When Bob Hope died in 2003 at the age of one hundred, attention was not widely paid. The “entertainer of the century,” as his biographer Richard Zoglin calls him, had long been regarded by many Americans (if they regarded him at all) “as a cue-card-reading antique, cracking dated jokes about buxom beauty queens and Gerald Ford’s golf game.” A year before his death, The Onion had published the fake headline “World’s Last Bob Hope Fan Dies of Old Age.” Though Hope still had champions among comedy luminaries who had grown up idolizing him—Woody Allen and Dick Cavett, most prominently—Christopher Hitchens was in sync with the new century’s consensus when he memorialized him as “paralyzingly, painfully, hopelessly unfunny.”

Zoglin, a longtime editor and writer for Time, tells Hope’s story in authoritative detail. But his real mission is to explain and to counter the collapse of Hope’s cultural status, a decline that began well before his death and accelerated posthumously. The book is not a hagiography, however. While Zoglin seems to have received unstinting cooperation from the keepers of Hope’s flame, including his eldest daughter, Linda, he did so without strings of editorial approval attached. Hope’s compulsive womanizing, which spanned most of his sixty-nine-year marriage to the former nightclub singer Dolores Reade (who died at 102, in 2011), is addressed unblinkingly. And with good reason—it was no joke. At least three of his longer-term companions, including the film noir femme fatale Barbara Payton and a Miss World named Rosemarie Frankland whom Hope first met when she was eighteen and he was fifty-eight, died of drug or alcohol abuse.

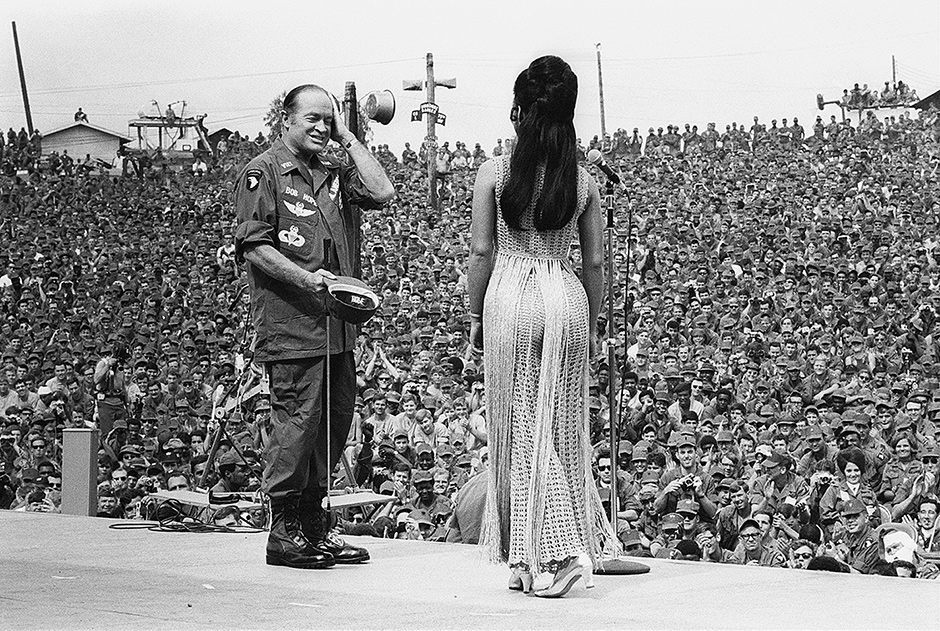

Zoglin is no less forthright in recounting Hope’s political sideline as a shill for Richard Nixon and Spiro Agnew. The book’s descriptions of his appearances before American troops in wartime, some of them entailing real physical risk, are balanced by less savory episodes such as Hope’s fronting for “Honor America Day,” a Washington propaganda rally staged by the Nixon White House to try to drown out national outrage over the Cambodian invasion and the Kent State University killings in 1970.

