At times, when the fifty-six-year-old artist Peter Doig’s name comes up in certain art world circles—a world of curators, critics, and socially responsible artists who advanced on a steady diet of Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari and the bitter milk of anti–“patriarchal privilege”—there’s a great hue and cry. To begin with Doig is a patriarch—he’s the father of five, white, and not dead—whose grand ambitions, and interest in beauty and scale, have next to nothing to do with fashion, political or otherwise.

Still, there are complications of Doig’s biography that continue to stymie outright condemnation by some members of the museum world and others in the pleasure police. There are, for instance, Doig’s relationships to any number of pre- and post-AIDS-era gay men who enriched his life and he theirs. (As a young artist then living in London—he graduated from St. Martin’s School of Art in 1983—Doig appeared in an early Derek Jarman film, and continues to champion the work of the openly gay English painter David Harrison, among others.) There were, too, Doig’s early and later years in Trinidad and his paintings that included black figures and his StudioFilmClub, a weekly event Doig started in 2003, and that, until recently, screened independent movies made in the Caribbean and elsewhere. He has said of this enterprise:

Early on, we used to talk about…what’s a good film for here? But then after a while we just thought, Maybe that’s patronizing. Why shouldn’t people be able to see a film that’s not necessarily about their experience, even as metaphor; about something completely different.

Some of the critics, still dissatisfied by Doig’s credentials or what one might in a pinch call his humanism, raised a question about his alleged lack of sincerity—his supposed tricksterism—when it came to the world in which he put those black bodies. Was he not indulging the privilege of the colonialist when he painted Trinidad, a “third-world” country, with the lushness of an observer who was, so it was said, more interested in “exoticism” than the truth? Was Doig not, in his style and artistry, drawing a curtain between the spectator and the misery of the world? So doing, was Doig not cheating the viewer of the misery of that “other” world?

To see Doig’s show at the modestly designed Louisiana Museum of Modern Art near Copenhagen some days after an exhibition of his new work at the Palazzetto Tito in Venice—his first one-man show in Italy—is to be reminded of how crucial installation is to our understanding of an artist’s work. While the Louisiana show is larger and contains dozens of works made over a nearly-fifteen-year period, I think the curators’ slightly academic, straightforward approach feels right. Arranged not so much chronologically as by association—landscapes with landscapes, the more architecturally focused pieces with buildings, and so on—the curators don’t interfere with the paintings, which speak for themselves. Or don’t speak. Doig’s work—sometimes painted in oil or distemper, on canvas or linen—is, despite its great narrative pull, purely visual in its approach.

Opening the Louisiana show is Doig’s ironic 100 Years Ago (Carrera) (2001)—a title that refers to how long cinema had been available in Trinidad. In this large-scale work we see the world divided into three primary strips of color and activity. The central strip in the canvas shows a bearded man sitting in a red-orange canoe; man and canoe are still on a still body of water. The sky above is dark blue and the sea a lighter blue; a green island or land mass floats in the distance. While this may feel too much like “let’s-take-a-journey-together” curatorially, it’s perfect for introducing the viewer to some of Doig’s themes, certainly at that point in his career.

Among these themes are his interest in figures existing in isolation, as exemplified by masters like Matisse and Daumier, and how that isolation draws the eye to the “different,” sometimes black figures in his work. (Doig sometimes uses photography in his work and the lone figure in 100 Years Ago was in part inspired by the band member he saw sitting in a canoe in a picture of the Allman Brothers.)

Unlike a number of his contemporaries who, it seems, deal with aesthetic theory first and then make art to fit it—the politically motivated, Belgian-born artist Luc Tuymans, for instance, comes to mind—Doig’s use of paint is the story he means to tell, the activity he wants to describe. In large, commanding works like Black Curtain (Towards Monkey Island) (2004), Doig combines his two brushstrokes: the thin application of paint, sometimes letting it drip in a modernist, color-field-painting- inspired way, but not before building up the surface underneath so those drips have something solid to slide against.

