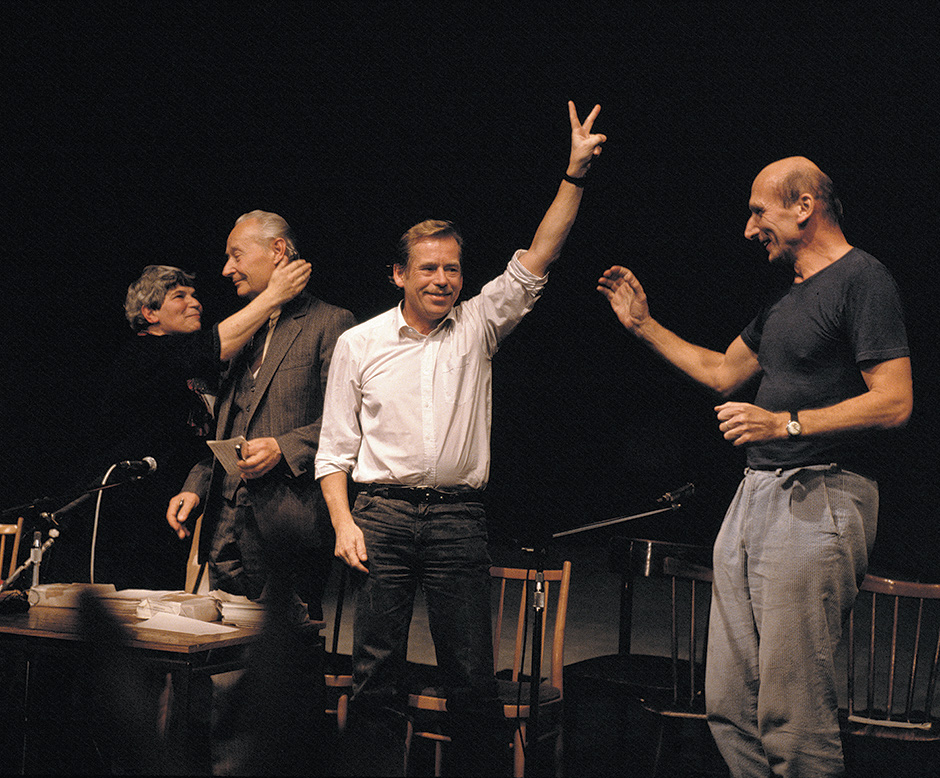

Ian Berry/Magnum Photos

Václav Havel (center) at the Laterna Magika theater, Prague, on November 24, 1989, the day that the Communist Party’s leadership resigned. He is with, from left to right, Rita Klímová, who became the first post-Communist ambassador to the US; Alexander Dubček, who had been the Czechoslovak premier during the Prague Spring; and the music critic and broadcaster Jiří Černy, an important member of the Civic Forum’s coordinating committee.

Few people have been better positioned to write about Václav Havel than Michael Žantovský. He had known Havel since the mid-1980s, and was his press secretary, spokesman, and adviser for two and a half years, from early 1990 to mid-1992. During that time, he says, he spent more time with Havel than he did with his own family. In 1992, as Czechoslovakia slid inexorably toward separation, Žantovský left his position (for reasons I will get into later) and, with Havel’s blessing, went on to a distinguished career of his own, first as ambassador to the United States for the new Czech Republic, then as a senator in Prague (where he chaired the Committee on Foreign Relations and sponsored the country’s first Freedom of Information Act), and finally as ambassador to Israel and most recently Great Britain. But they remained in touch and, Žantovský says, Havel “continued to be generous with his time and friendship, across three continents, and whenever the occasion arose.”

I mention these details about Žantovský’s life in part because anyone reading this entertaining, intimate, and moving account of one of the twentieth century’s better-known public figures will learn little about its author. And yet Žantovský’s voice—that of a natural storyteller with an eye for the memorable anecdote, a mischievous wit, an easy intelligence, and a keen sense of balance and fairness—is so engaging that he becomes a presence in the tale he tells.

This was probably not his intention: in his prologue, he makes it clear that he knows the risks involved in writing about a man for whom, he admits, he feels a genuine love. But that love, as he describes it—a combination of profound respect, affection, and trust—is certainly not blind to the foibles and failings of its object; it is more like an intense friendship forged in combat than a purely emotional attachment. On occasions when Havel’s behavior slips into morally or politically questionable territory—his overuse of prescription drugs, his philandering, his support for the invasion of Iraq—you can almost hear the spokesman arguing with the storyteller over how much to explain and how much to simply let stand. In most cases, the storyteller wins.

