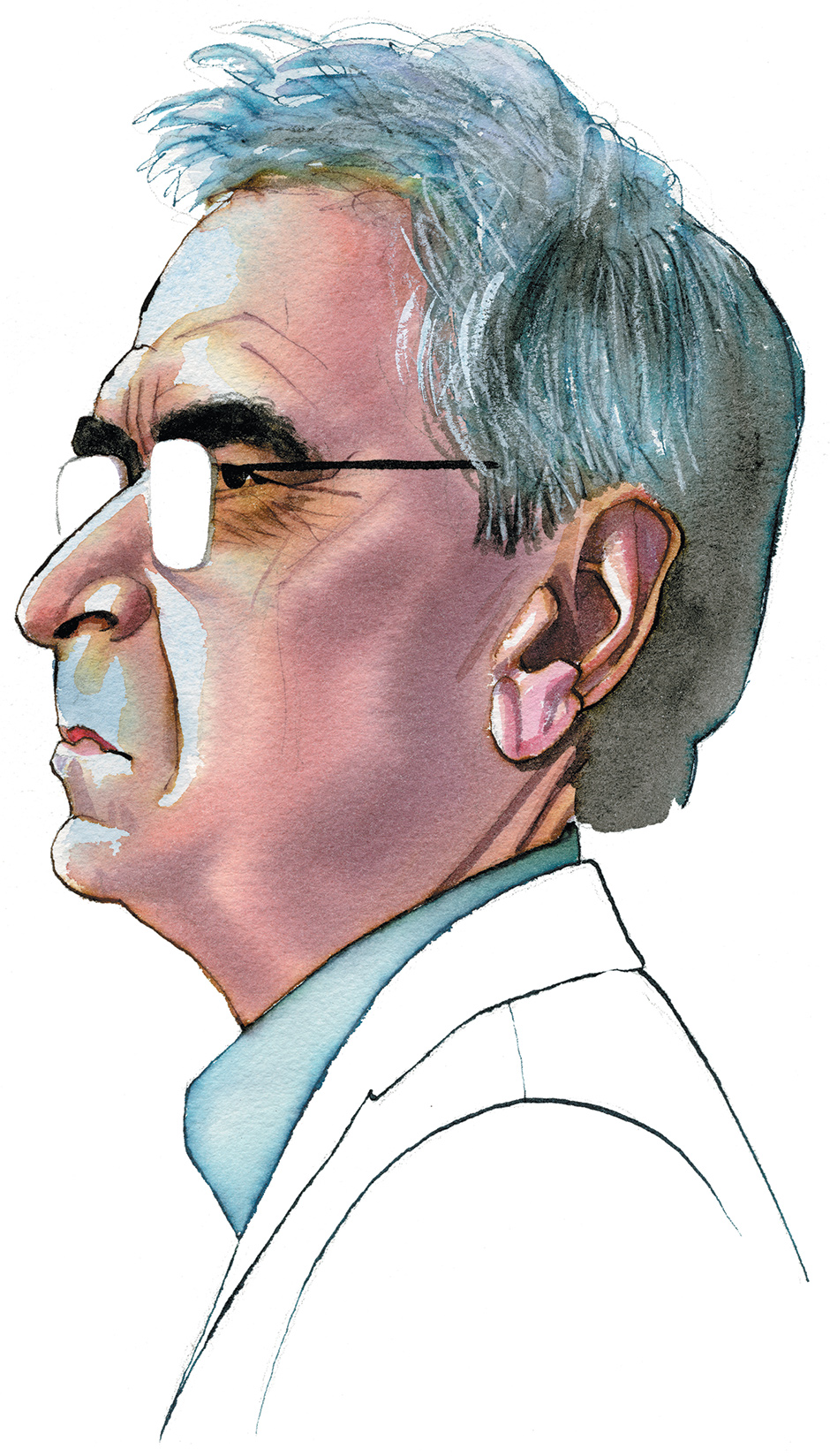

“I don’t believe art has redemptive qualities.” The demur comes from Philippe de Montebello, who, having served as director of the Metropolitan Museum of Art for an unparalleled thirty-one years before his retirement in 2008, must by any reckoning be one of the most eminent figures in the art world. Before asking why he of all people should make such a statement in Rendez-vous with Art, a book about aesthetic pleasures, one might try to define the proposition he is declining.