Advertisement

The paintings at the Louisiana are sizable, some as large as twelve feet wide, and that’s another problem for some of Doig’s detractors—their scale is yet another example of a white man taking up too much space. But the paintings are substantial. The painter’s relationship to the content—all that world filled with difference—is emotional without being didactic, an expanse of feeling that is more nakedly displayed in the Venice show, where the mystery of the artist’s self connects with the mystery of love.

Doig’s family moved from Scotland to Trinidad two years after his birth. (The artist’s father worked for an import-export firm.) As creoles—white persons living in the Caribbean—the Doigs were privileged and cut off. The Saint Lucia–born poet Derek Walcott captures something of that isolation in the images that make up his poem “Jean Rhys”:

In their faint photographs

mottled with chemicals,

like the left hand of some spinster aunt,

they have drifted to the edge

of verandas in Whistlerian

white, their jungle turned tea-brown—

even its spiked palms—

their features pale,

to be penciled in:

bone-collared gentlemen

with spiked mustaches

and their wives embayed in the wickerwork

armchairs, all looking colored

from the distance of a century

beginning to groan sideways from the axe stroke!

Trinidad and the axe stroke of time, history: owned by the French, owned by the Spanish, conquered by the English, with its independence “won” in 1962, its citizens joined by mixed blood, and the blood of conquest and survival. It’s an island that has its share of death and therefore memories and one sees that in Doig’s unforgettable 2004 painting, Lapeyrouse Wall. In it, a man of color walks past downtown Trinidad’s graveyard. He is shielding himself from the sun with an umbrella and the shapes on the umbrella mirror the corrosion on the wall. It’s not a painting about life in the midst of death. It’s more about shadows—life trying to withstand those elements that make Trinidad beautiful to vacationers looking for a bit of sun and difference, but something the body and thus consciousness must adapt to if one is a “native.”

In her 1988 book A Small Place, the Antiguan-born writer Jamaica Kincaid wrote:

That the native does not like the tourist is not hard to explain…. Every native everywhere lives a life of overwhelming and crushing banality and boredom and desperation and depression, and every deed, good and bad, is an attempt to forget this.

