“When a monarch can bless, it is best that he should not be touched,” Walter Bagehot wrote in The English Constitution. “It should be evident that he does no wrong. He should not be brought too closely to real measurement. He should be aloof and solitary.”

The impulse behind this advice was less worshipful than shrewd. Monarchy, Bagehot understood, was a magic act; its glamor and beauty—its ability to enlist “the credulous obedience of enormous masses”—could be sustained only as long as the masses were kept at a safe distance from the smoke and mirrors:

Above all things our royalty is to be reverenced, and if you begin to poke about it you cannot reverence it. When there is a select committee on the Queen, the charm of royalty will be gone. Its mystery is its life. We must not let in daylight upon magic.

Bagehot’s warning may have been lost on—or never adequately conveyed to—the younger generations of the modern royal family, but the Queen has heeded it well. She has resisted the magic-killing daylight. Even as her children and grandchildren have succumbed to the lure of self-expression and self-exposure—divulging details of their eating disorders and unhappy marriages, sharing their views on modern architecture, disporting themselves naked in Las Vegas hotel rooms, and so on—she has maintained her potency as a symbol by revealing almost nothing of her personhood. After more than fifty years on the throne, she remains fundamentally unknown by her people. And it is because rather than in spite of this that she is popular among them. (There should be a term for the great many Britons who profess contempt for the royal family, but devotion to their sovereign; they are antimonarchy, but pro-Queen—Queenists, perhaps.)

The playwright Peter Morgan has written two works about, and in praise of, the Queen, both of them suffused with anticipatory nostalgia for the dignity and discipline of her reign. (She will be eighty-nine this year: après elle, le déluge.) Morgan’s screenplay for the 2006 film The Queen, starring Helen Mirren, was set in the weeks following Princess Diana’s death—a period when the Queen came under growing criticism from her subjects for failing to offer an official expression of grief. The film depicted the Queen’s struggles to understand—and, in the end, make grudging concession to—the country’s slightly hysterical mourning and it left little doubt about where its sympathies lay in the contest between her old-school stoicism and the people’s vulgar emotionalism. In one scene, Tony Blair’s press secretary, Alastair Campbell, refers snidely to the Queen’s “coldness” and an infuriated Blair rebukes him:

When you get it wrong, you really get it wrong! That woman has given her whole life in service to her people. Fifty years doing a job she never wanted! A job she watched kill her father. She’s executed it with honor, dignity and, as far as I can tell, without a single blemish, and now we’re all baying for her blood! All because she’s trying to lead the world in mourning for someone who…who threw everything she offered back in her face. And who, for the last few years, seemed committed 24/7 to destroying everything she holds dear!

If the film managed not to melt altogether into a puddle of Queen worship, it was partly due to the restraining influence of Steven Frears’s direction and partly due to Helen Mirren’s uncannily accurate and subtle performance.

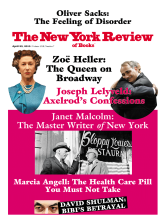

The Audience, Peter Morgan’s latest sprightly piece of Queenist propaganda, which also stars Mirren, takes for its minimal dramatic structure the confidential weekly meetings that the Queen has had with her prime ministers over the course of her reign. Morgan portrays these sessions as comically uptight in form (he makes a lot of hay with periwigged equerries and royal protocol) but exuberant and intimate in content—the sort of encounters in which, when the footmen recede, John Major might weep about his lack of formal education and Churchill might chummily address the Queen as “Lilibet.”

The play assumes little knowledge of recent British history on the part of its audience. (Quite how little is evidenced by the printed guide distributed along with the playbill, which helpfully identifies Churchill as “an inspirational statesman, writer and leader who led Britain to victory in World War II.”) As a result, the political dialogue never rises much above the crudely expository—“The Churchillian dream is over,” Harold Wilson informs the Queen, “the Empire has gone!”—and the PMs themselves are drawn with exceedingly broad strokes. Gordon Brown is Scottish and depressed. Thatcher (a poorly cast Judith Ivey looking like a Lancashire barmaid) is hectoring and pushy. Harold Wilson is prickly and working-class, but ever such a sweetie underneath. (At his first meeting with the Queen, he taunts her with implausible rudeness and scoffs about the poshness of Buckingham Palace, before collapsing in groveling contrition: “Forgive my impertinence. I’m a simple man and I’m intimidated by my surroundings.”)

