The photographer Duane Michals is a law unto himself. In a career spanning more than half a century he has worked in both utilitarian black-and-white and luxuriant color, produced slapstick self-portraits, evoked erotic daydreams, pamphleteered against art world fashions, and painted whimsical abstract designs on vintage photographs. You would be in for a disappointment if you expected a sober summing up in “Storyteller: The Photographs of Duane Michals,” the big retrospective of the eighty-two-year-old artist’s career that is currently at the Carnegie Museum of Art in Pittsburgh. Michals remains aggressively idiosyncratic, the curator of his own overstuffed, beguiling, disorderly imagination.

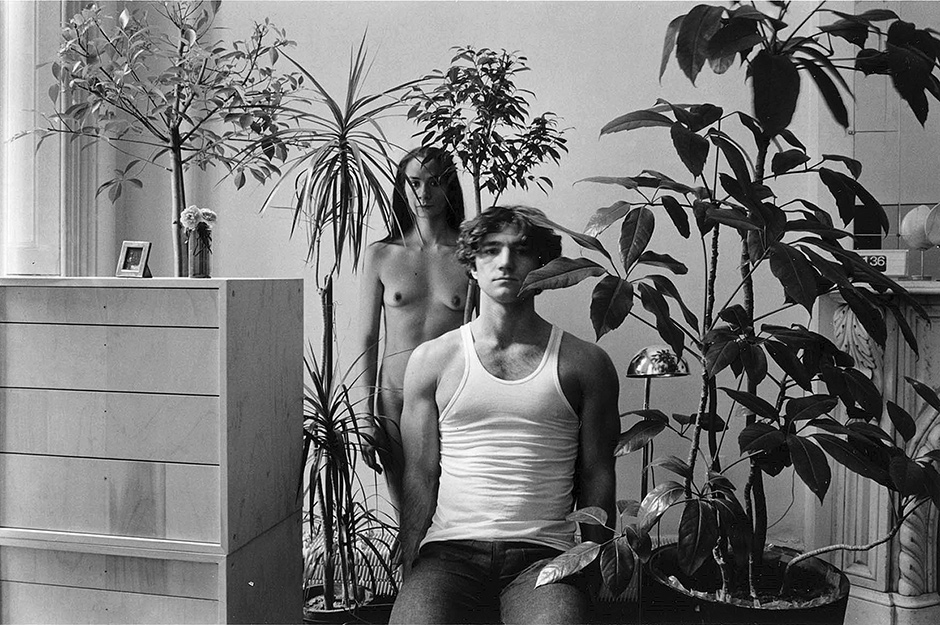

Michals’s reputation was pretty much made in the late 1960s, with sequences of small, black-and-white images that amount to freshly minted fairy tales for adults. These surreal visual fables were shown at the Museum of Modern Art in 1970, when the museum was the arbiter of all things photographic. In the six frames of Paradise Regained, a young man and woman in a modern apartment go back to nature, shedding all their clothes as the houseplants around them grow larger and larger, becoming an Edenic garden. In Death Comes to the Old Lady, presented in five parts, a woman in a housedress is visited by a man in a dark suit before she evaporates in a photographic blur. With such cosmic-comic sequences, Michals became photography’s genial troublemaker, seen by some as thumbing his nose at the lyric realism of Henri Cartier-Bresson’s “decisive moment” and Alfred Stieglitz’s perfect prints. What can all too easily be underestimated is the quick, agile intelligence that Michals brought to his troublemaking. That’s what has given his dissident spirit its staying power.

There is something of Jean Cocteau’s jack-of-all-trades wit, ingenuity, and romantic rapture about Michals and his career. When he wrote, in 1994, that “dreams are the midnight movies of the mind,” it could have been a remark made by the Cocteau of The Blood of a Poet or Beauty and the Beast. Both men combine a reverence for high art traditions with a taste for the quick, teasing powers of popular culture. When a handsome young man appears in one of Cocteau’s films or Michals’s photographic fictions, you can feel the artist introducing him with an impresario’s flourish. Their best work has some of the attention-grabbing power of a practiced raconteur or a virtuoso performer. They seduce us. And their seductions can at times become annoyances (Cocteau was famously annoying). And then they are perfectly capable of seducing us all over again.