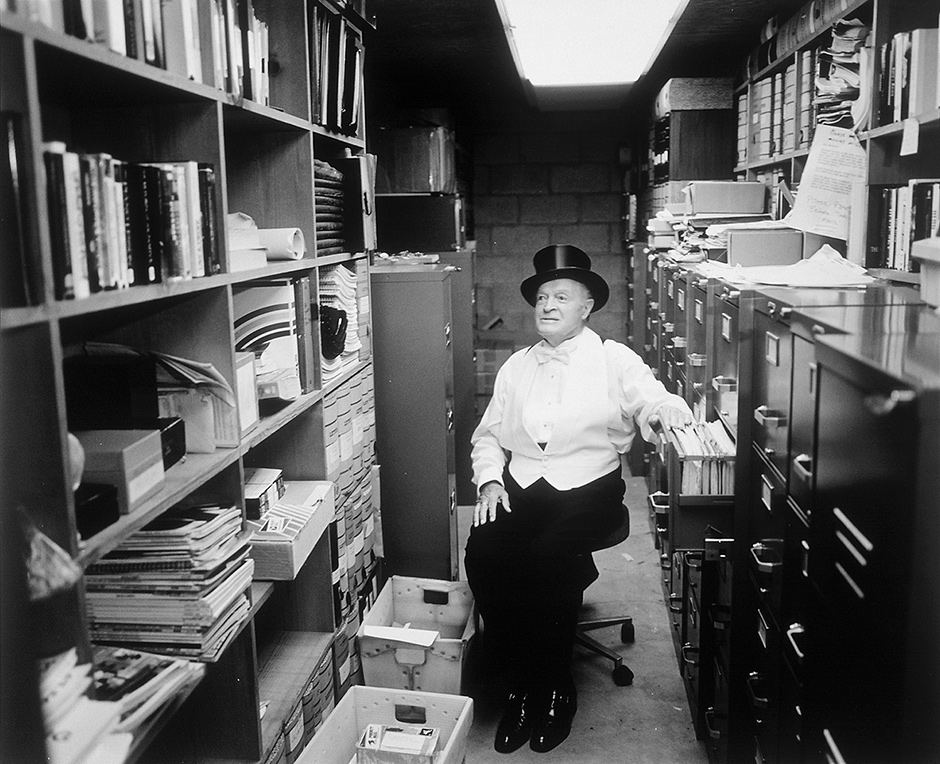

Hope’s family and former colleagues no doubt opened up their memories and archives for the simple reason that they, too, are flummoxed by his fast fade from the American consciousness. The many official monuments to Hope’s name—streets from El Paso, Texas, to Branson, Missouri; American Legion posts from Okinawa to Miami; an airport in Burbank; a bridge in Cleveland; a navy cargo ship; an air force transport plane—have failed to stop the erosion of his legacy. Speaking candidly to a fair-minded biographer is a small price to pay for the prospect of a restoration.

These days few readers may know or remember just how big a deal Hope was in his prime. To make his case, Zoglin must marshal a blizzard of irrefutable statistics (radio and television ratings, box-office grosses) and a touch of hyperbole. The scope of his achievement is “almost unimaginable,” he writes. Hope was both “the most popular” and “the most important” entertainer of the twentieth century, “the only one who achieved success—often No. 1-rated success—in every major genre of mass entertainment in the modern era: vaudeville, Broadway, movies, radio, television, popular song, and live concerts.”

Zoglin further credits him with “essentially” inventing “the modern stand-up comedy monologue,” and with being “largely responsible” for “setting the parameters” for what it means to be a celebrity in “the age of celebrity.” Hope didn’t so much set those parameters as expand them, devising ever more brazen entrepreneurial innovations to monetize his career. He was the first star to coerce movie studios and television networks into ceding ownership stakes in his movies and television shows to his own production company; the first to market himself as a brand, complete with his own logo and annual golf tournament; the first to tirelessly leverage his good works for image-enhancement as well as charity.

Hope’s greatest gift may have been for self-promotion. He was not one to turn away a single potential customer. In his zeal to plug every upcoming movie or television enterprise, he would grant advance interviews to anyone with a microphone, notepad, or camera. For years, he had his own syndicated column in the Hearst papers. He answered “an amazingly high proportion” of his fan mail and would gladly stop to chat with any fan or autograph seeker who crossed his path. “As an entertainer,” Zoglin writes, “he was the greatest grassroots politician of all time.” Had Hope lived in the digital era, he might have been too busy posing for selfies to find time to do anything else.

He was born Leslie Towns Hope in Eltham, England, in 1903, the fifth of seven sons raised hand-to-mouth by a hard-drinking stonemason and his orphaned, poorly educated Welsh wife. The family emigrated to Cleveland via Ellis Island when Bob was four-and-a-half. His Horatio Alger ascent from near poverty to stardom in ever-expanding modern show business is of a piece with many of his contemporaneous immigrant peers. He tried several callings along the way, from boxing to hoofing, before finding success as a partner in comedy teams. From an apprenticeship on bottom-rung vaudeville circuits, he graduated to the big time on bills headlined by the likes of Roscoe “Fatty” Arbuckle and the Hilton sisters, the conjoined twins later to be enshrined in Tod Browning’s film Freaks.

