Never underestimate the persistence of opponents of President Barack Obama’s signature legislative achievement, the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (ACA). Since the law was enacted in 2010, Republicans have introduced countless bills to repeal it, but have never had the votes to make their efforts anything but symbolic.

Having lost in the legislature, Obama’s opponents—many of them the very same conservatives who have long decried judicial activism—turned to the courts. In 2012, they lost a constitutional challenge to the ACA, when Chief Justice John Roberts parted company with his conservative colleagues and wrote a majority opinion holding that Congress’s power to impose and collect taxes authorized it to require individuals either to purchase health insurance or to pay a tax. The decision roiled the conservative movement, not least because of rumors that Roberts had initially voted to strike down the law, only to change his mind in the course of writing the opinion.

Now the Obamacare opponents are back before the Supreme Court again, advancing another challenge that, if successful, could spell the end of the ACA. King v. Burwell, or “Obamacare, Round 2,” will be argued on March 4. It pits Michael Carvin, one of the lawyers who argued the first challenge, against Solicitor General Don Verrilli, who successfully defended the law. Burwell has received far less attention than the earlier case, in part because it makes no constitutional claims and presents only a question of statutory construction. But its implications could be just as momentous.

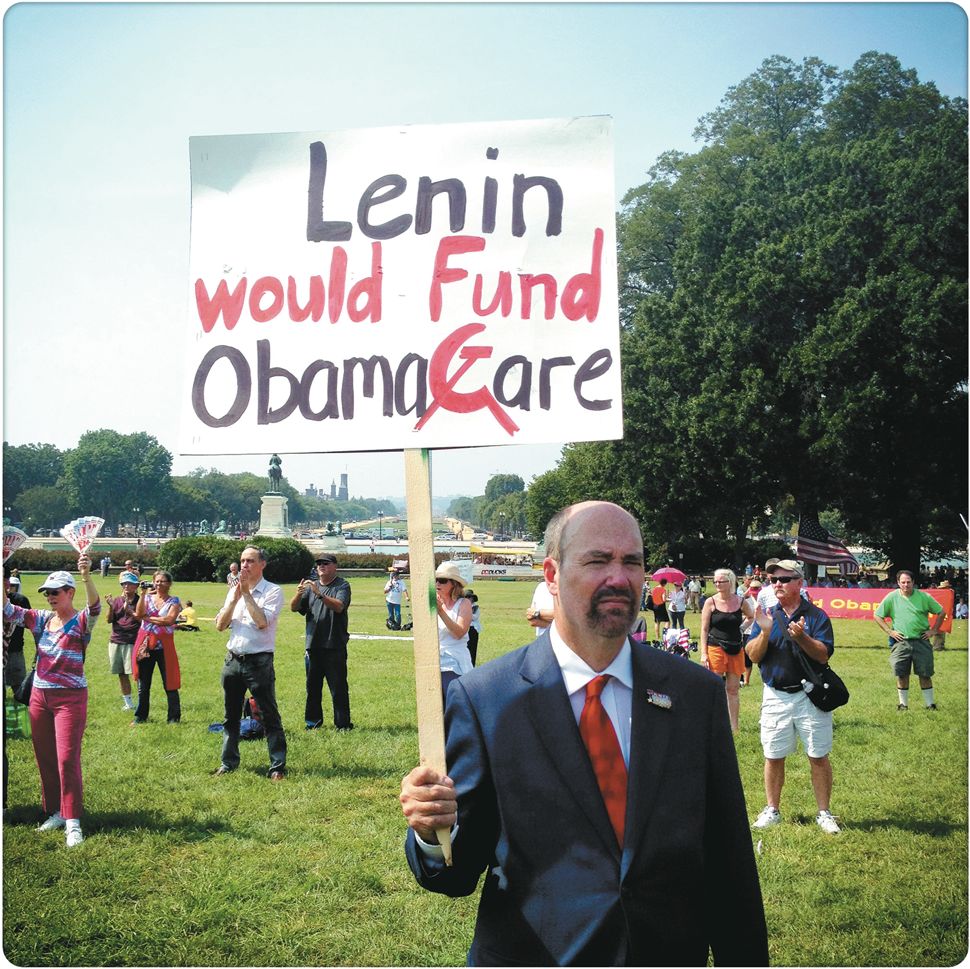

The lawsuit is being funded by the Competitive Enterprise Institute, whose board member and former chairman, Michael Greve, had this to say about the ACA at a conference in 2010:

This bastard has to be killed as a matter of political hygiene. I do not care how this is done, whether it’s dismembered, whether we drive a stake through its heart, whether we tar and feather it and drive it out of town, whether we strangle it. I don’t care who does it, whether it’s some court someplace, or the United States Congress. Any which way, any dollar spent on that goal is worth spending, any brief filed toward that end is worth filing, any speech or panel contribution toward that end is of service to the United States.