Advertisement

This broadness of tone extends, alas, even to the Queen. It is to be expected that some of the nuance and charm of Morgan’s film Queen should be lost on the stage—that Mirren’s perfect imitation of the Queen’s throttled diction should have to be replaced by a less authentic, actressy sonorousness, for example. But the exigencies of a theater performance cannot explain the oddly camp quality this Queen has acquired. She mugs. She exclaims. She cocks her eyebrow in the manner of Barbara Stanwyck. She dances a Highland jig.

Which is a problem in a play that presents self-restraint, or at least holding one’s tongue, as the most crucial and onerous of the regal duties. “One thing I think you’ll find all your prime ministers agree on,” David Cameron tells the Queen, “is you have a way of saying nothing yet making your view perfectly clear.” It would be nice if we were ever to see this trick in action, but the Queen never seems to have much need of it. She is far too busy expressing herself in more forthright ways—filling Gordon Brown in on her problems with obsessive-compulsive disorder, telling Harold Wilson how “odious” she finds Ted Heath, musing dreamily on “the unlived lives within us all.”

In one preposterous moment during a conversation with Churchill about whether she should take her husband’s name, Mountbatten, as her own, she cries out, “I may be a queen. I am also a woman and a wife. I want to be in a successful marriage.” It is difficult to believe that the Queen—or any upper-class Englishwoman of her vintage—would utter these words in such a setting, but even harder, perhaps, to credit the idea that she would protest cuts to the royal budget by angrily invoking God’s will.

When John Major cringingly suggests that in order to cut back on expenses, it may be necessary to decommission the royal yacht Britannia, the Queen loses her temper. O reason not the need! She has given her life to her people, she tells him. She has put her role as Queen above marriage, above motherhood. She must have her yacht because she’s worked jolly hard and she was consecrated to do so in the eyes of God. At this point the scene dissolves into a reenactment of her coronation. Strains of Handel’s coronation anthem are heard as the Archbishop of Canterbury anoints her. And then, just before the curtain comes down on the first act, Mirren turns, robed and crowned and sceptered, to face the audience with a basilisk stare.

It is pretty rich that Morgan should ask us to swoon and sympathize with a Queen who invokes the divine right of kings in an argument about why she needs a yacht. And it’s richer still that he should attempt, in the same play, to persuade us that the Queen is a woman of deeply liberal convictions. Harold Wilson tells her that she is a “lefty at heart” who understands the concerns of “ordinary people, working people.” (He cites as evidence her worries about the heating bills at Balmoral.) And the Queen agrees. “That’s the Bobo in me,” she says, referring to her salt-of-the-earth Scottish nanny. Further proof of her socialist inclinations is that she doesn’t like Thatcher and that she is outraged by the racist attitudes of Thatcher’s husband, Dennis. (This, given the well-documented racism of several members of the royal family and of the Duke of Edinburgh in particular, seems particularly fanciful on Morgan’s part.)

Speculative fictions about the “real” Queen behind the royal mask tend to be rather wishful—endowing her with qualities and values that reflect the authors’ own. The Queen in Alan Bennett’s play A Question of Attribution is a canny, rather droll figure, with a distinctly Bennetian line in poker-faced ironies. Sue Townsend’s Queen in the novel The Queen and I is a tough, no-nonsense lady who adapts to life on a council estate with admirable resourcefulness and vim. Such projections are generally harmless enough.

But Morgan’s portrayal of the Queen as a closeted socialist is a fantasy not just about her but about the British class system and about what socialism entails. The comforting illusion he purveys in The Audience is that the crucial divisions in British society are not those of privilege, but of sensibility. The Queen and Harold Wilson get along splendidly—despite their class differences—because they share a love for Britain and its ancient “social fabric.” (It’s ghastly, uncaring arrivistes like Thatcher who are the trouble.) The moral here—that the rich man in his castle and the poor man at his gate need not be at odds with one another, so long as the rich man remembers to be compassionate—seems a particularly sentimental and dishonest way of selling the status quo to a liberal theater audience.

Advertisement

Those who like this sort of thing will be happy to hear that Morgan has not exhausted his interest in Queenist entertainments. His next project, a TV series for Netflix, promises to further explore the relationship between Downing Street and the palace. It is to be called The Crown.