1.

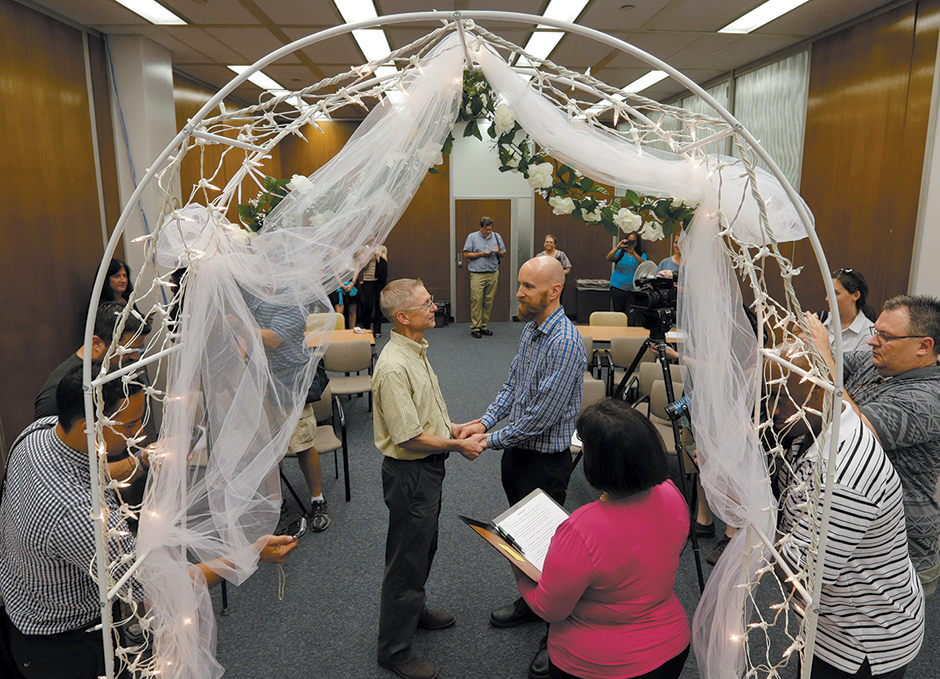

At the end of June, the Supreme Court will likely declare that the Constitution requires states to recognize same-sex marriages on the same terms that they recognize marriages between a man and a woman. If it does, the decision will mark a radical transformation in both constitutional law and public values. Twenty-five years ago, the very idea of same-sex marriage was unthinkable to most Americans; the notion that the Constitution somehow guaranteed the right to it was nothing short of delusional.

One sign of how far we have come is that the principal ground of political contention these days is not whether same-sex marriages should be recognized, but whether persons who object to such marriages on religious grounds should have the right to deny their services to couples celebrating same-sex weddings. Opponents of same-sex marriage can read the shift in public opinion as well as anyone else: a 2014 Gallup poll reported that, nationwide, 55 percent of all Americans, and nearly 80 percent of those between eighteen and twenty-nine, favor recognition of same-sex marriage. Today, same-sex couples have the right to marry in thirty-seven states and the District of Columbia. And come June, most legal experts expect the Supreme Court to require the remainder to follow suit.

Having lost that war, opponents of same-sex marriage have opened up a new battlefield—claiming that people with sincere religious objections to it should not be compelled to participate in any acts that are said to validate or celebrate same-sex marriage. There is an obvious strategic reason for this. One of the problems for opponents of same-sex marriage was that they could not credibly point to anyone who was harmed by it. Proponents, by contrast, could point to many sympathetic victims—couples who had lived in stable, committed relationships for years, but were denied the freedom to express their commitment in a state-recognized marriage, and who were therefore also denied many tangible benefits associated with marriage, including parental rights, health insurance, survivor’s benefits, and hospital visitation privileges. Claims that “traditional marriage” would suffer were, by contrast, abstract and wholly unsubstantiated.

Focusing on religiously based objectors puts a human face on the opposition to same-sex marriage. Should the fundamentalist Christian florist who believes that same-sex marriage is a sin be required to sell flowers for a same-sex wedding ceremony, if she claims that to do so would violate her religious tenets? There are plenty of florists, the accommodationists argue, so surely the same-sex couple can go elsewhere, and thereby respect the florist’s sincerely held religious beliefs. Should a religious nonprofit organization that makes its property available to the general public for a fee be required to rent it for a same-sex wedding? Should a religious employer be compelled to provide spousal benefits to the same-sex spouse of its employee? Should Catholic Charities’ adoption service have to refer children to otherwise suitable homes of married same-sex couples? At its most general level, the question is whether religious principles justify discrimination against same-sex couples.

