I think that I should begin by evoking René Magritte’s famous painting of 1929, The Treachery of Images, with its simple, literal depiction of a pipe and the provocative caption beneath—Ceci n’est pas une pipe. “This is not a pipe.” (How strangely people seem to have reacted to this self-evident statement! Though no one in actual life would confuse a pipe with the drawing of a pipe.)

This is not a traditional lecture so much as the quest for a lecture in the singular—a quest constructed around a sequence of questions: Why do we write? What is the motive for metaphor? “Where do you get your ideas?” Do we choose our subjects, or do our subjects choose us? Do we choose our “voices”? Is inspiration a singular phenomenon, or does it take taxonomical forms? Indeed, is the uninspired life worth living?

Why did I write? What sin to me unknown

Dipt me in Ink, my Parents’, or my own?

Alexander Pope’s great “Epistle to Dr. Arbuthnot” (1735) asks this question both playfully and seriously. Why did the child Pope take to verse at so young an age, telling us, as many a poet might tell us, with the kind of modesty that enormous self-confidence can generate, “I lisp’d in Numbers, for the Numbers came,” by which the poet means an intuitive, instinctive, “inborn” sense of scansion and rhyme for which some individuals have the equivalent of “perfect pitch” in music: you are born with it, or you are not.

For sheer virtuosity in verse, Pope is one of the great masters of the language; his brilliantly orchestrated couplets lend themselves ideally to the expression of “wit” (usually caustic, in the service of the poet’s satiric mission). The predilection to “lisp in numbers” suggests a kind of entrapment, though Pope doesn’t suggest this; the perfectly executed couplet with its locked-together rhymes is a tic-like mannerism not unlike punning, to which some individuals succumb involuntarily (“pathological punning” is a symptom of frontal lobe syndrome, a neurological deficit caused by injury or illness) even as others react with revulsion and alarm.

Pope’s predilection for “lisping in numbers” seems to us closely bound up with his era, and his talent a talent of the era, which revered the tight-knit grimace of satire and the very sort of expository and didactic poetry from which, half a century later, Wordsworth and Coleridge would seek to free the poet. Pope never suggests, however, that the content of poetry is in any way inherited, like the genetic propensity for scansion and rhyme; he would not have concurred (who, among the poets, and among most of us, would so concur?) with Plato’s churlish view of poetry as inspired not from within the individual poet’s imagination but from an essentially supranatural, daimonic source.

To Plato, poetry had to be under the authority of the state, in the service of the (mythical, generic) Good; that it might be “imitative” of any specific object was to its discredit. “No ideas but in things,” the rallying cry of William Carlos Williams in the twentieth century, would have been anathema to the essentialist Plato, like emotion itself, or worse yet, “passion.” Thus, all “imitative” poetry, especially the “tragic poetry” of Homer, should be banished from the Republic, as it is “deceptive,” “magical,” and “insincere.” With the plodding quasi logic of a right-wing politician, Plato’s Socrates dares to say, in the Ion:

In fact, all the good poets who make epic poems [like Homer] use no art at all, but they are inspired and possessed when they utter all these beautiful poems, and so are the good lyric poets; these are not in their right mind [italics mine] when they make their beautiful songs…. As soon as they mount on their harmony and rhythm, they become frantic and possessed…. For the poet is an airy thing, a winged and a holy thing; he cannot make poetry until he becomes inspired and goes out of his senses and no mind is left in him…. Not by art, then, they make their poetry…but by divine dispensation; therefore, the only poetry that each one can make is what the Muse has pushed him to make…. These beautiful poems are not human, not made by man, but divine and made by God: and the poets are nothing but the gods’ interpreters….

The poets whom Plato disdained (and feared) were analogous to our rock stars, before large and enthusiastic audiences; we can assume that it wasn’t the fact that these poets were popular, as Homer was popular, to which Plato objected, but the fact that his particular heavily theologized philosophy didn’t form the content of their utterances. The poet’s right mind should be under the authority of the state—indeed each citizen’s right mind should be a part of the hive mind of the Republic. That the freethinking, rebellious, and unpredictable poet-type must be banished from the claustrophobic Republic is self-evident. (In one of the great ironies of history, it was to be Plato’s Socrates who was banished from the state.)

