In 1619, at the ripe age of twenty, Gian Lorenzo Bernini set himself the seemingly impossible challenge of carving the human soul in marble. Two souls, in fact: a blessed soul bound for Heaven and a wicked soul newly damned to Hell, the most insubstantial of beings portrayed in solid stone from the neck up. These two remarkable images, preserved since the seventeenth century in the Spanish embassy in Rome, recently provided the focus for a small but choice exhibition at the Museo del Prado in Madrid.

The Blessed Soul is female, with a classical profile and a classical coiffure, crowned with a garland of roses frozen forever. Between her parted lips we can just detect a row of perfect teeth, a feat of detailing that the ancient Greeks and Romans regarded as proof of a consummate sculptor—and Bernini had no intention of lagging behind the ancients, or anyone else. The blessed soul’s eyes are carved with irises and pupils upturned toward her heavenly reward, like the pearly-skinned damsels that the painter Guido Reni was churning out at the same moment. In her perfection, the Blessed Soul lacks every trace of personality, but perhaps this is the point; she has been purified of every fault.

The Damned Soul, by contrast, is male, and unmistakably individual, from his definite features—heavy brow, corrugated forehead, a wisp of mustache—to his wild expression and his crazy flamelike hair, bristling with horror at what he sees before him. He is a self-portrait of Bernini, making faces in a mirror as he envisions the torments of Hell, and we can see not only his full set of rather sharp teeth but also his tongue, so highly polished that it seems realistically wet. To suggest the infernal flames reflected in the Damned Soul’s dark, intent eyes, Bernini has hollowed out their irises, leaving a pinpoint of white marble in the center of each to capture a fiery gleam.

In making his imaginative leap into the Inferno, the young artist may have used the Spiritual Exercises of Ignatius Loyola, where Hell appeared on the fifth day of the first week of a month-long discipline. Loyola sounded the depths of perdition by appealing to the five earthly senses, and so does Bernini’s marble head. Loyola writes:

First Point. The first Point will be to see with the sight of the imagination the great fires, and the souls as in bodies of fire.

Second Point. The second, to hear with the ears wailings, howlings, cries, blasphemies against Christ our Lord and against all His Saints.

Third Point. The third, to smell with the smell smoke, sulphur, dregs and putrid things.

Fourth Point. The fourth, to taste with the taste bitter things, like tears, sadness and the worm of conscience.

Fifth Point. The fifth, to touch with the touch; that is to say, how the fires touch and burn the souls.

The stench of sulphur and smoke visibly wrinkles the Damned Soul’s nose, making those mephitic vapors easier to imagine than the scent of the Blessed Soul’s crown of roses. Bernini seems to have no doubt about where he and his viewers will end their days.

The artist often served as his own model, especially in the early phases of his career. Some two years before carving these souls for the Spanish monsignor Pedro de Foix Montoya, he created a life-sized statue of Saint Lawrence (1617), his name-saint, who was put to death by roasting on a gridiron. To give the martyred deacon’s face a plausible sense of agony, the eighteen-year-old Gian Lorenzo reportedly thrust his own thigh into the fire while watching his face in a mirror (Lawrence himself, on the other hand, with saintly aplomb, was said to have joked, “Turn me over; I think I’m done on this side”). A large-as-life statue of David (1623–1624), loading the slingshot that will bring down Goliath, bites his lip with fierce concentration, as Bernini himself must have done so often when he picked up hammer and chisel, or sank his hands into a slab of clay. Like Saint Lawrence, David must have acted as a kind of alter ego for the young sculptor, a small, fierce man of singular charm who had a burning urge to create, and a colossal libido to match.