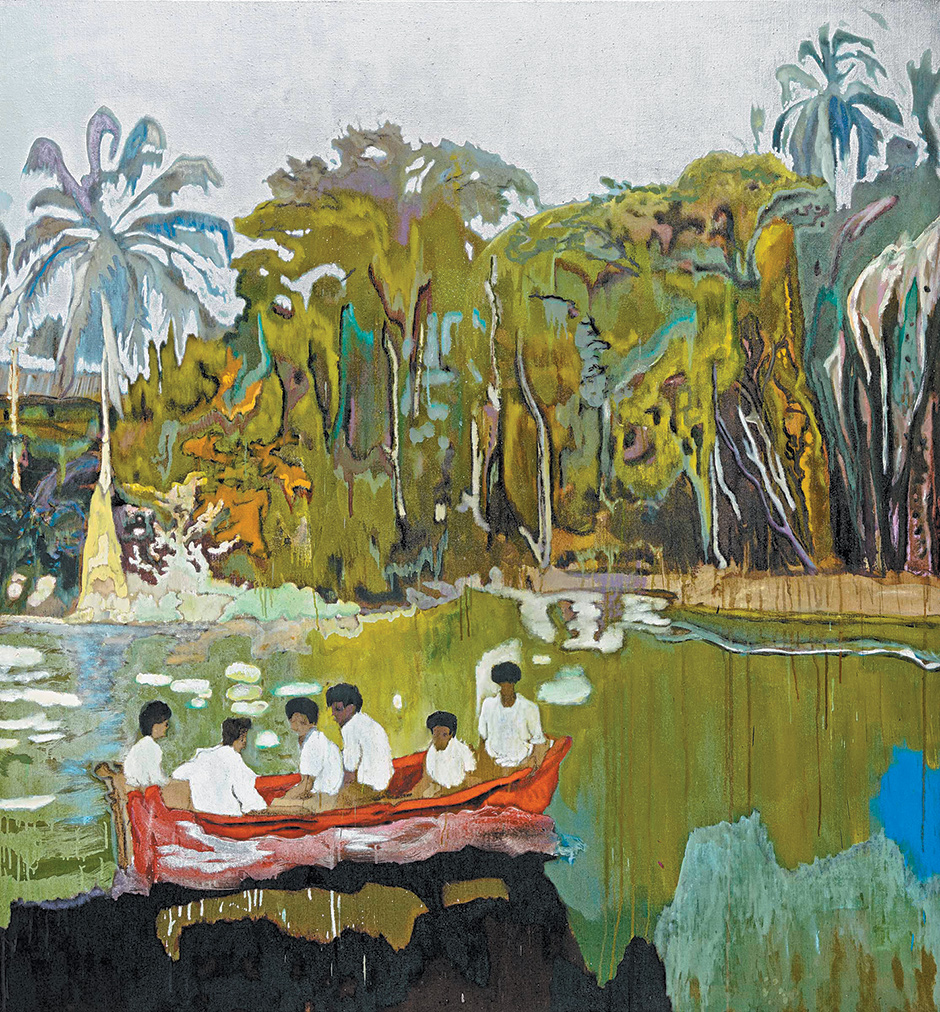

As a nonnative, Doig, whose family moved on to Canada when he was seven, works as a kind of cultural reporter—the sort of artist who makes culture in the place he lives because he is not born to the culture. (In this way he is very distinct from one of his more obvious influences, the British artist Michael Andrews, whose images describe the subconscious, too, but without the reportorial curiosity Doig brings to them.) This is the source, I think, of his freedom, which, in turn, feeds his imagination. He can “be” his subjects, but not really: he is quite apart from their citizenship, the unselfconscious ease that comes with being from somewhere, being something. His interest in difference doesn’t make him a colonialist, it makes him interested. In Red Boat (Imaginary Boys) (2004), Doig’s black figures are dressed in white shirts and they sit, like the man in 100 Years, in a body of water that could easily claim them—the boat could tip over—but they are too engaged in looking back at the viewer, which is to say Doig, who didn’t stop looking at them once he made the picture (see illustration from the catalog on page 60).

A couple of years after Red Boat, Doig painted another group of boys in a red boat—Figures in a Red Boat (2005–2007)—and they’re wearing white shirts, too, but we see them from a different vantage point, less far away, rendered with less intensity or a different kind of intensity. In that picture the boys are white, and painted on linen—a highly difficult surface to control (ask any color field painter). What can the subject’s race mean in either image and to either image? Can race be reducible to being different kinds of paint color? How does paint become—or not become—politically charged?

In 2000 Doig collaborated on a series of small paintings with the artist Chris Ofili that showed two figures: a black man with an enormous Afro and a white man dressed in a Napoleon hat and uniform. The ease of the pieces—their lovely jokiness—has a fair amount to do with the fun of fancy dress, and costuming as just another aspect of character, and how characters are interesting because of their fakery. The black figure is not more or less than the white figure; each is dressed according to his custom, his habits, the places where he belongs.

Advertisement

When I saw the Doig and Ofili pieces I was reminded of John Berger’s exceptional book Ways of Seeing (1973). In it the British-born art historian and novelist—one of the first to talk about race in painting—describes a seventeenth-century painting by Emanuel de Witte, Admiral De Ruyter in the Castle of Elmina. It shows a European man of wealth and position standing over a black slave who kneels before him; the slave is holding up a painting that depicts a castle that stands above one of the principal centers of the slave trade.

The black slave is reflecting the admiral’s wealth and conquest back to him, just as Prospero used Caliban to reflect himself, while gaining control of the latter’s island. In this painting and Holbein’s The Ambassadors (1497–1543) Berger writes about conquest and art:

What we are concerned with here is a stance towards the world; and this was general to a whole class. The two ambassadors belonged to a class who were convinced that the world was there to furnish their residence in it.

