the road, and its wildly successful Broadway opening are the main subjects of Solomon’s book, which is filled with lively character sketches of the various participants. They include, among others, Hal Prince the producer, Boris Aronson the designer, Austin Pendleton, who played Motel, and Bea Arthur as Yente the matchmaker.

Almost all of these notables had run-ins with Robbins, who, while central to the success of the work, is gradually revealed as being among the most intimidating figures in American theater since the bad old days of producer Jed Harris. He abused the cast, drove the designers crazy, strained the good nature of Hal Prince, and managed to make everybody involved in the production feel as if they were soiling his great tapestry.

In a section entitled “Tevye Strikes It Rich,” Solomon spends considerable time on the evolution of Fiddler’s popular score—notably its opening number, “Tradition” (“the dissolution of a way of life”), the waltz elegy “Sunrise, Sunset” (which made audiences cry), and the upwardly mobile fantasy “If I Were a Rich Man” (“All day long I’d biddy biddy bum”). But the most indelible metaphor of the musical, and the visual image used in its poster, namely a violinist fiddling away on the roof of a house of the Anatevka shtetl, is of course borrowed from a famous Marc Chagall painting.1 As Solomon makes clear, Chagall hated Fiddler and refused to have his name associated with it.

On Broadway, with its large audience of assimilated Jews, the success of a show often hinged on the way benefit groups like Hadassah, the Women’s Zionist Organization of America, regarded their changing American identity. The main challenge confronting the creators of Fiddler was that this identity at the time was in considerable flux. Many Jews, like the television host David Susskind (who once described himself as being of “the Hebrew persuasion”), tended to get nervous discussing their origins, preferring to adopt the erect posture of militant “Hebrew” Israelis rather than the Yiddish shrugs of intimidated Eastern Europeans. Even a Jewish work laundered of its Yiddishkeit seemed to people like Susskind too “ethnic” for majority audiences. So it apparently did to Norman Jewison (despite his name, not the son of a Jew). When he made his three-hour film adaptation of the musical in 1971, he replaced Zero Mostel with Chaim Topol, an Israeli star.

This odd sort of Americanizing made some others complain that the show wasn’t ethnic enough. Sholem Aleichem had often been cited as “the Yiddish Mark Twain” (to which Mark Twain graciously replied that he considered himself “the American Sholem Aleichem”). Although also likened to Chekhov—and to Gorky, whom he physically resembled—he never strayed far from his Yiddish roots. The argument was over whether or not Fiddler was yanking those roots out of their native soil.

Take, as one example, the climactic pogrom. In real life, Sholem Aleichem permanently abandoned Europe as a result in part of a vicious libel against an innocent Jewish clerk named Menachem Mendel Beilis, who had been accused of killing a thirteen-year-old Christian boy in order to bake matzos with his blood. In the musical, the pogrom is preceded by friendly warnings from a kindly Russian officer (the same military class usually portrayed by Sholem Aleichem as savage enemies in fur caps), and is largely an extension of the choreography. There were other significant changes as well. The author of the book, Joseph Stein, once boasted that Fiddler had been written without using a single full page of Sholem Aleichem’s text.

Some revivals of the musical, most notably David Leveaux’s in 2004, would later be accused of “de-Jewing” the already de-ethnicized original. Peter Marks in The Washington Post—proposing that Leveaux’s production be renamed Violinist on the Verandah—complained that the British director had emptied the village of “thick, filling borscht and replaced it with a pallid consommé.” Additionally, as Barbara Isenberg tells us in Tradition!, the lyricist Sheldon Harnick was later willing to accommodate a more diverse, multicultural age by rewriting his lyrics to accommodate gentile, African-American, gay, and lesbian performers.

Advertisement

Isenberg’s Tradition!, by the way, which quotes many of the same interviewees tirelessly repeating the same interviews as in Wonder of Wonders, is more detailed than Solomon’s book in tracing the subsequent career of Fiddler on the Roof. It is certainly more focused on the musical qua musical than on its literary sources, which makes her show-biz style seem more appropriate for the occasion than Solomon’s scholarly methodology.

Nevertheless, one of Solomon’s primary objectives is to defend the musical against the many complaints that it softened or sentimentalized its author’s literary intentions. The critic for the Herald Tribune, for example, wrote that the original 1964 production would be charming “if only the people of Anatevka did not pause every now and again to give their regards to Broadway and their remembrances to Herald Square.”

A similar reaction from critics on the fringe seems to have irritated Solomon considerably more. Those of us crabby enough to make negative comments about the musical were, she said, practicing “the scholarly sport of condemning Fiddler for degrading Sholem-Aleichem.” Although she doesn’t mention the influential New Yorker article by Philip Roth, who called the show “shtetl kitsch,” she criticizes Cynthia Ozick and Midge Decter (“trying to snatch Sholem-Aleichem back from the grubby adjustments of showbiz”), a “cranky” essay by Irving Howe, a “sneering” Ruth Wisse, and a “chiding” Robert Brustein, when I complained in my New Republic review that gifted artists were wasting talent and time on a middlebrow spectacle.

Revisiting my review fifty years after the event, I admit I may have been a bit too sniffy. I was especially hard on Zero Mostel for wasting a major talent—recently devoted to Joyce (Ulysses in Nightown) and Ionesco (Rhinoceros)—on such a lightweight entertainment. Mostel had used the same word to describe the script as Sholem Aleichem did to characterize American theater—shund—and took the role only because he needed money to buy his wife a fur coat. It was, in retrospect, ungenerous of me to begrudge audiences their pleasures, or to criticize Mostel’s wider success, since he never really compromised his talents in the show.2

My colleagues and I could argue that our criticism had a constructive intent in our efforts to defend Sholem Aleichem against the watering down of his writing, reflecting what the author himself meant when he said: “I will never permit myself to give in to American taste and lower the standards of art.” Since the speaker was no longer around to defend his work, some of us were offering ourselves as surrogates—and not only for him but for all those whose art was becoming subject to theatrical exploitation, disrespect, or disregard.

