“Don’t be cross with me that I’ve come all of a sudden,” Vincent van Gogh wrote to his brother. He instructed Theo to meet him under the Mona Lisa at the Louvre. It was late February 1886. Vincent was about to turn thirty-three. He arrived in Paris to complete an artistic education that had so far yielded no financial returns for his long-suffering sibling paymaster; nor did Vincent’s career promise the slightest profit in future. Now Theo, a dealer at the art gallery Goupil & Cie, was expected to put him up.

As Julian Bell reminds us in a splendid new biography, Vincent had dabbled as a self-appointed preacher in the grimy coalfields and pit villages of the Belgian Borinage. He had mostly taught himself art on the margins of Antwerp, Brussels, and The Hague. Now he was just catching up with the Impressionists in Paris when the movement was nearly exhausted.

Mostly unimpressed, van Gogh saw the future of modernism in figures like Adolphe Monticelli, a mediocrity in multiple genres whose work he came across at a gallery run by a friend of Theo’s. Along with Seurat and Signac, Hiroshige and Hokusai, Monet and Toulouse-Lautrec, Monticelli would help point Vincent away from potato eaters and gray, wintry landscapes toward sunshine and the south. It turned out that Vincent’s obstinacy and sheer otherness, much as they pained friends and family and alienated strangers, bought him the perspective he needed to reach this juncture, where he could pick and choose his sources and stake out a path for himself.

He was, in his daily routine, no less self-destructive than he had been before, drinking, smoking up a storm, making himself ill; and he had still not yet shed the evangelical side of his early art, beating up old shoes he bought at a Paris flea market so that he could paint yet more metaphors of poverty and struggle. Still, Paris became a chrysalis.

Bell has written what he describes, rightly, as an “unmystified” and compassionate biography. It follows the encyclopedic biography by Steven Naifeh and Gregory White Smith, published in 2011, a painstaking, brilliant, almost ceaselessly downbeat account of the life that nonetheless left room for a compact, personal take like this one, by a painter-writer about a painter-writer. Bell’s sympathy for his subject abides; his prose is angelic. He outlines the life without melodrama and with just enough exasperation at Vincent’s loutish, morose, and egocentric shenanigans. The book really comes alive when Bell describes specific pictures and their mechanics. Paintings by Lautrec, he writes, are

woven together out of fine strands of color scribbled, dabbed or hatched onto a warm neutral ground—with an end result in which the weave stayed naked to the eye, so that complementary pairings such as oranges and blues electrically vibrated.

This sort of description can bring to mind how van Gogh talked about his own work. To Émile Bernard, for instance, he wrote near the end of his life about a canvas he painted at the asylum in St.-Rémy, The Garden of Saint-Paul Hospital. “You’ll understand,” he told Bernard,

that this combination of red ochre, of green saddened with grey, of black lines that define the outlines, this gives rise a little to the feeling of anxiety from which some of my companions in misfortune often suffer.

Countless freeloaders, lost teenagers, parents of lost teenagers, and disappointed artists have found consolation in Vincent’s misfortune. His story is the ultimate “I told you so”: a troubled, not obviously talented oddball, who through determination and sheer chutzpah is finally, albeit mostly posthumously, recognized as a genius. Van Gogh is today the most popular artist in the world for the stupendous works he made during the last troubled years of his life—a great secular saint of modernism, whose suffering and sacrifice produced pictures of such idiosyncrasy and luminosity that even Kirk Douglas and obscene sales records and Starry Night shower curtains have done nothing to trivialize the ravishment of seeing the art in the flesh. That his mental instability fueled leaps of creative imagination has only made him seem more noble, in the Romantic vein—albeit, as Bell cautions, “insofar as Van Gogh the painter communicates to us, with an oeuvre that viewers for over a century have found uniquely thrilling and sustaining, it is not our business to call him mad.”

Fair enough. He was bipolar, maybe; or epileptic. The medical jury is still out. But it doesn’t matter. The art, which does, is the opposite of insane: lucid like Vincent’s letters, one of the great epistolary legacies of the nineteenth century, despite their unreliability as biographical evidence. As Patrick Grant puts it in a recent critical study, the letters stoop to “special pleading, evasion, manipulation, and the like,” yet still make vivid the courage and cunning Vincent brought to his “imperfect” life and art.*

Advertisement

As a child he was stocky, inward-turning, with hunched shoulders and furrowed brow. He loved to read but was miserable at boarding school, with few friends, quitting at the age of fourteen and returning to the family parsonage, where he stormed out of the house at all hours to wander the heath in the rain. Naturally, his parents despaired. He was too awkward and morose to follow in the footsteps of his father Dorus, a humble, small-town Protestant minister. Instead, he was apprenticed to a branch of Goupil, where his uncle Cent, a suave and worldly art dealer, was a partner. Vincent became a junior assistant in The Hague, packing prints, reading Romantic poetry in his spare time, gaining his first first-hand knowledge of serious art.

