When George Balanchine choreographed A Midsummer Night’s Dream for the New York City Ballet in 1962, he had been living with Shakespeare’s play for most of his life. He was fifty-eight years old and recalled playing an elf or bug in a production when he was a child in St. Petersburg in the years before the 1917 revolution. He liked to say that he knew the play “better in Russian than a lot of people know it in English,” and his dancers remember that he quoted the text in English freely from memory. It was a play, and as importantly a musical score—Felix Mendelssohn’s overture and incidental music—that seemed to follow him through life.

Dream was one of the first original American full-length ballets ever created. The opening performances were on the cramped stage at City Center in New York, but two years later, when the New York City Ballet moved to its new home at the just-constructed Lincoln Center—a monument to New York as the world capital of culture—there was a lavish gala performance celebrating Balanchine’s company as a leading American institution. It opened with a brassy fanfare composed by Igor Stravinsky in honor of the occasion, followed by A Midsummer Night’s Dream.

To some, Dream seemed a surprising choice: for years, although Balanchine continued to make important narrative works, he had made his greatest mark by moving away from the nineteenth-century tradition of narrative ballet and toward a kind of abstraction in dance. In 1951 he had stripped his ballets The Four Temperaments and Concerto Barocco of scenery and elaborate costumes. In 1957 he went further with Agon, a completely plotless dance performed in simple practice clothes on a blank stage against a cyclone blue background to a partly atonal score by Stravinsky. In 1959 came Episodes in a similar vein to an atonal score by Anton Webern. Even the romantic Liebeslieder Walzer the following year had no narrative or story: just Brahms and dancing.

Balanchine was making a political point too. As an émigré who had fled Russia as a young man in 1924, he was profoundly anti-Soviet and well aware that his abstract ballets challenged the prevailing Soviet taste against formalism and for socialist realism in art (“I would have been shot,” he once told one of his dancers). And although the idea for Dream had been with him for decades, he started work on the ballet just two years after the Bolshoi had made a spectacularly successful New York debut to sold-out theaters with a full-length Romeo and Juliet, a Shakespearean dance-drama in a socialist-realist style. While he was choreographing Dream, plans were in the works with the State Department for the New York City Ballet to tour the USSR. Balanchine wanted to take Dream, but the Soviet authorities objected. The company, led by Balanchine, departed for Moscow just months after the New York premiere of his Shakespeare ballet.

Still, when the master of abstraction threw himself and his company into A Midsummer Night’s Dream, some New York critics trained to expect something different were befuddled. They lamented that the play could not be easily translated into a ballet and that Balanchine had turned Shakespeare’s deepest comedy, as The New York Times put it, into “an Easter holiday entertainment.” But Dream really was different. It was not Russian or imperial or nineteenth century; it was—like so many of the dancers who performed it—something quite American. Balanchine was aiming for a new kind of narrative dance that would elegantly present his company in a cold war world. But there was also another, more personal side to Dream that had to do—as it often did in Balanchine’s art—with the women he loved, the Russian world he had lost, and his own sense of exile and aging.

Balanchine was not the first to think of Shakespeare’s play as a ballet. Because A Midsummer Night’s Dream moves between the court and the forest, the “real” social world and a fairy woodland of spirits governed by supernatural forces, it had always seemed a natural choice for ballet and opera adaptations, especially after Mendelssohn composed incidental music for a production of the play directed by Ludwig Tieck for the court in Potsdam in 1843, adding to and filling out his earlier overture to Dream. The play and his music were followed by a steady stream of productions with singing fairies and otherworldly ballerinas in white.

But Balanchine wasn’t interested in this kind of ballet. His production grew instead from his memories of St. Petersburg, where he had first performed the play. This was the Petersburg of the court and the grand Imperial Theaters, but also of avant-garde artists like Vsevolod Meyerhold, who worked at the Imperial Theaters when Balanchine was training there and coming of age. Meyerhold had ideas about theater that Balanchine encountered in various forms from many directions in his early life: in Russia but also in Europe with Serge Diaghilev, Max Reinhardt, and others in the 1920s.