Žantovský, however, brings deeper qualifications to the job. Almost thirteen years Havel’s junior, he was a member of a cohort of bright young people who were most deeply affected by the creative forces that Havel and his generation of artists and writers released into society as the pall of Stalinism slowly lifted. Žantovský was an impressionable teenager during Havel’s theatrical heyday in the mid-1960s, and saw the original performances, often several times, of Havel’s early plays like The Garden Party and The Memo, plays that thrilled audiences and that established Havel as an exciting new playwright, even as they alerted the regime’s cultural guardians to the presence of a new troublemaker. Theater was one of the crucibles in which Havel’s complex understanding of politics was forged: he came to see art, and drama in particular, as one of the chief instruments by which a society becomes aware of itself and thus becomes capable of change. Žantovský was one of many in whom that change began to work its way, and it gives his account of Havel’s life and ideas an exceptional cultural depth and sensitivity.

In the early 1970s Žantovský studied psychology in Prague and Montreal, then returned home to work in a clinical setting, where he specialized in the psychology of relationships and sexuality, a background that, as it turned out, positioned him to write with compassion and understanding about aspects of Havel’s private life that most of his other biographers have tended to skirt.

In the 1980s Žantovský turned to the more precarious life of a freelance man of letters, writing lyrics for pop singers and translating writers as diverse as James Baldwin, Nadine Gordimer, Joseph Heller, and Tom Stoppard into Czech. The most unusual item in Žantovský’s work at that time is an extended essay, written in the late 1980s, on Woody Allen, many of whose films and stories he subtitled and translated. (In the interest of disclosure, Žantovský interviewed me for the book under review in one of Allen’s old haunts, the Carnegie Deli on Seventh Avenue.) All of this experience clearly helped to give him the confidence to write the book in English rather than in Czech. It was a deliberate choice: as he told me recently, it gave him some necessary distance from Havel and the often claustrophobic Czech milieu, and allowed him to look at his subject through “a long lens.” For the reader, paradoxically, it lends his portrait of Havel an immediacy that could easily have been lost in translation.

Advertisement

Statesmen who are not writers may leave behind them at most a diary, a memoir, or a forgettable ghostwritten campaign biography or two. But in addition to the mountain of documentary evidence about Havel’s life now accumulating in the Václav Havel Library in Prague, his biographers also have to deal with a prolific writer who was adept at fashioning his own powerful narrative.1

Havel left behind at least three major autobiographical works, each of which was produced under unusual circumstances. First came a collection of letters written in prison in the late 1970s and early 1980s under strict censorship (Letters to Olga); that was followed by a book-length interview conducted via underground courier in the mid-1980s with a Czech journalist in exile, Karel Hvížd’ala (Disturbing the Peace, called Long-Distance Interrogation in Czech); and finally there is his post-presidential memoir, To the Castle and Back, an odd intertwining of three different strands: interviews with Hvížd’ala; slightly unsettling diary entries that suggest, at times, a man on the run from his former life; and memos written to his office staff by a micro-managerial president suffering under the self-imposed burden of writing his own speeches. Over the years, Havel’s own version of his life has acquired an almost canonical status, yet as far as I know, he was never protective of that version nor did he ever try to interfere with how journalists and filmmakers chose to portray him. That may be another reason why Žantovský’s account of his life feels so uninhibited.

Yet despite calling Havel “the ultimate WYSIWYG”—what you see is what you get—Žantovský admits that there remains something about him beyond reach. “Mixed with the warmth and the friendliness,” he writes, was “a certain remoteness…a sense of detachment, an inner impenetrable core that you could never enter.” It’s something other Havel biographers have noted as well.2

Žantovský observes that one of the more obvious “gaping holes” in Havel’s account of his childhood is the almost complete absence of any reference to his mother, Božena. Žantovský speculates that, for all the care and attention she lavished on her two sons (Havel’s brother Ivan is two years younger), there was something missing, perhaps a deeper emotional bond that may have amplified Havel’s natural insecurities and left him with the “deep ambivalence towards the opposite sex” that was evident during his adulthood. “For all his life,” Žantovský writes,

Havel instinctively sought the company of strong, dominant, directive women who could assuage his sense of helplessness and insecurity. At the risk of using a tired psychoanalytical cliché, they all, in one way or another, resembled his mother.