After a while, Goupil sent him to deal with trade customers in London, realizing that he didn’t make, as Bell nicely puts it, “front-of-house material.” His work brought him into daily contact with prints by socially conscious artists like Daumier and Doré. And for a while, he seemed to brighten. He became more outgoing, until his landlady’s daughter rejected his advances and then he spiraled back downward. Goupil shifted him to Paris, where rather than immersing himself in the latest art trends, he threw himself into religion, becoming contemptuous of the business side of art, slovenly and impertinent in his job. Enough was enough. Goupil fired him. At twenty-three, Vincent was unemployed and directionless.

So for a while he kicked around, teaching school, working in a bookshop, finally determining to become a priest before realizing, predictably, that he lacked the focus and patience to pass the exams. In 1879 he set off as a self-appointed missionary to the coal miners in Belgium, where he tended to the unfortunate with tireless but alarming piety, staying up long nights to nurse victims of a mine explosion, sleeping on a straw bed because he had ripped up the bed linens his parents sent to him to make bandages, wallowing in his righteous squalor, weeping at night. When he got back home, his father tried to have him declared insane.

Earnest, good-hearted Dorus was a rector in the Dutch Reformed Church, “a short, slight man who mumbled and rambled,” Bell notes, but an authority figure to his parishioners, standing up for Protestantism in what was a Catholic backwater of the Netherlands, bordering Belgium. He preached social responsibility. Vincent battled with him but clearly learned from Dorus’s proud and independent example. Theo was the son temperamentally most like Dorus among Vincent’s five siblings: sensible, sensitive, a “middleman, good and modest like his father,” as Bell puts it. He was the one who encouraged Vincent to pursue art when everything else had failed.

Vincent had been drawing since he was a boy. Art teachers at school had instructed him in some of the basics. He began to take himself seriously in the Borinage. Models found him weird and pushy. His subjects—laborers and vagrants, prostitutes, orphans, peasants and housemaids, hard at work—were drawn with compassion but without skill at conveying their particularity and weight. They were symbols, types. A drawing like Miners in the Snow is a typically uncertain field of scratches and stick figures. Even so, the seeds of something special were being sown.

“Real artists paint things not as they are, in a dry analytical way, but as they feel them,” he told a fellow artist.

I adore Michelangelo’s figures, though the legs are too long and the hips and backsides too large. What I most want to do is to make of these incorrectnesses, deviations, remodelings, or adjustments of reality something that may be “untrue” but is at the same time more true than literal truth.

It was of course by then orthodox for artists to be unorthodox, emulating Delacroix and Daumier, Manet and Monet, not Couture and Cabanel, but for Vincent, “failing” by academic standards also justified his own fundamental differentness.

Translating that differentness into an original art was obviously the challenge. He apprenticed to Anton Mauve, who lent Vincent some technical command; he paid a carpenter to build him a mechanical window grid, mounted on a tripod, so he could make more accurate drawings of the industrial wastelands, factories, and fields he admired, to match his glum figure studies. He fell in with George Hendrick Breitner, a painter of street scenes and gritty, Zola-like naturalism, who took van Gogh to soup kitchens and construction sites, from which came drawings like Torn-Up Street with Diggers, from April 1882, a collage of working-class characters, disposed willy-nilly with not much thought to perspective. And in Brussels, Vincent attached himself to Anthon Ridder van Rappard, another young painter, affluent, amiable, steady, unlike him. Rappard would recall van Gogh as “violent” and “fanatical.” But for a while they worked side by side.

Advertisement

Vincent might be called a drama queen today. Bell recounts the story of when his widowed cousin Kee turned him down in love. Van Gogh held his hand over an oil lamp and threatened to burn himself. (His uncle calmly blew out the flame.) He endlessly cajoled and guilt-tripped Theo into forking over cash. Bell doesn’t quite stress enough just how cavalier Vincent was with Theo’s money; he felt he was owed support. “It seems to me that it is much less a matter of earning than of deserving,” he told Theo. Naifeh and Smith call it what it was, a “delusional sense of entitlement.”

But by 1884, when he is back home, now caring for his bedridden mother, his drawings have in fact become rather remarkable. A voice has emerged. Bell notes “a suite of large and exquisitely delicate pen drawings, done in March 1884,” that “surpass” in their poetic eloquence the works of John Everett Millais, a Pre-Raphaelite van Gogh admired. I assume he is referring to solitary figures in winter fields and other landscapes, like the one of a tortured stand of pollard birches—the trees like “a procession of almshouse men,” as Vincent described them. Its spiky aura leaps off the page. You can see in these drawings a distinct vocabulary of cursive script: electrified, blanketing patterns of lines, akin to metal filings pulled by some invisible force across sheets of paper.

