During the past fifty years, most of the debate on the Catholic Church’s relationship with fascism has focused on the wartime period and the Vatican’s response to the Holocaust. Did the virtual silence of Pius XII, who became pope in early 1939, about the mistreatment and extermination of Europe’s Jews facilitate Hitler’s Final Solution, as his critics insist, or was it, as Pius’s defenders maintain, a heroic act of self-discipline that prevented Nazi reprisals against the many thousands of Catholic institutions that were secretly hiding and helping Jews? The debate, as Pius XII inches his way toward sainthood, has become somewhat sterile since it depends partly on difficult-to-prove arguments about what might have happened had he spoken out.

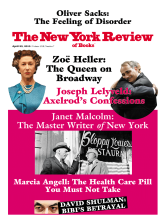

One of the many virtues of David Kertzer’s The Pope and Mussolini is that it reframes the discussion by shifting attention away from World War II and looking closely at the papacy of Pius XII’s predecessor, Pius XI, who became pope in 1922, the year that Benito Mussolini came to power, and died in early 1939, several months before Hitler invaded Poland. Taking advantage of the gradual opening of Vatican archives, Kertzer offers us a much more detailed portrait of the inner workings of the Vatican in this period. The many revelatory incidents, documents, and scenes he adds to the story are bound to reanimate the older debate on Pius XII.

When Mussolini seized power in his so-called March on Rome in October 1922, Achille Ratti, a scholarly librarian and former archbishop of Milan, had only recently become Pope Pius XI. The Catholic Church had not been particularly supportive of fascism during its rise. Mussolini, after all, had started out his career as an outspoken atheist and anticlerical firebrand. The Church supported its own specifically Catholic party, the Partito Popolare, or Popular Party, which competed with both the Socialists and the Fascists.

To the pope’s surprise, on taking power Mussolini immediately began a concerted campaign to win the Church’s support. He used his first speech to Parliament to articulate his vision of a Fascist society that placed the Church at the center of Italian life: the Fascist Party would be the unquestioned authority in political life and the Church would be restored to its primacy over the spiritual life of the nation. Mussolini followed up his speech with a series of concrete actions: crucifixes were placed in every public school classroom, courtroom, and hospital room; insulting a priest or disparaging the Catholic religion was made a criminal offense; Catholicism became a required subject in public schools; and considerable state funds were spent on priests’ salaries, as well as Church-run schools overseas.

This represented a remarkable departure—not just for Mussolini but for Italy. The battle to create a united Italian state had been fought, in part, at the expense of Church power, and resulted in the end of the pope’s temporal rule over Rome and much of central Italy. It took the popes decades to realize that Italy was a permanent reality that they needed to accept. Mussolini offered them the possibility of doing so on highly favorable terms. Almost immediately he began secret negotiations for a treaty between the Vatican and the Italian state. This concordat, known as the Lateran Treaty, was signed in 1929; it made Catholicism Italy’s state religion and compensated the Church for its lost territories with a generous financial settlement. Pius XI was so pleased with the treaty that he referred to Mussolini as the “man sent by providence.”

The general outlines of this story have always been matters of public record, but Kertzer’s book deepens and alters our understanding considerably. The portrait that emerges from it suggests a much more organic and symbiotic relationship between the Church and fascism. Rather than seeing the Church as having passively accepted fascism as a fait accompli, Kertzer sees it as having provided fundamental support to Mussolini in his consolidation of power and the establishment of dictatorship in Italy.

The Vatican’s first and perhaps most important contribution was the dismantling of the Popular Party, which in the first years of fascism remained one of the greatest obstacles to dictatorial rule. As Mussolini began to negotiate the Lateran Treaty, he made it clear that he considered it an intolerable contradiction for the Church to enter into a partnership with his regime while at the same time fielding an opposition party that criticized it. Just eight months after the March on Rome, Pius XI forced Father Luigi Sturzo, the founder of the Popular Party, to resign as party secretary.