Advertisement

The worksheets of poets as diverse as Dylan Thomas, William Butler Yeats, Elizabeth Bishop, and Philip Larkin suggest how deliberate is the poet’s art, and how far from being inspired by a (mere) daimon; though it is often the poet’s wish to appear spontaneous, unstudied—see Yeats’s “Adam’s Curse”:

We sat together at one summer’s end,

That beautiful mild woman, your close friend,

And you and I, and talked of poetry.

I said, “A line will take us hours maybe;

Yet if it does not seem a moment’s thought,

Our stitching and unstitching has been naught.

Better go down upon your marrow-bones

And scrub a kitchen pavement, or break stones

Like an old pauper, in all kinds of weather;

For to articulate sweet sounds together

Is to work harder than all these, and yet

Be thought an idler by the noisy set

Of bankers, schoolmasters, and clergymen

The martyrs call the world.”And thereupon

That beautiful mild woman for whose sake

There’s many a one shall find out all heartache

On finding that her voice is sweet and low

Replied, “To be born woman is to know—

Although they do not talk of it at school—

That we must labour to be beautiful.”

I said, “It’s certain there is no fine thing

Since Adam’s fall but needs much labouring….”

Very different from the Beats’ notorious admonition: “First thought, best thought.”

To appear spontaneous and unresolved, even as one is highly calculated and conscious—this is the ideal. As Virginia Woolf remarked in her diary in 1925, in an aside that seems almost to prefigure her suicide in 1941 at the age of fifty-nine:

I do not any longer feel inclined to doff the cap to death. I like to go out of the room talking, with an unfinished casual sentence on my lips…. No leavetakings, no submission—but someone stepping out into the darkness.

“Inspiration” is an elusive term. We all want to be “inspired” if the consequence is something original and worthwhile; we would even consent to be “haunted”—“obsessed”—if the consequence were significant. For all writers dread what Emily Dickinson calls “Zero at the Bone”—the dead zone from which inspiration has fled.

What does it mean to be captivated by an image, a phrase, a mood, an emotion?

A picture held us captive. And we could not get outside it, for it lay in our language and language seemed to repeat it to us inexorably.

—Ludwig Wittgenstein, Philosophical Investigations

Most serious and productive artists are “haunted” by their material—this is the galvanizing force of their creativity, their motivation. It is not and cannot be a fully conscious or volitional “haunting”—it is something that seems to happen to us, as if from without, no matter what craft is brought to bear upon it, what myriad worksheets and note cards. Here is Emily Dickinson’s cri de coeur: “To Whom the Mornings stand for Nights,/What must the Midnights—be!”

Most of the Dickinson poems we revere and that have lodged deeply into us are beautifully articulated, delicately calibrated cries from the heart—formulations of unspeakable things, at the point at which “poetic inspiration” has become something terror-filled:

The first Day’s Night had come—

And grateful that a thing

So terrible—had been endured—

I told my Soul to sing—She said her Strings were snapt—

Her bow—to Atoms blown—

And so to mend her—gave me work

Until another Morn—And then—a Day as huge

As Yesterdays in pairs,

Unrolled its horror in my face—

Until it blocked my eyes—My Brain—begun to laugh—

I mumbled—like a fool—

And tho’ ’tis Years ago—that Day—

My Brain keeps giggling—still.And Something’s odd—within—

That person that I was—

And this One—do not feel the same—

Could it be Madness—this?

This is the very voice of inwardness, compulsiveness, the “Soul at the White Heat” of which Dickinson speaks in the remarkable poem that seems almost to deconstruct the Platonic charge of “god”-inspiration:

Dare you see a Soul at the White Heat?

Then crouch within the door—

Red—is the Fire’s common tint—

But when the vivid Ore

Has vanquished Flame’s conditions,

It quivers from the Forge

Without a color, but the light

Of unanointed Blaze….

There is another Dickinson whose inspiration is clearly more benign, drawn from the small pleasures and vexations of daily life, a shared and domestic life in her father’s house in Amherst, Massachusetts:

Advertisement

A Rat surrendered here

A brief career of Cheer

And Fraud and Fear.Of Ignominy’s due

Let all addicted to

Beware.The most obliging Trap

Its tendency to snap

Cannot resist—Temptation is the Friend

Repugnantly resigned

At last.