Although the galleries of Pittsburgh’s venerable Carnegie Museum are scaled much too large to provide the proper setting for Michals’s intimate art, the show exudes big-hearted goodwill, representing as it does something of a homecoming for Michals, who was born and raised in McKeesport, part of the Pittsburgh metropolitan area. Michals certainly insists on his own story, seeing in his trajectory from working-class beginnings to Manhattan aesthete some clue to the crazy-quilt vitality of his work. A decade ago he published a book, The House I Once Called Home, about the now-abandoned building in McKeesport where he grew up, which becomes in his photographs what he refers to as “the cabinet where my family’s curiosities are stored.” Over the years he has photographed much in and around Pittsburgh, bringing a keen eye to the city’s substantial architectural monuments, strikingly engineered bridges and factories, and dramatic mountains and meandering rivers.

In ABCDuane, a book of autobiographical vignettes organized as an alphabet and published in time for the Pittsburgh show, Michals observes of his friendship with Andy Warhol, a Pittsburgh native, that “we had so much in common, coming from a similar background. We were both blue-collar kids, with a Slovak immigrant heritage and artistic inclinations.” Pittsburgh when Michals was coming of age in the 1940s was one of those tough, prosperous industrial cities where cultural life was seen as an essential element, something needed to balance and sanctify the rest. As a boy Michals took art classes at the Carnegie, where the Carnegie International had long been one of the United States’ premier art exhibitions, attracting both Matisse and Bonnard to serve as jurors. You can still feel, in the octogenarian Michals’s enthusiasm for the achievements of great painters and poets, the bliss that a boy whose father was a steelworker must have felt as he discovered the enchanted atmosphere of a great museum.

Admiration is essential to Michals’s enterprise (this was true of Cocteau as well). In a gallery adjacent to the Michals retrospective, the Carnegie is exhibiting a group of small works by Magritte, De Chirico, Balthus, Braque, Morandi, and other artists that are from Michals’s own collection and that he is donating to the museum. Over the years he has managed to visit and photograph a number of older artists whom he admires and clearly regards as inspirations, masters of the unexpected and enigmatic.