What would it mean for art to have redemptive qualities? It might mean that art has a necessary and structural part in human affairs, comparable to Christ’s in a religious scheme of salvation. It would at least imply that art compensates for some sort of lack in our lives or in the world and that it does so in a satisfying manner. This is a tenet that a great many people in the art scene—practitioners, collectors, dealers, critics, educators, curators—adhere to. It would seem a fortifying belief, whether you are conducting art therapy sessions or trying to persuade politicians to allocate money to cultural projects.

But de Montebello has no need for it. Rendez-vous with Art, a record compiled by the critic Martin Gayford of discussions he has held with de Montebello in the course of their visiting various museums, acquaints us with the style of the retired director’s agnosticism and with the complex of feelings in which it is lodged. One way to interpret de Montebello’s position might be that we do not usually regard the ground beneath our feet as “redemptive.” He has been a creature of the art world from the moment of his birth in Paris seventy-nine years ago. His aunt was the great patron of the Surrealists, the Vicomtesse de Noailles; his maternal grandfather Francis Croisset was a playwright; while his father, from a line of soldiers and politicians ennobled by Napoleon, had turned to painting and to art criticism.

Philippe, having crossed the Atlantic with his parents during his high school years, progressed to study art history at Harvard and then at New York’s Institute of Fine Arts. From this he launched into a surefooted career in museums that eventually led to his appointment as the Met’s director at the age of forty-one. As the spokesman for the largest art collection in the United States, de Montebello has appeared not so much an advocate as an embodiment of high cultural values: the steady-tempered, genially diplomatic, patrician discharger of a responsibility that is of its nature conservative.

How far does this impression tally with his own experience? Freer to speak now that he is retired, de Montebello qualifies it merely by emphasizing that a museum directorship is not a position of unassailable eminence. The curator may have the scorn of the academic to contend with: “Oh, what a waste!” was the comment he heard from a scholar at the Institute of Fine Arts when first he joined the Met; he had opted, in the speaker’s eyes, to stoop from theoretical discriminations to the compromises entailed in deciding on acquisitions and handling public response. Moreover, the overseer of the museum’s many departments may need to become a lowly apprentice to their respective keepers: de Montebello tells of the “long learning process” at the hands of one of them, which delivered him from regarding “galleries of Greek vases with a sense of dread.”

Altogether, his recollections of his directorship bear out the time-honored principle that the good master is the good servant—or student—and his lapidary sentences rarely stray from respectfulness. An aside about the potential “vulgarity” of Sèvres porcelain—“There, I’ve just lost a few friends over that one!”—is about as near as he gets to departmental jousting.

At the same time, de Montebello has given service to a form of institution caught up in “many inherent paradoxes.” For instance, he notes that whereas museums make possible the “magical, individual and silent colloquy between the work of art and the viewer,” the more that viewers in their numbers seek out that communion, the harder it becomes for any of them—peering over one another’s shoulders—to attain it. On another level, the more that museums broaden our awareness of world culture, the more they expose contradictions in international relations:

The colonial rapine of Cambodia yielded this great collection [the curator and critic are at this point looking at the Khmer carvings in Paris’s Musée Guimet]; but paradoxically, it is as a result of this that the civilization was first seriously studied. In our day, when we relish wallowing in retrospective guilt, we need to remember that there was a repayment in scholarship and knowledge.

De Montebello, as his tone here shows, settles willingly for that historical outcome. Yes, he affirms, “the art museum is a completely Western construct” (elsewhere, he has indeed characterized it as “a fiction”*), “exported,” long after its formation during the Enlightenment, to Asian and African nations. Yes, there are inevitable tensions involved in uprooting any artifact made for a specific purpose and place and setting it before alien eyes, and yet “after an extended period of time the work’s life in another context becomes a legitimate and often meaningful layer of its history.”

Advertisement

Doesn’t such a finders-keepers legitimation all too easily shade into “If two wrongs don’t make a right, try three”? De Montebello, however, would see it as a necessary coming to terms with circumstance. Times are bound to change, and as a result, “a large number of objects in the museum have been—ugly word—desacralized.” Martin Gayford lays before him the standard objection: “Some would say that putting a religious work in a museum removes its most crucial meaning.” “Well,” comes the reply, “the meanings are in danger of disappearing anyway.”