This is surely the most brilliantly crafted poem ever written on the subject of a rat found dead in a rat trap—in the cellar perhaps. And behind the house:

A narrow Fellow in the Grass

Occasionally rides—

You may have met Him—did you not

His notice sudden is—The Grass divides as with a Comb—

A spotted shaft is seen—

And then it closes at your feet

And opens further on—…Several of Nature’s People

I know, and they know me—

I feel for them a transport

Of cordiality—But never met this Fellow

Attended, or alone

Without a tighter breathing

And Zero at the Bone—

In the tersely titled “Pig” by the contemporary poet Henri Cole, the (trapped, doomed) animal that is the poem’s subject fuses with the poet-observer in the way of a vivid and revelatory dream:

Poor patient pig—trying to keep his balance,

that’s all, upright on a flatbed ahead of me,

somewhere between Pennsylvania and Ohio,

enjoying the wind, maybe, against the tufts of hair

on the tops of his ears, like a Stoic at the foot

of the gallows, or, with my eyes heavy and glazed

from caffeine and driving, like a soul disembarking,

its flesh probably bacon now tipping into split

pea soup, or, more painful to me, like a man

in his middle years struggling to remain

vital and honest while we’re all just floating

around accidental-like on a breeze.

What funny thoughts slide into the head,

alone on the interstate with no place to be.—Touch (2011)

(Parenthetically, I should mention that I read this poem when I taught several writing workshops at San Quentin in 2011, on my first meeting with the inmate-writers; in fact, I had to read it twice. The students were fascinated and moved by this poem, in which they saw themselves all too clearly.)

In these striking poems by Dickinson and Cole the poet appropriates a “natural” sighting of one of “Nature’s People.” These are not “found” poems except in their suggestion that the poet’s sighting has an element of accident, one within the range of all of us—the rat in the trap, the snake in the grass, the pig on the flatbed being borne along a highway to slaughter. The poet is the seer; the poem is the act of appropriation. We might wonder: Would the poem have been written without the sighting? Would another poem have been written in its place, at just that hour? Is it likely that the poet’s vision is inchoate inside the imagination and is tapped by a sighting in the world, which triggers an emotional rapport out of which the poem is crafted? If we consider in such cases what the poet has made out of the sighted object that is, but is not, contained within the subject, we catch a glimpse of the imagination akin to a flammable substance, into which a lighted match is dropped.

Dickinson’s poems, and her letters as well, which seem so airy and fluent, give the impression of being dashed off; in fact, Dickinson composed very carefully, sometimes keeping her characteristically enigmatic lines and images for years before using them in a poem or in a letter. It is a fact that the human brain processes only a small selection of what the eye “sees”—so too, the poet is one who “sees” the significant image, to be put to powerful use in a structure of words, while discarding all else.

This is going to be fairly short: to have father’s character done complete in it; & mother’s; & St. Ives; & childhood; & all the usual things I try to put in—life, death, &c. But the centre is father’s character, sitting in a boat, reciting We perished, each alone, while he crushes a dying mackerel.

Here is Virginia Woolf musing in her diary for May 14, 1925, on To the Lighthouse, about which she will say, months later, that she is being “blown like an old flag by my novel…. I live entirely in it, & come to the surface rather obscurely & am often unable to think….”

Woolf suggests the power of a different sort of inspiration, the sheerly autobiographical—the work created out of intimacy with one’s own life and experience. Yet here also the appropriative strategy is highly selective, as in memoir; the writer must dismiss all but a small fraction of the overwhelming bounty of available material. What is required, beyond memory, is a perspective on one’s own past that is both a child’s and an adult’s, constituting an entirely new perspective. So the writer of autobiographical fiction is a time traveler in his or her life and the writing is often, as Woolf noted, “fertile” and “fluent”:

I am now writing as fast & freely as I have written in the whole of my life; more so—20 times more so—than any novel yet. I think this is the proof that I was on the right path; & that what fruit hangs in my soul is to be reached there…. The truth is, one can’t write directly about the soul. Looked at, it vanishes: but look [elsewhere] & the soul slips in.

