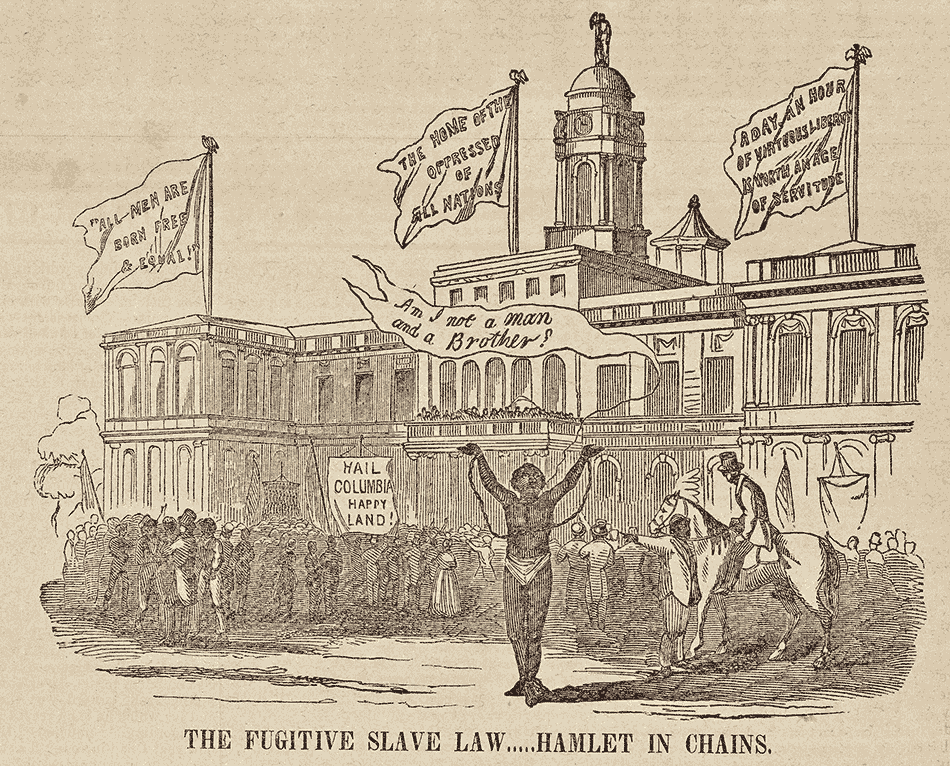

Rare Books and Manuscripts Library, Columbia University

James Hamlet, the first person returned to slavery under the Fugitive Slave Law of 1850, in front of city hall in New York; engraving from the National Anti-Slavery Standard, October 17, 1850. Hamlet was returned by force to Baltimore, but ‘by the time this appeared in print,’ Eric Foner writes in Gateway to Freedom, ‘New Yorkers had raised the money to purchase Hamlet’s freedom and he was back in the city.’

When the Constitutional Convention met at Philadelphia in 1787, slavery was on the way out in most states north of the Mason-Dixon Line. The bifurcation between slave and free states that would plague the nation for the next seventy-five years and bring civil war in 1861 had already begun. Many slaves had sought freedom by trying to run away. By 1787 they could run to states where slavery no longer existed or would soon disappear. Delegates to the Philadelphia convention from southern states therefore demanded a guarantee for the return of fugitive slaves as the price for approval of the new Constitution. They got what they wanted in Article IV, Section 2: “No person held to service or labour in one state…escaping into another, shall…be discharged from such service or labour, but shall be delivered up on claim of the party to whom such service may be due.”

In the typical circumlocution of the Constitution, in which the word “slavery” does not appear until the institution was abolished by the Thirteenth Amendment in 1865, this article was a major concession to slave owners. “We have obtained a right to recover our slaves in whatever part of America they may take refuge,” declared Charles C. Pinckney of South Carolina, “which is a right we had not before.”

But this fugitive slave clause did not enforce itself. Who would be responsible for apprehending escapees to free states and returning them to slave states? In 1793 Congress addressed this question with a law stipulating that a slave owner or his agent could capture a runaway and take him before any judge or magistrate to claim him as a slave, with nothing more than an affidavit from a slave-state judge or even the owner’s word as evidence. If the magistrate accepted this evidence, he would issue a certificate of removal and the owner would get back his property. This law made the capture of alleged fugitives the responsibility of the owners, not the state or federal governments. But it also made free blacks living in the North vulnerable to kidnapping and enslavement, with the collusion of corrupt magistrates.