Objects remain while thoughts about them evaporate, and though Gayford also floats the familiar analogy between a museum and a temple, that can at best only partly be true. But how will de Montebello’s feelings on this issue square with the feelings he expresses about individual works of art? The discussion wanders from museum to museum, and the two art-lovers arrive at Rotterdam’s Boijmans van Beuningen, where they stand before a little devotional panel by Geertgen tot Sint Jans. It leads de Montebello to consider

one of the characteristics of great art, which is that it must “work,” that formal artistic conception and purpose must so perfectly translate, as in this case, the votive purpose, that icon and art are inextricably fused.

We hit here another paradox. The crux of that statement is the quotes around the word “work”—because, in truth, this panel in a museum does not now work. It no longer impels viewers to pray to the Madonna and Child; it no longer holds out a promise of redemption. And yet, de Montebello is saying, its artistic quality lies in the integrity of its intention. The sign may send us nowhere, but it most distinctly points.

This, his commentaries suggest, is the fulcrum of the de Montebello aesthetic, the state of happy suspension toward which he likes to gravitate. It is no surprise that de Montebello’s career has equipped him to deliver poised and informative appreciations of almost everything the two men encounter during their tours of the great museums of Florence, Paris, Madrid, London, and the Netherlands. But he is never more engaged and passionate than when brought before pieces so ancient that the realities to which they once pointed have become irrecoverable. Why, some 2,400 years ago, did an unknown artist create the snarling bronze lion, sporting a goat’s head at its withers and a snake’s on its tail, that is now on view in Florence’s Archaeological Museum under the name of the Chimera of Arezzo? As with so much in Etruscan culture, answers are hard to come by. But that artist is a hero to de Montebello, who, having by his own account “waxed dithyrambic” about the sculpture’s detailing, concludes that “he knew exactly what he wanted to convey and succeeded brilliantly in doing so.”

The Chimera is at bay, perhaps facing a now vanished assailant. Still more so the lions mown down with arrows by the king of Assyria, in the bas-reliefs from the seventh century BC on display in the British Museum. For de Montebello—and this is where the heterodox provocateur in him starts to find a voice, knowing that the Parthenon marbles lie just around the corner—these reliefs are “the pinnacle of art.” For him, no portrayal of human pathos in the Western tradition that followed can match the represented sufferings of Ashurbanipal’s wounded noble beasts. The ritual immolation of the Near East’s long-extinct fauna is “emotionally wrenching” to a degree he finds positively delicious. It would seem that the very disconnection from modern circumstance feeds his fascination. By contrast he finds a Bruegel painted a mere 453 years ago, The Triumph of Death, nearly impossible to look at in its all too sharp foretaste of twentieth-century horrors.

Another de Montebello touchstone—the item from his own museum before which the set of discussions actually begins—is a fragment of a shattered head from ancient Egypt, a shard of burnished jasper featureless but for a pair of lips. The lips are mesmerizingly sexy. It was in displaced desire, de Montebello a few pages later confesses, that his personal engagement with art began: by falling in love, in his early teens, with a black-and-white photograph of the thirteenth-century limestone head of Marchioness Uta in Naumburg Cathedral, with “her puffed eyelids, as though after a night of lovemaking…. I still think she’s one of the most beautiful women in the world.”

Advertisement

With this disarming avowal, de Montebello clears the way for the broader revisionism he aims at. He may belong to “the generation that grew up with formalist art history” and he may accept that when Khmer carvings enter the museum, “their formal, aesthetic character trumps their religious and cultural meaning,” yet he has grown skeptical about the notion of “a pure aesthetic response.” “Is there ever such a thing?” he wonders. Shouldn’t we give voice to the complexity of motives involved in all our viewing? And so de Montebello has embarked on this peripatetic dialogue meant to explore, in Gayford’s words, “the actual experience of looking at art.”

Gayford seems a fitting ally in such an enterprise, an English art critic whose journalism over the past thirty years has been warmhearted, unstuffy, and dependably well informed. Previous books of Gayford’s have viewed art through the lenses of one-to-one relationships: that between Van Gogh and Gauguin, for instance, or that between Lucian Freud and the writer himself, posing for a portrait. Gayford and his current interlocutor have plenty to bond over. They both relish a sure and painterly handling of oils, with Rubens and Goya uniting them in rhapsodies. Mild divergences do inevitably appear. Gayford, an English Romantic heat-seeker, plumps for Titian as the greatest of painters, whereas his companion prefers the cool of Velázquez.

