It’s not often that a biographer is as fortunate with his subject as Ian S. MacNiven has been with James Laughlin. As the founder and publisher of New Directions, the most prominent press in this country of modernist American and foreign literature, Laughlin not only had an interesting life, or more accurately several lives that he somehow managed to lead concurrently, he also exchanged thousands of letters with writers he published, friends, and family members, thus leaving behind an astounding amount of material for his future biographer.

His story and the story of the company he ran for over fifty years as well as the history of modernism in this country are so intertwined that they cannot be told separately. It is worth recalling that avant-garde writing in the 1930s, when he started his press, was either totally unknown or regarded as a joke. I don’t believe Laughlin ever thought of himself as a missionary, but he ended by influencing what generations of educated Americans read and what poetry and fiction were taught in schools.

Fifty years ago, when libraries on army posts in the United States and overseas were often as well stocked as small-town libraries, I came across a large collection of New Directions books in Toul, France, and over a period of fifteen months I got myself an education in modern literature no college course could equal. I’d lie on my bunk in the barracks reading Céline, Sartre, Nabokov, Djuna Barnes, Pound, and Williams late into the night, while my buddies played cards and listened to their radios. I may have been just a lowly private, but unknown to anyone else there, with the sole exception of a Frenchwoman who was the post librarian, I was in heaven.

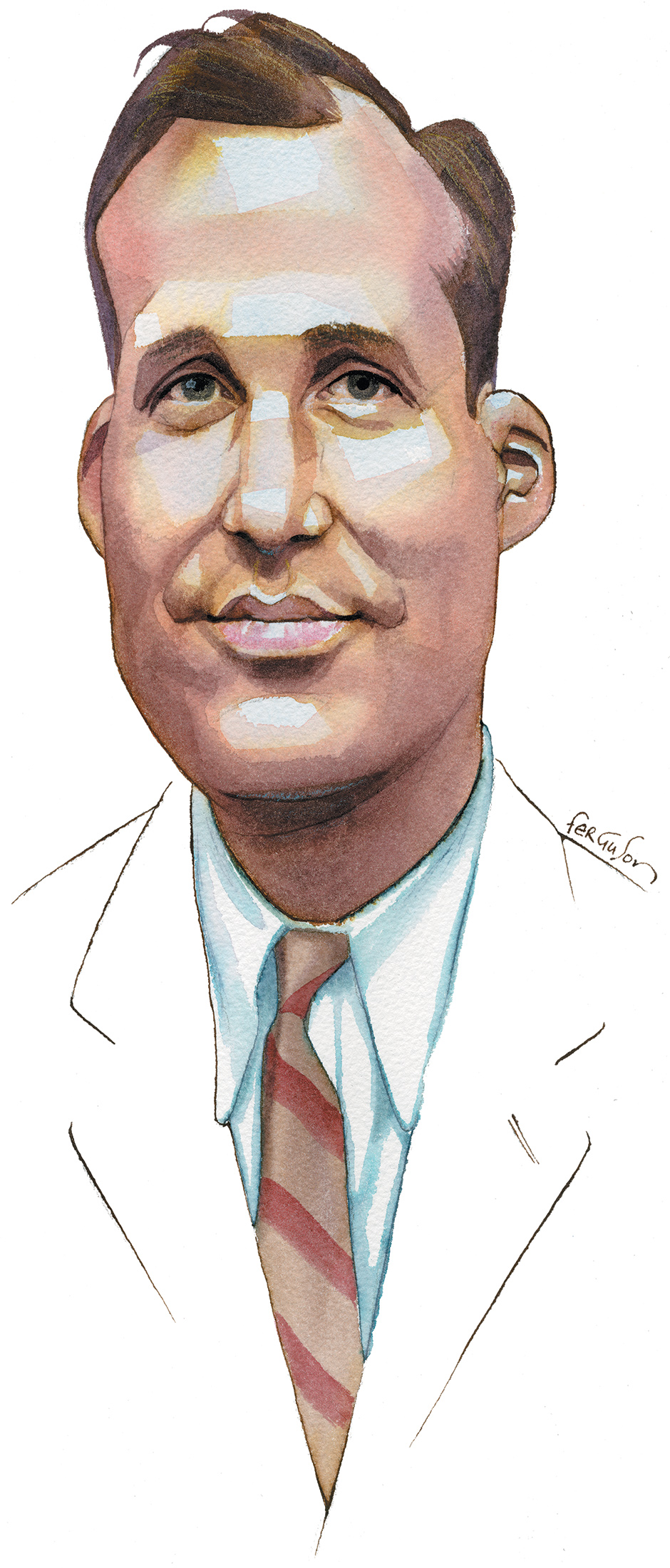

James Laughlin was born in 1914 in Pittsburgh, into a wealthy family in the steel business. The Jones & Laughlin Steel Corporation had been founded three generations earlier in 1856 by his great-grandfather, who with his partner made a fortune during the Civil War as the main producers of iron rails. By 1900 they were the second-largest steel producer in the United States. Andrew Carnegie and the Mellons lived down the street from them. Laughlin “would later characterize his birthplace as tough-minded, practical, and philistine,” recalling how after the coffee a butler would pass around chewing gum on a silver tray.