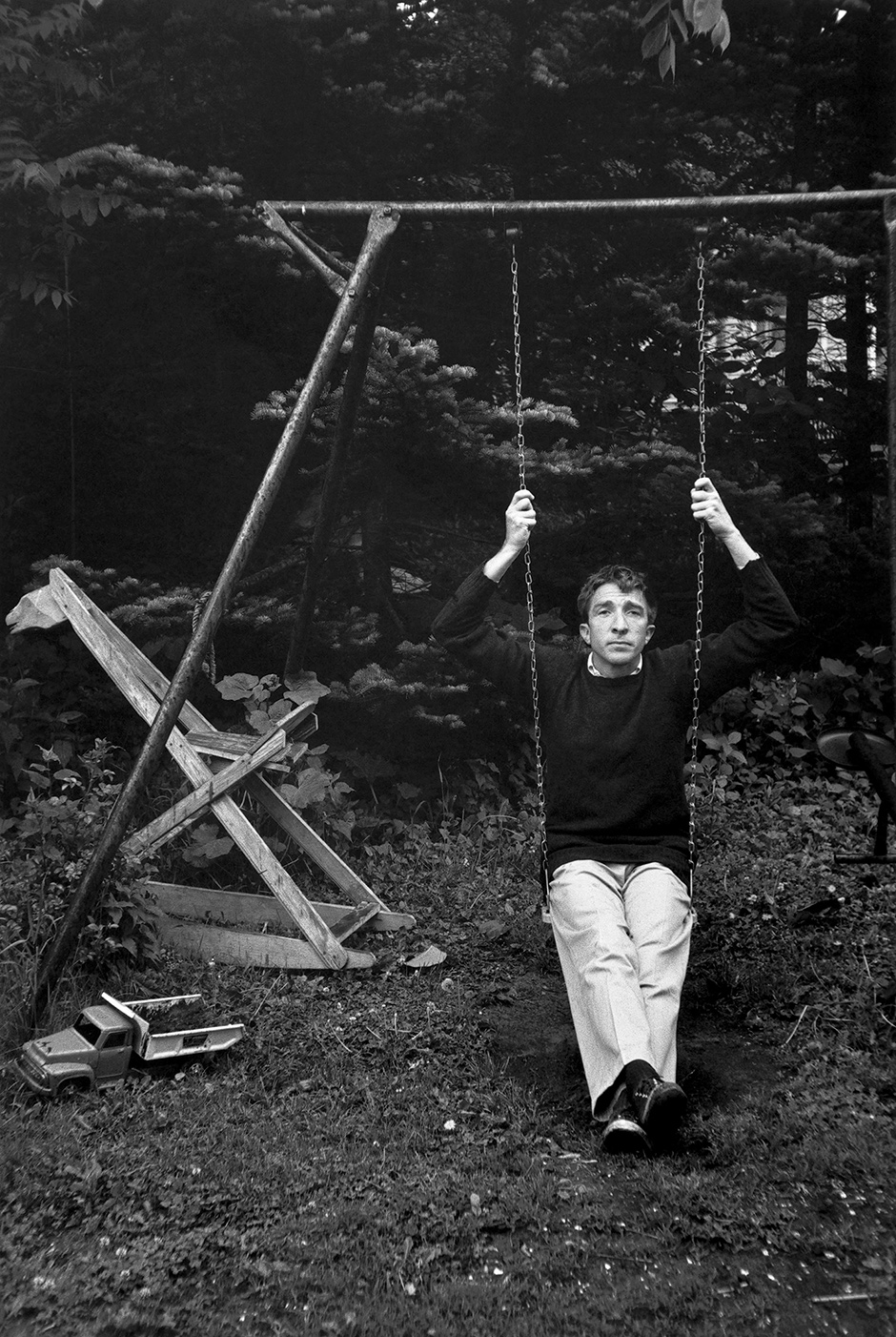

John Updike’s first novel, The Poorhouse Fair (1959), published when the author was twenty-six, is a purposefully modest work composed in a minor key; unlike Norman Mailer’s first novel, The Naked and the Dead (1948), also published when the author was twenty-six. Where Mailer trod onto the literary scene like an invading army, with an ambitious military plan, Updike seems almost to have wished to enter by a rear door, claiming a very small turf in rural eastern Pennsylvania and concentrating upon the near-at-hand with the meticulous eye of a poet.

The Poorhouse Fair is in its way a bold avoidance of the quasi-autobiographical novel so common to young writers: the bildungsroman of which the author’s coming-of-age is the primary subject. Perversely, given the age of the author, The Poorhouse Fair is about the elderly, set in a future only twenty years distant and lacking the dramatic features of the typical future, dystopian work; its concerns are intrapersonal and theological. By 1959 Updike had already published many of the short stories that would be gathered into Olinger Stories, which constituted in effect a bildungsroman, freeing him to imagine an entirely other, original debut work.