If Doig is part of the European tradition in painting—and he is—what exempts him from putting his residence in it first? A big difference is that in Doig’s world none of the characters live much in solid space; that is, they’re obscured by a natural setting that changes the surface of the painting, not to mention the world, as in the snow falling in Blotter (1993) or the watery setting surrounding the figure in Sea Moss (2004). Doig watches the atmosphere, the elements, in order to see how we protect ourselves against them, or adapt to them; either way, nature changes how we stand, sit, look. Weather also reflects how we think.

In major paintings like Blotter and Reflection (What Does Your Soul Look Like) (1996), the presumably male characters—in the former bundled against the cold while we can see only the feet and legs of the one in the latter—look down at pools of water. Moments before, the water’s surface had, it seems, been disturbed, probably by the subject. (Not unlike Jesus, the figures can walk across water, but in their case only because it’s shallow, just as a painting’s surface can appear to be shallow, too, until you spend time looking at it.) This drama acted out between man and nature is further disturbed by paint. Doig’s lines and carefully controlled drips bring to mind the scratches on the opening moments of a film which, in turn, evoke the artificiality of the movie being watched, and the real world of dreams they inspire. (In a 2012 interview Doig said: “I think my paintings, certainly, are filmic. I mean, how could they not be? You can’t get away from it; it permeates things.”)

While Doig’s figures and shapes like boats or a badminton table or rundown sagging houses (he says he likes painting “homely” houses to make “homely” paintings) are central to the frame, they don’t leave the eye once you get to the canvas’s edges; rather they become part of the painting’s continuum—the moments that will precede this moment, and the next.

When he was an art student in London, Doig worked as a dresser in the West End; he is not unfamiliar with the actor as himself, then becoming someone else, and then becoming himself again: transformation is at the heart of alchemy. So, too, with Doig’s paintings: his work is always in the act of becoming; the moments he captures—snow falling and nearly blotting out the scene in Cobourg 3+1 More (1994), or a skier flying high over the heads of other skiers in Olin MK IV (1995)—are transitional; life will be entirely different, at least visually, once that skier lands, the snow stops falling, and all that wonder becomes mundane again, ordinary, but maybe not in the mind.

Spectators are shaped by their epoch as much as artists are. Growing up in New York in the late 1970s and early 1980s helped form how I looked at all sorts of work—and what I looked for. While I found many things to learn from and admire at the Museum of Modern Art and the Metropolitan Museum—Robert Rauschenberg’s Monogram (1955–1959) at MoMA and Jean Auguste Dominique Ingres’s portrait of Princesse de Broglie (1851–1853) hanging in one of the Met’s great halls had an enormous effect on my thinking about collage and portraiture—established institutions did not interest me as much as exhibition spaces that felt more alive with becoming like the city itself. Still, the Princesse was as fascinating to me as SAMO, the downtown graffiti duo who made images out of words.

During that post-Vietnam era, manufacturers were abandoning the US for cheaper labor abroad. The money the famously liberal city had borrowed from the federal government couldn’t be repaid; there was debt and more debt. As Christopher Lasch pointed out in The Culture of Narcissism (1978), “Those who recently dreamed of world power now despair of governing the city of New York.”

In any case, the artists I admired couldn’t be governed; truth was their shared aesthetic. As a teenager I’d taken the A train from my home in the Bedford-Stuyvesant section of Brooklyn to check out the Studio Museum in Harlem. Founded in 1968 by a number of black artists, activists, and philanthropists who felt artists of color were unrecognized or underrecognized by museums and galleries downtown, the institution was, for me, part of a mosaic or panorama that included Fashion Moda in the South Bronx. Organized by the Austrian-born artist and curator Stefan Eins in 1978, the space promoted collaboration. (For example, inspired by Eins, Jenny Holzer made work with the Ecuador-born graffiti artist Lady Pink.)