There was a lot of Bible reading and catechism, but no deep religious feelings. He once asked an uncle what the sacred studies were and the uncle replied that he wasn’t really sure, but guessed they came in a bottle. Laughlin’s mother attended the Presbyterian Church and was one of its benefactors, but his father, who had resigned his position in the company and held no job, left religion alone, spending Sundays boating, hunting, or going to the races and the rest of the week diverting himself with long-hooded cars and women.

His son was an insecure child well cared for by servants. His interest in literature didn’t develop until he was exposed to French poetry in boarding school at Le Rosey in Switzerland and subsequently at Choate in Connecticut, which he started attending at fourteen and where one of his teachers, Dudley Fitts, made him read the classics and modernists and later provided him with introductions to Gertrude Stein and Ezra Pound. His parenting, by the time he had moved east to attend school, was taken up by an aunt and uncle living in Norfolk, Connecticut. What he retained from his upbringing was a social conscience that placed wealth second in importance to service and left him with residual guilt for being rich. Jones & Laughlin had a reputation as the toughest anti-union company in America, so it is worth noting that in his forties Laughlin divested himself of whatever holdings he had in the steel business.

Harvard University, where Laughlin matriculated in 1932, was an aloof and cliquish place in comparison to Choate. Nonetheless, he got close to a few professors, most importantly to Harry Levin, a scholar of enormous learning in many literatures and subsequent author of James Joyce: A Critical Introduction, which New Directions published in 1941. One would think that such a brilliant circle of acquaintances would have made him content, but to everyone’s surprise, he went to Europe after his freshman year.

After a short stay in Austria, he wrote a brash letter to Pound in Rapallo, asking whether he would care to see him and telling him that he was an American “said to be clever” and known to Fitts, who wanted “elucidation” of certain basic aspects of the Cantos so that he may be able to “preach” them intelligently to others. Finally he boasted that as an editor of The Harvard Advocate and Yale’s Harkness Hoot, he had access to “the few men in the two universities” who were “worth bothering about.” Pound replied promptly and invited him to visit, and upon meeting Laughlin gave him the names and addresses of people like William Carlos Williams and others he wanted the young man to see when he returned to the States.

Advertisement

Back at Harvard, Laughlin became the recipient of Pound’s jocular letters addressed to “Dilectus Filius” in Pound’s peculiar lingo, delivering sweeping judgments of everything from American education—“No prof. expected to know anything he wasn’t TAUGHT when a student”—to politics—“F.D.[R.] has gone communist but New Masses will never find it out.” When Laughlin said some disparaging things about T.S. Eliot, Pound rushed to the defense of his old friend, saying: “When Joyce and Wyndham L. have long since gaga’d or exploded, Old Possum will be totin’ round de golf links and givin’ bright nickels to the lads of 1987.”

Laughlin took a leave of absence from Harvard the following year and returned to Europe. He stayed with Gertrude Stein and Alice B. Toklas in their country place in Bilignin for a month and accompanied them on a motoring tour of southern France. He found Stein to be the most charismatic person he’d ever met and admired her artistic integrity, but grew weary of her boasting. Once she caught him reading Proust and demanded angrily how he could read such stuff. Didn’t he know, she said, that both Joyce and Proust imitated her novel The Making of Americans?