2.

In late March, Indiana Governor Mike Pence signed into law the Indiana Religious Freedom Restoration Act (RFRA), a state law that requires officials to exempt those with religious objections from any legal obligation that is not “essential” and the “least restrictive means” to serve “a compelling state interest.” Arkansas enacted a similar law at the beginning of April. Georgia and North Carolina are considering doing so. And nineteen other states already have such laws, which could permit individuals to cite religious objections as a basis for refusing to abide by prohibitions on discrimination in public accommodations, employment, housing, and the like.

The Indiana and Arkansas laws prompted strong objections from gay rights advocates and leaders of the business community, including Apple, the NCAA, Walmart, and Eli Lilly. They see the laws as thinly veiled efforts to establish a religious excuse for discrimination against gay men and lesbians. Governor Pence initially dismissed these objections as unfounded, but as criticism mounted, Indiana legislators passed an amendment specifying that the law

does not authorize a provider to refuse to offer or provide services, facilities, use of public accommodations, goods, employment, or housing…on the basis of race, color, religion, ancestry, age, national origin, disability, sex, sexual orientation, gender identity, or United States military service.

Most of the other state RFRAs, however, have no such antidiscrimination language. In Arkansas, Governor Asa Hutchinson responded to criticism by getting the legislature to tailor the law more closely to the federal Religious Freedom Restoration Act, but that law has no antidiscrimination language, and for reasons discussed below, it is far from clear that this revision will stop the law from being invoked to authorize religiously motivated discrimination.

In addition, still other state laws that have received far less attention specifically grant religious exemptions from a variety of legal obligations regarding same-sex marriage. In fact, to date every state except Delaware that has adopted same-sex marriage by legislation has included a religious exemption of some kind. They vary in their details, but among other things, they allow clergy to opt out of conducting marriage ceremonies; permit religiously affiliated nonprofit organizations to deny goods and services to same-sex weddings; and allow religiously affiliated adoption agencies freedom to deny child placements with same-sex married couples. Most were enacted as part of a political bargain, designed to ease passage of laws recognizing same-sex marriage.

Advertisement

At bottom, all of these laws pose the same question: How should we balance the rights of gay and lesbian couples to equal treatment with the free exercise rights of religious objectors?

Under the US Constitution, the answer to this question is clear. The state violates no constitutionally protected religious liberty by imposing laws of general applicability—such as antidiscrimination mandates—on the religious and nonreligious alike. In 1990, the Supreme Court ruled, in a decision written by Justice Antonin Scalia, that being subjected to a general rule, neutrally applied to all, does not raise a valid claim under the First Amendment’s free exercise of religion clause, even if the rule burdens the exercise of one’s religion.

The case, Employment Division v. Smith, involved a Native American tribe that sought an exemption from a criminal law banning the possession and distribution of peyote; the tribe argued that the drug was an integral part of its religious ceremonies. The Court rejected the claim. Justice Scalia reasoned that to allow religious objectors to opt out of generally applicable laws would, quoting an 1878 Supreme Court precedent, “make the professed doctrines of religious belief superior to the law of the land, and in effect…permit every citizen to become a law unto himself.” The Court accordingly ruled that laws implicate the free exercise clause only if they specifically target or disfavor religion, not if they merely impose general obligations on all that some religiously scrupled individuals find burdensome.

Even before the Court in Employment Division v. Smith adopted this general rule, it rejected a claim that religious convictions should trump antidiscrimination laws. The IRS had denied tax-exempt status to Bob Jones University, a religious institution that banned interracial dating, and to Goldsboro Christian Schools, Inc., which interpreted the Bible as compelling it to admit only white students. The religious schools sued, asserting that the IRS’s denial violated their free exercise rights. In Bob Jones University v. United States, the Court in 1983 summarily rejected that contention, asserting that the state’s compelling interest in eradicating racial discrimination “outweigh[ed] whatever burden denial of tax benefits places on petitioners’ exercise of their religious beliefs.” If the state seeks to eradicate discrimination, the reasoning goes, it cannot simultaneously tolerate discrimination.

Under these precedents, the Constitution plainly does not compel states to grant religious exemptions to laws requiring the equal treatment of same-sex marriages. Laws recognizing same-sex marriages impose a general obligation, do not single out any religion for disfavored treatment, and in any event further the state’s compelling interest in eradicating discrimination against gay men and lesbians.