Advertisement

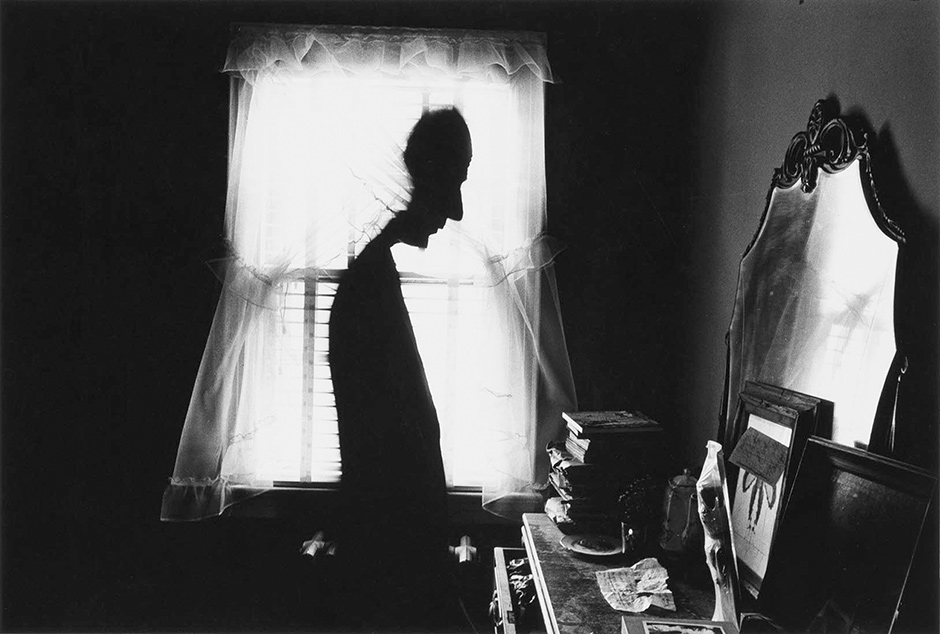

Photography is by its very nature an act of homage, granting unreliable appearances the promise of permanence, but the trickster in Michals cannot resist turning the tables on his subjects by submitting their familiar physiognomies to his sly send-ups of their most characteristic pictorial strategies. In a series of studies of Magritte the artist becomes one of his own paintings, rendered translucent or presented in fragmentary form. Cornell is photographed in a darkened room, the light coming through a window turning his body into a spectral silhouette, as unreal as one of his fantastical French hotels.

These portraits from early in Michals’s career reveal the sassy competitive spirit that energizes his admirations. The photographer is ambushing his subjects. In ABCDuane he observes of his visit to Cornell that he hoped “to become the sorcerer’s apprentice,” but it might be more accurate to say that he aimed to be the sorcerer’s sorcerer. In some of his work Michals reimagines an artist’s or a writer’s imaginings in his own photographic terms, thus giving a paradoxical, parallel reality to the original act of creation. When Michals selects a handsome young man to play the role of Watteau’s Gilles or Chardin’s youth building a house of cards, he creates an associational house of mirrors, the homage both scrupulous and easygoing enough to confound dutiful imitation. And when he stages a first meeting between Gertrude Stein and Alice B. Toklas, with the legendary ladies played by a couple of mustached boys, we enjoy watching as he attempts to top Stein’s already over-the-top self-mythologizing.

For Michals, who has razzed the photographic purists by writing titles and extended captions directly on his prints, the narrative tug of the photographically illustrated book may prove the ideal artistic setting. Over the years he has lavished considerable energy on such projects, his photographs sometimes reproduced in rich, deep-toned gravure. His extended homages to poets he admires—Salute, Walt Whitman (1996) and The Adventures of Constantine Cavafy (2007)—are both storybooks and scrapbooks, a series of free improvisations on themes and images from the work of the two authors. These books give Michals room to expand, shifting the mood at will, mingling erotic fantasies with amusingly scattershot historical reconstructions and elements of downright slapstick, especially in the Cavafy volume. In ABCDuane there is a section titled “Burlesque,” and one feels that the make-believe of burlesque, which can be simultaneously tacky and unforgettable, reveals much about Michals’s art.

In Salute, Walt Whitman—some images are included in the Carnegie show—a well-built, blond young man plays the multitude that Whitman adored. Michals intersperses passages from Leaves of Grass, Specimen Days, and the memories of Whitman’s beloved friend Peter Doyle with images of the blond youth clambering out of a lake onto a rock, relaxing in a wheat field, and holding a candle and a bouquet of flowers. In some photographs the young fellow wears jeans or a Speedo-style bathing suit, while in others he puts on a Union uniform and impersonates a Civil War soldier. Occasionally he meets up with an older, bearded man who plays Walt Whitman, and toward the end the two of them are brought together in a contemporary eatery, actors now at ease, their coffee in paper cups.

Michals lingers on the young man’s terrific physique and innocent, handsome face, all the while reminding us that he is only playing a role and that Michals is the magician who’s pulling the strings. In an especially sharp sequence the young man looks very closely at a little frog he’s holding in his hand, and the profiles of man and frog are elegantly juxtaposed for a new variation on beauty and the beast, the frog in its own way a kind of beauty.

Michals’s contradictions are all wonderfully on display in The Adventures of Constantine Cavafy, in which the photographer’s friend the actor Joel Grey (who in recent years has pursued a second career as a photographer) plays the Alexandrian poet in skits loosely based on Cavafy’s poems. For all his feeling for Cavafy’s exquisite melancholy, Michals cannot resist giving the poet’s career some moments of almost Charlie Chaplin hilarity. Grey brings to the photographic sequences a practiced performer’s sophisticated body language and changeable, expressive face. He provides a welcome vitalizing foil to the succession of imperturbably handsome young men, Cavafy’s love objects, encountered in cafés, in rented rooms, and on the street.

