The stories selected in Family Furnishings, a fine and timely follow-up to Alice Munro’s winning of the 2013 Nobel Prize, date (it says on the cover) from 1995 to 2014, thus making a sequel to the Selected Stories of 1996, which drew on the previous thirty years of Munro’s writing. But there is one exception to this dating in the new selection, the magnificent story “Home.” “Home” was first published in a collection of Canadian stories in 1974, so it was written when Munro was in her early forties. She then went on working on it for thirty years, revising, correcting, and changing its shape, and it was republished in much-altered form in 2006: so it appears here as a “late” story. That process of revisiting is fundamental to Munro’s methods. She constantly revises her work; she reuses her subject matter with the utmost concentration and attention; and her characters, like her (and often they are like her), compulsively return to their pasts.

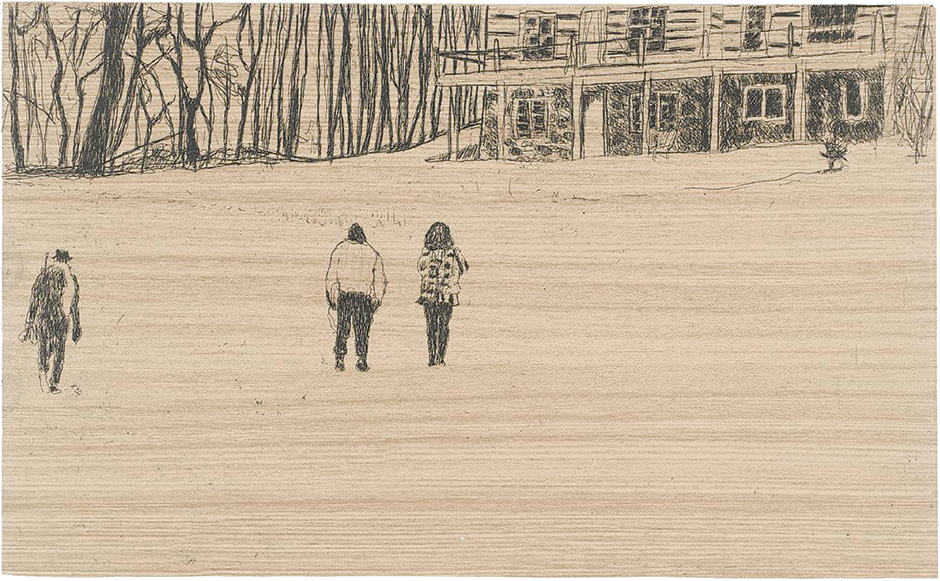

“Home” tells of a visit, in the first person, to the farmhouse she grew up in between the 1930s and the 1950s. All Munro readers know this place, and know that it is a farm in Morris Township, Huron County, Western Ontario, near the town of Wingham, though it often isn’t named in the stories, or is called something else. She is visiting her father and her stepmother, with whom she has an edgy relationship. She is remembering her mother; she is recalling her childhood; she is witnessing, though she doesn’t yet know it, her father’s final illness.

And she is deciding, as Munro’s characters often have to decide, what “home” means, and what to do with it when you have left it:

Time and place can close in on me, it can so easily seem as if I have never got away, that I have stayed here my whole life. As if my life as an adult was some kind of dream that never took hold of me.

Her long journey home begins with three bus rides, the first fast and air-conditioned, traveling along the highway, the second a town bus, the third an old school bus making stops out into the country: as if, stage by stage, she is traveling into a slower close-up of her past life. In the last bus, it is difficult to see out of the windows:

I find this irritating, because the countryside here is what I most want to see—the reddening fall woods and the dry fields of stubble and the cows crowding the barn porches. Such unremarkable scenes, in this part of the country, are what I have always thought would be the last thing I would care to see in my life.

Something very similar happens in a story called “The Beggar Maid,” in Who Do You Think You Are? (1978), anthologized in the earlier Selected Stories, where a scholarship girl at university from a poor rural family has to deal with her rich, clever boyfriend’s snobbery. His condescension to her uneducated family and “unremarkable” surroundings, which she herself at this point can’t wait to get away from, brings her confusion and misery:

Nevertheless her loyalty was starting. Now that she was sure of getting away, a layer of loyalty and protectiveness was hardening around every memory she had, around the store and the town, the flat, somewhat scrubby, unremarkable countryside.

“Loyalty” might seem an odd word to pick out as the key to a writer who famously betrays her home, her family, and her tribe in order to make stories out of them, and who exposes with ruthless energy and a cold eye the shameful secrets of the long-ago past. In the stories, she often reproaches herself for these betrayals—she knows that she has “escaped things by such use”—and is reproached for it by those she has left behind and then made use of.