But can or should states adopt such exemptions as a policy matter? In some instances, to be sure, it seems appropriate to accommodate religious scruples. Everyone agrees, for example, that a priest should not be required to perform a wedding that violates his religious tenets. But it is not at all clear that those who otherwise provide goods and services to the general public should be able to cite religion as an excuse to discriminate.

Take the fundamentalist florist. Proponents of an exemption insist that the same-sex couple denied flowers can find another florist, while the florist would either have to violate her religious tenets or lose some of her business. But this argument fails to take seriously the commitment to equality that underlies the recognition of same-sex marriage—and the harm to personal dignity inflicted by unequal treatment. Just as the eradication of race discrimination in education could not tolerate the granting of tax-exempt status to Bob Jones University, even though plenty of nondiscriminatory schools remained available, so the eradication of discrimination in the recognition of marriage cannot tolerate discrimination against same-sex marriages.

Justice Robert Jackson got the balance right when he stated, in 1944, that limits on religious freedom “begin to operate whenever [religious] activities begin to affect or collide with liberties of others or of the public.”1 James Madison struck the same balance, noting that religion should be free of regulation only “where it does not trespass on private rights or the public peace.”2 When a religious principle is cited to deny same-sex couples equal treatment, it collides with the liberties of others and trespasses on private rights, and should not prevail.

Advertisement

The fact that many of the state laws specifically single out religious objections to same-sex marriage for favorable treatment may itself pose constitutional issues under the First Amendment’s clause prohibiting the establishment of religion. While states are permitted some leeway to accommodate religion, the establishment clause forbids states from favoring specific religions over others, or religion over nonreligion. And when states accommodate a religious believer by simply shifting burdens to third parties, such as when religiously motivated employers are permitted to deny benefits to same-sex spouses of their employees, the state impermissibly takes sides, favoring religion. In Estate of Thornton v. Calder (1984), for example, the Supreme Court held that the establishment clause invalidated a state requirement that businesses accommodate all employees’ observations of the Sabbath, regardless of the impact on other workers or the business itself. State laws granting exemptions for religious objectors to same-sex marriage both give preference to religious over other conscientious objections and shift burdens to same-sex couples. Such favoritism is not only not warranted by the free exercise clause, but may be prohibited by the establishment clause.

3.

The “religious freedom restoration” laws that Indiana, Arkansas, and nineteen other states have adopted do not single out same-sex marriage as such, but they also have serious flaws. These statutes are almost certainly constitutional under existing doctrine, since they are modeled on the federal Religious Freedom Restoration Act, enacted in 1993 in response to the Smith decision. That’s the statute the Supreme Court relied upon last year in Burwell v. Hobby Lobby to rule that the Department of Health and Human Services must accommodate for-profit corporations that object on religious grounds to providing insurance coverage to their employees for certain kinds of contraception. (Significantly, the Court in Hobby Lobby found that the religious corporations’ objections could be accommodated without imposing any cost on their female employees, by extending to those for-profit businesses an existing HHS accommodation that required insurance providers to provide contraception at no cost to the employees of objecting nonprofit organizations).3

The federal and state RFRAs provide, as a statutory matter, what the Court refused to provide as a matter of constitutional law in the Smith decision. They require the government to meet a very demanding standard to justify any law, no matter how neutral and generally applicable, that imposes a “substantial burden” on anyone’s exercise of religion. Because the courts are reluctant to second-guess individual religious commitments, the “substantial burden” threshold is often easily met: an individual need only articulate a plausible claim that the law requires him to do something that violates his religious principles. Religious objections could be raised to antidiscrimination laws, criminal laws, taxes, environmental and business regulations, you name it; the only limit is the creativity of religious objectors.

Once a religious objection is raised, the RFRA laws require the state to show not only that it has a “compelling” reason for denying a religious exemption, but that no more narrowly tailored way to achieve its ends is possible. This language appears to direct courts to apply the same skeptical standard—called “strict scrutiny”—applied to laws that explicitly discriminate on the basis of race, or that censor speech because of its content. This standard is so difficult to satisfy that it has been described as “strict in theory, but fatal in fact.” If the RFRAs were literally enforced, many state laws would not survive that standard of review. They appear to give religious objectors what the Court in Smith properly refused—“a private right to ignore generally applicable laws.”