Advertisement

These artists all shared, following Wagner, an idea that theater and opera could be reinvented with dance. They were interested in acrobatics, masks, commedia dell’arte, circus, and pantomime, and wanted to make a new kind of theater that would be impersonal and openly based on artifice. They were against realism and psychological approaches to drama and acting, and preferred instead to begin matter-of-factly with external movements, steps, and gestures; inner feelings would follow. As Balanchine later put it, “Don’t think, just dance.”

Dream drew many of these Russian and European artists. Meyerhold’s theater had mounted a production to Mendelssohn’s music in Russia in 1903, and in 1906 Michel Fokine created a version at the Imperial Theaters. Cocteau’s ballet Parade with Picasso for Diaghilev’s Ballets Russes grew in part from an earlier and unrealized production of Dream, set in a circus ring with Bottom as a clown. Max Reinhardt staged his own Dream some years later in Berlin, revived it many times, and finally made it into a Hollywood film in 1935 using Mendelssohn’s music and starring Mickey Rooney as Puck and Olivia de Havilland as Hermia, with choreography by another Diaghilev colleague, Bronislava Nijinska.

Balanchine knew the film well—perhaps too well. In 1967 he made his own feature-length movie of the ballet, which drew so heavily on Reinhardt’s example that the originality of his own stage Dream all but vanished. The film looked dated even then, and although it has some wonderful and rare footage of dancers (Suzanne Farrell and Edward Villella) it is no substitute for seeing the ballet on its home stage at the New York State (today’s Koch) Theater. (It will be performed there this year in June.)

What was Balanchine’s Dream? He always said it was inspired by Mendelssohn’s music, and the dancer Jacques d’Amboise recalls him experimenting with the score as early as 1943 in a long-since-forgotten outdoor performance. But Mendelssohn’s overture and incidental music were not enough for an evening-length ballet, so Balanchine eventually wove in other Mendelssohn excerpts that seemed to mirror the distinct worlds of Shakespeare’s play: antiquity in the overture from Athalie; the supernatural fairy worlds both in the overture to Der schöne Melusine, a German fairy tale, and in Die erste Walpurgisnacht, inspired by Goethe. For the second-act wedding celebration, Balanchine chose a part of Heimkehr aus der Fremde, composed as an occasional piece in celebration of Mendelssohn’s parents’ silver wedding anniversary. The love pas de deux was drawn from the simple and moving Sinfonia No. 9 for strings, composed by Mendelssohn in a lyrical, self-reflective style when he was fourteen, just a bit older than Balanchine’s Dream elf.

Still, it was not the music alone that made the ballet. To understand Balanchine’s Dream, we have to head straight into the forest, where both the music and the ballet begin. The curtain rises on an empty dew-covered stage, with three thickly ringed trees shimmering in the background and leafy bows growing in from the wings. In a far corner upstage, we see a small spirit-like child poised to dance, bringing to mind Balanchine’s own memory of himself as an elf. The child runs and the stage fills with bugs, butterflies, and fairies, and we soon meet Puck, along with the fairy queen and king, Titania and Oberon.

This beginning is a sharp departure from Shakespeare’s play, which opens decorously at court with a show of pomp and circumstance as Theseus and Hippolyta confront the lovers and impose law and reason over unruly youthful passion. The forest and the fairies come later. For Balanchine, by contrast, Oberon and Titania are the only royal couple that matter and we are already firmly in the realm of the supernatural. It is the forest and the fairies that anchor the life of the ballet. And so Balanchine compresses Shakespeare’s five acts into two and brings everyone—everyone—into the forest and keeps them there, playing out all of their various dramas under the night sky. This reversal of Shakespeare—but also of traditional ballet form, in which the court (the real world) anchors any supernatural flight—was Balanchine’s way of showing where he located the real “real” world.

Balanchine’s forest (designed by David Hayes), moreover, is no ordinary forest. We feel the trees all around, but the stage itself is completely empty. There will be no lovers bushwhacking through branches, brush, cobwebs, and dew-covered trees: in this open and unencumbered space the entire design of the play unfolds with astonishing clarity and the central fact of the play comes immediately to the fore. We see that the lovers are not characters with complex psychological inner lives; they are anonymous impersonal figures, actors who switch and change at first sight for no apparent reason but their own fickle imaginations, addled by a bit of magic.