Like David, marksman, king, and poet, Gian Lorenzo Bernini was precocious, authoritative, and versatile: he had the touch no matter what he put his hand to. He could make limp swags of drapery swirl and throb as if some sort of lifeblood ran through them, like the corkscrew gyres of the cloak that twist around Apollo’s loins as he reaches for the nymph Daphne (1622–1624) and feels her skin turn to bark under his fingertips. Sculpted twenty-five years apart, Bernini’s two life-size images of saintly women in ecstasy, Saint Teresa of Avila (1645–1652; see illustration below) and Blessed Ludovica Albertoni (1671–1674), convey their passionate spiritual state by the agitation of their heavy clothing as well as the expressive, elusive hints of faces, hands, and feet.

Advertisement

Bernini’s tomb of Pope Alexander VII in St. Peter’s Basilica (1671–1678) shows a gilt bronze skeleton struggling to emerge from a dense shroud of mottled red marble: a human soul is struggling to break free of its carnal clothing, the flesh rendered as a literal curtain of meat. As simple an object as the black-and-yellow marble drape that clings improbably to a Gothic pillar in the Roman church of Santa Maria sopra Minerva, the tomb monument of a pious widow named Sister Maria Raggi (1647), still flutters after all these centuries in a secret celestial breeze.

For so small a man (the fingerprints preserved on his terra-cotta models are surprisingly tiny), Bernini exerted a titanic influence on the arts and the cityscape of seventeenth-century Rome, where he spent nearly the whole of his long life. His father, Pietro, was a Florentine sculptor who worked in Naples before settling in Rome with his growing family when Gian Lorenzo was eight. The elder Bernini modeled his own carving technique on Imperial Roman sculpture, with its copious drill work and high polish, but the son departed quickly from his father’s distinctive style, using rasp and chisel where Pietro drilled and polished. Already executing sculptural commissions as a teenager, Gian Lorenzo quickly branched out from sculpture into painting, architecture, theater, urban planning, and the vast universe of the decorative arts. Fiery and driven, he became all the greater as an artist because he was forced to compete for attention with stupendous rivals: Pietro da Cortona in painting and architecture, Alessandro Algardi in sculpture, and Francesco Borromini, the greatest—and most demanding—architect of them all.

The magnet that attracted all these talented souls was papal Rome. By the seventeenth century, thanks to the Protestant Reformation and the rise of Spain and France as nation-states, the city had lost political and religious significance. The papacy compensated for those losses by reinforcing Roman, and Catholic, dominion over the arts. For more than six decades, that dominion depended on the versatile hands and ruthless charm of Gian Lorenzo Bernini, whose skills, already from an early age, included the ability to run a large artistic workshop along with an impressive series of building sites, beginning with the perpetual work in progress of St. Peter’s Basilica. He was notoriously thrifty when it came to paying his subordinates, and several struck out on their own, none more loudly than Borromini, shocked to discover that he was earning one twentieth of the master’s salary.

The new exhibition “Barocco a Roma” at Palazzo Cipolla shows just how powerfully Rome proclaimed its status as a cultural capital in the middle years of the seventeenth century, through treasures that range from musical instruments like the famous Barberini Harp (the pride of Rome’s underused, underfunded, glorious Museum of Musical Instruments), to Borromini’s flawlessly precise drawings from Vienna’s Albertina collection, to a choice collection of Baroque paintings, to a marvelous little bronze Bernini lion on a porphyry base that was last seen in the Madrid exhibition; it’s a tabletop version, for the king of Spain, of the most beloved figure from the sculptor’s Fountain of the Four Rivers in Rome. The installation is superb, with a haunting series of Bernini portrait busts set at the visitor’s eye level.

Bernini may have hated making portraits of other people, but he did it supremely well. We can look right into the blandly impervious face of his great patron, Pope Urban VIII, newly elected and delighted at the prospect of his papacy (in a 1631 engraved portrait by Claude Mellan from a drawing by Bernini), and then we can see the haggard image of Urban ten years later, after his two tragic mistakes, the condemnation of his onetime friend Galileo Galilei and his futile war against the feudal stronghold of Castro, have blighted the final years of his reign. The sculptor lavished particular attention on a larger-than-life terra-cotta bust of Pope Alexander VII, a diplomat with a poet’s soul who counted as a true friend, and on the ardently intimate marble portrait bust of his mistress, Costanza, exhibited in “Barocco a Roma” with the traditional identification as Costanza Bonarelli.

