For over thirty years Charles Baxter has been not only a remarkably good writer, but a professional teacher of writing. To understand what this really means, let us assume that he has maintained a very modest schedule, giving only two fiction workshops a year, with an average of ten students, each of whom has turned in five stories or their equivalent as part of a novel. At a minimum, therefore, Baxter has now read about three thousand stories, most of which, we have to assume, were not remarkably good. He will also, most probably, have kept up with what has been published during these thirty years, reading or rereading at least one story every week, for an additional 1,560 stories.

It is not surprising, therefore, that after a while Baxter became overfamiliar with and critical of the tools that fill the workboxes of most writers of fiction. The result was an intelligent, occasionally impatient, and very enjoyable book, Burning Down the House (1997), in which he shows how well these devices have worked for other gifted writers, past and present, but questions their continued use.

In a chapter called “Against Epiphanies,” for instance, Baxter discusses what a student I used to know called “stupid little realization stories.” Once upon a time, he says, as in Joyce’s “Araby,” the sudden rush of knowledge and/or self-knowledge was new, surprising, and effective. Now, however, “Everyone is having insights…. Everywhere there is a glut of epiphanies…. But…there is a smell about them of recently molded plastic.” One problem is that these insights tend to “depend on an assumption that the surface is false.” There is also often an implication that characters in a story who do not have these insights are morally or intellectually inferior. “Now that the production of epiphanies has become a business, the unenlightened are treated with sad pity, and with the little grace notes of contempt.”

Another thing that troubles Baxter is that so few stories today have protagonists who make important decisions and act on them. He believes that it is the duty of writers to “nudge but not force [their characters] toward situations where they will get into interesting trouble, where they will make interesting mistakes that they may take responsibility for.” Too often today “the story is trying to find a source of meaning, but…everyone is disclaiming responsibility. Things have just happened.”

Baxter questions the social assumptions that underlie much contemporary fiction. In the past, writers like Zola or Dreiser often assumed that the political system was at fault; today we still “believe that people are often helpless, but we don’t blame the corporations anymore. We blame the family.” Today, he remarks, many protagonists suffer harm in childhood and spend the rest of their lives feeling miserable because of it. All they can do is identify the source of the harm, which “is a life fate, like a character disorder.”

Confronted with this mode,…I want to say: The Bosses are happy when you feel helpless. They’re pleased when you think the source of your trouble is your family…. They even like addicts, as long as they’re mostly out of sight. After all, addiction is just the last stage of consumerism.

Blaming an unhappy past often excuses whatever characters do later, and this sort of attitude, Baxter claims, is fatal not only in fiction but in life. “When you say, ‘Mistakes were made,’ you deprive an action of its poetry, and you sound like a weasel. When you say, ‘I fucked up,’ the action retains its meaning.”

Baxter also complains that too many contemporary stories lack real antagonists, whether human or corporate:

Stories…from which the antagonist has disappeared are grounded…in drift and privacy and a sort of aesthetic sadism. Stories in which desire meets resistance in private are often about hysteria, which is melodrama that has come in through the back door.

He remarks that on TV we often see people who admit to having hurt others. “Usually, however, there’s no remorse or shame. Some other factor caused it: bad genes, alcoholism, drugs…. So we have the spectacle of utterly perplexed villains deprived of their villainy.”

Like many writers who have become impatient with current literary conventions, Baxter has experimented with other possibilities. In his short novel The Soul Thief (2008), for instance, he plays with point of view and narrative voice. Though written in his usual straightforward and attractive natural style, the book is a dizzying construction of concentric circles. The inner one, which takes up most of the space, appears at first to be the first-person history of a not especially brilliant but decent and serious graduate student in Buffalo, New York, called Nathaniel Mason. “In his private faith are several articles: Life is a gift and is holy. Love is sacred. Existence is simple in its demands: We must serve others with loving-kindness. Some entity beyond our knowledge is out there.”

Advertisement

Nathaniel Mason’s antagonist, Jerome Coolberg, is the Soul Thief of the book’s title. He is a Dostoevskian character disguised as another much less likable graduate student. Feeling himself to be empty and without an individual personality or self, he proceeds, with considerable success, to take over Mason’s identity: stealing his name and clothes and furniture, sleeping with the two women Mason loves and doing his best to destroy both of them.