The day that the Supreme Court rejected the constitutional challenge to the ACA, lawyers working with the CEI held a conference call about moving ahead with this new statutory claim.

This time, the law’s opponents seize on a single phrase buried in a subclause of the tax code that was amended by the ACA. They argue that it has the effect of denying to low- and middle-income taxpayers in thirty-four states the tax credits and subsidies designed to assist them in purchasing health insurance. Those thirty-four states elected to have the federal Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) create their insurance exchanges, rather than running the exchanges themselves, as the ACA expressly permitted. An exchange is essentially a state-specific market, generally accessed online, for individuals and small businesses to purchase health insurance.

The lawsuit contends that residents of these thirty-four states are ineligible for federal tax credits, which it argues are available only to those who purchase insurance on an exchange established by the state. An Urban Institute study reports that if the challengers prevail, approximately nine million Americans would lose almost $29 billion in tax credits—an average of about $3,000 per person. As the subsidies are available to individuals who earn between $11,500 and $46,680 a year, all of those affected would be poor or middle-income: they would include “day-care aides, waiters, bartenders and retail clerks…the self-employed…[and] early retirees.”1 And the insurance markets in these states would then be destroyed, because many people would no longer be able to afford insurance, which would reduce the pool of persons covered and increase the cost of insurance for all state residents to prohibitive levels.

The challengers’ statutory argument is deceptively simple. A subclause of the tax code setting forth a formula for calculating federal income tax credits provides that the amount of the credit depends on the number of months the taxpayer has been enrolled in a health insurance plan purchased on an insurance exchange “established by the State.” Since an exchange established by the federal HHS is not an exchange “established by the State,” they maintain, the law precludes subsidies for all residents of the thirty-four states that have exchanges created by HHS. The government counters that “exchange established by the State” is a legal term of art, and when read in conjunction with other parts of the ACA, it encompasses both exchanges that states themselves established, as well as exchanges that the states chose to have HHS create for them in their respective states.

Advertisement

The challengers do not dispute that, were the Court to adopt their reading, the insurance markets would fail in two thirds of the states. (Indeed, that is their hope, as it would mark the end, albeit a painful and ugly one, of Obamacare.)

The challengers insist, however, that courts must enforce the plain meaning of the statute’s terms, and cannot rewrite them to serve some larger general purpose, such as providing affordable health care to “all Americans,” the expressly stated purpose of the ACA. They cast the case as “extraordinarily straightforward”: an exchange established by HHS is not an exchange established by the state.

At first glance, this argument might well be thought to appeal to the Court’s five conservative justices. After all, four of them—Justices Anthony Kennedy, Antonin Scalia, Clarence Thomas, and Samuel Alito—are already on record as believing that the ACA is unconstitutional. And as a methodological matter, the conservative justices tend to favor “textualism” or “strict construction” over more open-ended, or “purposive,” methods of interpretation. Thus, this challenge appeals to a conservative doctrine of statutory interpretation to attack a statute that conservatives already find troubling for other reasons.

When the Court agreed to hear the current case in November 2014, without waiting to see if the lower courts divided on the question, some observers saw this as a sign that the conservative justices were reaching out to avenge their “loss” in the first ACA case. In The New York Times, Linda Greenhouse wrote that the grant of review was more troubling than Bush v. Gore, in which the Court effectively called the 2000 election for George W. Bush.

So is the ACA doomed? I don’t think so. First of all, the Court’s decision to hear the case is not necessarily a sign that it will agree with the challengers. There is a strong prudential reason for hearing the case as soon as possible: the ACA is a huge and complicated program, and millions of people are relying on it for their health insurance. Whether the end result of this case is that millions of Americans are deemed eligible or ineligible for the act’s federal subsidies, it’s surely better to resolve that question sooner rather than later. And the challengers, who had already filed multiple cases, could be counted upon to keep filing until they prevailed in some court of appeals. Had the Court stayed its hand, it would have left doubts about the validity of the law for years to come. Under the circumstances, the grant of review is not a sign of overreaching by the Court, or that the challengers will prevail.