However, thanks to a recent book, Bernini’s Beloved, by the art historian Sarah McPhee, we now know a good deal more about this young woman and her portrait, enough to change the way we might want to look at it. Bonarelli, for example, is her married name, and it was more usually written Bonucelli. Her maiden name was Piccolomini, a Sienese family that provided two Renaissance popes. Costanza, therefore, belonged to the nobility.

Advertisement

Thus the tousled hair and open blouse of this warmly intimate portrait are sexy, to be sure, but they are also a sign, as McPhee notes, of aristocratic sprezzatura rather than easy virtue: the equivalent of the haphazardly buttoned cassock we can see in Bernini’s portrait of Cardinal Scipione Borghese, a papal nephew, or the wispy, unkempt beard of Pope Innocent X (both works also on display at Palazzo Cipolla). These casual touches serve as signs that the sitter, and hence the portrait, are alive, moving, irregular. Bernini wants Costanza to look like a living, breathing person rather than an elaborate doll, like Giovanni Lazzoni’s bizarrely stylized portrait bust of her contemporary Olimpia Aldobrandini (a work of 1660 now in the Doria Pamphilj Gallery, Rome). Indeed, Bernini’s portrait of Costanza Piccolomini would transform the portrayal of women in Baroque Rome, inspiring Algardi, for example, to sculpt the fearsome dowager Donna Olimpia Maidalchini, Pope Innocent’s sister-in-law, with her widow’s weeds billowing behind her. If Costanza looks as if she is just about to speak, Donna Olimpia’s ominously pursed lips suggest that she has already spoken, striking fear into the hearts of every visitor to the Galleria Doria Pamphilj.

Costanza’s husband, Matteo Bonucelli, was a sculptor in the Bernini workshop, engaged, along with a vast team of fellow artists, in decorating the interior of St. Peter’s, where Luigi Bernini, Gian Lorenzo’s much younger brother, acted as general engineer and business manager. The marriage was childless; was it sexless too? No surviving records tell why Costanza was sleeping with her husband’s forty-year-old employer, though we know of other roughly contemporary cases in which a subordinate artist in a workshop “lent” an attractive wife to the master. From Bernini’s painted self-portraits (and his sculpted image as David) we know that he had the same kind of searing stare as Picasso (and Leonardo, and Titian), and we know what effect Picasso’s ardent eyes had on women. Gian Lorenzo Bernini may have been irresistible in similar ways. When he finally married, he sired eleven children—it seems safe to conclude that he liked sex at least as much as he liked carving marble.

But Costanza Piccolomini was also carrying on an affair with twenty-five-year-old Luigi Bernini, whose brilliance by all accounts came close to that of his eldest brother, without Gian Lorenzo’s driving ego and with all the advantages of youth. On a March day in 1638, about a year after immortalizing Costanza in marble, Gian Lorenzo, spying from a carriage, caught his brother coming out of the Bonucelli house behind St. Peter’s. In a sequence worthy of a Baroque action film, for the next hour or so the great artist went berserk. He chased Luigi into the basilica, beat him with an iron rod, cracking two of Luigi’s ribs, and then, rapier in hand, stabbing wildly, he began a headlong pursuit across the breadth of Baroque Rome. From the Vatican Gian Lorenzo harried the injured Luigi across the Tiber, past the banking district, past the Capitol, up the slopes of the Esquiline Hill to the basilica of Santa Maria Maggiore, the ancient church that rose across the street from the Bernini family home and where the family lies buried by the main altar.