All this causes Mason to have a kind of nervous breakdown, but he recovers, leaves Buffalo, and moves on. Twenty years or so later, when he is a modest and moderately successful California college professor, with an affectionate wife and two great kids, he meets Jerome Coolberg again in Los Angeles. There he discovers that Coolberg has continued to track his every move, not only on the Internet but with the help of detectives. Coolberg then gives Mason a manuscript that turns out to be the story we have just been reading and that he, Coolberg, has composed. In other words, the villain has written the hero’s life story.

But of course there is another circle outside of this one: the book written by Charles Baxter, who speaks to us in a final chapter, anticipating the reader’s irritation (“You will say, this is a trick”), and claiming that both he and his narrator “played by the rules.” This is ingenious, but also disingenuous. In the real world a good novel like The Soul Thief is a virtuous act, but identity theft is a crime. Baxter proposes that this crime should be at least partly excused because the larcenous Coolberg (“Iceberg”), through long identification with the virtuous Mason (“Builder”), has become a better person. He is less spiteful and more generous, and therefore, it is implied, no longer deserves to be rejected or condemned. Not every reader will agree with this, or accept Baxter’s conclusion: “The point is that although love may die, what is said on its behalf cannot be consumed by the passage of time, and forgiveness is everything.”

Since Burning Down the House, Baxter has continued to comment on the creation of fiction. In 2007 he published a remarkable short guidebook for writers, The Art of Subtext, which deals with half-concealed messages in literature: what isn’t quite heard, said, or done, but is the central truth of a situation or a life. The creation of such a subtext, he says, is difficult but often absolutely necessary. For Baxter, it seems to be especially important for writers who come from a background like his own, in which the expression of strong emotions is banned:

If you were raised in the genteel tradition, as I was, you avoid scenes…. We create a scene when we forcibly illustrate our need to be visible to others, often in the service of a wish or a demand…. Genteel people fear scenes.

We…were not supposed to be dramatic. Drama was for others, or for the purposes of entertainment. Along with being told not to create scenes, I was told not to tattle on people, which was worded as, “Charlie, don’t tell tales.”

“It is interesting to me now how the construction of a narrative—any narrative—was frowned upon in that household,” Baxter remarks. This sentence, of course, is in itself a striking example of the strategy it describes: the suppressed emotion leaks out around the edges, so that the word “interesting” could more reasonably be replaced with one like “horrible” or “painful.” In the same ironic manner, Baxter points out that being forbidden to tell tales or create scenes “is not the best preparation in the world for writing stories.” This could be translated as “My family made self-expression seem like a vulgar crime.”

In spite of his difficult start, over the past thirty years Charles Baxter has managed to produce a great deal of first-rate fiction, sometimes breaking and at other times visibly struggling against the rules of polite discourse. His best-known novel, The Feast of Love (2000), which was widely praised and made into a film in 2007, is set in what is clearly Ann Arbor, Michigan, and centers on a group of people whose lives are more or less closely linked. They are presented as speaking in the first person to a writer called Charlie who also lives there, as Baxter did at the time.

Though most of these people are clearly reluctant to tell tales or create scenes, after some initial hesitance they tell Charlie absolutely everything about themselves, with emphasis on their romantic and sexual lives, which are full of secrets and lies, deep affection, painful jealousy, overwhelming passion, and occasional violence. Not all of the characters in The Feast of Love come from the genteel middle class; they range from a twenty-year-old punk waitress who almost becomes a porn star to the lonely manager of a mall coffee shop and an aging professor of philosophy with a mentally disturbed son. All of them speak in convincing individual voices, and by the end of the book we feel sympathy even for those we would least want to know personally.