Kertzer writes that Pius XI may have had a crucial part in supporting Mussolini at a moment when he might well have fallen from power. In 1924, Italy held elections that were badly marred by violence, intimidation, and fraud. Not surprisingly, the Fascists obtained a majority, but the Popular Party and the Socialists, braving impossible conditions, held on to significant minorities. When the Socialist deputy Giacomo Matteotti denounced the conduct and outcome of the elections, he was kidnapped and murdered in downtown Rome. The Matteotti killing shocked the Italian middle and upper-middle classes, who suddenly began to rethink their support of fascism. As the investigation unfolded, the opposition suddenly regained vigor. Mussolini went into a kind of personal crisis, seeming to regard his own resignation as inevitable. Even pillars of the Italian establishment like the Milan newspaper Corriere della Sera now called on him to step down. What was left of the Popular Party, the Catholic party, was also calling for a new government. This would almost certainly have required a coalition between the Catholics and the Socialists.

Advertisement

The Vatican, instead, decided to support Mussolini. An internal political briefing from this period stated:

Catholics could only think with terror of what might happen in Italy if the Honorable Mussolini’s government were to fall perhaps to an insurrection by subversive forces and so they have every interest in supporting it.

Pius XI, through his personal emissary, Father Pietro Tacchi Venturi, sent Mussolini a private message of encouragement and solidarity. On a more concrete level, the pope also silenced Father Sturzo, who although no longer the head of the Popular Party remained a prominent public figure denouncing fascism. Sturzo was ordered to stop publishing his views and reluctantly agreed to leave Italy.

Without a unified opposition, the crisis passed and Mussolini regained his footing. “If Mussolini was not deposed as a result of the Matteotti crisis,” Kertzer writes,

it was because the opposition—not least due to the pope’s constant efforts to undermine any possible alliance to put an end to Fascist rule—failed to offer a credible alternative. Lacking this alternative, neither the king nor the army was willing to act.

In 1926, all opposition parties were forced to dissolve, including, of course, the Popular Party, which the pope accepted without difficulty. As Father Sturzo wrote in protest, the pope was getting rid of the one party “that is truly inspired by Christian principles of civil life and…today serves to limit…the arbitrary rule of the dictatorship.”

It is perhaps surprising to some today that the pope would not have been more concerned about killing off Italy’s Catholic party and its democracy as well. But for the Vatican, democracy was hardly a positive value and it had only reluctantly allowed the creation of the Popular Party in 1919. After all, the movement toward parliamentary democracy in modern Europe had gone hand in hand with a series of other movements calling for reforms that would break the Church’s power in much of European society: freedom of speech, individual rights, separation of church and state, public secular education, the confiscation of Church lands, and equal rights for other religions or even those who held no faith at all.

With the Lateran pact, both the Vatican and the Fascist regime saw themselves as having entered into a form of partnership. The Vatican turned to Mussolini to ban books the Church found offensive and to prevent Protestants from trying to spread their faith. In return, Mussolini expected the Church to support the dictatorship. Having done away with opposition political parties, fascism would instead hold public referendums in which voters were asked to vote yes for the regime and for a preselected slate of candidates for Parliament. Before the first referendum in 1929, the pope, as Kertzer shows, insisted on vetting the potential candidates, rejected some three quarters of them as insufficiently Catholic, and demanded a new list that was “free from any tie with Freemasonry, with Judaism and, in short, with any of the anticlerical parties.”

The pope considered this extraordinary request a fulfillment of the Lateran Treaty. As a Vatican letter to Mussolini explained:

In this way the Duce will place…the most beautiful and necessary crown atop the great work of the treaty and the concordat. He will show one more time that he is (in conformity with what His Holiness recently called him) the Man sent by Providence.

When the regime complied, Italy’s priests literally led their congregations to the ballot boxes.