Second, the challengers’ argument loses its superficial appeal—and becomes decidedly anticonservative—as soon as one looks beyond the single phrase they focus upon, and considers how that phrase is understood in the context of the statute as a whole. Even the most conservative “textualists” agree that the judge’s job is, as the Court has said, to discern “the plain meaning of the whole statute, not of isolated sentences.”2 Justice Scalia, the high priest of textualism, has advised that “in textual interpretation, context is everything.”3 Or as one of America’s greatest jurists, Learned Hand, once warned, “Sterile literalism…loses sight of the forest for the trees.”4

The challengers in King v. Burwell have indeed lost sight of the forest for the trees. It is a cardinal rule of statutory interpretation that statutes should not be interpreted to achieve absurd ends, yet that is precisely what the challengers’ reading would produce. If their interpretation of the single phrase they rely upon is correct, many other sections of the statute would make no sense at all, and indeed the HHS exchanges that Congress expressly authorized would be doomed to fail.

If the challengers’ view were correct, the HHS exchanges would have no one to sell insurance to, and no insurance to sell. Because the ACA defines an individual “qualified” to purchase insurance from an exchange as one who “resides in the State that established the Exchange,” exchanges created by HHS would have no eligible customers. And because the law similarly defines “qualified” health plans that can be sold through the exchange, the HHS exchanges would have no health plans to sell. The exchanges would be empty shells serving no one.

Moreover, even if these problems could somehow be finessed, the HHS exchanges would be doomed from the outset. The ACA rests on three pillars. It (1) prohibits insurance companies from discriminating on the basis of preexisting conditions, (2) mandates that all persons who can afford to do so must purchase insurance or pay a tax, and (3) provides subsidies to the many people who could not otherwise afford insurance. All three pillars are necessary for the ACA to work.

Advertisement

In the 1990s, several states prohibited insurance companies from discriminating on the basis of preexisting conditions without mandating the purchase of insurance or subsidizing those who could not afford it. In each instance, the result was a “death spiral” in which insurance became prohibitively expensive, and the insurance markets collapsed. Healthy people could and did rely on the nondiscrimination rule to wait to purchase insurance until they were ill. The pool of insured was then dominated by the elderly and the sick, and without a larger pool to share the risks and costs, insurance companies had to raise prices for everyone. That, in turn, meant fewer people could afford insurance, which reduced the numbers sharing the risk still further, and caused insurance fees to rise still higher. So Congress knew that the only way to achieve a working insurance market with a nondiscrimination rule was to ensure broad participation through the individual mandate and tax subsidies.

It would have made no sense for Congress to give states the choice to allow HHS to create exchanges for them, but then deny to all customers of those exchanges the subsidies necessary to make the market work. If “exchange established by the State” is read, by contrast, as the federal government contends, to include exchanges in states that elected to have HHS create their exchanges for them, none of these absurd results obtain, and the scheme operates, as intended, to provide health insurance to “all Americans.”

In search of a rationale that might explain their interpretation, the challengers posit that Congress was trying to encourage states to create their own exchanges by penalizing them if they did not—even though not a single member of Congress suggested as much, and even though the states themselves did not foresee that result. It is not uncommon for the federal government to condition grants to states on their engaging in certain types of activity, and the challengers argue this is simply an instance of such “conditional spending.” But there are several problems with this argument.

First, if Congress was indeed seeking to impose a condition on the states, this was a peculiar and impermissible way to do so. Under a constitutional doctrine designed to protect the states, the Court has said that when Congress seeks to impose conditions on states, it must do so “unambiguously,” so that the states have clear notice of the implications.5 If there is any ambiguity, therefore, the statute is to be read as not imposing a condition on the states. Here, the challengers would have the court ignore that doctrine and instead treat the statute as a game of “gotcha,” relying on a few obscure words buried in a subclause of the tax code directed not to states at all, but to individuals as federal citizens, concerning the computation of their federal taxes. Indeed, when Jonathan Adler and Michael Cannon, two of the architects of this legal challenge, first wrote about the issue in The Wall Street Journal, they characterized the statutory language as a “glitch.”6 That is not how Congress imposes conditions on the states.