The Poorhouse Fair, as Updike was to explain in an introduction to the 1977 edition of the novel, was suggested by a visit, in 1957, to his hometown, Shillington, which included a visit to the ruins of a poorhouse near his home. The young author then decided to write a novel in celebration of the fairs held at the poorhouse during his childhood, with the intention of paying tribute to his recently deceased maternal grandfather, John Hoyer, given the name “John Hook” in the novel. In this way The Poorhouse Fair both is not, and is, an autobiographical work, as its theological concerns, described elsewhere in Updike’s work, were those of the young writer at the time.

Appropriately, Updike wrote another novel set in the future near the end of his life, Toward the End of Time (1997), in which the elderly protagonist and his wife appear to be thinly, even ironically disguised portraits, or caricatures, of Updike and his wife in a vaguely postapocalyptic world bearing a close resemblance to the Updikes’ suburban milieu in Beverly Farms, Massachusetts. Is it coincidental that Updike’s first novel and his near-to-last so mirror each other? Both have theological concerns, and both are executed with the beautifully wrought, precise prose for which Updike is acclaimed; but no one could mistake Toward the End of Time, with its bitter self-chiding humor and tragically diminished perspectives, for a work of fiction by a reverent and hopeful young writer.

Love at first sight. In literary inspiration, as in life, such a blow to one’s self-sufficiency and self-composure can have profound, ambiguous consequences. For here is another sort of inspiration that we might call the encounter with the Other.

He had been highly successful with his first two novels, quickly written in his early twenties following his seafaring adventures in the South Seas—Typee: A Peep at Polynesian Life (1846) and Omoo: A Narrative of Adventures in the South Seas (1847). Now, he was working energetically on a third seafaring novel narrated in a similar storytelling voice, this time set on a New England whaling ship called the Pequod. (As a young man, he’d sailed with a New Bedford whaler into the South Pacific where, after eighteen months, he’d jumped ship in a South Seas port; going to sea was, for Herman Melville, “the beginning of my life.” And now he was working industriously on this new novel when a book of short stories came into his house—Nathaniel Hawthorne’s Mosses from an Old Manse, which had been published a few years earlier, in 1846.

Melville, at thirty-one younger than Hawthorne by fifteen years, read this collection of anecdotal and allegorical tales with mounting astonishment. There was the affable, sunny Hawthorne, as he seems to have been generally known to contemporary readers, and there was the other, darker and deeper Hawthorne: “It is that blackness in Hawthorne…that so fixes and fascinates me.” Soon, Melville was moved to write the first thoughtful appreciation of Hawthorne, “Hawthorne and His Mosses” (1850), in which Melville speculates that “this great power of blackness in him derives its force from its appeal to that Calvinistic sense of Innate Depravity and Original Sin, from whose visitations…no deeply thinking mind is always and wholly free.”

Hawthorne’s influence upon Melville was immediate and profound. What would have been another seafaring adventure tale, very likely another best seller, was transformed by the enchanted Melville into the intricately plotted, highly symbolic, and poetic Moby-Dick, the greatest of nineteenth-century American novels, as it is one of the strangest of all American novels; Hawthorne seems to have entered Melville’s life at about chapter twenty-three of the new novel, transforming its tone and ambition.

Again, one is moved to think of a flammable material into which a struck match has been cast, with extraordinary, incendiary results. For Melville was consumed by Hawthorne’s prose style as well as Hawthorne’s tragic vision, which he was to align with the Shakespeare of the great tragedies, and their great soliloquies; the result is a novel that is unwieldy, extravagant, and unique, unsurprisingly dedicated to Hawthorne “in token of my admiration for his genius.” (Moby-Dick was published in 1851, the year of Hawthorne’s The House of the Seven Gables and a year after his Scarlet Letter.) For Melville, this homage to the older writer seems to have constituted the great passion of his life. From a letter to Hawthorne in 1851:

I felt pantheistic then—your heart beat in my ribs and mine in yours, and both in God’s. A sense of unspeakable security is in me this moment, on account of your having understood the book….

Whence come you, Hawthorne? By what right do you drink from my flagon of life? And when I put it to my lips—lo, they are yours and not mine. I feel that the Godhead is broken up like the bread at the Supper, and that we are the pieces. Hence this infinite fraternity of feeling….

