1.

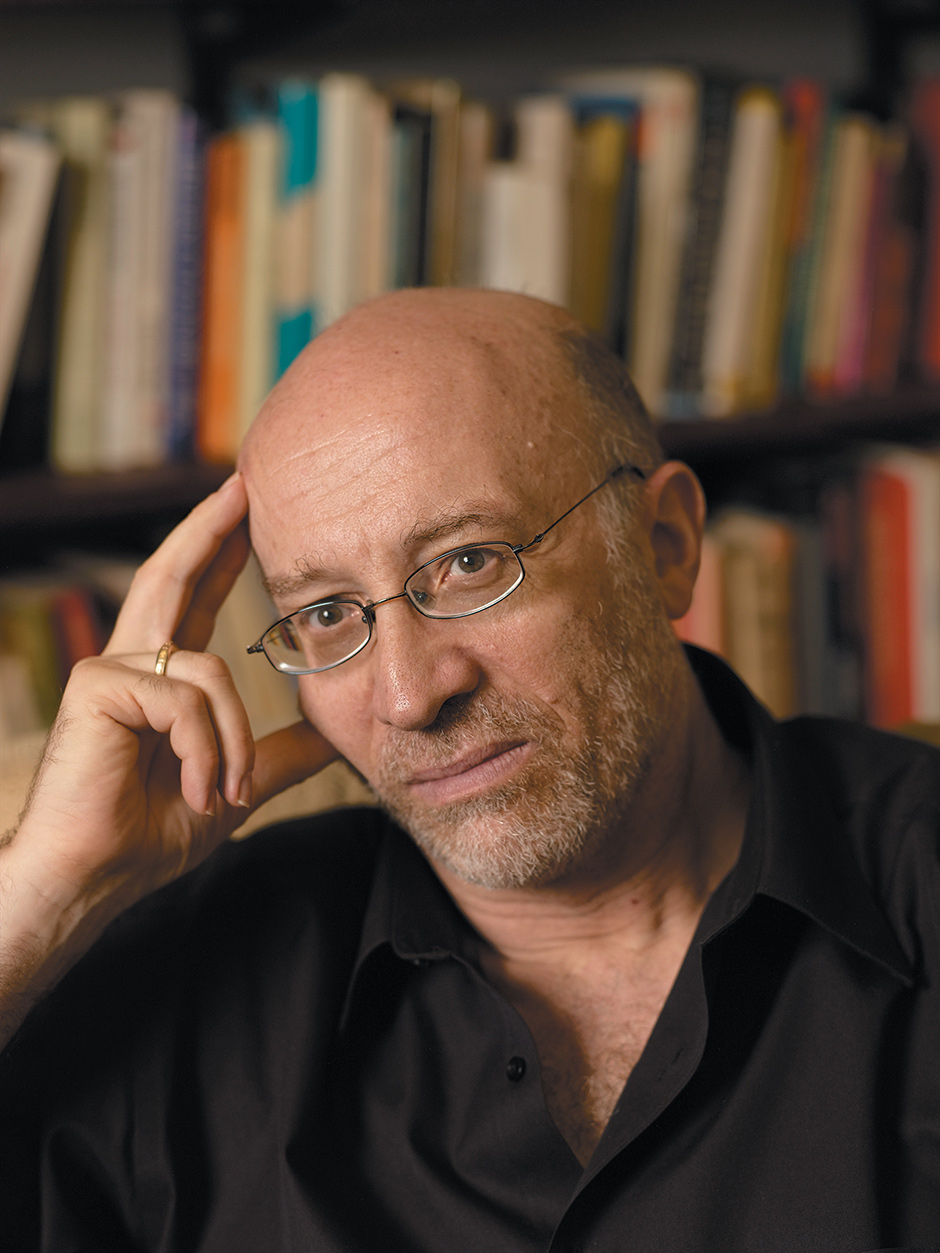

More than a decade ago, I met Tony Judt for the first time. We drank whiskey in the lobby of a smart London hotel. He looked a little out of place: the scholar among the expensively dressed international businessmen and women, a visiting American professor who was also a former Londoner, born and raised in some of the city’s shabbiest neighborhoods.