Advertisement

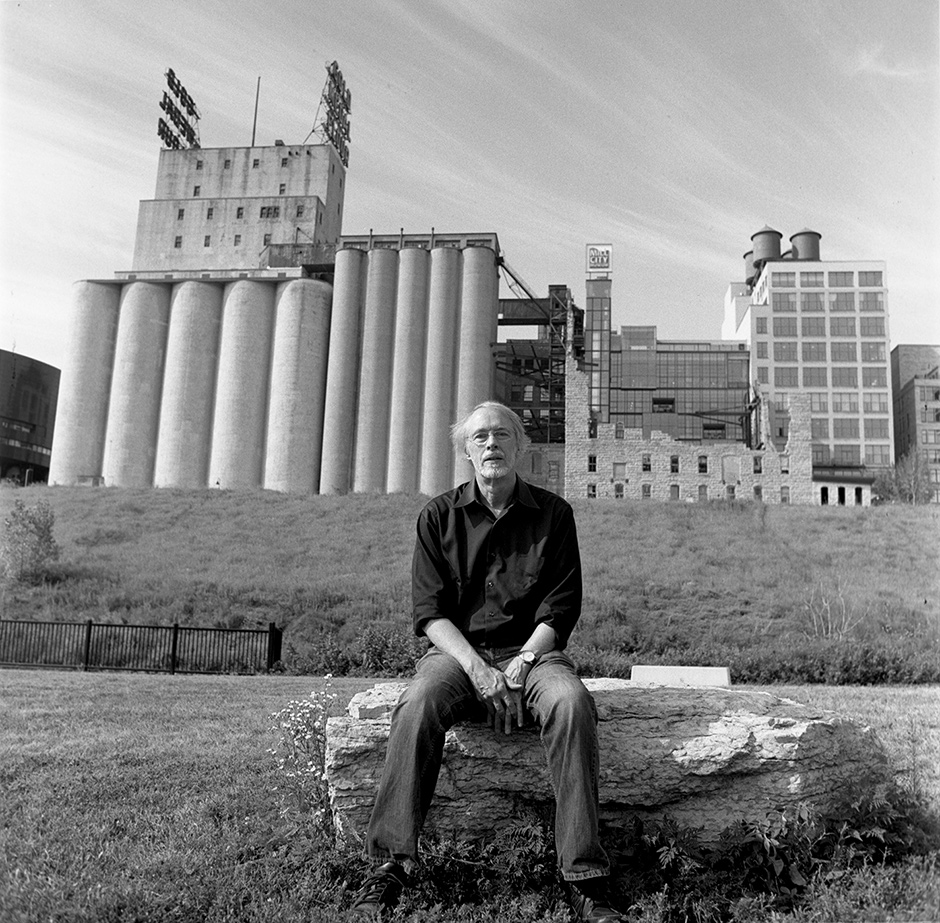

Charles Baxter’s fine new book, There’s Something I Want You to Do, also features a group of loosely connected characters, most of whom live in or pass through Minneapolis, where he currently teaches. It contains ten short stories, the first five named after good qualities (“Bravery,” “Loyalty,” etc.) and the second five after undesirable ones (“Lust,” “Sloth,” etc.), though the characters in the first half of the book are not morally superior to those in the second half. In all the stories someone makes an important request—and, sometimes unexpectedly, these requests are always met.

The world of There’s Something I Want You to Do, like that of The Feast of Love, is one in which diverse characters lead lives of outward conventionality and occasional quiet desperation. Though Minneapolis is not generally considered a romantic location, it has inspired Baxter. He praises its parks and its weather, and in what he calls a “Coda” to the book he speaks of the Stone Arch Bridge across the upper Mississippi, built for train traffic more than a hundred years ago but now limited to people and bicycles:

On warm days in late spring or summer, the bridge serves as a kind of promenade, or gallery, for pedestrians…. These people are gathered here like the Sunday strollers in Seurat’s painting A Sunday Afternoon on the Island of La Grande Jatte, where the beautiful laziness…offers itself as a glimpse of Paradise.

Many of the longer stories in There’s Something I Want You to Do, like those of Alice Munro, read like brilliantly condensed novels. Often they range over many years in their characters’ lives and provide a close look at their worlds. Baxter is also like Munro in the way he treats all levels of society as of equal interest and value. For him the personal history and internal psychological and moral life of a hospital nurse are just as important and complex as that of a highly educated lawyer or doctor.