Advertisement

The story lies in their movements, not in their minds, and Balanchine shows them racing across the stage with great purpose, pursuing, following, chasing, yearning, falling in love and asleep; awaking and running off to do it all again in a different order, with Puck pushing, pulling, orchestrating the whole game in gleeful delight. The mortals don’t even know they are part of a larger design. (“Shall we their fond pageant see?/Lord, what fools these mortals be!”) As we watch the story unfold through pattern and pacing, driven by a musical pulse on a blank stage, we see the trick that Balanchine has played. Dream is an abstract ballet after all.

Act Two comes as a surprise and a letdown. It is strictly ceremonial—we have left the forest and find ourselves abruptly at a full-dress court for the wedding celebrations, stiffly presided over by Theseus and Hippolyta in a milieu that immediately recalls the Imperial St. Petersburg of Balanchine’s childhood imagination, with its elaborate etiquette, formal ballets, and divertissements. In sharp contrast to the vivid, down-to-earth life of the first act, the second feels distant and emotionally detached, like a faded dream image of a beautiful but irretrievable world that doesn’t quite fit or follow the first, which may explain in part why critics have always found it so unsatisfying. The distinct worlds of the play don’t easily mesh in the ballet, and we can feel Balanchine straining against Shakespeare’s consummate skill on the one hand and ballet’s past traditions on the other. It is as if the ballet were telling Shakespeare’s story—and perhaps Balanchine’s own too—backward: Act Two is the old world Balanchine had lost, Act One the forest he had gained.

And yet in other ways Balanchine’s court looks strangely like his forest. The dark woodland trees are still there, shimmering in the distance over the regal balustrade, and when the ballet was later performed in Zurich, Balanchine made a point of asking the designer Peter Harvey (who assisted on the original sets) to please make sure that there were trees growing inside the royal tent too. And would he also create a garden with cypress trees like those from The Lady and the Unicorn tapestries in Paris, stylized to make the forest and the court appear more alike? When the scene melts from the court back into the forest at the end of the ballet, the transformation is so smooth that you can miss it in the glow of fireflies flitting across the stage. We are left feeling uncertain. Did we ever leave the forest, really?

Balanchine’s Dream was filled with people. It was a large company ballet with corps, soloists, and principals, along with children from Balanchine’s school, presented as a family entertainment for all of New York. And if Shakespeare’s play was an enactment of an Elizabethan midsummer festival as an escape from the strictures of quotidian and court ritual into the freedoms of the forest, Balanchine’s Dream was a kind of holiday occasion and affirmation too: a festivity for his company and the city of New York.

The dancers were right at home. They traveled to the forest every day, moving from their individual New York worlds into the rarified atmosphere and dark underbrush of the theater—a tight community of artists working together over long hours in dark and enclosed spaces lit only by “the person of Moonshine,” rushing through hallways from practice studios to dressing rooms and costume fittings, and finally to the stage itself as the dramas of their lives in the theater unfolded. For better and worse, this was their “real” real world with Balanchine, and in this sense it could be said that they had been rehearsing for Dream all of their lives.

For Balanchine, Dream was about Shakespeare and Mendelssohn, but it was also about them and the world he and his company had created together at his theater. It was deeply personal; in his mind, life and art were never far apart. And so Titania was not just a character in a play, she was a dancer he loved—a role that could no longer be taken by his young wife and past muse, Tanaquil LeClerq, who had been stricken some years before with polio and confined to a wheelchair. After a long period of trying to rehabilitate her, Balanchine by now understood that she would never fully recover, and he had in any case long since fallen in love with another dancer: the remote and unattainable Diana Adams. It was Adams whom he cast as the beautiful Titania in Dream.