Second, Congress set forth the option for HHS to establish an exchange for the state in a provision entitled “State Flexibility Relating to Exchanges.” That provision nowhere even intimates that if a state were to take advantage of this “flexibility,” its residents would lose their eligibility for tax benefits, and the state’s insurance market would be destroyed. The challengers’ interpretation would transform a provision designated as offering states “flexibility” into a coercive threat to punish the states’ residents.

Third, a friend of the court brief filed by twenty-two of the states that exercised their “flexibility” to allow HHS to establish an exchange observes that the states themselves never saw this coming. They expended considerable resources studying how best to implement the ACA, yet “conspicuously absent from the Amici States’ deliberations was any notion that choosing an [HHS exchange] would deprive citizens of tax credits.”

At best, then, the meaning of an exchange “established by the State” is ambiguous. Taken on its own, and ripped from the context of the statute as a whole, the reference to the “state” might well be understood to preclude HHS exchanges. But when read in context with other provisions that define the exchanges, their duties, and their purposes, the phrase can only be understood as a legal shorthand that includes both exchanges established by the states themselves and exchanges established for the states by HHS at the state’s election. Where a statute is ambiguous, another doctrine long favored by conservatives requires the courts to defer to the interpretation of the executive agency charged with implementing it. In this instance, the IRS has issued regulations that interpret the tax code provision in question as authorizing tax credits to customers using HHS exchanges. If there is any ambiguity at all, the Court must defer to that judgment.

As Michael Greve’s quote above illustrates, the intentions of the law’s opponents are clear. They want to kill Obamacare. In theory, a statutory decision by the Court could be fixed by Congress amending the ACA, or by the states establishing their own exchanges. But as Michael Cannon gleefully told an audience at Georgetown University Law Center on February 11, 2015, political opposition will ensure that no such fix is possible, at the federal or state level. The fate of the law turns, therefore, on the Supreme Court’s interpretation of “established by the State.”

The challengers have sought to portray their case as based on conservative ideals. That is a ruse. To rule in their favor would in fact require the Court’s conservative justices to abandon three fundamental, and ultimately conservative, legal principles—that courts must interpret statutes to give meaning to the whole; that states’ rights concerns require Congress to be unambiguous when it imposes conditions on the states; and that courts should defer to agencies in the interpretation of the statutes that they implement. Instead, the challengers would have the Court adopt an interpretation, focused on four words wrenched out of context, that produces absurd results, imposes a highly coercive condition on states virtually by subterfuge, and overrides the plainly reasonable interpretation adopted by the IRS.

But perhaps the least conservative aspect of a ruling in the challengers’ favor would be its result—it would radically upend the status quo, and would mark the first time in the Court’s history that it issued a decision taking tax benefits away from millions of poor and middle-class Americans. It is of course possible that partisan opposition to Obamacare will drive the Court’s conservative justices to reach such an anticonservative result. But if they do, they will be acting contrary to their own principles.

This Issue

March 19, 2015

The Road from Westphalia

2016: The Republicans Write

-

1

Linda J. Blumberg et al., “The Implications of a Supreme Court Finding for the Plaintiff in King v. Burwell: 8.2 Million More Uninsured and 35% Higher Premiums” (Urban Institute, January 2015). For a powerful account of the real people who stand to lose their insurance benefits if the lawsuit prevails, see Lena H. Sun and Niraj Chokshi, “Millions at Risk of Losing Coverage as Justices Take Up Challenge to Obamacare,” The Washington Post, February 16, 2015. ↩

-

2

Beecham v. United States, 511 U.S. 368, 372 (1994). ↩

-

3

Antonin Scalia, A Matter of Interpretation: Federal Courts and the Law (Princeton University Press, 1997), p. 37. ↩

-

4

New York Trust Co. v. Commissioner of Internal Revenue, 68 F.2d 19, 20 (2d Cir. 1933). ↩

-

5

Pennhurst State School and Hospital v. Halderman, 451 U.S. 1, 17 (1981). ↩

-

6

Jonathan H. Adler and Michael F. Cannon, “Another ObamaCare Glitch,” The Wall Street Journal, November 16, 2011. ↩