It is shocking to see the Vatican insisting on the exclusion of Jews from political life nearly ten years before the Fascist regime introduced anti-Semitic legislation, in 1938. In what are likely to be the most controversial parts of Kertzer’s book, he shows that some elements of the Vatican were urging fascism toward anti-Semitism well in advance of its own decision to make a public issue of race. The Jesuit father Pietro Tacchi Venturi, Pius XI’s emissary to Mussolini, a man who thus had the ear of both the pope and the dictator, was a rabid anti-Semite who appears to have firmly believed that “the worldwide Jewish-Masonic plutocracy” was the Church’s greatest enemy. As Kertzer writes:

Advertisement

In September 1926 Tacchi Venturi gave the Duce a recently published fifteen-page pamphlet, Zionism and Catholicism, which had been dedicated to the Jesuit himself. The pamphlet, after recalling that God condemned the Jews to wander the earth and cursed them for rejecting Jesus, turned to the more immediate dangers the Jews posed. “No one can doubt,” its author warned, “the Jewish sect’s formidable, diabolical, fatal activity throughout the world.”

There is no indication that the Duce paid much attention to the pamphlet or that it reflected the views of the pope. But Tacchi Venturi made no secret of his views, and they obviously didn’t diminish his standing as one of the pope’s most trusted advisers. Belief in the Jewish conspiracy was a widely held and entirely respectable position in the Catholic Church of the 1920s and 1930s. On reading Kertzer’s book, one would have to say that some form of anti-Semitism—the tendency to regard Jews as a troublesome minority fundamentally hostile to the Church—was the norm at the highest levels of the Vatican in the 1930s.

The intensity of this belief varied considerably, moving along a spectrum from mild to virulent anti-Semitism. Pius XI was on the milder end. He recalled with fondness his days in Milan when he received Hebrew lessons from a local rabbi to help him with his Bible studies. He regarded anti-Semitic legislation in Italy, where Jews were a mere one in a thousand of the population, as unnecessary, but he accepted that some countries where Jews were far more numerous might need to take measures to avoid Jewish “dominance.” When he was papal nuncio to Poland, he warned that much of the disorder that followed World War I was the result of the Poles falling

into the clutches of the evil influences that are laying a trap for them and threatening them…. One of the most evil and strongest influences that is felt here, perhaps the strongest and the most evil, is that of the Jews.

In 1928, Pius XI endorsed the decision of the Vatican’s Holy Office (the successor to the Inquisition) to suppress the Catholic organization called the Friends of Israel. Although devoted to the eventual goal of converting the Jews, the group called for the Church to treat the Jews with greater respect and sympathy. Its members included thousands of priests, 278 bishops, and nineteen cardinals.

The group evidently went too far when it called on the Church to abandon the tradition of referring to Jews as Christ-killers and to give up the traditional Easter prayer referring to the “perfidious Jews.” Cardinal Rafael Merry del Val, the head of the Holy Office, a former Vatican secretary of state and one of the most powerful cardinals in Rome, insisted that the Friends of Israel had been unwitting tools of the Jews’ plan to “penetrate everywhere in modern society…to reconstitute the reign of Israel in opposition to the Christ and his Church.” After meeting with Pius XI, Merry del Val reported that the pope shared his view that “behind the Friends of Israel one finds the hand and the inspiration of the Jews themselves.”

One of the most valuable achievements of Kertzer’s book is that it creates an institutional portrait of the Vatican. While it deepens our understanding of individual historical figures—Pius XI, but also his secretary of state, Eugenio Pacelli, who became Pius XII—it shows extremely well that even in an autocratic organization like the Vatican, the pope does not always act alone. There is a permanent bureaucracy with deep institutional biases and tendencies that can often shape and mold papal action.

Kertzer’s evidence makes it clear that it became almost irrelevant whether Pius XI was or wasn’t anti-Semitic or pro-fascist. He was surrounded by a powerful group at the Vatican who shared authoritarian, antidemocratic political views and whose thought was deeply permeated—to varying degrees—by anti-Semitism.

Perhaps the most dramatic account in The Pope and Mussolini is the story of how, during the last years of Pius XI’s papacy, he apparently underwent a transformation: he soured on fascism and became disillusioned with Mussolini and disgusted by Hitler. Unlike his principal advisers, he seems to have gradually understood that fascism was not just another conservative movement but a dangerous pagan ideology that was deeply at odds with Christianity. “Tell Signor Mussolini in my name,” the pope told the Italian ambassador to the Holy See in 1932, “that I do not like his attempts at trying to become a quasi- divinity and it is not doing him any good either…. Sooner or later people end up smashing their idols.”