Shakespeare had drawn this character in part from Ovid: “Titania” was Ovid’s other name for Diana in his retelling of the Diana and Actaeon story. Ovid calls her “Titania” at the precise moment when the hunter Actaeon enters her grove and sees her bathing—an erotic trespass for which he is punished by being turned into a stag (Shakespeare’s ass) and then ripped apart by his own dogs.1 Diana, moreover, is the goddess of the moon (shining over the midsummer night and lighting the theater), and of hunting and chastity—a sensual chastity of dewy greenery and nature. Balanchine framed his Diana in what he called her “Primavera” throne, referring to Botticelli’s painting and probably also to the shell—a near replica of the one in the ballet—in the painter’s Birth of Venus.

In a further sign of the role’s importance in his mind, Balanchine also asked the young Suzanne Farrell—who would become the next great love in his life—to learn the part of Titania. As it turned out, Adams was indisposed when the ballet opened and Melissa Hayden, a seasoned performer who could be relied upon to carry the show, stepped into the role—which soon passed to Farrell, with whom Balanchine was by then romantically involved (he took her to a Botticelli exhibition in Paris, telling her that she looked like Venus herself). Shortly before his death, Balanchine gave many of his ballets to people he loved and cared for: Dream went to Diana Adams.

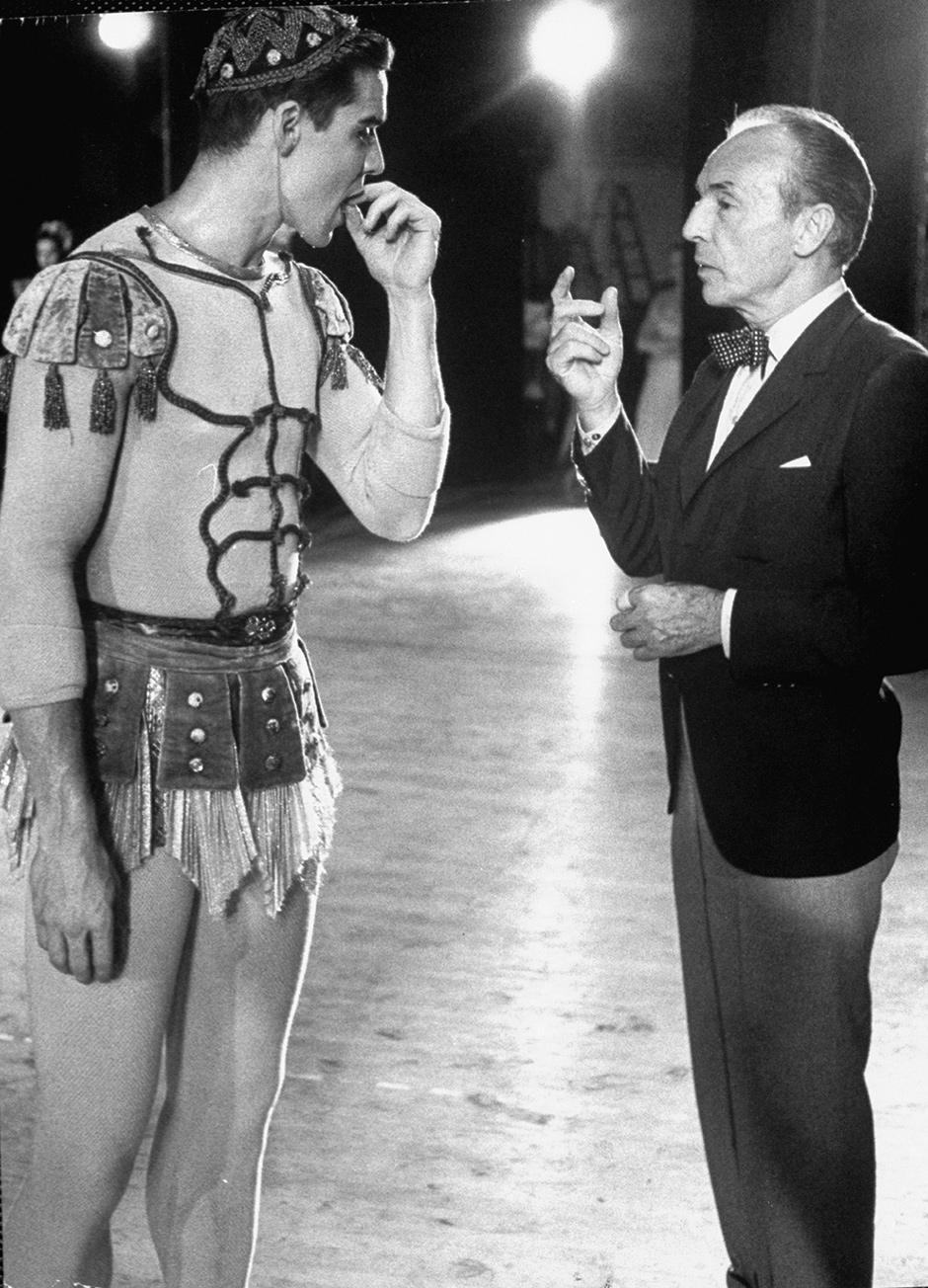

Oberon was danced by Edward Villella, which initially seemed a surprising choice to many of the dancers, including Villella himself. This muscled street kid from Bayside, Queens, a former boxer who had also trained at the Merchant Marine Academy, seemed an unlikely match for a kingly role—or for the regal (and much taller) Adams. But Balanchine thought otherwise. He wanted a shorter Oberon in keeping with literary traditions (cursed with stunted growth, Oberon was known as the “little king”).

Villella, moreover, came from a traditional Catholic Italian émigré family, and his machismo depended on a strong code of manners that included courtly deference to women and a host of family and community rites and obligations. He remembers watching his grandfather, “il Padrone, the giver, the pourer of the wine,” conducting their clan in traditional Sunday festivities—a kind of Italian midsummer night’s ritual. If Villella saw Balanchine as the Padrone of the NYCB, Balanchine saw Villella as the natural ruler of Dream. The scherzo that he danced so brilliantly demanded nobility, power, and (as Villella put it) “super-human” technical accomplishment, making him the perfect otherworldly patriarch.