Vincent noted it himself: “My power has ripened,” he wrote. As proof of his intent to make good on his career, he sent to Theo The Potato Eaters with its sacramental, earthen scrum of peasants, like a grove of gnarled tree trunks around a pine table, the work that Vincent would value above all others to the end. Of course it was unsellable; at the same time its awkwardness was virtuosic.

Then in Paris, van Gogh’s encounters with Ukiyo-e, Lautrec, and Signac lift him once and for all “from the murk,” in Bell’s phrase. By 1887, Vincent abandoned heavy impasto and reveled in an expressive range of dots and dashes, lattice lines, and basket-weave patterns. His years of etching helped: printmaking had taught him how to suggest movement through the directions of stippled lines. It all comes together by the autumn of 1887 in canvases like Quinces, Lemons, Pears and Grapes, a “single resounding chord of yellow,” Bell declares, with “an all-over crackle of visual electricity through the emphatic, polyrhythmic hatching that was his and his alone.” The paintings no longer aimed toward instruction but delight. Color made people happy. Vincent wanted to spread pleasure. That was still God’s work.

Bell’s telling of van Gogh’s last, miraculous, disastrous years is humane and eloquent. From Paris, Vincent went in 1888 to Arles, “more foreign to a Parisian than Tunis is today,” as the art critic Robert Hughes once put it. Provence was ablaze with colors van Gogh had not seen. Awestruck, he wrote to Theo about a landscape of

green-gold, yellow-gold, pink-gold …all the way to a dull, dark yellow color like a heap of threshed corn. And this combined with the blue—from the deepest royal blue of the water to the blue of the forget-me-nots, cobalt.

The colors liberated van Gogh’s imagination. His brushwork of dashes and coils now expanded to match the wild forms he discovered in nature. From Bernard, he occasionally borrowed a Cloisonné organization of shapes into patterns like stained glass. The mismatched colors around the billiard table at the local bar, buzzing under yellow lights, expressed his new reality. Arles was a place of excess.

That his fantasy about establishing a commune with Gauguin ended with the slicing off of an earlobe was a consequence of that excess but belies the evidence of the art, which is profoundly rational. Art provided stability. Bell writes about some copies van Gogh made of Millet prints in the asylum to which he admitted himself at St.-Rémy:

Twist, hook, curl, stroke, pat, pat, pat went the brush, first probing then docile, the knot of the preordained image resolving itself into a balm that soothed…. The olive groves…now spoke to him with their low, regimented tree boles and their mounds of raw red earth as a comfortable pictorial terra firma—one that carried just sufficient connotations of the garden of Gethsemane to remind him of his love for Jesus…. And then by contrast there was the walled garden over to the monastery’s west side…perseverance and repetition took on a heroic demeanor.

At St.-Rémy and Auvers, Vincent found yet a newer pitch in painting halftones and the enclosure of the asylum. Gone are the entitlement and self-pitying:

I am not strictly speaking mad, for my mind is absolutely normal in the intervals, and even more so than before. But during the attacks it is terrible—and then I lose consciousness of everything. But that spurs me on to work and to seriousness, as a miner who is always in danger makes haste in what he does.