During the first four decades of the nation’s history under the Constitution, neither the escapes of slaves nor the kidnappings of free blacks rose to the level of a national political issue. Several northern states passed anti-kidnapping or “personal liberty” laws to provide some legal safeguards for alleged fugitives. With the advent of a militant abolitionist movement in the 1830s and a reactive proslavery counterattack, however, the issue of slavery became central to national political life. Although antislavery societies, lecturers, and newspapers multiplied in the 1830s, bondage in the South remained an abstract issue to most northern whites. But a runaway slave staking his life on a break for freedom turned slavery from an abstraction into a flesh-and-blood reality. The antislavery press publicized heroic escapes by fugitives who outwitted the bloodhounds and followed the North Star to freedom. Escaped slaves, most notably Frederick Douglass, became the most effective antislavery lecturers. The flight of Eliza across ice floes in the Ohio River with her child in her arms in Uncle Tom’s Cabin became one of the most unforgettable images in antebellum literature.

Antislavery societies were the first major interracial organizations in America. White men and women occupied most of the leadership posts. But black people took the lead in forming “vigilance committees” as auxiliaries to the societies in several northern cities. These committees had the dual purposes of protecting free blacks from kidnapping and of aiding fugitive slaves on their way to freedom. The first activity was open and public: efforts to get the police to arrest kidnappers, cases taken to court by sympathetic white lawyers acting pro bono, attempts to recapture kidnapped victims. The second activity was often secret: safe houses for escapees along their route to freedom, financial aid, assistance to fugitives in finding a job or a place to live in the North or in Canada.

From these latter actions grew what came to be called the underground railroad, a term that originated in the late 1830s (when real railroads with locomotives and iron rails were rapidly expanding) to describe these clandestine routes to freedom. The underground railroad was never the tightly organized and large-scale operation with hundreds of “stations” and “conductors” that many northern whites later remembered as part of their heroic youth. Rather, it was a loosely affiliated group of local vigilance committees and other antislavery activists or sympathizers whose numbers and activities ebbed and flowed over the years.

Advertisement

The underground railroad ran mostly through the free states, but also extended into the border slave states of Maryland, Delaware, Virginia, Kentucky, and Missouri, from which nearly all of the escaped slaves fled. In these slave states a few sympathetic whites like the Quaker Thomas Garrett in Wilmington, Delaware, or the ship captain Albert Fountain in Norfolk, Virginia, helped hundreds of slaves to escape. But initial aid to the runaways came mainly from fellow slaves or free blacks. When they reached a northern town or city, fugitives usually found their first support among the black community and from black “agents” of vigilance committees like William Still in Philadelphia and David Ruggles or Charles Ray in New York. White supporters, especially Quakers, were vital cogs in this enterprise as the fugitives moved to greater safety from recapture farther north, sometimes all the way to Canada.

No one knows how many slaves escaped to freedom on the underground railroad. Estimates range from a thousand to a few thousand per year from 1830 to 1860. Whatever the number, it was only a tiny proportion of the slave population that reached four million by 1860. Yet as Eric Foner points out in his splendid book, Gateway to Freedom, the incidence of escaping slaves and northern assistance to them was “sufficient to become a cause of alarm in the slave states and of contention between North and South.” The slaves who ran away and thousands who tried but never made it “gave the lie to proslavery propaganda” that slaves were contented with their status.

Southern demands for enforcement of the Constitution, especially after passage of a draconian new Fugitive Slave Law in 1850 by mostly southern votes in Congress, “reinforced abolitionists’ claim that the Slave Power reached into the North…a source of deep resentment in much of the North.” In their secession ordinances in 1860–1861, several southern states cited the North’s resistance to the Fugitive Slave Law as a reason for leaving the Union. “All in all,” writes Foner, “the fugitive slave issue played a crucial role in bringing about the Civil War.”

Foner is one of our foremost historians of the Civil War and Reconstruction era. His earlier work contains several references to the fugitive slave issue but no systematic study of it. He was inspired to write this book by one of his undergraduate students, Madeline Lewis, who wrote her senior thesis at Columbia University on Sydney Howard Gay, a white abolitionist whose papers are at Columbia. Gay was editor of the National Anti-Slavery Standard in the 1840s and 1850s, the weekly newspaper of the American Anti-Slavery Society published in New York City. Gay was also in charge of a committee operating from the newspaper office that aided fugitive slaves in transit through the city on their way to points north. In 1855–1856 he kept a detailed record of the fugitive slaves he and his assistant, a black man with the imposing name of Louis Napoleon, harbored and protected while they were in the city. Lewis called Foner’s attention to Gay’s journal, which he had titled “Record of Fugitives.” “I found the Record of Fugitives so riveting,” writes Foner, “that it led me to embark on the research project that resulted in this book.”