Advertisement

Hope’s first break as a solo comic of sorts arrived by chance during a lowly three-night engagement in New Castle, Pennsylvania, in 1927. Asked by the theater manager to announce next week’s show at the signoff of his and his partner George Byrne’s act, he noted that the coming headliner, Marshall Walker, was a Scotsman. “I know him,” Hope continued. “He got married in the backyard so the chickens could get all the rice.” That gag—built on a stereotype yet inoffensive—could well have been in a Hope monologue three decades later. It got a laugh, and the theater manager asked him to keep it up for the rest of the engagement. Hope improvised more jokes each time, a first step down the road toward his most enduring role, as a wisecracking master of ceremonies for all occasions.

Emcees and comic monologists were novelties in 1920s vaudeville. Two early examples, Frank Fay and Will Rogers, were Hope heroes and influences. But before Hope’s own joke-crammed monologues would become the focus of his energy and the fulcrum of his triumphs in radio and television, he conquered Broadway as a musical comedy performer. In The Ziegfeld Follies of 1936, in which he appeared with Fanny Brice, Josephine Baker, and the Nicholas Brothers, he introduced the Vernon Duke–Ira Gershwin standard “I Can’t Get Started.” Months later he and Ethel Merman did the same for Cole Porter’s “It’s De-Lovely” in the musical Red, Hot and Blue.

Hope’s Hollywood career, at first mired in forgettable shorts after a disastrous 1930 screen test at Pathé, took off soon after. In The Big Broadcast of 1938, he and Shirley Ross were cast as a divorced couple who meet again on a transatlantic ocean liner and sift through the ashes of their marriage in the duet “Thanks for the Memory.” To Zoglin, “it is one of the most beautifully written and performed musical numbers in all of movies.” Beautiful or not, this five-minute-plus piece of film gave Hope a career-long theme song and transformed him into a star. The series of buddy movies he made with Bing Crosby, the most durable achievements of his career, would begin two years later, with Road to Singapore, and continue for more than two decades before petering out with The Road to Hong Kong in 1962.

The best of the Road films remain fun. Hope created a lasting comic persona as the insecure patsy to the more debonair Crosby, his partner in small-time con games and his perennial rival for the affections of Dorothy Lamour. Hope’s exquisite timing, honed on the road and in radio (where he was nicknamed Rapid Robert), is more memorable than the dialogue it punctuates—a syndrome that would continue in his television monologues. (Almost every extant Hope performance on film or television can be found on YouTube, some of it facilitated by the Hope estate.)

Yet for all the irreverence in the Hope–Crosby volleys, they lack an anarchic comic edge. When Hope approached Neil Simon in the early 1970s about securing the film rights to The Sunshine Boys for him and Crosby, the playwright’s rejection was telling. Simon wrote to Hope that his title characters, feuding ex-vaudeville partners, were based on the old team of Smith and Dale. “Not only are their appearance, mannerisms and gestures ethnically Jewish,” Simon explained, “but more important, their attitudes are as well.”

In reality, non-Jews have often starred in The Sunshine Boys on stage, starting with Jack Albertson in the original Broadway production. The “attitudes” Simon found missing in Hope and Crosby had more to do with comic sensibility than ethnicity. There’s a certain vanilla smoothness to their shtick, even when their characters are in jeopardy; the tone is the antithesis of the high anxiety of a Sunshine Boy or Marx brother. When the Los Angeles Times proclaimed Hope “the world’s only happy comedian” in 1941, it was meant as a compliment, but many of Hope’s brethren would have found the very notion of a happy comedian a contradiction in terms.

Advertisement

As Zoglin observes, Hope was the rare Hollywood star of his stature who never worked with a major film director. That in itself is a verdict on his lack of elasticity as an artist. In their afterlife, the Hope–Crosby movies have never enjoyed the cachet of the Marx Brothers films, let alone the Chaplin and Keaton classics. They don’t turn up often at film societies or revival houses and don’t receive deluxe DVD restorations. Even as ardent a Hope fan as Woody Allen puts a ceiling on his praise. Speaking to Zoglin about one of Hope’s better non-Road films, Monsieur Beaucaire (1946), Allen observes that while Hope was “a wonderful comic actor,” he “was not a sufferer, like Chaplin, or even as dimensional as someone like Groucho Marx, who suggested a kind of intellect. Hope was just a superficial, smiling guy tossing off one-liners. But he was amazingly good at it.”