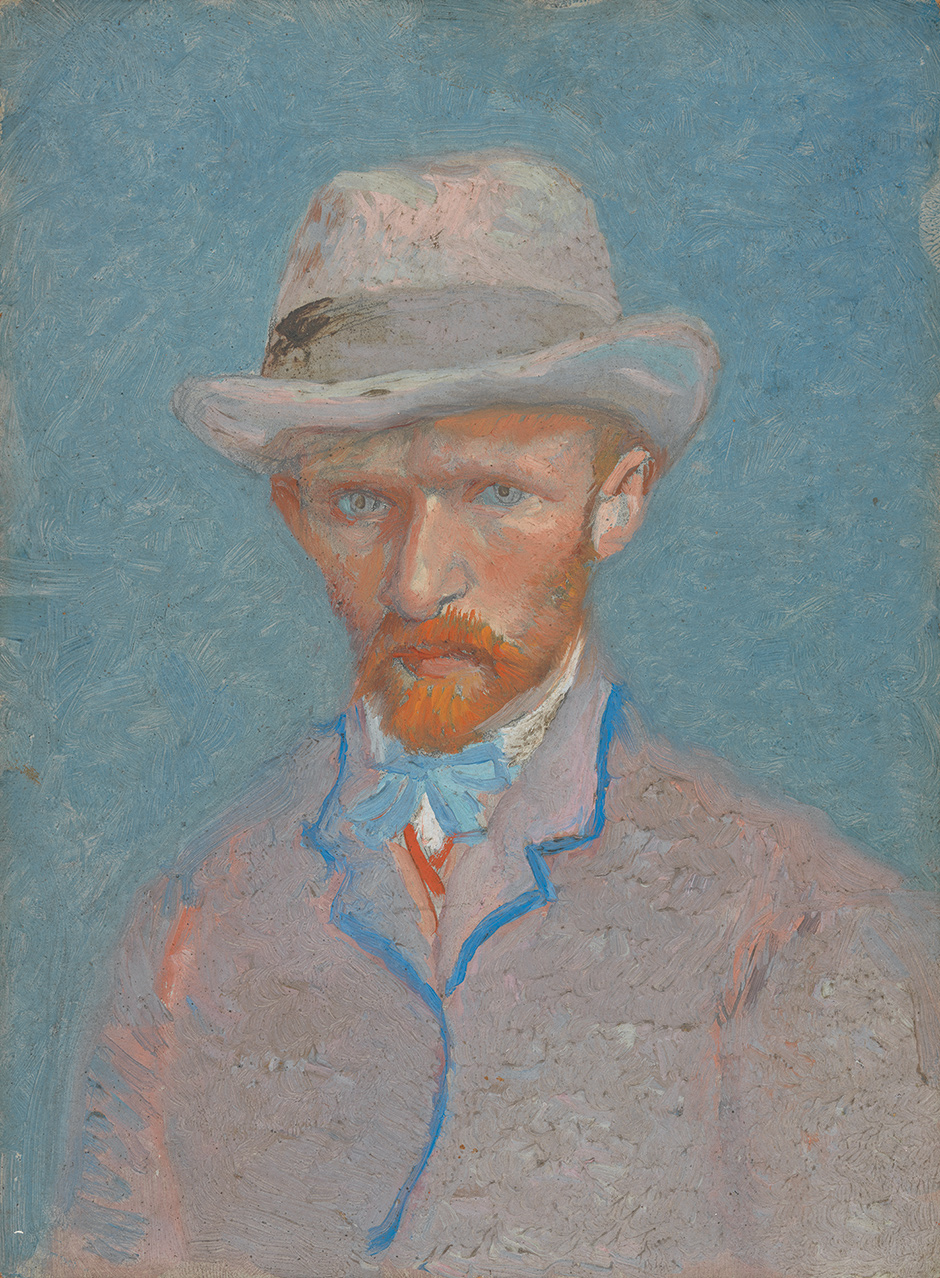

The work is heartbreakingly beautiful. What looks like fantasy in some of the late pictures matched a landscape whose rocky terrain of limestone hills was fantastic. Vincent insisted that he was more committed than ever to “modern reality,” meaning to the wonder of trees and stars and wind and soil. His late portraits beat with the blood of real people; they’re not ham-fisted symbols but animated, sympathetic, alive. Those roiling, curlicue clouds in The Starry Night become vibrating, all-over patterns of lines in a self-portrait where the artist’s face is engulfed by a force field of raw energy. You have to “risk vertigo a little,” he wrote to Theo.

In January 1890, an essay in Mercure de France by Albert Aurier, a young critic and friend of Bernard’s, hails Vincent as a “great painter,” a “sower of truth” who will “regenerate our decrepit art.” Paris wakes up to Theo’s brother. The praise pleases but rattles Vincent. He finds solace painting wheat fields, the “most frantically fluent canvases of his life,” Bell calls them. “I’m wholly in a mood of almost too much calm,” Vincent assured his brother in mid-July.

Bell doesn’t subscribe to Naifeh and Smith’s theory, based on an old rumor, that the fatal shot was fired by local teenagers, accidentally. Vincent’s friend Dr. Gachet—whose incompetence Naifeh and Smith claim was partly to blame for the death, since a good surgeon might have saved van Gogh—drafted a letter to Theo saying Vincent had “wounded himself.” The gun never turned up. The bullet was poorly aimed for suicide, if it were fired by him—“a bad shot,” Bell writes. “In effect, it killed his brother,” he adds. After watching Vincent expire, Theo died not many months later, at thirty-three, of a broken heart and tertiary syphilis.

Vincent was thirty-seven. The abbot in Auvers refused to allow a funeral service in his church. Van Gogh was foreign and Protestant and a suicide.

So Theo bought a plot in a new cemetery on a barren plateau above the town, a distance from the church. Vincent was in his element, among the wheat fields, under the sun and stars, an outlier, as always.

This Issue

February 5, 2015

On Edgar Allan Poe

‘A Beautiful, Mournful Novel’

-

*

Patrick Grant, The Letters of Vincent van Gogh: A Critical Study (Athabasca University Press, 2014). ↩