During these years the Vatican bureaucracy worked hard to suppress, weaken, water down, or quash virtually all the pope’s criticism of Mussolini or Hitler in order to smooth over or avoid diplomatic conflict. In 1935, when Italy invaded Ethiopia, Pius XI denounced it as an “unjust war,” “unspeakably horrible” in front of a group of religious nurses who had come for a papal audience.

In Rome, the curia set about adulterating the pope’s remarks so as to obfuscate their real meaning when they appeared in L’Osservatore romano. “Here I cut a word, there I add another,” recalled Domenico Tardini, a high-level official in the Vatican secretary of state’s office, noted proudly in his diary. “Here I modify a sentence, there I erase another. In short, with a subtle and methodical effort we succeed in greatly softening the rawness of the papal thought.”

Similarly, when America, an influential Jesuit magazine in the US, published a strong criticism of Italy’s war in Ethiopia, the Italian government went behind the pope’s back by protesting to Włodzimierz Ledóchowski, the general superior of the Jesuit Order, a man known for his pro-fascist leanings and virulent anti-Semitism. Ledóchowski obliged by replacing America’s anti-fascist editor with one who supported the regime.

Pius XI was mortified that Mussolini invited Hitler to Rome in May 1938 and turned the entire city into a welcoming platform for the author of Mein Kampf, plastering the city of the popes with swastikas. Pius, in a very clear gesture, left Rome during Hitler’s visit and closed the Vatican Museums, preferring to avoid what he called “the apotheosis of Signor Hitler, the greatest enemy that Christ and the Church have had in modern times.”

And when, during the summer of 1938, it became clear that Mussolini was ready to follow Hitler in adopting an official policy of biological anti-Semitism, the pope was scathing. He told a group of students about the dangers of “exaggerated nationalism,” insisting on the essential unity of the human race and lamenting Mussolini’s aping of Hitler. “One can ask how it is that Italy, unfortunately, felt the need to go and imitate Germany.”

Terrified by the prospect of a major public condemnation of Mussolini’s new racial policy, the regime asked for the help of Father Ledóchowski, who as head of the Jesuits was one of the most powerful figures in the Church. “I went to see the general of the Jesuits,” Italian ambassador Pignatti later explained, “because in the past…he did not hide from me his implacable loathing for the Jews, whom he believes are the origin of all the ills that afflict Europe.”

Ledóchowski described in letters what he regarded as the feelings of desperation within the Vatican. The closest advisers of Pope Pius XI, he wrote, had come to regard him as in dangerous decline, making ill-advised remarks without consulting them. “Cardinal Pacelli was at his wit’s end: ‘The pope no longer listens to him as he once did. He carefully hides his plans from him and does not tell him about the speeches he will give.’”

As a result, the pope’s advisers were trying to silence him. When he told a group of Belgian Catholics, “Anti-Semitism is inadmissible. Spiritually we are all Semites,” the Vatican made sure that those remarks were missing from the account of the pope’s remarks in L’Osservatore romano. Kertzer attributes the censorship of the pope to Cardinal Pacelli, who as secretary of state was effectively running the Vatican during Pius XI’s final illness.

While old and very sick, Pius XI was clearly thinking seriously about the problem of race and came across a book called Interracial Justice, by an American Jesuit named John LaFarge, who had worked with African-American congregations during his ministry. The pope was struck by LaFarge’s call for racial tolerance and asked him to write an encyclical on the subject. “Say simply what you would say if you yourself were pope,” he said. But LaFarge’s superior, Jesuit General Ledóchowski, made sure that this did not happen. He appointed two more experienced theologians (whose views were much closer to his own) to help LaFarge draft the encyclical. Rather than forward it to the pope, Ledóchowski sat on it for several months, cutting and modifying, until he produced a much shorter draft that was very far in spirit from LaFarge’s Interracial Justice but that kept some of the original intent and was called “On the Unity of Humankind.” Ledóchowski did not pass on this document to the pope until he was just weeks from death and too sick to do anything with it.