Broadway, driven by the profit motive, had never been particularly hospitable to such European artists as Ibsen, Strindberg, Chekhov, Brecht, or Beckett (all of them dismissed by the New York Herald Tribune critic Walter Kerr, who called Waiting for Godot out of touch with “the minds and hearts of the folk out front”). But the commercial theater had once premiered the plays of such serious American dramatists as O’Neill, Odets, Miller, Williams, Albee, and others. Now even these playwrights were struggling to find a producer. The fact is that Broadway was losing its educated audiences. Those able to attend institutions of higher learning were emerging with little sense of literary culture; even students in the humanities were managing to obtain a bachelor’s degree without having read a single work by Shakespeare.3 Thus instead of enjoying original material, educated spectators were attending musical adaptations of An American Tragedy, From Here to Eternity, Jane Eyre, Don Quixote (Man of La Mancha), Cry, the Beloved Country, Les Miserables, Oliver Twist, Pride and Prejudice, Ragtime, A Tale of Two Cities, and the upcoming Doctor Zhivago.4

Fiddler on the Roof was criticized not because it was singular but because it was so representative. Our concern was whether the fullness and depth of the source material was being sufficiently preserved on the stage. Fiddler was an example of a theatrical piece that took considerable liberties with the work on which it was based. It treated Aleichem’s writing not as a collection of stories but as a combination, as Robbins described it, of “opera, play and ballet.” It also helped to entrench a movement toward brightly presented, upbeat, middlebrow entertainment, launched by Rodgers and Hammerstein’s Oklahoma! in 1943.

The growing indifference of educated people to serious poetry, literature, and drama was somewhat contemporaneous with what Solomon and others would call the “golden age” of the “integrated book musical,” a manifestation hailed then and now as “America’s greatest native art form.” This manifestation is now called “musical theater.” Known in the Thirties and Forties as “musical comedy,” it once was pulsing with sophistication, wit, skepticism, and robust energy (consider Rodgers and Hart’s Babes in Arms and Pal Joey or Cole Porter’s Gay Divorce and Panama Hattie). What Rodgers and Hammerstein introduced first with Oklahoma! and later with South Pacific and The Sound of Music transformed musicals into an American version of Viennese operetta—inspirational, affirmative, pastoral, but lacking in sharp observational wit. (Leonard Bernstein’s musicals were significantly more dark and penetrating, and so were Stephen Sondheim’s, being closer to jazz opera.)

The success of Fiddler on the Roof was a historic moment in popular culture, representing the triumph of a kind of sentimental and superficial air of seriousness on the American stage. The issue was not just that Broadway was reducing powerful literature to song and dance. It was also that ventures like the big-budget musical were edging out more demanding kinds of theater because of their greater accessibility and the celebrity and publicity that accompanied them.

Certainly I am not arguing against popular entertainment, only against its increasing stranglehold on the theater, if not the culture as a whole. Starting with the Elizabethans, high- and low-brow expression had lived very compatibly together, as for example in the way Hamlet’s inexorable progress toward death is lightened by the gravedigger’s graveside humor, or Macbeth’s bloody murder of Duncan is brightened by a drunken Porter puzzled by repeated knocks on the gate.

Similarly, on the Broadway stage in the Twenties and Thirties and to a lesser extent to this day, the broad comic genius of such entertainers as Bobby Clark, Bert Lahr, Phil Silvers, Willy Clark, and Milton Berle (later Sid Caesar and Mel Brooks, and currently Billy Crystal) were regarded as having an important place in serious playwriting. These shows had a tough urban edge that made it possible to combine musical appeal with wit and sophistication (so later did Guys and Dolls and A Funny Thing Happened on the Way to the Forum, a Plautine farce produced in 1962 starring Mostel).

The elevation of the musical to the status of an “art form,” however, a status endorsed by scholars like Alisa Solomon, marked a subtle shift in the way culture would henceforth be evaluated. For it helped fortify the growing process of “dumbing down”—overrating work that usually put no particular pressure on an audience’s intellect, imagination, spirit, or sense of fun. It is often said that the state of a country’s art is reflective of its deeper values. Judging by the condition of our culture today, both in the arts and in the wider society, we must ask if those values have any depth at all. It is no doubt unfair to single out Fiddler on the Roof for special blame in this regard. It has its share of attractions and amusements. But in an age characterized by unregulated markets, luxury, and greed, “If I Were a Rich Man” seems an all too appropriate American anthem for our times.

-

1

This Chagall image was even more vivid than Tevye pulling his milk wagon around the stage like a Jewish Mother Courage, a play that Robbins had directed the year before, with Anne Bancroft in the title role. Unlike Fiddler, the production was a flop. ↩

-

2

I have since been responsible myself for adapting two musicals from the stories of Isaac Bashevis Singer, to which we added traditional klezmer music. Where I think those adaptations are more defensible is in their effort to preserve the integrity of the original work. In Singer’s case, we had the living author’s endorsement, and later that of his estate. ↩

-

3

See William Deresiewicz’s newly published Excellent Sheep: The Miseducation of the American Elite and the Way to a Meaningful Life (Free Press, 2014), among such recent laments, and the review in these pages by Christopher Benfey, October 23, 2014. ↩

-

4

Some might add the American Repertory Theater’s transformation of Huckleberry Finn into Big River in 1984. Actually, that musical was a close adaptation of Mark Twain’s novel that went to Broadway under different auspices than ours, with an entirely different producer, cast, and production staff. ↩