In one sequence Grey and Michals—identified as Konstantinos Kavaphes and Dimitris Michaleides—sit down together, two old friends. Grey, playing Cavafy, watches two guys arm wrestle; he receives an unexpected kiss from a hunk in a T-shirt emblazoned with the name of McKeesport, Michals’s hometown; and he steals wistful glances as a dreamboat lounging in a café reads a book of Cavafy’s own poems. In an epilogue—The Poet Decorates His Muse with Verse—Grey covers the bare chest of a youth sitting up in bed with sheets of paper inscribed with his own poems. This image—funny and absurdly romantic—says much about Duane Michals.

Advertisement

Michals’s work, with its handwritten captions and ad hoc theatrical skits, has a homespun informality. This is what prevents some of his more highfalutin meditations on time, love, death, and immortality from tumbling into portentousness. In a statement posted at the entrance to the Carnegie show, he adopts the role of the streetwise Platonist, explaining that the appearances that photographs capture must not be confused with reality. “I am a reflection photographing other reflections within a reflection,” he writes. “To photograph reality is to photograph NOTHING.” If we are inclined to accept that mouthful, it’s because Michals offers it with a wink. He invites us to enjoy photography’s dime-store magic and Victorian roots when he photographs the soul leaving the body, whether as a grandmotherly photographic blur, or a grandfather disappearing in a flash of light, or a translucent naked man departing from his solid naked self. The most basic darkroom tricks are wedded to basic questions of life and death. We are allowed not only into the darkroom but also into Michals’s own doubts, equivocations, and second thoughts, which can have a winningly sweet-and-sour savor.

Metamorphosis, grounded in the camera’s illusionistic powers, is the essential impulse in Michals’s work. He creates the illusion of time travel, when Walt Whitman and his young friend hang out in what is self-evidently a modern coffee shop. He turns anyone he wants into a Christ figure by granting him a photographic halo. He uses photography to spin what amount to Ovidian legends, as in The Bewitched Bee, a sequence of thirteen images in which a young man stung by a bee grows antlers, wanders through the woods, and finally drowns in a sea of leaves. He uses photography to revitalize the gingerbread nightmares of old children’s stories, as in Margaret Finds a Box, in which a little girl disappears into a corrugated cardboard box that then levitates and vanishes, leaving behind only an inscrutable cat. Time and again, Michals argues that since photography always has a fundamentally ambiguous relationship with reality, we might as well go right ahead and tweak appearances.

His fascination with transformation and metamorphosis is not surprising. After all, he has himself undergone a metamorphosis, born in a working-class Pennsylvania family and ending up a celebrated artist, his work exhibited around the world. As a man who has moved from one class to another without ever losing his feeling for the world he knew as a child, Michals is naturally drawn to an art of masks and unmaskings and multiple illusions and realities. Like some of the artists he most admires—I’m thinking here of Cornell and of Saul Steinberg, whom he has also photographed—Michals is equally enchanted by the art of the museums and the popular spectacle of the streets. He revels in the heterogeneous visual culture of the country that Ralph Ellison once characterized in writing about the work of his friend Romare Bearden as “a collage of a nation.” Like Cornell and Steinberg, Michals refuses either to use popular culture to attack high culture or high culture to attack popular culture.

Michals’s class consciousness, if one cares to call it that, is humorous and benign. His message is that many different things can be classy. His imagination is pluralistic. What he rejects, both in ABCDuane and in Foto Follies: How Photography Lost Its Virginity on the Way to the Bank, his 2006 jeremiad against the contemporary art world, is artists who depend on too narrow and programmatic a view of influence and inspiration. He confesses his skepticism about Pop Art, which he first encountered when he photographed some of the artists for a magazine assignment in the early 1960s, referring to their work as “popcorn,” some of it “art-school desperate,” “a novelty item.” In Foto Follies he announces, contra his Pittsburgh sympathies: “Art is never boring. Andy Warhol was boring.” What offends him in much of the new photographic or photo-based work—by Cindy Sherman, Andreas Gursky, Jeff Wall, Richard Prince, and others—is its self-importance, the sense of the artist as armored in a stylistic gesture or an ideological stand. He refers to one of Gursky’s enormous photographs as “a billboard with pretensions,” and speaks of an era of “foto fast food.”