This might be of only passing interest except that, as Žantovský points out, complex and lopsided relations between men and women are frequent motifs in Havel’s plays; otherwise he seemed to prefer the company of men, “where he was more often than not the dominant figure.” When Havel became president, though he tended to surround himself with women (at one point inviting satirical comparisons with Muammar Qaddafi because he had two glamorous female body-guards), he never gave women positions of any authority in his office, with the exception of his legal team and his literary agent, Anna Freimanová. “Ultimately, perhaps,” Žantovský says, “he preferred to rely on women to protect his personal well-being and interests.”

Havel’s decades-long relationship with his first wife, Olga, was in “a category of its own,” Žantovský says. Three years older than Havel, Olga was a strong, blunt, down-to-earth woman from Žižkov, a proudly working-class part of Prague. Olga’s parents were in the Communist Party (a fact Žantovský doesn’t mention), but she was unable to finish high school because she refused to join the Union of Socialist Youth, an act of almost unthinkable defiance at the time. This may have been yet another reason, apart from snobbery, why Havel’s mother never warmed to Olga. Havel fell for her when he was still in his teens and she held him at bay for three years before finally relenting. They married eight years later, in 1964, at a private ceremony in Žižkov. Havel’s parents were not invited.

As Žantovský describes it, theirs was a far from ideal marriage, yet there was a curious stability to it despite Havel’s frequent flings and at least three serious affairs (of which he dutifully informed Olga, to square things with his conscience). Havel’s letters to Olga from prison—to the extent that he directed them specifically to her—mostly concern domestic issues; the one exception, in which Havel reluctantly attempts to write her a kind of “love letter,” was excluded from the “canonical” version of Letters to Olga, and from Havel’s collected works.3

Advertisement

In the end, Olga stood by Havel in her own independent fashion, and though she did not want him to become president, she made a wonderful first lady, somewhat in the Eleanor Roosevelt mold. Despite her dislike of the limelight, she came to be more popular with the Czech public than her husband, and when she died in January 1996 of cancer, the demonstrations of public emotion were almost unprecedented. A year later, Havel married the actress Dagmar Veškrnová in a ceremony in the same office in Žižkov where he had married Olga. In marrying Olga, he had defied his mother; in marrying Dagmar, he was defying Czech public opinion.

Žantovský has arranged the salient points of Havel’s life in forty-seven short chapters like pearls along a chronological string. The pacing is brisk, but the structure allows him, when necessary, to delve more deeply into important moments or relationships or circumstances in Havel’s life. One thing that stands out is how often Havel stirred up controversy by challenging the limits imposed on public discussion by the regime and disrupting its carefully planned agendas. It began with his very first public appearance, before a gathering of young writers in 1956, when Havel had just turned twenty, in which he criticized a new official literary magazine for championing ideas already pioneered by older, now officially ignored writers.4 It continued in a speech delivered to a writer’s meeting in 1965 exposing the shifty liberalism of reform Communists; his 1968 essay “On the Theme of an Opposition” that challenged the limits of the Prague Spring reforms; and his 1975 open letter to the Party’s first secretary and later president, Gustav Husák, which galvanized opposition to the regime around a penetrating critique of post-invasion “normalization” politics.

The following year came his penetrating condemnation of the trial of Ivan Jirous, manager of the Plastic People of the Universe, and other underground musicians that signaled a crucial shift in the tactics of Czechoslovak dissent; and then, in 1978, his most influential essay, “The Power of the Powerless,” commissioned by the Polish dissident Adam Michnik, had a large impact on the conduct of dissent across Central Europe. Long before he became a politician, Havel’s writing was already a significant political force in Czechoslovakia.

Žantovský’s treatment of Havel’s time in prison in the early 1980s, and of his letters to Olga, is revealing even to someone who has spent much time with those letters, as I have. The fact that Havel’s arrest in late May 1979 took place at the home of his mistress at the time helps to explain his early anxiety, especially regarding Olga’s apparent reluctance to write to him. Havel, Žantovský says, knew “his marriage to Olga was on the rocks at exactly the moment when he was least able to do anything about it.”