Hope’s real comfort zone as an entertainer was not in film, television, or radio. (“It all seemed so strange, talking into a microphone in a studio instead of playing in front of a real audience,” he once said of his earliest broadcasting experiences.) It was live performance that galvanized him—or, to put a finer point on it, vaudeville, the medium where he started. Not for nothing did he and Crosby often play vaudevillians in the Road movies, or did Hope tour obsessively throughout his career, playing any civic auditorium, college campus, military base, charitable or corporate function that would book him. As late as 1983, the year he turned eighty, he did eighty-six stage shows, forty-two charity benefits, and fourteen golf tournaments on top of his active television career.

“When vaudeville died, television was the box they put it in,” Hope joked. When he arrived in the new medium, he simply resurrected the old format, much as he had also done in radio. In lieu of the sketch-heavy comedy revue forged by Sid Caesar, Imogene Coca, and their band of second bananas in Your Show of Shows, or the half-hour sitcoms embraced by Lucille Ball, Jackie Gleason, and Phil Silvers, he alighted on the television “special,” in which he served as the emcee introducing and intermingling with the variety acts. The one-liners of his opening monologue became the be-all and end-all of his comic energy, even though, as Zoglin writes, “the jokes were always the weakest part of his act” and it was the delivery that carried the day. Hope carried this formula over to his record number of appearances as an Oscar show host (nineteen, including his co-host stints), his annual Christmas visitations with the troops (which would then be packaged as specials), and his guest appearances on other television programs with their own monologists, like Johnny Carson’s Tonight Show.

To his credit, Hope was, as Zoglin says, “the first comedian to openly acknowledge that he used writers”—as many as a dozen at a time. (Unintentionally, he was also among the first to acknowledge his complete dependence on cue cards; his darting eyes track their off-camera whereabouts just as glaringly whether he’s appearing in Burbank or Danang.) Many if not most comics of his day used writers, of course, but Hope did so to an unusual degree. According to Zoglin, only a few moments in the profuse fourth-wall-breaking exchanges between Hope and Crosby in the Road movies were ad libs. Little else was improvised either:

The writers were responsible for virtually everything Hope said or that appeared under his name. They wrote his TV shows, monologues for his personal appearances, magazine articles that carried Hope’s by-line, jokes that were fed to columnists such as Variety’s Army Archerd, acceptance speeches, commencement addresses, and eulogies. When Hope was a guest on other TV variety shows, he would get the script in advance and have his writers add new lines that he could throw into the sketches during rehearsals. (His practice of rewriting the lines annoyed some producers, who crossed Hope off their guest lists as a result.)

Hope once asked one of his writers, Bob Mills, for jokes about Pentagon generals even though he had no scheduled appearances before military audiences. When Mills asked why, Hope explained that he needed the scripted lines to make conversation with three generals he was meeting for a round of golf.

Zoglin peppers his biography with swaths of Hope material—jokes, movie dialogue, his patriotic perorations—as if they might give us some insight into the man himself. But it’s hard to attribute these passages to him or read them as revelatory since we know they were all written by Norman Panama, Melvin Frank, Sherwood Schwartz, Larry Gelbart, or any of the other top-tier comedy writers who cycled through the Hope word factory. Take away the writers’ contributions to “Bob Hope” and what do we know of the offstage Bob Hope?

Zoglin gleans what little he can. Clearly the straitened circumstances of Hope’s childhood left him with a zeal for financial success and security, which he achieved with hard work, his tough show business deal-making, and shrewd investments in oil and California real estate. Hope’s other principal compulsion was his addiction to adulation from strangers, whether the throngs he entertained on the road, his studio audiences (who were kept unusually close to the stage in a Hope-designed configuration of stacked rows), or the interchangeable sexual partners that he procured into his eighties.

But there’s no evidence that he enjoyed emotional intimacy with anyone. He was as much an absentee father to his four adopted children as he was an absentee husband. He and Crosby were not close; Hope’s writers were regularly demeaned and cashiered. Despite their shared Hollywood history and conservative Republicanism, Hope was not, as one might assume, a pal of the Reagans.