Some will see his attacks on the new generation of photographic stars as nothing but the resentment of an older generation for a younger generation’s success. Michals, who is surely aware of those criticisms, must also be aware that the new pop-infused photographic ironies can at least in part be seen as building on his own impurities and impieties. The only work by Cindy Sherman that in my view makes a serious claim on our attention—the early Untitled Film Stills, small black-and-white images with Sherman disguised as a gallery of women out of TV and B movies—may owe something to Michals’s early photographic sequences.

And yet Michals has savagely parodied Sherman, donning a sort of platinum wig and prancing around as “Sidney Sherman.” In accompanying texts he mocks the theoretical pretensions that surround Sherman’s work, writing of “dis-corroborative gender bias” and “a phallic ploy of alpha males vis-à-vis Derrida’s strategies of dis-corroboration.” What Michals misses in Sherman is some saving simplicity, a feeling for the fundamental, untheorized, and untheorizable self. “Diane Arbus is authentic,” he writes. “Cindy Sherman is inauthentic.” It enrages Michals to see human emotions giving way to icy poses.

Whatever you may think of Michals’s criticism of the photographic stars of today—I find much of it convincing if slapdash—he brings you back to his own never-ending celebration of self-deprecatory lightness and mischievous fun. This is not to say that Michals always proves the steadiest critical guide to his own achievement. Although I like Foto Follies as a rabblerousing pamphlet, I think it was a mistake to include some of the Sherman parodies in the Carnegie show. In his desire to launch another zinger, Michals can end up with a flat-footed one-liner. Then again, his stunts can be a way of pushing his work into fresh, unexpected territory. Working in color a few years ago, he produced a series of photographs in the shape of fans, their off-center compositions echoing the stylized naturalism of Japanese prints. A quartet of photographic fans records his country garden in the four seasons; a fan emblazoned with groupings of roses in vases is a salute to his mother’s taste in flowers. These photographs dare to be dismissed as kitsch, and yet the kitsch cannot be entirely untangled from the heartfelt, hedonistic opulence of the color.

For a recent New York show, at the DC Moore Gallery in 2013, Michals painted abstract designs on antique tintype portraits. He has always been something of a frustrated painter, but in the past I think he has struck out when painting an apple or a pear in blazing color on his black-and-white photographs. In this new series of slightly altered or metamorphosized tintypes, some included in the Pittsburgh retrospective, Michals limits the brushwork to a few witty, abbreviated additions to the late-nineteenth- or early-twentieth-century images—a couple of Cubistic lines here, several Art Deco flourishes there. A portrait of an older gentleman, on which Michals has inscribed a cagelike mask of zigzagging lines, becomes James Joyce.

The most striking in the group, Guermantes Way, is of a handsome, bright-eyed, nattily dressed young man, whom Michals has ornamented with just a few quivering lines and circles that echo the Cubist still-life etching by Braque in Michals’s own collection. These painted tintypes, with their something-old-something-new juxtapositions, seem to take as their subject the transformation of a nineteenth-century imagination into a modern imagination. They are fragile conceits, but like some of Saul Steinberg’s visual jokes, Michals’s painted tintypes have remarkable staying power.

Michals’s entire career has been a succession of conceits, feints, and games. Push too hard on his work, expect too much of it, and you may find his gallant, gutsy, puckish energy evaporating, much as the human souls in his photographic sequences vanish into thin air. You might imagine that a Michals retrospective as big as the one at the Carnegie Museum would fail to sustain a museumgoer’s attention, and yet this is not the case, which proves that there is some hidden strength in his unfolding caravan, with its burlesques, sideshows, and sundry amusements. No wonder Duane Michals has always felt a particular affinity for the image of the house of cards. His work is a perpetual balancing act.