We can be glad that it did. There is a large literature on the underground railroad, starting with the post–Civil War generation that celebrated these (mostly white) heroes of freedom, down to a later contingent of historians who emphasized the slaves’ own active part in their escapes to freedom and debunked the notion of an organized network of sympathetic whites. Such studies culminated in recent years with a more balanced appraisal of a genuine interracial effort to aid fugitives. Gateway to Freedom falls into this last category. It is really two books skillfully melded into one. The first is a general history of the fugitive slave issue and of the underground railroad in a national setting. The second is a specific focus on New York City as a nexus of the underground railroad in the mid-Atlantic region. This is the “hidden history” indicated by the subtitle.

Most studies of the underground railroad emphasize the routes from Kentucky across the Ohio River into the Midwest and Canada, or the transit from Maryland and Delaware to Philadelphia and on to New England, upstate New York, and Canada. New York City figures little if at all in these accounts. There is a reason for that: New York’s connections of trade and finance with the South, its large immigrant population unfriendly to African-Americans, and its Democratic Party machine created a hostile environment for fugitive slaves. Kidnapping gangs made the city dangerous for free blacks. Even though the American Anti-Slavery Society and its newspaper were headquartered in the city, antiabolitionism was much stronger than antislavery sentiment there.

Advertisement

Yet as the country’s largest port and the gateway to the interior of the state and to New England, New York City was a principal transit hub for fugitive slaves on their way to somewhere else. As Foner discovered in his study of Sydney Howard Gay’s Record of Fugitives, 214 runaways were aided by Gay and Louis Napoleon in 1855–1856. The local vigilance committee helped scores of others in the same period. During the preceding two decades, these and other organizations helped hundreds, perhaps thousands.

Few escapees remained in the city; many continued north to Syracuse, which became a sort of Mecca for fugitive slaves—in part because of its accessibility to Canada, where many fugitives fled after passage of the 1850 Fugitive Slave Law made it dangerous to remain even in the friendly environs of upstate New York. Altogether, Foner estimates that “between 3,000 and 4,000 fugitive slaves may have received assistance while passing through” New York City from 1835 to 1860. But until now that history had indeed remained hidden.

Gay’s Record of Fugitives enables Foner to analyze the sample of 214 runaways, whose characteristics may have been fairly representative of those who escaped from the eastern slave states. Half of them came from Maryland and Delaware, and almost one third from Virginia. The other states represented were both Carolinas, Kentucky, and Georgia plus the District of Columbia. Those from the Carolinas and Georgia, and some from Virginia, stowed away on coastal schooners with the collusion of black crewmen or, in a few cases, sympathetic captains like Albert Fountain who were willing to take considerable risks—for a fee—to carry the fugitives.

Most of the slaves were funneled through Baltimore, Wilmington, and/or Philadelphia before arriving in New York, where Gay or Louis Napoleon met them at the docks (including the ferry dock from Jersey City). Many had escaped by foot, some had stolen a carriage, a few had come by a real aboveground railroad. Some came as individuals, but most had traveled in small groups, often including family members. Twenty-nine of the 214 were children; of the adults, three fourths were men, average age twenty-five and a half. The most common reason for running away was cruel treatment, including whippings. The next most frequent reason was fear of being sold. Some ran away to rejoin family members who had escaped earlier. After placing them temporarily in safe houses, Gay provided them with new identities as free blacks and sent them up the Hudson River by boat or by rail to Albany, Syracuse, and ultimately to Canada.

The Fugitive Slave Law of 1850 forced many blacks who had lived in the North for years, as well as recent fugitives, to migrate to Canada because of the license that the law seemed to grant to bounty hunters. In 1842 the Supreme Court had issued a ruling in Prigg v. Pennsylvania that set in train a series of events that led to the 1850 law. The case concerned a Maryland slave owner convicted in Pennsylvania of kidnapping after he had forcibly brought back his runaway slave to Maryland. The Court overturned the conviction and declared the Pennsylvania antikidnapping statute unconstitutional. But the decision also stated that enforcement of the Constitution’s fugitive slave clause was entirely a federal responsibility.