Only a few months earlier, in October 2003, The New York Review had published Judt’s best-known or, more accurately, most notorious essay, “Israel: The Alternative.” There he had declared the Middle East peace process dead, and the prospect of a two-state solution to the Israel–Palestine conflict buried along with it. It was time, he had argued, to think afresh, even to turn toward the notion of a single state in historic Palestine, one that would be a secular home to both Jews and Arabs. Yes, it would mean the dissolution of the Jewish state and an end to the Zionist movement that had given it birth. But perhaps there was no longer a place in the world for such a state. Surely Israel had become “an anachronism. And not just an anachronism but a dysfunctional one.”

That essay had brought the roof down on Judt’s head. He was not only denounced in the most vicious terms by the usual suspects on the American Jewish right and barred from speaking on at least one occasion, but also condemned by former friends and allies. He had been a contributing editor at The New Republic but suddenly found his name removed from the masthead. A onetime activist in a Zionist youth movement, a volunteer during Israel’s 1967 war who had put his Hebrew to use as a translator, Judt was now declared by Israel’s most unbending cheerleaders to be a nonperson.

It struck me at the time that his critics were misreading the essay, or at the very least misunderstanding its intent. A kind of confirmation came when I asked Judt if he would have published that same piece not in The New York Review but in its UK counterpart, the London Review of Books. He paused, thinking through the implications, and finally said no, he would not.

The simple explanation was that Judt understood the contrast in the climate of opinion between the two countries. In Britain (and Europe) hostility to Israel was already deeply entrenched: Ariel Sharon had recently reincurred the deep enmity of mainstream liberal opinion, not least through his crushing of the second intifada. In the US, in New York especially, the prevailing assumptions were in Israel’s favor. Indeed, a blanket of complacency and unquestioning solidarity tended to muffle any genuine debate. In a subsequent exchange in these pages, where Judt took on several of his antagonists, he wrote:

The solution to the crisis in the Middle East lies in Washington. On this there is widespread agreement. For that reason, and because the American response to the Israel–Palestine conflict is shaped in large measure by domestic considerations, my essay was directed in the first instance to an American audience, in an effort to pry open a closed topic. [my italics]

In the same paragraph, Judt added that he was “very worried about the direction in which the American Jewish community is moving.” It seemed to me that his essay, and especially its vehemence, was designed to stir US Jews from their lethargy. (In Britain and Europe, the topic was far from closed and hardly needed prying open.) Viewed like that, “Israel: An Alternative” was less a detailed statement of binationalism than a provocation, forcing US supporters of Israel to confront what the death of the two-state solution would entail. In that same exchange, Judt conceded that he was hardly offering an immediate policy prescription:

When I wrote of binationalism as an alternative future, I meant just that. It is not a solution for tomorrow…. If the problem with a two-state solution is that Israel’s rulers won’t make the necessary sacrifices to achieve it, how much less would they be willing to sacrifice Israel’s uniquely Jewish identity? For the present, then, binationalism, is—as I acknowledged in my essay—utopian.

That encounter in the London hotel lobby offered a glimpse of a crucial aspect of Judt’s character: his refusal to surrender to dogma. An ideologue would have insisted that the truth was the truth was the truth and that there could be no adjustment for context. But Judt understood that the same argument could have different meanings in different situations, that even the most firmly held principles had to take account of variations in time or place, and that, sometimes, a position had to shift.

Freedom from dogma is the golden thread that runs through When the Facts Change, a collection of Judt’s essays—many of them first published in The New York Review—from 1995 until his premature death in 2010, aged sixty-two, from Lou Gehrig’s disease. The volume is staggeringly broad in its range, testament to the extraordinary eclecticism of Judt’s interests and knowledge. He writes learnedly on Israel, France, Britain, the United States, Central Europe, the Holocaust, social democracy, and much else. He is able to analyze both contemporary politics and modern history with deep erudition. There are profiles of Polish intellectuals alongside demolitions of Bush-era foreign policy, hymns to the glories of the railways next to detailed surveys of European welfare spending.

Advertisement

The common element is intellectual pragmatism. The title, apparently chosen by Judt’s young son, refers to the riposte regularly attributed to John Maynard Keynes and cited often by the author: “When the facts change, I change my mind. What do you do, sir?”