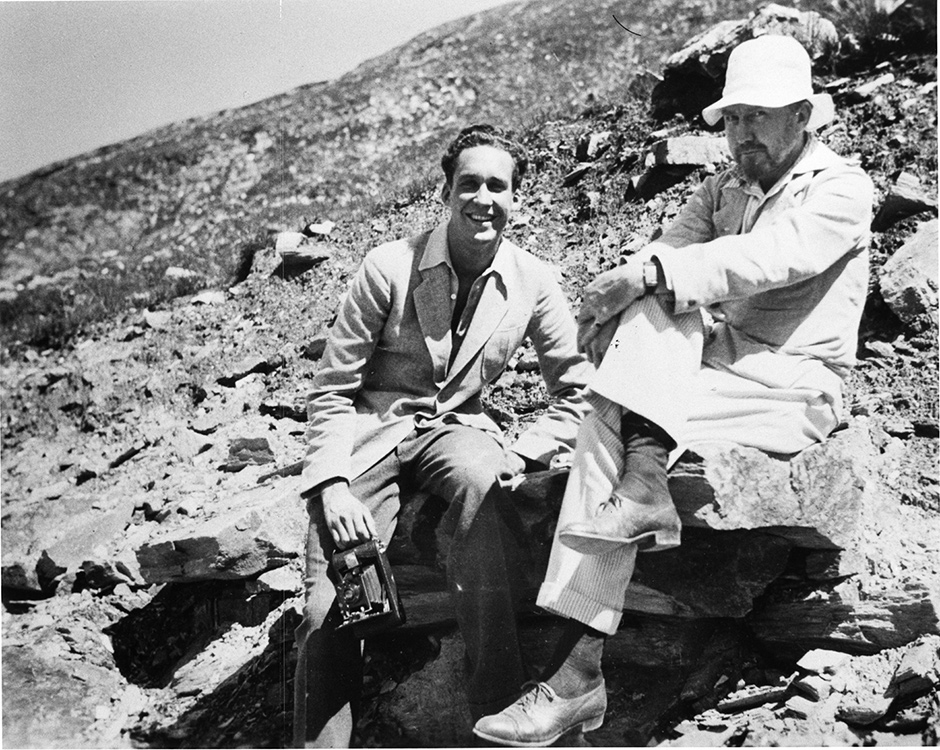

After his visit with her, Laughlin continued to Rapallo to take up his “studies” in the “Ezuversity,” a marvelous educational institution with no tuition, where classes consisted of Pound’s nonstop monologue as he ate his meals, played tennis, and went swimming and hiking. “Literachoor is news that stays news,” he told him. Laughlin, who came to know many epic talkers in his life, “invariably held up Pound as the standard against whom all other talkers were to be measured,” MacNiven writes.

It was partly his delivery, his form of Appalachian cracker-barrel mixed with English upper-class and Cockney accents, done in mockery, alternating with black American slang via Uncle Remus, all salted with profanity and peppered with words and phrases in many European tongues.

No wonder Laughlin stayed for several months. Occasionally, Pound took a look at his poems, slashing with a pencil words and entire pages and telling him to simplify, pare it down, and make it new. As MacNiven notes, Laughlin found in Pound not a replacement for his own father, but an intellectual father, a soul’s father. Nonetheless, even at that young age, he saw his mentor clearly as both vain and humble, patient and rash, clear-sighted yet prejudiced; a genius in some ways, a simpleton in others. Pound complained about the difficulties writers like him and Williams had in finding good publishers in the United States. Writing to Williams, he told him that his pupil wanted to stay in Rapallo, but that he urged him to return to the US and try to see if anything could be done in that sloppy country. “I went to him with fairly conventional views about almost everything,” Laughlin says in his Paris Review interview, “and I left him with either very eccentric or radical views about everything—views which have persisted with me to the present day.”

Well, not quite everything. Laughlin became embroiled with Pound about his fascist sympathies and his anti-Semitism almost from the beginning of their long relationship. Pound kept denying that he was anti-Semitic, insisting that he was only against big usurers and monopolists and not the working-class Jews. “My connection with Pound always lays me open to attacks of being a Fascist,” Laughlin complained to Delmore Schwartz, “and that is not very pleasant.” He would remain a convert to Pound’s economic theories, while loathing his racist theories and his politics. He made that clear to him in a letter he wrote on December 5, 1939:

I think anti-semitism is contemptible and despicable and I will not put my hand to it. I cannot tell you how it grieves me to see you taking up with it. It is vicious and mean. I do not for one minute believe that it is solely the Jews who are responsible for the maintenance of the unjust money systems. They may have their part in it, but it is just as much, and more, the work of Anglo-Saxons and celts and goths and what have you.

Laughlin began his career in publishing as the literary editor of New Democracy, a magazine devoted to the economic theory of Social Credit, where he published Pound, Stein, and Williams in a section of the magazine entitled “New Directions.” As Robert Lowell recalled years later, “our only strong and avant-garde man [at Harvard] was James Laughlin.” Upon his return to the university, he gathered the best of these pieces and put them together in an anthology called New Directions in Prose and Poetry. The impressive table of contents included Williams, Pound, Elizabeth Bishop, Henry Miller, Marianne Moore, Wallace Stevens, Kay Boyle, Jean Cocteau, E.E. Cummings, and others now less known.