This ruling opened the way to a series of new personal liberty laws by which several northern states prohibited their officials from helping to recapture escapees and forbade the use of state or local jails to hold fugitives pending a decision on their return. These laws provoked southern demands for a new federal statute to put teeth into the fugitive slave clause—an ironic commentary on the supposed southern commitment to states’ rights.

The resulting law in 1850 created a category of US commissioners who were empowered to issue warrants for the arrest and return of runaways to slavery. It allowed an affidavit by the claimant to be sufficient evidence of ownership and denied the fugitive the right to testify in his own behalf. The commissioner would earn a fee of ten dollars if he found for the claimant but only five dollars if he released the fugitive. Supposedly justified by the greater amount of paperwork if the escapee was returned, this provision produced the cynical comment that it fixed the price of a prime slave at a thousand dollars and the price of a Yankee soul at five. The commissioners could deputize any citizen to serve in a posse to aid enforcement of the law, and the law established stiff fines or a jail sentence for anyone who refused such orders or resisted the law. Efforts by northern congressmen to mandate a jury trial for fugitives were defeated.

This law not only drove thousands of northern blacks to Canada; it also provoked thousands of northern whites into defiance. New vigilance committees sprang up and existing ones were revitalized. Many northerners echoed the statement by the onetime fugitive slave Frederick Douglass that the best way to make the Fugitive Slave Law a dead letter was “to make half a dozen or more dead kidnappers.”

Several spectacular rescues or attempted rescues of escapees took place during the sectional conflict in the 1850s. In December 1850 the Boston Vigilance Committee spirited away two famous fugitives, William and Ellen Craft, from under the nose of a Georgia agent who had come to reclaim them. Two months later a black waiter, who used the name Shadrach Minkins, was arrested in Boston as a fugitive. While he was being held in the federal courthouse, a crowd of black men burst through the door and snatched him away before the astonished deputy marshal could stop them. In April 1851 the government managed to foil another attempt in Boston to rescue a fugitive, Thomas Sims, only by guarding him with three hundred soldiers who took him away at four o’clock in the morning for shipment South.

In September 1851 a group of black men in the Quaker community of Christiana, Pennsylvania, shot it out with a Maryland slaveholder and his allies who had come to arrest two runaways. The slave owner was killed and his son severely wounded in the affray. The following month a group of black and white abolitionists broke into a Syracuse police station, carried off the arrested fugitive William McHenry (alias Jerry), and sent him across Lake Ontario to Canada.

The federal government indicted several dozen men involved in the Shadrach, Christiana, and McHenry rescues. But with the exception of one man convicted in the McHenry case, all the defendants were acquitted or released after mistrials by hung juries. These outcomes infuriated proslavery southerners and generated a determination by the Franklin Pierce administration to make an example in the Anthony Burns affair in 1854, the next high-profile fugitive confrontation.

Burns was a Virginia slave who had escaped to Boston and gone to work in a clothing store, where southern agents suddenly seized him on May 24. News of the arrest spread quickly. The vigilance committee organized mass rallies; antislavery protesters poured into Boston from surrounding areas; black and white abolitionists mounted an assault on the federal courthouse that killed one of the deputies guarding Burns but failed to rescue him. The government federalized local militia and sent in army troops and marines. They marched Burns to the harbor, where a ship waited to carry him back to Virginia while tens of thousands of bitter Yankees looked on under American flags flown upside down and bells tolled the death of liberty in the cradle of the American Revolution.

It is almost impossible to exaggerate the impact of this event. The conservative Whig Edward Everett, who had previously counseled obedience to the law, declared that “a change has taken place in this community within three weeks such as the 30 preceding years had not produced.” And the textile magnate Amos A. Lawrence said that “we went to bed one night old fashioned, conservative, Compromise Union Whigs & waked up stark mad Abolitionists.”*

After chronicling these events, Foner notes that “nothing remotely like these confrontations occurred in New York City.” The cultural and political atmosphere there forced Gay, Napoleon, and their colleagues to continue operating without getting public attention. But operate they did, and Foner estimates that “despite the new federal law, over 1,000 fugitive slaves passed through New York City in the 1850s, aided by the underground railroad on their journey to freedom.” Many of these fugitives, including scores from Canada, returned south several years later as soldiers in the Union army to help win freedom for all of their lineage and to put an end to the Fugitive Slave Law forever.

-

*

The Fugitive Slave Law and Anthony Burns: A Problem in Law Enforcement, edited by Jane H. and William H. Pease (Lippincott, 1975), pp. 43 and 51. ↩