That this was a Judt mantra we learn from a tender, affecting introduction written by the book’s editor and Judt’s widow, Jennifer Homans. Her opening line promises to “separate the man from the ideas.” But the piece has the opposite effect. Her sketch of Judt, depicting him as both a scholar—including a fascinating account of his writing method, down to the color-coded research notes—and a husband, serves to root what follows in lived experience, to acknowledge the role that Judt’s personal history played in his thinking. It’s wholly fitting since this too is a Judt theme. Throughout the collection, it is clear that he did not see ideas as existing in some realm of pure abstraction, but understood that people, individuals as much as nations, hold ideas as a consequence of the lives they have led.

In that sense it is illuminating rather than indulgent for her to recall the way a domestic dispute between them—over the sale of an unwanted house in Princeton—was resolved. He had wanted to keep it, until Homans laid out the facts in a spreadsheet:

Commuter train schedules, fares, total hours spent at Penn Station, the works. He studied it carefully and agreed on the spot to sell the house. No regrets, no remorse, no recriminations, no further discussion necessary…. When the facts changed—when a better, more convincing argument was made—he really did change his mind and move on.

This is the lens through which to view Judt’s commentary on Israel, including the infamous 2003 essay. He adjusted his position in the light of the facts. For decades he had been an advocate of two states, yet seeing the expanding project of Jewish settlement in the occupied territories that would eventually have to become a Palestinian state, he concluded that Israel was not ready to take even the minimal steps required to make such an outcome possible. Accordingly, he looked for other options. One of those was binationalism, but here too he was ready to be swayed by the facts. In 2009, he wrote that he might still favor a one-state solution “if I were not so sure that both sides would oppose it vigorously and with force. A two-state solution might still be the best compromise….”

As if to prove the enduring power of the 2003 essay, at least one review of this posthumous collection has focused on that single piece almost exclusively, failing to take account of Judt’s postscript on the affair or his subsequent writing on the topic contained in the very same volume. This is not just questionable practice, it also misses something essential about Judt’s work: he was no peddler of pickled dogmas, reselling the same, unchanging ideas in one article after another. He was constantly thinking out loud, interrogating his earlier positions, and altering them in the light of changing events. It means that any reader coming to this anthology looking for a fixed program or ordered manifesto will be disappointed.

Which is not to say that Judt’s writings were not guided by a coherent set of principles. For one thing, resistance to dogma was, for him, almost an ideology in itself. It led him to loathe totalitarianism in all its forms. He located fascism and the horrors of Nazism at the center of the twentieth century, casting their shadow over all that followed. He echoed and endorsed Hannah Arendt’s insistence that “the problem of evil” would be the defining question of the postwar era and he wrestles with it in this collection more than once.

Of course for a liberal historian, born in Britain with a later career in the US, to be unwavering in his condemnation of Hitler’s wickedness involved no risk. Where Judt showed courage was in his willingness to look at monstrous crimes committed in the name of the left. He is acid in his denunciation of Stalinist murder and unforgiving of those leftists who were ready to look the other way or make excuses.

Advertisement

The first piece in this collection assesses, for example, the revered British Marxist historian Eric Hobsbawm. Judt admires the older man’s scholarship but laments his failure, as Judt put it in an earlier essay (republished in the 2008 collection Reappraisals), “to stare evil in the face and call it by its name.” He condemns Hobsbawm for remaining stuck in the 1930s, for failing to shake off the old Manichaean categories that equated left/right, Communist/Fascist, and progressive/reactionary with good/evil. Had he done so, Judt argues, he would have seen where fascism and Soviet communism came to resemble each other.

Plenty of youthful Marxists went through Judt’s process of disenchantment and ended up far on the other side, reinvented as hawkish anti- Communists and neoconservatives. Judt made no such move: he would not trade one dogma for another. Indeed, he was a stern opponent of the Bush administration and its trampling on international norms. But he staked out a liberal terrain of his own, beholden to neither the anti-Western left nor the America-first right. So he could slam Donald Rumsfeld and Dick Cheney, blaming them for, among other things, shrinking the power of America’s example and therefore risking its appeal to the free nations of the world:

This would spell the end of “the West” as we have understood it for half a century. The postwar North Atlantic community of interest and mutual friendship was unprecedented and invaluable: its loss would be a disaster for everyone.