Advertisement

Laughlin initially ran his fledgling publishing company from his dorm room, and after that, from a barn converted into an office on his Aunt Leila’s estate in Norfolk, Connecticut. In a brochure sent to librarians at the time, he spoke of the need for a publishing house concentrating on books of purely literary rather than commercial value. In MacNiven’s summary, “to achieve financial rewards, ‘the average publisher’ must perforce cater to the ‘poor taste of the masses.’ New Directions would cater to ‘the cultivated taste of educated readers.’” The number of such readers being few, he managed to stay afloat while publishing money-losing books thanks to a nice chunk of money from his father and an additional one from his family until the press finally turned a profit in 1947.

Founded with the encouragement of Pound, his company relied on the advice of writers with whom Laughlin was friendly. Eliot introduced Djuna Barnes; Pound, William Carlos Williams; Williams, Nathanael West; Edith Sitwell, Dylan Thomas; Henry Miller, Hermann Hesse, though many of these unofficial advisers could be as fervent in their hatreds as in their enthusiasm.

Delmore Schwartz, for instance, advised him to publish Pound’s collected essays, publish Pasternak and Nabokov, reprint Dylan Thomas, make every effort to keep Williams, and disastrously to reject F. Scott Fitzgerald’s The Crack-Up. Kenneth Rexroth, who would become one of his most frequently published authors with twenty-eight books, had a low opinion of Schwartz’s poetry, asking Laughlin: “Is it really true that you plan to publish nothing but the Complete Delmore Schwartz from here on?” Edward Dahlberg, another one of his authors, complained that his list leaned “too much toward preciosity,…experimentalism, dadaism, gagaism…. Publish six or seven or ten artists, follow them through, and you can create a lasting literature,” he told him. “This publishing philosophy,” as MacNiven says, “was exactly the direction in which” Laughlin himself was already moving.

His most important contribution may have been in bringing foreign writers to American readers. The list includes Baudelaire, Rimbaud, Rilke, Valéry, Kafka, Montale, Neruda, Queneau, Lorca, Paz, Borges, Mishima, Svevo, Landolfi, Céline, Gide, Apollinaire, Cendrars, and Hesse’s Siddhartha, which became a best seller. Pound and Williams, however, were the backbone of the press, followed in later years by Henry Miller, Tennessee Williams, and Thomas Merton.

“For better or worse,” Laughlin once said about the press, “there has been no editorial pattern beyond the publisher’s inclinations, his personal response to the manuscripts which came his way.” He chickened out when he had a chance to publish Nabokov’s Lolita, but brought out other unconventional and shocking books that would have appalled his family had they bothered to read them. When his mother did, she sent her chauffeur to the bookstores in Pittsburgh to buy up copies of the anthology New Directions in Prose and Poetry 1939, which included selections from Henry Miller’s Tropic of Capricorn.

The biggest complaint Laughlin’s authors had about their publisher, aside from miserable advances and small royalty checks, is that he used to absent himself for months to go skiing in this country and Europe and could not be reached. For example, after publishing William Carlos Williams’s novel White Mule in 1937, he left to go skiing in New Zealand. When bookstores sought additional copies of the novel, he was not around to get more bound, infuriating Williams, who nursed a grudge against him for years. He wasn’t the only one. Many others griped, and some like Rexroth wrote nasty letters heaping contempt on him, even though in some cases he paid his writers’ rent and bailed them out of jail. Despite the insults, Laughlin’s faith in their genius never wavered. His defense was that most of the time New Directions lost money, so that he was obliged to keep the losses to a minimum, and that their own books didn’t sell well.

As for skiing, he couldn’t help himself. He said that he went to Harvard rather than Princeton because it was closer to ski slopes in New Hampshire and Vermont. Despite falling and breaking his back in 1936, he continued skiing and later founded with some ski buddies the Alta Ski Area in Utah, which after World War II, when alpine skiing became popular, brought enormous returns on his original investment. Years later he admitted that he could have been more attentive to his writers had he been less absent from the office, but skiing meant a lot to him and was in addition an opportunity to make some money to support his publishing venture, so that he wouldn’t have to go begging to his relatives.

Whatever the truth of the often-repeated tale that Pound took one look at Laughlin’s poems in Rapallo and told him to forget poetry and go home and become a publisher, which MacNiven doubts, the advice didn’t stick. Laughlin wrote poems all his life and had five small books published by little-known presses, which he gave away mostly to his friends, some of whom, like Williams and Rexroth, praised the poems and meant it. However, once he was in his sixties and became more sedentary after a life of travel, he became astonishingly prolific, often writing three to four poems per day, so that more than three quarters of some 1,250 poems in the recent edition of his collected poems were written in the last fifteen years of his life. Even then, he didn’t make any effort to promote himself, claiming, when someone inquired about his poems, that he was a writer of light verse.