During these same months, Vatican officials succeeded in preventing a break with Mussolini’s government over the racial laws that were passed in the fall of 1938. The Church’s main objection was to the laws’ biological definition of race, which did not exempt Jewish converts to Catholicism, mixed marriages between Jews and Catholics, or their children. But it was difficult for the Church to object to the overall message of the racial laws, since after all, the regime, as the Fascist press enjoyed pointing out, was not doing anything that the Church had not done for centuries and continued to advocate in some of its most authoritative publications.

In May 1937, more than a year before the passage of the racial laws, the Jesuit magazine La Civiltà cattolica published an article on “The Jewish Question and Zionism,” making its point of view clear from the start: “It is an evident fact that the Jews are a disruptive element due to their spirit of domination and their preponderance in revolutionary movements.” A year later, precisely when the regime was beginning to prepare its own racial laws, La Civiltà cattolica published a long, enthusiastic article on newly introduced anti-Semitic legislation in Hungary. “In Hungary,” the journal explained,

the Jews have no single organization engaged in any systematic common action. The instinctive and irrepressible solidarity of their nation is enough to have them make common cause in putting into action their messianic craving for world domination.

As Kertzer writes:

Hungarian Catholics’ anti-Semitism was not of the “vulgar, fanatic” kind, much less “racist,” but “a movement of defense of national traditions and of true freedom and independence of the Hungarian people.”

Thus, despite his evolving thoughts on racism, Pius XI was not really able to mount a comprehensive critique of the racial laws, limiting himself to a rather weak, general plea for Christian mercy. “We recognize,” said Pius, “that it is up to the nation’s government to take those opportune measures in this matter in defense of its legitimate interests and it is Our intention not to interfere with them.” But according to Kertzer, “the pope felt duty-bound to appeal to Mussolini’s ‘Christian sense’ and warn him ‘against any type of measures that were inhumane and unchristian.’”

In a memo the Fascist government assured the Vatican that

the Jews, in a word, can be sure that they will not be subjected to treatment worse than that which was accorded them for centuries and centuries by the popes who hosted them in the Eternal City and in the lands of their temporal domain.

Despite his serious misgivings over the fate of converted Jews, Pius XI eventually accepted the compromise worked out by his senior advisers, which was really no compromise at all: all Jews, including converted Jews, were subject to the legislation.

During the final months of his life, Pope Pius XI, despite being near death, worked feverishly on an address he hoped to give to the Italian bishops on the tenth anniversary of the Lateran Treaty, scheduled for March 1939. He hoped, Kertzer shows, to use the occasion to offer a tough criticism of the regime and the ways it had violated the concordat with the Vatican.

Pius XI felt strongly enough about this speech that he insisted on having copies of it printed up in case he was not well enough to deliver it. Among other things it contained a reference to “all peoples, all the nations, all the races, all joined together and all of the same blood in the common link of the great human family.” He ended up dying a few weeks before the scheduled meeting with the bishops.

Rumors began to reach both Mussolini and his foreign minister and son-in-law Galeazzo Ciano, who had good informants inside the Vatican, about the existence of an explosive document the pope had left behind. As Kertzer writes:

Learning of Mussolini’s concern, Pacelli moved quickly. On February 15 he ordered the pope’s secretary to gather up all written material the pope had produced in preparing his address. He also told the Vatican printing office to destroy all copies of the speech it had printed, copies that Pius had intended to give the bishops. The vice director of the office gave his assurance that he would personally destroy them, so that “not a comma” remained.

Pacelli acted two days after learning of Ciano’s worries that the text of the pope’s speech might get out. Pacelli also took the material that Ledóchowski had sent the pope three weeks earlier—what has since come to be known as the “secret encyclical” against racism—eager to ensure that no one else would see it. The words the pope had so painstakingly prepared in the last days of his life would never be seen as long as Pacelli lived.