Luigi knew that he was running for his life. He drew far enough ahead of Gian Lorenzo to slip into the basilica and pull its heavy doors behind him. Meanwhile, his frenzied brother, sword in hand, searched their house as Mamma Bernini looked on in horror—but no Luigi. Then, in his mother’s words, Gian Lorenzo, “with disdain for God, the Church, and its Masters,” crossed the street to Santa Maria Maggiore, kicking and pounding at the doors, trying desperately to beat them down. Only when his mother appeared on the scene did the fratricidal battle break up; she would later lament to the papal police that her eldest son acted “as if he were master of the world.”

Then, fury chilled to icy rationality, Gian Lorenzo turned his attentions to Costanza. Two hours after Luigi had left her house, one of the elder Bernini’s servants pulled up with two flasks of the white wine called greco; as she reached for the gift, the swift stroke of a razor slashed her face. This ritual disfigurement, called the sfregio, was normally reserved for wayward prostitutes, and in the days before antiseptics or antibiotics infection often introduced dreadful complications. The mark of even the most surgically inflicted sfregio lasted, of course, for the rest of the victim’s life, and there was no mistaking its meaning.

Costanza Piccolomini was twenty-five when her aristocratic face was marked as the face of a fallen woman. Had she taken up with the Bernini brothers for love, or money—at this point she and her husband had little enough of that—or boredom? All told, we know maddeningly little about this strange love quadrangle, three sculptors and a woman of twenty-five, except that it all ended in violence and tears. The wound to her face took weeks to heal; it must have been deep, possibly infected, a blow to her soul as much as to her countenance, but again, we know only the bare outline of the story. A doctor was still caring for her a month after the attack.

Furthermore, because she had been caught in flagrant adultery, albeit by yet another adulterous partner who was not her husband, Costanza was as liable to criminal charges as Bernini, and here the record is ample. The penalties for their respective crimes, assault and adultery, were surprisingly similar in their harshness, but Bernini, at least, had the protection of a pope. His servant was condemned to exile as the material perpetrator of the crime, and Bernini was fined three thousand scudi, a penalty commuted by Urban VIII.

Costanza spent several months in a convent for penitent prostitutes before returning to her husband, who took her back and made a decent life with her; in his will he would call her “my beloved wife.” In later years, she became one of Rome’s most successful art dealers, working out of her house on what is now called the Vicolo Scanderbeg, just beneath the Quirinal Palace where the president of Italy resides. In her mid-thirties, she bore a daughter, probably fathered by a high-placed prelate, whom she brought up and who married well. McPhee has tentatively identified two later painted portraits of her, a dignified widow with her facial scar tactfully omitted.

In Baroque Rome, evidently, art, as a matter of honor and reputation, could easily become a matter of life and death. Seventeenth-century Roman police records are filled with the names of painters, sculptors, and architects accused of slander, assault, rape, and, often enough, murder. Caravaggio famously skewered a local thug (Ranuccio Tommasoni, the forerunner of a mafioso) on a Roman tennis court, but the police also booked the painter for writing scurrilous verse, throwing artichokes, and ogling schoolchildren. When Francesco Borromini discovered that one of his workmen was vandalizing marble for the restoration of the Lateran Basilica, he ordered his foreman to beat the culprit; when the man died, Borromini was charged with murder. Both Caravaggio and Borromini were actually sent into exile, Borromini for a year, Caravaggio for life, though a pardon seems to have been on its way when he collapsed and died along Tuscany’s sultry mosquito coast.

Bernini, on the other hand, because of his charm and his position in the Roman art world, escaped punishment. For similar reasons, after about a year, Gian Lorenzo was compelled to forgive the randy Luigi; he depended on his brother’s skills as an engineer and business manager. The incident had at least two lasting consequences on Bernini’s life: the following year, by order of the pope and his own mother he married a twenty-one-year-old girl of good family and blameless reputation, and for the rest of his life he was racked by spiritual struggles with the ideas of Christian guilt and atonement. Saint Lawrence roasting on the grill and the Damned Soul were only the starting points of Gian Lorenzo Bernini’s spiritual journey through Heaven and Hell.