Puck was traditionally a hobgoblin or demon, but he was also thought to have been a house spirit—sweeping the stage with a broom—who helped women with their chores and their romantic quandries. In this role, Balanchine cast Arthur Mitchell, the company’s only black dancer at the time, telling him his dark skin would make him seem to disappear into the trees and the forest night. They fussed over his costume, and Balanchine kept saying it was all too cumbersome and Mitchell shouldn’t wear much of anything. Finally Mitchell went home one night, traced his muscles with Albolene cream and sprinkled his gleaming bare skin with glitter—like dew—which delighted Balanchine: “Now my dear, you look expensive.”

The lovers, like those in the play, were drawn from among his favored dancers—Patricia McBride and Jillana, to start with, and later Karin von Aroldingen, Sara Leland, and Mimi Paul, among others. As for the Amazonian Hippolyta, she could only be Gloria Govrin, “Big Glo,” strong, sexy, full-figured. This was no captive bride but a powerful, erotic dancer, a force of disruption and the leader of the hunting dogs, which tear across the stage like furies in the storm of Act One, bringing to mind the dogs that destroyed poor Actaeon.

So the play was not only a play; it was his dancers and their lives too. It could even be said that casting was Balanchine’s answer to acting. Like Shakespeare’s characters, the dancers were not given motivations or “backstories”; the pattern of their own lives was enough to help them (and him) find their roles. Moreover, the idea of the mask freed them all. Bottom was transformed when Puck placed the ass’s “noll” (head) over his own—and yet underneath (and the mask never lets us forget that there is an underneath) Bottom is still very much himself. The dancers too were always themselves underneath, which paradoxically made their dancing even more direct and alive. Dream was Balanchine’s, but it was theirs too. His choreography told them where to go and what to do, but never what to feel.

If Balanchine imagined himself in a role in Dream, it was surely Bottom, Shakespeare’s simple weaver and amateur actor turned ass. The role was first danced by Roland Vasquez but quickly taken over by Richard Rapp, who at times served as a kind of Balanchine cipher, later taking his place, for instance, as the Don in Don Quixote, and here stepping in as the love object of the coveted Titania. The pas de deux between Titania and Bottom is among the most poignant moments in the ballet: here is Balanchine’s goddess Diana, feeding, caressing, adoring her awkward and very mortal ass. It is an unlikely dance of shared domesticity, but also a fantasy of a younger beauty doting unconditionally on an aging man. It is perhaps not surprising that the ballet’s Bottom brings to mind Balanchine’s own sweet self-portraits, sent in love letters sometime in these years to his beleaguered Tanny: there he is, a modest and attentive mouse, in a state of wishful domestic bliss and service to an imposing and regal cat. It was like that with Bottom and Titania too.