That’s not a sentence one can imagine being written by Noam Chomsky. Not that Judt was merely an exponent, however eloquent, of the soggy center ground. His stance against the extremes, the easy binaries of hard left or hard right, was strongly held and forcefully argued. For him pragmatism was a humane creed, compromise itself an ideal. The alternative was an absolutism that could only be secured by blood.

In the final year of his life, by then a quadriplegic and reliant on awkward breathing equipment, he delivered a lecture at New York University that amounted to a spirited defense of social democracy, an idea battered by three decades of the Thatcher-Reagan model. He pleaded for a halt to the unraveling of the welfare state and the public sector, built so painstakingly through the postwar years:

That these accomplishments were no more than partial should not trouble us. If we have learned nothing else from the twentieth century, we should at least have grasped that the more perfect the answer, the more terrifying its consequences. Imperfect improvements upon unsatisfactory circumstances are the best that we can hope for, and probably all we should seek.

Perfection, he understood, was the goal of murderous dictators. The unglamorous, bloodless business of modest amelioration was a better ideal.

That much is clear in Judt’s pantheon of heroes. Homans lists them, taking care to say they were not quite heroes but rather “shades…who were all around all the time.” Among them: Keynes, Isaiah Berlin, Raymond Aron, A.J.P. Taylor, Albert Camus, “whose photo sat on his desk,” and, inevitably, George Orwell. This collection includes encomia to some of those and the same admired traits recur. He praises Taylor for a willingness to write “against the grain of his own prejudices.” His eulogy for Leszek Kołakowski lauds the Polish thinker’s ability to reject Marxism without concluding either that socialism “had been an unmitigated disaster” or that there was no point in striving to improve the condition of humanity. Judt valued those who, like him, sought to save the baby even as they chucked out bucketloads of bathwater.

In the mid-1990s, both Bill Clinton and Tony Blair were fond of speaking of “the vital center.” The phrase often sounded hollow, as empty as the “third way.” But to read Judt is to see that it can contain meaning. It can refer to skepticism in the face of dogma; a refusal to believe that because one part of a program has merits or flaws, the entire program has to be accepted or rejected; an ability to contain moral complexity, to admit and interrogate one’s own contradictions. In Tony Judt, the notion of the vital center found life.

2.

The question that hangs over any anthology of journalism, even one of the highest quality, is always the same: What relevance does it have for today? In Judt’s case the easy answer is to point to evidence of uncanny prescience. His essay “Europe: The Grand Illusion,” is a typical example. It was written in 1996, three years before the launch of the euro in a period fervent with excited eurofederalism. It was written by a man free of the sulking, Little Englander introversions of many of his fellow Brits: Judt spoke French, German, Italian, Czech, and some Spanish and had made his name as a historian of France. He had only just established, in 1995, the Remarque Institute, dedicated to bringing Europe and his newly adopted home, the United States, closer together. If anyone could have been expected to be a euroenthusiast, it was surely Tony Judt.

Yet in 1996 he was full of realism and caution. “The politics of immigration will not soon subside,” he wrote, reading the runes correctly. As it expanded, the European Union was rapidly dividing into “winners” and “losers,” he noted, describing accurately the situation that obtains now, nearly two decades later. The losers, he warned, would turn to nationalism. Right again.

Still, it’s not for his powers of prophecy that people continue to look to Judt. (At the Ukrainian Catholic University in Lviv, even as civil war rages, there is currently a seminar for graduate students titled simply “Reading Tony Judt.”) I would suggest instead three other factors that make his work strong and enduring.

The first is a consistent fidelity to the facts. The book is rich in arresting examples of hard facts, often accompanied by numbers. We learn that Primo Levi’s Auschwitz memoir, If This Is a Man, was serially rejected, eventually published by a small local press in a tiny print run of 2,500 copies, few of which sold. Most were remaindered, stored in a Florence warehouse, and destroyed in the flood of 1966. What better illustration could there be of the immediate postwar lack of interest in survivors of the Shoah? Or take another example: the next time Maale Adumim is described as a West Bank settlement, consider that “this ‘settlement’ comprises more than thirty square miles—making it one and a half times the size of Manhattan…some ‘settlement.’”