But Havel’s prison letters are important for other reasons too. Prison censorship restricted Havel to writing about family matters, so he turned to writing about himself, something he had generally avoided doing in the past: “Rarely has anyone engaged in introspection as thorough and as eloquently recorded as Havel did in his letters to Olga,” Žantovský writes.

For a student of the soul, they provide an embarrassment of riches. Havel came to the task equipped with a writer’s lexicon, with self-discipline and with the analytical tools of a student of phenomenology and existential thought.

In this regard, his time in prison was a kind of watershed. If, as Žantovský says, prison made Havel “uniquely well prepared for the single-minded focus towards the tasks ahead,” it also led him to develop a self-referential habit of mind that would mark his writing and many of his utterances ever afterward.

Žantovský’s evocative account of the “Velvet Revolution” and the first two and a half years of Havel’s tenure as president of Czechoslovakia is lively and often hilarious. The first six months of 1990, when Havel staffed his office with old friends from the dissident days, were a time of high spirits and grand initiatives on many fronts. Havel was at the peak of his popularity at home, and this gave his presidency a power and influence beyond his constitutional authority. Internationally he was a celebrity, honored in Washington, feted in New York, and welcomed, albeit with somewhat comic awkwardness, in the Kremlin. Diplomatically, he moved quickly to patch up relations with Germany and repair the ill feelings caused by the expulsion of the Sudeten Germans from Czechoslovakia after World War II. He even found time to oversee a radical renovation of the dreary Communist-era décor in the president’s office in the Prague Castle.

After the first free elections in June 1990, as the reality of democratic politics sank in, the Camelot-like atmosphere around Havel began to evaporate. The organization he had helped to form, the Civic Forum, soon started to split into two factions. Over the next two years, serious cracks in the federation appeared and widened. In an effort to stem the slide toward separation, Havel proposed constitutional amendments he thought would help to resolve the crisis. He even held a rally in Wenceslas Square to pressure parliament to act. Nothing worked.

By early 1992 it was clear that Havel’s personal aversion to political parties and his faith in “nonpolitical politics,” both legacies of his dissident days, were hampering his ability to work with parliament. Žantovský and other close advisers did everything they could to persuade Havel to create some kind of “political machine” or even a cross-party alliance of supporters to back his legislative proposals. Havel politely declined, and Žantovský did the honorable thing and moved on.

Ever afterward Havel would see the breakup of Czechoslovakia as his greatest political defeat. But to be fair, it’s still not clear, even to this day, that he or his ideas could have saved the federation, since the root problem, I believe, was a structural one beyond anyone’s immediate control. The bicameral federal legislature created by the Communist state, and adopted “as is” by the new democracy in its misguided eagerness to ensure some kind of continuity with the past, was not a real parliament, but rather a pseudo-institution that merely appeared to balance Czech and Slovak interests, while maintaining the Party’s absolute control over everything.

Moreover, after 1989, none of the major new political parties had a federal organization or federal representatives, which meant that, apart from the now utterly discredited Communist Party, no one in the new democracy, least of all Havel, had either the time, the experience, or the means to deal with a crisis of that magnitude and urgency.5 Probably nothing short of a radical revamping of the electoral laws and major constitutional amendments could have averted the breakup. The miracle was that it happened in such a civil fashion, and that may have been due, in part, to Havel’s calming influence.

Havel became president of the new Czech Republic in 1993, but he never really regained the enthusiasm for the job he displayed in those first two and a half years. There were remarkable achievements in which Havel had an important part: the country joined the EU, he pushed hard for NATO expansion, and his renown continued to give the country a positive international profile. At the same time, however, he had to endure the hostility of the most powerful politician in the country, Václav Klaus, who openly opposed most of his ideas. Havel’s deep distrust of party politics and its corollary, his abiding belief in the importance of renewing the civil society, were two issues on which the two men were never able to see eye to eye, to the detriment of the country’s democratic evolution.

Their political differences had a common source that neither man may have fully understood. The only model of party politics immediately available to them was the Communist Party, which was not designed to compete for the right to govern, but rather to seize and hold power, exclusively and forever if possible. Klaus, a market economist, took from that model his understanding that even in a multiparty democracy with free elections, political parties exist to exercise power, and, Žantovský says, he saw nongovernmental organizations as “just so many self-appointed advocacy groups for partial interests”—in other words, as barely legitimate constraints on power, and he consistently blocked Havel’s efforts to give nonprofit organizations special tax status.