In this book only two of Baxter’s central characters speak in the first person. Since as readers we unconsciously assume that anyone who talks to us at length, revealing intimate details of their lives, must be a close friend, these two come across as the most dramatically present. One, Wesley, the hero of “Loyalty,” is an auto mechanic, now on his second marriage. He tells us that his first wife, Corinne, complained continually:

The topics were, I don’t know, the usual. I drank too much on weekends,…my hands were always dirty from the shop—and the killer accusation: I was inattentive to her needs, whatever they were. Mostly Corinne complained about herself, her rickety soiled unrecognizable life, her confusion, her panic over our baby,…her sadness, that stuff.

Seventeen years ago, Corinne left town, abandoning Wesley and their baby Jeremy. Wesley married again; his second wife, Astrid, is easygoing and capable. He and Corinne have kept in touch occasionally:

Corinne called Jeremy when he was grown enough to talk, but she couldn’t manage to see him…. She was too delicate…. Visits would put stress on her immune system.

Now she has suddenly turned up in the Minneapolis bus station, and Wesley goes to meet her:

Corinne is already sitting there, waiting on a bench. She has two brown paper bags with her. Soiled clothes are peeking out of the tops of the bags….

Imagine a beautiful woman of middle age who has somehow gone through a car wash. She has dried out, but the car wash has rumpled her up, left the hair going every which way, and on her face is a dazed expression…. Life has worried and picked at her…. My first wife has become a bag lady, and here she is.

“There’s something I want you to do,” Corinne tells Wesley, but she won’t say what it is. She doesn’t need to, really, since her first words to him were “Wes. I knew you’d save me,” and it’s clear that what she wants is to be taken in and taken care of. Wesley obliges, though his wife Astrid is none too pleased and his son Jeremy is furious. “I have to really hate her for a few days,” Jeremy says. “I know she’s crazy. I get that. But I have to hate her for not being loyal to us.”

Here, as in many of Baxter’s stories, there is a subtext. Though Wesley tells us several times that he loves Astrid, it becomes gradually clear that her strength is less attractive to him than Corinne’s weakness. He admits that Corinne was a problem from the start:

Mousy brown hair, mystified by most conversations, unable to fix a dinner you could serve to guests, she was about the most lovable thing you ever saw. I lost my heart to her helplessness time and again.

Now, seventeen years later, he confesses that “she’s still beautiful to me.”

As for Astrid, Wesley praises her skills as a mother and wife, but tells us that “she has…guile.” He relates how, after Corinne left him, Astrid gradually moved in:

In about the time it takes to change the painted background in a photographer’s studio from a woodland scene to a brick wall, she had left her boyfriend and was presenting me with casseroles.

The metaphor reveals the real truth: for Wesley, Corinne was a woodland scene; Astrid is a brick wall.

The other first-person narrator in There’s Something I Want You to Do is Wesley’s mother Dolores. In spite of her name, she is a relatively cheerful, even-tempered old lady who takes up very little space in the world. In one of the book’s most moving and original stories, “Avarice,” Dolores tells us how, many years ago, her husband was killed by a hit-and-run driver: “A rich drunk socialite, a former beauty queen…. After she hit Mike,…she ran over him, both the car’s front and rear tires.” Thinking about it later, Dolores concludes that this woman couldn’t take responsibility for her actions because she would lose too much:

The blue Mercedes, and the big house in the suburbs,…and the swimming pool in back…. All the money in the bank, boiling with possibility, she’d lose all that…. How she must have loved her things, as we all do. God has a name for this love: avarice.

Fortunately, someone has seen the accident and taken down the license plate number, and eventually the former beauty queen goes to prison. But before that Dolores has obsessively planned to kill her. “I dreamed of murder like a teenager dreaming of love.”

Even now, at my age, with knees that hurt from arthritis and a memory that sometimes fails me, I still think certain people should be wiped off the face of the Earth…. All my life, I worked as a librarian in the uptown branch. A librarian with the heart of a murderer! No one guessed.

Eventually, though, “Jesus intervened with me. He came to me one night and said,…‘Dolores, what good would it do if you murdered that foolish woman? It would do you and the world no good at all.’”

Dolores, like many of Baxter’s characters, is seriously religious. She describes Corinne as “bipolar and a middle-aged ruin…. My son, Wesley, her ex-husband, had to take her in. We all did. However, the more honest explanation for her arrival is that Jesus sent her to me.” Though Dolores has not told anyone, she knows that she is dying of cancer, and believes that Corinne will help her through this:

I have it all planned out. I will say to her, “There’s something I want you to do. I want you to accompany me on this journey as far as you can….” She’ll agree to this.