“Even to intimates and people who worked with him for years, he remained largely a cipher,” Zoglin writes. “He never read books or went to art museums, unless he was dedicating the building.” A Time reporter who trailed Hope for an article in 1963 concluded “there just wasn’t much there”; Hope was cooperative and gracious but “flat, faceless, withdrawn” when he wasn’t tossing off jokes. Johnny Carson, the other big comedy star on NBC, concurred. Superficially he and Hope had much in common. As Zoglin writes, Carson was also “cool, remote, and emotionally detached, ingratiating on the surface, but known intimately by only a few.” And he, too, relied heavily on writers for his brilliantly delivered monologues. But Carson “was not a great admirer” of Hope’s work, according to his longtime producer Peter Lassally, and did not regard Hope as a good guest. Andrew Nicholls, a former Carson co–head writer, elaborated to Zoglin:

There was nothing spontaneous about Hope. He was a guy who relied on his writers for every topic. Johnny was very quick on his feet. Very well read. He was a guy who learned Swahili, learned Russian, learned astronomy. He appreciated people who he felt engaged with the real world. There was nothing to talk to Bob about.

Hope’s only known hobby was golf. He didn’t much engage even with the political causes he supported. “Bob never really understood the public thinking on Vietnam,” said his long-time writer Melville Shavelson, “because he rarely discussed the war with anyone below a five-star general.” Though Hope was a staunch anti- Communist who approved of Joe McCarthy, his jokes on the subject were generic and passionless: “Senator McCarthy is going to disclose the name of two million Communists. He just got his hands on a Moscow telephone book.” The milquetoast quality of Hope’s “topical” jokes and occasional political remarks suggests that he didn’t read the papers much beyond the gossip columnists Walter Winchell (whose film biography was a perennial unrealized Hope project) and Hedda Hopper (who accompanied him on some of his Christmas tours of military bases).

In trying to answer the question of why Hope is in eclipse today, Zoglin speculates in part that he “never recovered from the Vietnam years.” Hope made a spectacle of himself then, not so much in his knee-jerk support for the war (his hawkishness did not diminish his Nielsen ratings) but in his obliviousness to the rapid changes in pop culture going on all around him. Ed Sullivan was a bit older than Hope and is no one’s idea of a hipster, but he figured out that the Beatles were more than a passing fad, not to mention a commercial opportunity, and booked them at first sight on his own televised vaudeville show. Hope dismissed them with a tone-deaf gag: “Aren’t they something? They sound like Hermione Gingold getting mugged.” A particularly painful sight among the photos in Hope is a shot of the middle-aged Hope, Steve Lawrence, and Eydie Gormé draped in wigs and beads to satirize unwashed hippies. The sharpest insult Hope could muster about Woodstock was that it produced “the most dandruff that was ever in one place.”

In truth, Hope’s brand of comedy was dated before Vietnam consumed the 1960s. New comics like Mike Nichols and Elaine May, Woody Allen, Richard Pryor, Shelley Berman, Bill Cosby, and Bob Newhart all emerged earlier in the decade, just ahead of the counterculture, and quickly became mainstream figures. Unlike their immediate predecessor, Lenny Bruce, they were routinely booked on prime-time television (especially The Ed Sullivan Show) and had hit comedy records. Like Hope, they rarely touched on politics in those days, but unlike him, they had idiosyncratic voices—and in most cases developed or wrote their own material.

A half-century later, in our current boom market for comedy, the most popular comedians in America, whether on television or not, are direct descendants of that first new wave of early 1960s comedians. Except for the now semiretired Jay Leno and perhaps his successor on The Tonight Show, Jimmy Fallon, it would be hard to name a major American comic of the twenty-first century who is in the Hope mold.

The impersonality of his jokes and the evanescence of his topical references make his television monologues seem more ancient than they actually are. It’s hard for comedy to retain its freshness when it surrounds a human vacuum. A monologue from Hope’s early 1960s television heyday yields few laughs compared to other stand-up routines of the same vintage that are cheek-by-jowl on YouTube. But there is something about the whole Hope package that is arresting even so: a tightly disciplined musical gift for rhythmic verbal stylization, a cocky physical posture, an almost demonic will to entertain that is, as Zoglin writes, “an affirmation of the American spirit: feisty, independent, indomitable.” A Hope performance is as precise and ritualistic as Kabuki, really, and mesmerizing right up to the point that you find yourself tuning out the words.