Judt’s writing radiates scholarship: even his opponents could rarely challenge him on the facts. In his hands rigor was a weapon. The book includes a thorough demolition of Norman Davies’s Europe: A History (1996), leaving that book in shreds. But he draws only from an armory of facts, just one that happens to be better stocked than Davies’s. At the height of Bush-era Francophobia in the precincts of Republican Washington—when Paris was mocked as the capital of cheese-eating “surrender monkeys” and only “freedom fries” were allowed on the menu of the congressional canteen—Judt discharges a magazine full of facts:

In World War I, which the French fought from start to finish, France lost three times as many fighting men as America has lost in all its wars combined. In World War II, the French armies holding off the Germans in May–June 1940 suffered 124,000 dead and 200,000 wounded in six weeks, more than America did in Korea and Vietnam combined. Until Hitler brought the United States into the war against him in December 1941, Washington maintained correct diplomatic relations with the Nazi regime.

There is more to this than just a display of copious knowledge, though Judt certainly had that. It is a faith in evidence, a devout empiricism that agrees to be bound by the facts wherever they lead—even if that means shedding one’s own prejudices and letting go of one’s most fondly held beliefs. It’s what he demanded of Hobsbawm over communism and himself over Zionism. It is in fact close to an ideology in itself, this belief in a truth that can be excavated through serious, honest inquiry. And it partly explains why Judt placed so much weight on the notion of “good faith.”

The second factor comes close to a statement of the obvious. It is to note that though Judt was a commentator on contemporary politics and a writer of what is now called “long-form” journalism, his calling was as a historian. Of course that enriched his observations about the present, but there was more to it than that. He was also a champion of the past, insistent on learning from it and retaining from it what was worthwhile. That is the sentiment that powers the essay on social democracy, for example, as well as several others that turn a retrospective eye on the twentieth century as it ended. In the headlong rush into the future Judt saw his generation discarding much that its predecessors had carefully built and that was worth saving.

The result is, in more than a few places, a note of unexpected conservatism from this man of the left. “Bring back the Rails!” he cries in one essay. Another speaks of “The Wrecking Ball of Innovation.” Approaching his own death, and perhaps surprising himself as much as anyone else, he wrote, with the social democratic model in mind: “The Left, to be quite blunt about it, has something to conserve.”

The weight that Judt placed on memory brings us closer to the heart of his writings’ enduring value. Though able to speak of the grand, sweeping forces of history or geopolitics, he never lost sight of the centrality of people’s lived experience in shaping their ideas, attitudes, and longings. Not the facts on the ground, writes Homans, so much as the “‘facts inside’—the things that were just there, like furniture in [the] mind,” those things you might bump into without ever seeing or knowing them fully.

He applied that logic to his subjects, attributing Hobsbawm’s refusal fully to disavow Stalinism, for example, to the historian’s loyalty to his earlier “adolescent self,” the boy who had witnessed the Communists confront the Nazi brownshirts in pre-war Berlin. He applied it to nations, so that even when condemning contemporary Israelis’ blindness to the occupation, he could see that, thanks to the Jewish past, “in their own eyes they are still a small victim-community, defending themselves with restraint and reluctance against overwhelming odds.” And he applied it to himself, understanding how his own life story—from his childhood encounters with British anti-Semitism to the multiple identities of a British-Jewish historian of France living in Manhattan—might color his worldview. The result is a spirit of empathy that runs through his writings, a patience missing in those cursed with ideological certainty.

Yet that empathy should not be mistaken for moral relativism, indulging bad behavior as the understandable consequence of this or that experience. A fierce morality is present in Judt’s work, a clarity about right and wrong that leads back to the moral touchstone that is the Holocaust. Homans suggests that Jewishness was perhaps the most crucial of the “facts inside” Judt. She writes that the loss of a cousin, whose name was Toni, in Auschwitz acted as

a kind of black hole in his mind…weighty, incomprehensible, like evil or the devil, where this moment in history and this aspect of his Jewishness lay.

There is indeed—and this is the third factor in explaining his writings’ enduring value—a moral center to Judt’s work, the product perhaps of a weary knowledge of the wickedness of which humanity is capable. But it travels alongside a hope for something better and an understanding of the obstacles in our way. Judt wrote of his French hero: “Camus was a moralist who unhesitatingly distinguished good from evil but abstained from condemning human frailty.” That might be a fitting epitaph for Judt himself, whose wise, humane, and brave erudition this collection captures rather beautifully.