“Use” is a loaded, uneasy word in Munro: when she goes back to her hometown she sometimes feels that she has “written about it and used it up.” She knows the shifty, blurring lines between “using,” “using up,” and “making use of.” But she is committed to the principle of using everything up, just like her Scottish Presbyterian Laidlaw ancestors, whose immigrant history she reconstructs in one of her most lavishly staged, large-scale, and well-known stories, “The View from Castle Rock.” That “rock” of Puritan principle appeared at once, when she first started drawing on her family life. In “The Peace of Utrecht” (1960), a young woman returning to her family home after her mother’s death visits her aunts, who, to her horror, have saved her mother’s clothes for her, which she rejects:

They stared back at me with grave accusing Protestant faces, for I had run up against the simple unprepossessing materialism which was the rock of their lives. Things must be used; everything must be used up, saved and mended and made into something else and used again.

Wanting to shed the family stuff, yet needing to use it and make it “into something else”: the theme is echoed in the title phrase of this new selection. It’s spoken by a character called Alfrida, a cousin of the narrator’s father, once an object of fascination to the girl, now a burdensome reminder of the past. Alfrida’s house is stuffed full of furniture. “‘I know I’ve got far too much stuff in here,’ she said. ‘But it’s my parents’ stuff. It’s family furnishings, and I couldn’t let them go.’” The Munro-ish girl in the story, busily trying to shed her “family furnishings” as fast as she can, will also find, by the time she becomes the writer of this story, that she “couldn’t let them go.”

Advertisement

In spite of herself, the writer has remained loyal. She is loyal to place and the past, faithfully and perpetually reconstructing it, so that no one, having read her, would ever again say, “What’s so interesting about small-town rural Canada?” She is loyal to truth, getting the detail precisely right in every phrase and word, so that people, habits, objects, scenes, and places that are lost and gone in the real world remain alive on her pages. (“It was more than concern she felt, it was horror, to think of the way things could be lost….”) She is loyal, also, to her chosen form, masterfully working and reworking it all her life, so that no one in the world now would say, “Why didn’t Alice Munro ever write a novel?” or “Why would a short-story writer win the Nobel Prize for Literature?”

Writers who get away from, or are in savage dispute with, “home,” yet spend most of their lives writing about it, are not uncommon, especially in North America: think of Shillington, Pennsylvania; Newark, New Jersey; Milledgeville, Georgia; Jackson, Mississippi; Red Cloud, Nebraska; or Great Village, Nova Scotia. What is special about Munro’s lifelong use and reuse of “family furnishings” and “unremarkable” local landscape?

Partly it is her exceptionally thorough and dedicated mining of the same ingredients, which endlessly come up rich and fresh, seem never to be used up, and however artfully shaped, feel “real.” Lives of Girls and Women (1971) was going to be called Real Life. Munro’s “real life” ingredients become enormously familiar to us: the childhood in the fox farm on the edge of town, the mother with incurable Parkinson’s, the studious girl reading her way out of the country into university, the expectations for young women in 1940s and 1950s provincial, conservative, colonial Canada; the early marriage and motherhood in Vancouver, the condescending young husband, the adultery, the divorce, the deaths of her parents, the returns home.

In her stories about her mother’s past, “My Mother’s Dream” and “Dear Life,” she nudges us to remember that this is “real life,” even though she didn’t witness it herself: “It is early morning when this happens in the real world. The world of July 1945.” “He does not have any further part in what I’m writing now…because this is not a story, only life.” But Munro has also issued warnings about reading any of her work as “not a story, only life,” as in her introduction to The Moons of Jupiter (1982): “Some of these stories are closer to my own life than others are, but not one of them is as close as people seem to think.”

Just when we are tempted to treat everything she writes as autobiography, she will make her central character into the abused wife of a child murderer (“Dimensions”), or a nineteenth-century Russian woman mathematician (“Too Much Happiness”), or a teacher in love with a doctor in a TB sanatorium (“Amundsen”). So we have to be wary of calling all these stories “only life.” But that doesn’t make them feel any less real. How is it done? It’s often hard to work it out. Jane Smiley, in her affectionate, admiring introduction to this volume, is happy to throw up her hands, call it magic, and leave it at that.

Part of the magic comes from the stories’ fabulous naturalism. While Munro’s characters are going about their business, not much noticing the scenery (except for the Hardyesque woodsman in “Wood”), she is noticing it for them. The late stories have a special tenderness for landscapes, especially at their most indeterminate:

Mist was rising so that you could hardly see the river. You had to fix your eyes, concentrate, and then a spot of water would show through, quiet as water in a pot.

And such a long time it takes for today to be over. For the long reach of sunlight and stretched shadows to give out and the monumental heat to stir a little, opening sweet cool cracks. Then all of a sudden the stars are out in clusters and the trees are enlarging themselves like clouds, shaking down peace.

Meanwhile everyday jobs are being done (Munro is as good at this as Updike is): bread-making, shoe repairs, milking a cow, drying fox pelts, cleaning a foundry floor. We learn what we need about “working for a living” (the title of one of the stories), about odd corners of houses, about how families eat their meals. The lives of objects sing out from these historical stories, which shrewdly and knowingly, often satirically, take us through a century or more of closely observed regional life.