“I was beginning to get a feeling for Philippe’s taste,” Gayford observes in one of his paragraphs that link their conversations. “The pictures he is drawn to have a quality of silence and restraint.” A church interior by Pieter Jansz. Saenredam is an instance of this: de Montebello admiringly compares it to Jasper Johns’s laconic White Flag—one of his very rare references to art after Manet. A patrician distaste keeps de Montebello away from anyone who might be shouty, such as Turner, while Rembrandt with his emphatic impastos he considers too attention-seeking, “too Rembrandtesque.”

Gayford suppresses any outrage he may feel at this. “We won’t argue, because there is famously no arguing about such matters of taste.” The instant truce is meant genially and also deferentially: these may be “discussions,” but there is a clear order of seniority. Good humor is maintained, allowing Gayford to pipe up with opinions vouchsafed him by famous interviewees such as David Hockney or Luc Tuymans, and allowing de Montebello to relay some handsome set-piece anecdotes: notably, about being caught by the 1966 flood of the Arno while studying in Florence and climbing the hills the next day to the villa of the renowned aesthete Harold Acton, to announce in muddy boots that the golden Ghiberti panels on the Baptistery doors, the so-called Gates of Paradise, were now scattered in the waters.

Gayford, transcribing the impeccably elegant commentaries of de Montebello and providing some covering narrative, falls in with the retired director’s inclination: in a belated riposte to formalism and classicism, this text will stress the circumstantiality of their encounters with art. That suits his comfortable English empiricism. He remembers that “Lucian Freud once said to me that ‘in the end nothing goes with anything, it’s your own taste that puts things together.’” He reflects that Philippe’s responses to a work they are both inspecting will be conditioned by the presence of his own company: “Everything is like that.”

He readily records that aesthetic alertness was bound to flag when “Philippe’s back was hurting” and “I had a Eurostar train to catch”: good lunches, museum cafés, and receptions with prosecco feature prominently in the story also. By many such steppings down, and by dutiful homages to works and themes (Las Meninas, the ideas of Walter Benjamin) on which neither man has anything new to say, an idiosyncratic dialogue between two articulate and learned observers descends into stretches of banality.

Why does Gayford have to be always so awfully polite? Why won’t he push de Montebello on Rembrandt, or on his indifference to modernism, or on an equivocal remark that has had me hunting for a context? The two men are considering a lovely Annunciation by Fra Angelico in the Prado, before which de Montebello’s customary resourcefulness seems rather to fail: “There is something so angelic—shall we dare to say?—about Gabriel.” It is a few lines afterward that he falls back to remarking that “I don’t believe art has redemptive qualities, but looking at this makes me feel better.” Well, ask him, then, Martin: So does this business of looking at artifacts serve some purpose in the world, or doesn’t it? Until we get to hear de Montebello’s answer, all I can suggest is a paraphrase of the problem.

There is the thought that everything we do may be loaded with meaning in some large and permanent perspective, and there is the opposing thought that everything we do is weightless and meaning-free, since all things will pass. Although Milan Kundera entitled his fictional meditation on this theme The Unbearable Lightness of Being, he suggested that each thought was equally hard to sustain. The experience that Kundera’s narrative illumines in the light of the alternatives is sexual love. I think the book by de Montebello and Gayford could be read as an attempt to position the love of art in a comparable light. Ars longa, vita brevis, the old saw goes, and the colonnaded portals of a museum such as the Met seem to concur, suggesting that human visual inventiveness has reached its final destination and that you are entering the zone of immutability.

The ex-director and his friend try to tug the opposite way, insinuating that the museum is at root a fiction and that experiences of art can never be more than encounters, a scattering of rendezvous, in a world where all is fleeting contingency. Each artifact is a little endpoint: it is not to be argued that they lead anywhere, let alone redeem anything on the street outside. And yet the works themselves seem to drag so frantically back in the other direction, toward plenitude of meaning. You are left with the echoes of de Montebello’s exclamation, as he gets caught up in the force field of a Velázquez or a Rubens: “There, this is life!”

-

*

“In Conversation: Philippe de Montebello with David Carrier and Joachim Pissarro,” The Brooklyn Rail, May 6, 2014. This article explores de Montebello’s thoughts about museums more provocatively than the present book. ↩