In the ballet, Bottom’s love doesn’t disappear when Puck removes his ass’s head. He may not in the play be able to describe his “most rare vision” that “hath no bottom,” but Balanchine certainly tried. The awkward and touching first act pas de deux finds its other half in a beautiful second act pas de deux, performed in the film of the ballet by Allegra Kent, another woman who fascinated Balanchine, with Jacques d’Amboise, another man who sometimes seemed to “act” the choreographer.2 Only this time, the lovers are not an unlikely pair acting under a magic spell, but instead young, themselves, and consciously absorbed in a moment of genuine intimacy. There is nothing formal about the dance, no wedding march or public declaration of love; it is more like a couple knowing each other for the first time, shyly touching, finding their balance together, arms interlacing to Mendelssohn’s simple and lyrical phrasing.

As to the meaning of it all, Balanchine loved to quote Bottom, noting with pleasure Shakespeare’s clever play on Saint Paul’s First Epistle to the Corinthians:

The eye of man hath not heard, the ear of man hath not seen, man’s hand is not able to taste, his tongue to conceive, nor his heart to report, what my dream was.

“What Bottom says,” Balanchine later explained in an interview, “sounds as if the parts of the body were quarreling with each other, but it’s really as if he were somewhere in the Real World. He loses his man’s head and brain and experiences a revelation.” A “revelation,” that is, without words, which is what Balanchine believed dance might also achieve, and why words could never describe it.

It is also why his second act faltered. He knew he couldn’t convey in dance what Shakespeare’s “mechanicals” achieve in their play-within-a-play, so he cut the play and made a ballet-within-a-ballet instead: the sublime pas de deux, which truly is “without bottom.” And if it didn’t quite work as a translation, Balanchine seemed to know that his second act hadn’t managed to rise to Shakespeare’s (or Bottom’s) mark. He later said that he had wanted to follow the court entertainment with something more, “a big vision of Mary standing on the sun, wrapped in the moon, with a crown of twelve stars on her head and a red dragon with seven heads and ten horns…the Revelation of St. John!” He didn’t do it because “nobody would understand it…people would think I was an idiot. ”

What we are left with is a wonderful but flawed ballet—two acts that don’t quite go together or achieve what Balanchine hoped they might. Yet what he does accomplish in the first act is so deeply entertaining, so human and life-affirming—and clearer even than Shakespeare—that it is hard to find much fault. After all, A Midsummer Night’s Dream was part of a larger narrative that preoccupied Balanchine for most of his life: Russia and the nineteenth century, the sight and study of beautiful and unattainable women, humility and his own mortality; not to mention the play of circus, masks and commedia dell’arte, and the possibility of spiritual revelation in music and dance.

It wasn’t the last time he would give himself over to these great themes or to the stories of Western art: Don Quixote, an ambitious full-length work to an original score, followed in 1965 and one of Balanchine’s final works was another narrative dance and portrait of an artist, Robert Schumann’s Davidsbündlertänze, which premiered in 1980, three years before his death. A Midsummer Night’s Dream was the first. It was a ballet, but it was also where he came from and what he believed in. It was a bow to Shakespeare’s rare vision and to all that “hath no bottom” and cannot be said.

This Issue

March 5, 2015

Vaccinate or Not?

Our Date with Miranda

France on Fire

-

1

See especially Leonard Barkan, “Diana and Actaeon: The Myth as Synthesis,” English Literary Renaissance, Vol. 10, No. 3 (September 1980). ↩

-

2

The second act pas de deux was choreographed on Jacques d’Amboise and Violette Verdy, although the opening night was danced by Verdy with Conrad Ludlow (d’Amboise was out). Allegra Kent understudied and later took on the role; you can see her performance with d’Amboise in the film of the ballet. ↩