Advertisement

But naturalism and historical accuracy are only the half of it. Munro is famous for her destabilizing treatment of time, jumping us far ahead, or back to something we’ve missed. She is wonderfully crafty at making her stories seem to move both forward and backward, to be at once anticipatory and elegiac. A girl sits at the kitchen table, doing her Latin translation, chewing her pencil, and writing: “You must not ask, it is forbidden for us to know—what fate has in store for me, or for you.” Munro’s characters, like us, don’t know what fate has in store either, but she often lets us look ahead and find out.

The slow-burning fuse that is a Munro story frequently hides, then exposes, something violent, shameful, or sensational. Down-and-out characters struggling on the edges, psychopathic killers, vindictive children or vengeful old people, abused women, passionately self-abnegating lovers, irresponsible adulterers, horrible acts of cruelty, startlingly show up inside these domestic, realistic narratives. “Southern Ontario Gothic,” this gets called, though the luridness of “Gothic” doesn’t quite fit the remarkable mixture of savage extremes and formal control.

The mixture is at full blast in the first story in the selection, “The Love of a Good Woman” (1996), which follows one of Munro’s favorite structures, or plots, the slow uncovering of a secret act of violence, emerging from an environment where there is too much surveillance, too much unspoken knowledge, too many collaborations in silence, too much shame. In this story, the corpse of a small-town optometrist is found in his car in an icy river by a gang of boys, and the secret story of his murder is revealed, as unpleasantly as possible, to the nurse of a malevolent dying woman. The vindictiveness of the characters in this story can take your breath away:

Once a woman had asked Enid to bring her a willow platter from the cupboard and Enid had thought that she wanted the comfort of looking at this one pretty possession for the last time. But it turned out that she wanted to use her last, surprising strength to smash it against the bedpost.

“Now I know my sister’s never going to get her hands on that,” she said.

And there’s the heart of the magic: the voice of the speakers, and the voice of the narrator who has them speak. From the start, Munro has been brilliant at this, but in the late stories she has developed an extraordinary elastic fluency, a way of moving without any apparent effort between vividly distinctive local voices, and the sense of someone talking to themselves, or repeating a tale, and something more resonant and contemplative. So we hear, very exactly, as if in our ear, the voice of flattening, down-putting comment, the voice of know-all neighbors, the voice of score-settlers:

You want to know what Alfrida said about you?… She said you were smart, but you weren’t ever quite as smart as you thought you were…. She said you were kind of a cold fish. That’s her talking, not me. I haven’t got anything against you.

In the simplest of words, and with the greatest of power, she makes us see and hear an “unremarkable” scene we will never forget:

Across from my father is the bed of another old man, who has been removed from it and placed in a wheelchair. He has cropped white hair, still thick, and the big head and frail body of a sickly child. He wears a short hospital gown and sits in the wheelchair with his legs apart, revealing a nest of dry brown nuts. There is a tray across the front of his chair, like the tray on a child’s high chair. He has been given a washcloth to play with. He rolls up the washcloth and pounds it three times with his fist. Then he unrolls it and rolls it up again, carefully, and pounds it again. He always pounds it three times, one at each end and once in the middle. The procedure continues and the timing does not vary.

“Dave Ellers,” my father says in a low voice.

“You know him?”

“Oh sure. Old railroad man.”

The old railroad man gives us a quick look, without breaking his routine. “Ha,” he says, warningly.

My father says, apparently without irony, “He’s gone away downhill.”

We are not going to be allowed to look away from “real life.” Nor is the narrator going to let herself off the hook, about what can be forgiven, what must be regretted, what needs to be told. In some of the most moving stories, we hear the narrative voice asking questions of herself, returning to her own life as to an unresolved problem. In “Soon,” the daughter, as usual, revisits the family home while the father is looking after the increasingly frail and demented mother. The daughter holds the mother at bay; if she doesn’t, she feels she will be sucked in, will never get out or get back to her own life. The mother, Sara, says to the daughter, Juliet, in a shaky voice that at the time seems to the daughter “strategically pathetic”: “When it gets really bad for me—when it gets so bad I—you know what I think then? I think, all right. I think—Soon. Soon I’ll see Juliet.”

But the daughter does not reply, and will look back on this moment, later, with desolating self-reproach. Writing it as though she is talking to herself out loud, Munro folds the unbearable emotion, with great beauty, tact, and sorrow, into the everyday:

When Sara had said, soon I’ll see Juliet, Juliet had found no reply. Could it not have been managed? Why should it have been so difficult? Just to say Yes. To Sara it would have meant so much—to herself, surely, so little. But she had turned away, she had carried the tray to the kitchen, and there she washed and dried the cups and also the glass that had held grape soda. She had put everything away.