At Fashion Moda one could see John Ahearn’s soulful, semiheroic sculptures, some of them life casts, of the citizens—all those children of immigrants, all those children of junkies—of that devastated place. And it was there, too, that one could hear the music and see the style that would lead, say, to contemporary music’s Rihanna on the red carpet, hip-hop savvy, ghetto fabulous, assured.

Even though the three pivotal exhibitions I saw took place sometime after the city blacked out in July 1977, and Son of Sam was behind bars, I still associate “The Real Estate Show” (1979), “The Times Square Show” (1980), and “New York/New Wave” (1981) with the panic and excitement of those dangerous, seemingly lawless days. “The Real Estate Show” happened because the artists took over a city-owned building on Delancey Street: they didn’t ask permission; they just stuffed the derelict space with sculptures, paintings, and so on by members of what would become ABC No Rio, a collaborative made up of artists and activists who worked on the Lower East Side, and Collaborative Projects Inc. (or Colab), which promoted artists working in different disciplines to experiment together.

Ahearn was also instrumental in making “The Times Square Show” happen. Set up in a former massage parlor and bus depot on West 41st Street and Seventh Avenue in the heart of one of the sleazier areas in a city filled with sleazy areas, the show stands out in my mind less because of the art I discovered in that jumble of xeroxed pictures, thrift stores fashioned into sculpture, dirt, and so on, than the urgency that permeated the enterprise.

Kids were making things as though their lives depended on it and what did that even mean in a city whose citizens, it was reported, President Gerald Ford had told to drop dead? I didn’t think of anything I saw as being part of “identity politics” but, rather, as the work of the younger, funkier siblings to the “Fluxus” movement of the 1960s—inspired by John Cage, among others—which combined visual arts and music and graphic design. Like Fluxus art, a number of the objects in “The Times Square Show” would disappear in the years after they were first shown there, and they disappeared because they could not be commodified—that helped to shut connoisseurship out. “What we can finally see from the ’70’s,” wrote the late art critic Rene Ricard in a 1981 piece about Jean-Michel Basquiat, “was at least one academy without program.” The times, he said, were defined by the “institutionalization of the idiosyncratic.”

I didn’t think of any of those three New York shows as “multiculturalism” or a concerted effort to diversify the art scene. It was an unforced dialogue with the real world—the world I lived in, and the one that Basquiat, making pictures like 1983’s Untitled (History of the Black People), lived in: one that acknowledged one’s legacy as a former citizen of the old continent—Africa—while being cognizant of how that legacy got fractured and dissembled under what Toni Morrison called the “white gaze,” that which wants to remake the world in its own image—or for its own sense of security. What thrilled at “The Times Square Show,” and “New York/New Wave,” was that you could not differentiate between the work done by women, blacks, Hispanics, Jews, or whatever—no work was subjected to being anthropologized. I did not feel “black” or “gay” standing at PS 1 or in any number of buildings that had been taken over. Rather, I felt like a citizen of an intense world, one where the so-called marginalized were in the majority, and everyone always feels better being in the majority.

But that may not be the best thing for art. The jolt I felt when I first saw Doig’s paintings in this magazine in 2008* had to do with how much I hadn’t seen in the years previously: I had been too mired in what I had missed in my first art-going forays, and the subsequent confusion I had felt about the artist’s role in contemporary society. Indeed, a large portion of my confusion had to do with those uninspired artists of color who, taking the fashionable route, made work that addressed the subject of their “otherness,” and for a largely white audience, as if their difference was the whole story. (The actor Morgan Freeman once said: “I don’t play black; I am black.”)