The very fingers that now guide this pen are not precisely the same that just took it up and put it on this paper. Lord, when shall we be done changing? Ah! it’s a long stage, and no inn in sight, and night coming, and the body cold. But with you for a passenger, I am content and can be happy. I shall leave the world, I feel, with more satisfaction for having come to know you. Knowing you persuades me more than the Bible of our immortality.

It’s a bitter irony, and must have been a considerable shock to the ecstatic young Melville, that Moby-Dick, in which he had poured his soul, was, to most readers of the era, including even educated reviewers, unreadable—a great classic, we are accustomed to consider it today, and yet a crushing failure to the young writer who would realize only $556.37 from royalties. Reviews were generally negative, some of them savagely so, even in England where Melville’s early South Seas adventure novels were overnight best sellers.

It was unfortunate that Melville’s British publisher brought out the novel before his American publisher, and had not had time to incorporate Melville’s new title, Moby-Dick, which was to replace The Whale; yet more unfortunate that the British publisher failed to include the last page of the novel, which includes the epilogue, and that some of the front matter of the manuscript was moved to the end of the book, as an unwieldy appendix of sorts. It was the case at this time that British publishers could remove from a manuscript anything politically questionable or “obscene”—not only without conferring with the author, but without informing him. On the whole, American reviewers followed British reviewers’ crushing opinions of the novel; not one American reviewer took the time to note that the American edition differed from the British.

Like merely human-sized harpooners surrounding a mighty Leviathan, such crude reviewers had the power to kill the sales of Melville’s books, and to destroy the energies and hope of his youth. He continued to write after Moby-Dick, but never regained his old optimism. Even his attempt to cultivate a new career lecturing to lyceums soon ended when he couldn’t resist mocking the quasi intellectualism and pretention of the lyceum circuit. “Dollars damn me,” Melville said—he had not enough of them.

By the time Melville died, in 1891, even his early best sellers were out of print and his name forgotten. (The account that Melville’s name was printed in the New York Times obituary as “Henry Melville” is evidently not true; but a “Hiram Melville” seems to have crept into print a few days later.) Both his sons had predeceased him, the younger, Malcolm, by his own hand. His marriage seems to have been difficult—his wife’s genteel parents kept urging her to leave him, on the grounds that he was a heavy drinker and insane. It is significant that Melville’s final work of fiction, the posthumously published novella Billy Budd, is a starkly imagined allegory of innocence, evil, and tragic atonement so Hawthornian in its prose and vision that it’s as if Melville’s beloved friend had assisted him a final time.

“Inspiration” in this instance was ravishing, irresistible, a double-edged sword. In the short run, it led to what seems unmistakably like failure, in the author’s tragic experience; in the longer run, great and abiding posthumous success.

She was stalled in a new, ambitious novel, her seventh, that was to be a “study” of provincial English life. (Her most recent novel, Felix Holt, with a similar ambition, had been published two years earlier and had had disappointing sales.) She knew the setting intimately: the Midlands of England, in the 1830s. But after a desultory beginning in 1869, Middlemarch was set aside for a year following domestic distractions; uncharacteristically, the highly professional fifty-year-old George Eliot hadn’t been writing this new novel with much enthusiasm or inspiration.

And then, in May 1870, Eliot and her devoted companion George Henry Lewes visited Oxford, where they had lunch with the rector of Lincoln College and his (conspicuously younger) wife, neither of whom they knew well. The Pattisons were perceived as an oddly matched husband and wife, not only because Francis Pattison was twenty-seven years younger than Mark Pattison but because while Francis was beautiful, lively, and charming, Mark was a “wizened little man” without evident charm, “prone to depression,” a highly private, reclusive scholar of classics and religion.

Clearly, this marriage among unequals made a powerful impression upon George Eliot, who shortly afterward began Middlemarch anew, this time opening with the vivid portrait of Miss Dorothea Brooke: a beautiful, intelligent, and idealistic young woman who makes the grievous error of marrying a much older clergyman-scholar, the pedantic, self-pitying Edward Casaubon. Just as the rector’s young wife Francis had hoped to assist him in his scholarly work, so too Eliot’s Miss Brooke hopes to assist her husband in his quixotic effort to write The Key to All Mythologies.