Havel distrusted political parties for the same reason Klaus embraced them, and that prevented both men from seeing that in a democracy, political parties are not antithetical to civil society but a part of it. Every social organization, be it a political party or a kennel club, must follow a governance structure that is, in essence, a school of democracy.

It would be wrong to come away from Žantovský’s book with the impression that Havel’s story illustrates the “great man” theory of history, that historical events are driven by strong leaders, or that he somehow embodied the ancient dream of a “philosopher-king.” Havel’s leadership was of a different kind, one that seems more unusual the more closely one examines it. Havel epitomized a moment in history that he helped shape, but the moment was also bigger than he was.

He created no lasting institutions, but he did speak for his country’s higher aspirations, and by identifying qualities that mattered—responsibility, respect for truth, the belief that acting freely expands the potential of freedom—he inspired people to unlock these qualities in themselves. His authority was a distillation of the authority that everyone has in a free society: the capacity to act in harmony with one’s conscience, without regard for personal gain or personal safety.

Havel’s kind of authority is impossible to institutionalize or codify, and he did not try; he did not revolutionize the office of the president, but he made the most of it, just as he made the most of his unofficial leadership of the dissident movement. And though his last years as president were not happy ones, burdened as they were by illness, insecurities, and a loss of popularity, the important thing, obvious to anyone who has known the country before and after Havel, is that the Czech Republic now has the very thing he most wished for it to have: an active civil society, in which the peculiar Czech genius for creating small institutions driven by vision and passion can have full rein, and which, if it continues to flourish, may eventually do what Havel hoped it would—infect the country’s political culture with the same sense of responsibility for the public good that drove his best efforts, and that is still democracy’s best hope.

-

1

There have been at least six Havel biographies in English before this one, all written before his death. They are, in order of appearance: Michael Simmons, The Reluctant President: A Political Life of Václav Havel (Methuen, 1991); Eda Kriseová, Václav Havel, translated by Caleb Crain (St. Martin’s, 1993); Jeffrey Symynkywicz, Václav Havel and the Velvet Revolution (Dillon, 1995); John Keane, Václav Havel: A Political Tragedy in Six Acts (Basic Books, 2000); James F. Pontuso, Václav Havel: Civic Responsibility in the Postmodern Age (Rowman and Littlefield, 2004); Carol Rocamora, Acts of Courage: Václav Havel’s Life in the Theater (Smith and Kraus, 2004). There are, of course, other books written in Czech, some of them scurrilous takedowns, others serious studies. The most recent is Václav Havel: Duchovní portrét v rámu české kultury 20. století (Václav Havel: An Intellectual Portrait in the Framework of Twentieth-Century Czech Culture) by Martin C. Putna (Václav Havel Library, 2011). The author is a former director of the Václav Havel Library. ↩

-

2

John Keane wrote that Havel “is not fully comprehensible,” Michael Simmons that Havel “has given little away.” ↩

-

3

In it, Havel, responding to Olga’s complaints that he is sometimes “cold…alien and impersonal” toward her, writes: “Periods of greater or lesser alienation are simply part of life and it wouldn’t be normal if we never experienced such things. The main thing is that it has no influence on what is essential, and by now it would be very difficult for this ever to be so. So I’m fond of you…it’s love—love as dependency—love as devotion—love as destiny. It’s a lifetime thing. At least on my part—I don’t wish to speak for you.” From letter number 42, dated August 9, 1980, translated from a facsimile provided to me by the Václav Havel Library. ↩

-

4

Havel gives a full account of this event in Disturbing the Peace (Knopf, 1990), pp. 29–33. ↩

-

5

The one exception was Václav Klaus’s Civic Democratic Party (ODS). Before the elections of June 1992 that set the stage for Czechoslovakia’s breakup, the ODS attempted to expand into Slovakia, and did offer a federal slate of candidates. It failed, however, to elect a single candidate in Slovakia, and it’s still an open question whether Klaus acted out of a last-minute effort to bring the country together by extending his authority into Slovakia, or as a way of demonstrating that a majority of Slovak voters rejected his radical economic reforms and so were a millstone better jettisoned in the interests of rapid transformation. In any case, after that election, Klaus—as the new Czech premier—became one of the strongest proponents of separation. ↩