Looking at some of that agitprop I felt my eyes were losing out. I also had to work hard to get past the Museum of Modern Art’s 1984 “Primitivism” show, about which Janet Malcolm wrote so brilliantly in her 1986 profile of Artforum’s then editor, Ingrid Sischy. In that piece, Malcolm charts a time when the art market, intellectually and aesthetically, was moving away from the chilly precocity and hysteria of 1960s Pop and 1970s hermeticism to something else. The editor told the reporter of her experiences at the “Primitivism” show—a defining moment:

As I went along, I began to feel yet again the Other was being used to service us. Yet again. Practically a thesis had been written on the label below a Brancusi work, but it was enough to say of the primitive culture beside it, “From North Africa.”… A supposed honor was being bestowed on primitive work—the honor of saying, “Hey! It’s as good as art!” But now we know that a different set of questions needs to be asked about how we assimilate another culture.

The faulty thinking behind the “Primitivism” show and the ensuing controversy is not anything the art world wants to face again and so, in an effort to not affirm “our values”—to not, as it were, put all the research into the Brancusi—a little leveling or equalizing must go on. For some prophets of displeasure, artists like Doig, despite making events like the StudioFilmClub happen, are intellectually marginalized, or viewed with distrust because they are seen as well-connected white male artists. Doig’s remarkable success in the market has only fed his detractors, but looking closely at his many paintings and prints and posters, one can’t fail to see, after a while, that the black forms in his work are unhindered by ideology, just as his other characters’ whiteness was, too: their figures were, again, just correct for the paintings.

This beautiful equilibrium is perfectly realized in this year’s show of Doig’s work in Venice. Composed of fourteen images of varying sizes—some smaller than Doig has ever exhibited, aside from the Ofili collaborations—the pieces are divided between five rooms.

Organized by the artist, the show tells a story, and it’s this: Doig is no longer describing other people or otherness and how it affects him; here he’s talking more directly about himself. The moist air and crumbling walls only add to the show’s vulnerable and romantic qualities, which are enhanced by several pieces that show the artist not alone, but in the presence of a young woman, sometimes shrouded as in Spearfishing (2013) and Spearfisher (2015), who sits with Doig in that 100 Years-type boat. But by the end of the show, the same young woman emerges as an arresting figure on her own in Untitled (portrait) (2015), outside of the artist’s shared narrative. (The artist cannot “possess” her, nor does he want to; as in his previous work crowded with all those other people, the young woman in the new work exists as herself, and as someone who changes, yet again, what Doig is looking at, and why.)

I say “vulnerable” because in at least four of the pictures, Doig paints himself. Horse and Rider (2014) shows the artist in a pose that recalls John Berger’s criticism of the world De Witte made. But Doig’s “possessions” and attitude are different from old Admiral De Ruyter’s. Sitting astride a black horse, the artist’s countenance—pale-skinned and closemouthed—is framed by a Napoleonic hat (the same costuming one finds in his Ofili paintings), costuming that one finds looks out at us in the exhibition against a background that is half nature (stars and water) and half “art” (the Mondrian squares of his Ping Pong (2006–2008)). Each is his, but how can you possess nature and inspiration?

In the self-portrait Night Studio (STUDIOFILM & Racquet Club) (2015), the artist is seen in a blue T-shirt and trousers; he stands on a bright red floor and is leaning back, like one of the American painter Robert Longo’s Men in the Cities figures. Here his skin is no longer white, as in Horse and Rider; instead Doig has rendered himself in various shades of red and deep pink and brown—colors that complement one another as they do in life. Unlike one of Longo’s figures, though, the artist in Night Studio has a different source: Doig’s Stag (2002–2005), named after a popular beer in Trinidad. In Stag, we see a lone man standing amid the foliage—the vertical version of the man in 100 Years—his head surrounded by light, not unlike traditional paintings of Jesus. This mysterious figure is emerging out of the density, while in Night Studio, the painter, sans metaphor, rises up, dancing, in front of the hanging and climbing foliage—green and yellow and tangled plant life that suggests Trinidad’s natural world, filled with blood and history—a world Doig has made and that has made him.

-

*

See Sanford Schwartz, “Enchanted & Ominous,” The New York Review, July 17, 2008. ↩