Another recurrent character in There’s Something I Want You to Do is Benny Takemitsu, whom we first meet as a third-generation Japanese architecture student. Benny is another good, kind, reasonable man who tends to ignore the famous advice given by Nelson Algren in A Walk on the Wild Side (1956): “Never sleep with a woman whose troubles are worse than your own.” Instead, like Wesley and many other male protagonists in Charles Baxter’s fiction, he falls in love with very beautiful, spacy, self-centered women. In “Lust,” his girlfriend Nan, a tall, black-haired glamour-puss, leaves him for a sexy triathlete called Thor. To justify this betrayal, she shows Benny a photo of Thor. “She displayed her phone full-frontally with the screen facing Benny…. ‘There he is. That’s him…. Really, can you blame me?’” Benny is devastated, but he does not try to change Nan’s mind. “A man does not beg to be taken back,” he thinks.“Begging qualifies as the primary criterion for admission to loserdom.”

In the fine story “Chastity,” which takes place several years later, Benny has become a successful architect. Out for a walk one night, he prevents a depressed but spectacular-looking young woman called Sarah from jumping off a bridge, takes her home, and eventually manages to marry her, though she does not love him. The something Sarah wants is that Benny should agree never to kiss her on the lips. One possible subtext here is that Benny is responsible for his own misery; that he should have gone ahead and kissed Sarah in spite of her prohibition, and thus won her love. Maybe he misunderstood her; as he thinks at one point, “Irony was the new form of chastity and was everywhere these days. You never knew whether people meant what they said or whether it was all a goof.”

Over the years, several of Baxter’s stories have taken place in what he calls “that critical twilight zone, that landscape haunted by the unseen.” Dolores in “Avarice” not only thinks that Jesus speaks to her, she appears to have second sight. Baxter’s imagination extends into the creation of consciousness not only in the living and the dead, but in objects. In “Gluttony,” Benny’s friend Eli, a pediatrician who is given to overeating, remarks that “the food carried some responsibility for his excesses. It had desires, especially the desire to be consumed.” When he goes for a walk at night, in the story “Sloth,” Eli meets the ghost of Alfred Hitchcock, who is doomed to haunt Minneapolis because it was the hometown of Tippi Hedren. “I must stay here on this bench of desolation until my penitence and contrition are complete,” the director tells him. “I must apologize to the Girl, the one at whom I threw all those birds.”

Baxter follows his recommendation in Burning Down the House that stories should contain an antagonist as well as a protagonist. Now, however, not all of these antagonists deserve our sympathy; the moral of The Soul Thief, that “forgiveness is everything,” no longer holds. In “Forbearance,” for instance, Baxter shows no leniency for the real estate tycoon that the heroine’s brother works for. He is described as

a feral-looking man barely over five feet tall, whose customary expression…was one of superpredatory avarice that mingled from time to time with his one other singular expression, massive sleepy indifference whenever matters of common human experience, those that were not for sale, were exposed to him.

One of the character traits that Charles Baxter seems to dislike most is also the title of the last story in the book, “Vanity.” It features two successful, self-important businessmen who (perhaps significantly) do not live in Minneapolis but are on a plane to Las Vegas, which Baxter has described in another story as “a professionally designed entryway to Hell.” One of these men, Harry, was once a tough, rather admirable young gay man; in “Charity” he essentially saved the life of a former lover, Dennis, who had become a drug addict and a criminal.

Now, however, he seems to lack all human sympathy. When the other businessman, David, asks Harry to do something—to tell him what Las Vegas is like—Harry sends him an e-mail. But his message is merely a vain, self-congratulatory boast of his own present and predicted future success, both financial and sexual. He receives in return three words that seem to come from the author as well as or rather than from David: “Don’t kid yourself.” Which, after all, is one of the lessons of Baxter’s work. The modesty and refusal to kid himself that he shares with many of his characters are admirable traits, but ones that can have unfortunate effects on a literary reputation, which often favors self-deceptive vanity and boastfulness. He deserves to be far better known, and widely celebrated.

This Issue

March 5, 2015

Vaccinate or Not?

Our Date with Miranda

France on Fire