“Anything is good material for poetry,” Williams had said and Laughlin believed that too. Make it so simple that a child of six can understand the words (if not the sense), then take out all the words that aren’t doing anything useful, Pound had advised him. Nevertheless it was Williams’s free verse rather than Pound’s that influenced him.

To write his poems, Laughlin would type out a line of a poem and then make sure the length of the following line was within two typewriter spaces of the line preceding it, and go on from there. He called it “typewriter metric,” a mechanical space count in which the spaces between words counted equally with letters. Here’s how that kind of poem looks and sounds:

THE CAVE

Leaning over me her hair

makes a cave around herface a darkness where her

eyes are hardly seen shetells me she is a cat she

says she hates me becauseI make her show her pleas-

ure she makes a cat-hatesound and then ever so

tenderly hands under myhead raises my mouth into

the dark cave of her love.

Knowing several languages, being a lifelong reader of classics and an editor and a publisher familiar with not just American but many other literatures in the world, Laughlin was prodigiously learned. Pound made him a multiculturalist. He inherited his old teacher’s belief that the poets of the past are our contemporaries. “Catullus could rub words so hard/together their friction burned a/heat that warms//us now 2000 years away.” Pound was Laughlin’s master. Juxtaposing American life and spoken language with voices of the past was his forte as much as it was Pound’s. He wrote short lyric poems, long-line poems, prose poems, concrete poems, poems written entirely or in part in French or mixed with German, Greek, Italian, Latin, Provençal, and also humorous poems under the name of Hiram Handspring.

They vary greatly in subject matter. There is, for example, a lovely poem about meeting Baudelaire on the New York subway in the company of a light-skinned black girl. There is also an excruciating poem called “Experience of Blood” about the suicide of his son, who stabbed himself repeatedly in the bath. Laughlin describes how it took him four hours to wipe away the blood. In an early book, he published a poem about the greed and callousness of American businessmen during the Great Depression:

CONFIDENTIAL REPORT

The president of the

corporation was of theopinion that the best

thing to do was justto let the old ship

sink as pleasantly &easily as possible be-

cause it was plain asday you couldn’t op-

erate at a profit aslong as that man was

in the white house &now he was there for

good you might justas well fold yr hands

and shut yr face andlet the old boat take

water till she sank.

If Laughlin is remembered as a poet—and I very much hope he will be, since he wrote many beautiful poems—it will be for his erotic poems. He wrote hundreds of them, many of them in his old age. They were about women he was in love with over the years, recalling what it was like being with them. With three marriages and more illicit affairs than even his biographer can keep track of, it is impossible to know to whom the poems are addressed, though it is clear that they are addressed to particular women and not some generic idea of the loved one. Love poems are notoriously difficult to write, since the vocabulary relating to love and lovemaking is so limited and one’s attraction to another human being is so difficult to convey beyond stock attitudes and hackneyed phrases, some of which have been in use by poets for over two thousand years.

Inevitably for someone so prolific, Laughlin wrote mediocre and forgettable poems, but not too many that are downright bad; because he was a cultivated, complex man with a life so full of memorable experiences, nearly everything he wrote is worth reading at least once. The surprise of the huge book of his collected poetry is not just how many of the poems he wrote are good, but that most readers of poetry don’t even realize they exist. Here, for example, is a poem written in his old age about death that is both grim and funny and that, I must confess, has haunted me since I first read it years ago while Laughlin was still alive:

THE JUNK COLLECTOR

what bothers me most about

the idea of having to die(sooner or later) is that

the collection of junk Ihave made in my head will

presumably be dissipatednot that there isn’t more

and better junk in otherheads & always will be but

I have become so fond ofmy own head’s collection.

James Laughlin died in 1997 in Norfolk, Connecticut, at the age of eighty-three, from complications related to a stroke. I strongly hope that the simultaneous publication of his collected poems and of the hugely entertaining biography by MacNiven will not only perpetuate the memory of this extraordinary man and his poetry, but also renew interest in one of the richest periods in American literature. What makes any biography worth reading is not solely the interesting life of some famous or not-so-famous person, but the stories in it worth remembering and retelling. With so many fascinating and outrageous characters, many of whom turned out to be the biggest names in literature, there is a small encyclopedia of literary anecdotes in MacNiven’s book, not counting the picaresque adventures of its tall, handsome hero who knew everybody and whom the ladies found irresistible, and who, as we come to learn, did all that astounding amount of reading, writing, skiing, and womanizing with just one functioning eye in his head.