Among the visions of Heaven that Bernini supplied to the churchgoers of Baroque Rome, none is more impressive than his work inside St. Peter’s, from the Baldacchino, the bronze canopy that stands beneath the basilica’s gigantic dome, to the monumental Cathedra Petri, the Throne of Saint Peter. This sits within a glory of gilded bronze, pierced by a golden-glazed window and populated by legions of the winged babies called spiritelli, “little spirits.” The relics of the Throne of Saint Peter are clad in black bronze and held aloft by four Doctors of the Church, Saints Augustine, Ambrose, John Chrysostom, and Athanasius, their black bronze skin contrasting with their golden robes.

Bernini at St. Peter’s: The Pilgrimage is a beautifully illustrated collection of essays by the distinguished art historian Irving Lavin, who has spent nearly as much time studying Bernini as Bernini once spent decorating St. Peter’s. Despite the immensity of the building itself (the dome can be seen distinctly on the horizon from as far away as the Villa d’Este in Tivoli), Lavin insists that the true measure of Bernini’s artistry can be taken only by studying the details, to which he has paid meticulous, appreciative attention, as well as the majestic ensembles that have misled generations of visitors into thinking that St. Peter’s is the mother church of Christendom (that honor goes to the Lateran Basilica across the river on the other side of town).

As a doctoral student, Irving Lavin made a pioneering study of the terra-cotta models that were such an important part of Bernini’s working method, and a choice selection of these, by Bernini himself, by his assistants, and by his rivals, has been gathered in one room of the “Barocco a Roma” exhibition. The best guide to understanding these works and their place in the great sculptor’s artistic life is Bernini: Sculpting in Clay, the catalog of a recent exhibition at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York. Here Anthony Sigel, curator of sculpture at Harvard’s Fogg Museum (which has its own impressive set of Bernini terra-cottas), provides a detailed list of Gian Lorenzo’s sculptural techniques, but for any viewer the most moving aspect of terra-cotta will be the way it preserves traces of the artist’s touch, in smears and swipes of the fingers, in the imprints of his nails and his surprisingly slender fingertips. As long as these exist, it is hard to maintain that Bernini is dead.

To keep his volcanic soul out of Hell, the elderly Gian Lorenzo became devoted to a particular idea of redemption from sin: the blood of Christ. By way of assisting his meditations, he created a peculiar little painting of an airborne crucifix dripping torrents of liquid from wounded hands and feet into a vermilion sea, as a levitating Virgin Mary collects the blood and lymph gushing from her son’s side into two chalices. It is a disconcerting image, painted in the aftermath of a decades-long conflict between Catholics and Protestants in Europe (officially known as the Thirty Years’ War of 1618–1648, but a war that really began fifty years earlier) and focused obsessively on the physical immediacy of that blood-red sea.

The world into which Gian Lorenzo Bernini brought his glorious visions was a harsh, violent world—to whose violence he had made his own contribution—but the effect of his work has been to bring people together, not only in his own time and place, but also in our own time, in the Rome of Pope Francis, whose native Argentina is commemorated on yet another of Bernini’s creations, the Fountain of the Four Rivers in Rome’s Piazza Navona, where the figure representing the Rio de la Plata, symbolizing the Americas, shrinks back in awe at a golden bolt of sunlight that has pierced the mountain on which he perches (the metal of the bolt is long gone, but the traces survive). Roman legend says that his more immediate fear is for the Borromini façade of the church of Sant’Agnese in Agone in front of him, and whether it will topple into the square.

This Issue

June 4, 2015

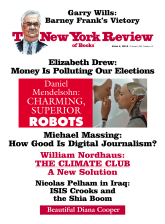

Barney Frank’s Victory

The Climate Club