(Eventually, Francis Pattison would leave her dull, embittered husband, to live in close proximity to a male friend; after years of stoic resignation as Mrs. Edward Casaubon, Dorothea becomes a widow, and remarries, this time a far more suitable man. As Casaubon never completes The Key to All Mythologies, so too Mark Pattison never completed his work of scholarly-historical ambition.)

Deciding to begin Middlemarch not as she’d originally planned, with the young physician Lydgate and the Vincy family into which he marries, but rather with Dorothea (and Casaubon), was indeed inspired, for with this stroke one of the great themes of Middlemarch is forged: the devastation of youthful female idealism under the heavy hand of (patriarchal) convention. Without the impetuous but always sympathetic Dorothea, who, like her American counterpart Isabel Archer (of Henry James’s The Portrait of a Lady, published a decade after Eliot’s novel), makes a very bad mistake in marriage for which she pays dearly, it is difficult to imagine what Eliot would have made of the more conventional characters of Middlemarch. (It is not surprising, however, that George Eliot would always deny having modeled her fictional married couple on the rector of Lincoln College and his young wife. Writers would far rather have us believe that they’ve imagined or invented rather than taken “from life.” In Eliot’s case in particular, with her heightened sense of moral responsibility, she would have felt vulnerable to charges of having exploited the Pattisons, who had befriended her.)

“Try to be one of the people on whom nothing is lost”—this famous admonition of Henry James suggests the nature of James’s own deeply curious, ceaselessly alert, and speculative personality. His inspirations were myriad, and often sprang from social situations, typically for one who “dined out” virtually every night of his adult life. The most frequently recorded of these is James’s inspiration for The Turn of the Screw, which he records in his notebook for January 1895:

Note here the ghost-story told me at Addington (evening of Thursday 10th) by the Archbishop of Canterbury…the story of the young children…left to the care of servants in an old country-house, through the death, presumably, of parents. The servants, wicked and depraved, corrupt and deprave the children…. The servants die (the story vague about the way of it)and their apparitions, figures, return to haunt the house and children, to whom they seem to beckon…. It is all obscure and imperfect, the picture, the story, but there is a suggestion of strangely gruesome effect in it. The story to be told…by an outside spectator, observer.

The “strangely gruesome effect” that most intrigued James was the presence of not one but two ghosts appearing to not one but two innocent children, thus the turn of the screw. It can’t have been accidental that the archbishop’s tale gripped James when, by his account, in his early fifties, he was severely depressed following the public failure of his play Guy Domville (1895), for which he had had great hopes. (Is it a surprise to learn that Henry James, the very avatar of novelistic integrity, the darling of the most mandarin New Critics, in fact had wanted badly to be a popular playwright, and dared to fantasize success in the West End? Imagine poor James’s grief when, at the opening of the play, a section of the audience cruelly jeered him as he stood on stage.)

In this state of mind, the emotionally fragile James was particularly susceptible to the eerie “hauntedness” of the archbishop’s story; he let it gestate for more than two years, then began to write what would be The Turn of the Screw in as entertainingly dramatic and suspenseful way he knew how, to acquire, as he hoped, a new audience in the United States, where sales of his books had languished. Like so much that seems to spring at us from an accidental encounter, The Turn of the Screw had a powerful if perhaps unconscious significance to the author, who claimed, in a letter to a friend, that when he was correcting proofs of the story he “was so frightened that I was afraid to go upstairs to bed.”

What would be a disadvantage for a certain sort of writer, for whom the autobiographical is primary, was for James an enormous advantage: out of the emotional isolation of his bachelor life, imagined by Colm Tóibín in The Master as a life of joyless restraint and denial, James was free to imagine the intense, intimate lives of others. The fascination of the governess of The Turn of the Screw for (sinister, sexual) Peter Quint, for instance, is given a particular charge by James’s particular imagination: homoerotic energies so powerfully repressed that they emerge, they erupt, as agents of unspeakable evil. In this elegantly constructed gothic tale much is ambiguous but the atmosphere of yearning—of desperate, humiliating yearning—is unmistakable. We feel that the emotionally starved young governess is a form of the author himself, helpless in her infatuation with the (sexually charged) ghosts of her own imagination and forced, by this infatuation, to enter the tragic adult world of loss.

Another dinner party gave James the kernel for the gossipy, campy excess of The Sacred Fount.