Perhaps for this reason, courts have not interpreted state RFRAs literally, but have instead generally construed them to uphold laws that impose a burden on religion as long as the state has a reasonable justification for doing so. They have looked to the purpose of the RFRAs rather than to their literal language; the laws were designed, after all, to “restore” the constitutional protection of religious free exercise that existed prior to the Smith decision, and while the Supreme Court before Smith sometimes spoke in terms of compelling interests and least restrictive means, its actual application of the free exercise clause was much more measured. Thus, there have been relatively few successful RFRA lawsuits in the state or federal courts.

The courts have resisted applying strict scrutiny to religious freedom claims for good reason. Strict scrutiny is triggered by regulations of speech only where the state censors speech because of its content, such as when a state bans labor picketing or regulates political campaign advocacy. In equal protection cases, the Court applies strict scrutiny only to those rare laws that intentionally draw distinctions based on race, ethnicity, national origin, or religion, such as race-based affirmative action. By contrast, as Justice Scalia noted in Smith, a religious objection can be raised to virtually any law. Applying the same scrutiny to claims of religious freedom would therefore have few meaningful limits, and would give religious objectors a presumptive veto over any law they claimed infringed their religious views.

But there is reason to believe that judicial interpretation of RFRAs may change. The Supreme Court in Hobby Lobby interpreted the federal RFRA to impose a much more demanding, pro-religion standard of review than had ever been imposed before. Encouraged by this development, over one hundred lawsuits have been filed under the federal RFRA challenging the Affordable Care Act’s requirement that health insurance plans cover contraception. Some state courts may well follow the Supreme Court’s lead and apply their state RFRAs more aggressively. And now that many states have been required by federal courts to recognize same-sex marriage, some state judges may be inclined to push back through interpretation of state RFRAs permitting religious exemptions.

When Smith was decided, the prohibition of the peyote ceremony seemed to many an unfair deprivation of the religious rights of Native Americans. Religious groups across the spectrum condemned the decision, and a coalition of liberals and conservatives joined together to endorse the enactment of the federal RFRA. The law was supported by the ACLU, the American Jewish Congress, and the National Association of Evangelicals, among many others; it passed the House unanimously, and passed 97–3 in the Senate. Many argued, with justification, that the Court’s approach in Smith was insensitive to religious minorities. As the peyote case illustrated, minority religions are unlikely to have their concerns taken seriously by the majority through the ordinary democratic process. And if a generally applicable law does interfere with the exercise of religion, the bill’s proponents asked, shouldn’t the state bear a burden of justification?

The problem is not so much that RFRAs create a presumption in favor of religious accommodation, but that the presumption is at once so easily triggered and so difficult to overcome. Advocates for religious liberty and marriage equality might find common ground were they to support modified RFRAs that would impose a less demanding standard of justification, requiring states to show that permitting a religious exemption would undermine important collective interests or impose harm on others.

The stringent standard imposed by RFRAs, by contrast, means that anytime anyone objects on religious grounds to any law, he or she is entitled to an exemption unless the state can show that it is absolutely necessary to deny the exemption in order to further a compelling end. Because these laws impose such a heavy burden of justification, they effectively transfer a great deal of decision-making authority from the democratic process to religious objectors and the courts.

Instead of the polity deciding when to grant particular religious exemptions from a specific law, RFRAs transfer to courts the power to decide that question—subject to a strong presumption that individual religious claims take precedence over democratically chosen collective goals.

Religious liberty has an important place in American society, to be sure. Accommodation of religious practices is a sign of a tolerant multicultural society—so long as the accommodation does not simply shift burdens from one minority to another. The freedom to exercise one’s religion is a fundamental value, but like other values, it has its limits. It is not a right to ignore collective obligations, nor is it a right to discriminate. Those who oppose same-sex marriage should be free to express their opposition in speech to their heart’s (and religion’s) content, but not to engage in acts of discrimination. As Oliver Wendell Holmes Jr. is said to have remarked: “The right to swing my fist ends where the other man’s nose begins.”

-

1

Prince v. Massachusetts, 321 U.S. 148, 177 (1944) (Jackson, J., concurring). ↩

-

2

James Madison, Writings (Library of America, 1999), p. 788. ↩

-

3

For analysis of the Hobby Lobby case, see my essays “How Religious Rights Can Challenge the Common Good,” The New York Review, May 8, 2014, and “Supreme Court: It Could Have Been Worse,” NYRblog, June 30, 2014. ↩