“Where do you get your ideas?”—the question is frequently asked, and rarely answered with any degree of conviction or sincerity. And rarely is the answer, “A dream.”

Written when Katherine Mansfield was thirty, her short, elliptical story “Sun and Moon” seems to have sprung virtually complete out of a dream. Lyric and fluid like ice melting, a shimmering, impressionistic work of fiction, “Sun and Moon” suggests the haunting evanescence of a dream. In her journal for February 10, 1918, Mansfield wrote:

I dreamed a short story last night, even down to its name, which was “Sun and Moon.” It was very light. I dreamed it all—about children. I got up at 6.30 and wrote a note or two because I knew it would fade…. I didn’t dream that I read it. No, I was in it, part of it, and it played round invisible me. But the hero is not more than five. In my dream I saw a supper table with the eyes of five. It was awfully queer—especially a plate of half-melted ice cream….

Mansfield’s story, for all its delicate filigree, is a chilly prophecy of the destruction of childhood innocence—the “plate of half-melted ice cream” is a little ice cream house that has melted away amid the detritus of an adults’ coarse party from which children are excluded.

The challenge was to write a “ghost story”—so Lord Byron had suggested to his friends, with whom he was traveling in Italy in the summer of 1816; and so Mary Wollstonecraft Godwin Shelley, eighteen at the time, recounts a nightmare:

I saw the pale student of unhallowed arts kneeling beside the thing he had put together—I saw the hideous phantasm of a man stretched out, and then, on the working of some powerful engine, show signs of life…. His success would terrify the artist; he would rush away [hoping] this thing…would subside into dead matter…. He sleeps; but he is awakened; he opens his eyes; behold the horrid thing stands at his bedside, opening his curtains.

Here is a dream vision of singular vividness and strangeness. It would seem almost, by the young writer’s account, that the allegorical horror story or moral parable had not been imagined into being by the author herself. Rather, Mary Shelley is the passive observer; the vision seems to come from a source not herself. Yet we are led to think, knowing something of the biographical context of the creation of Frankenstein, that it can hardly have been an accident that a tale of a monstrous birth was written by a very young woman who’d had two babies with her mercurial and unpredictable poet-lover Percy Shelley, one of whom had died, and was very much pregnant again. And they were not yet married.

Following this dream, Mary Shelley spoke of being “possessed” by her subject. (Though neither Byron nor Shelley responded fruitfully to Byron’s challenge, their companion and friend John Polidori wrote one of the first vampire stories, The Vampyre, published in 1819.) At first Mary Shelley had thought that her lurid gothic tale would be just a short story, but in time, as the manuscript evolved, the work became a curious, heavily Miltonic allegorical romance, rejected by both Shelley’s and Byron’s publishers, who knew that the author was a young woman; and finally published, anonymously, in 1818, when the author was twenty-one. Since then, Frankenstein has never been out of print and is surely the most extraordinary novel ever written by an eighteen-year-old girl.

Today, “Frankenstein” isn’t identified as the doctor-creator of the monster, but the monster himself: the “hideous phantasm.” And Mary Shelley’s brilliantly deformed creation has been detached from the author, an iconic figure seemingly self-generated—one of the great, potent symbols of humankind’s predilection for self-destruction, as significant in our time as in 1818.

Social injustice as inspiration. The wish to “bear witness” to those unable to speak for themselves, as a consequence of poverty, or illness, or political circumstances, which includes gender and ethnic identity. The wish to conjoin narrative fiction with the didactic and the preacherly. Above all, the wish to move others to a course of action—the basis of political, propaganda-art. Here we have such works as Harriet Beecher Stowe’s Uncle Tom’s Cabin, Charles Dickens’s Hard Times, Stephen Crane’s Maggie: A Girl of the Streets, Upton Sinclair’s The Jungle. (Sinclair, an avid lifelong socialist, wrote nearly one hundred books of which the majority are novels involving politics and social conditions in the United States; among these are Oil!, from which the much-acclaimed 2007 film There Will Be Blood was adapted, and the Lanny Budd series of eleven novels, each a best seller when it was published. Dragon’s Teeth was awarded the 1943 Pulitzer Prize.)

Frank Norris’s McTeague and The Octopus are savage critiques of rapacious American capitalism; “class war” might be identified as the groundwork of such novels of Theodore Dreiser as Sister Carrie and An American Tragedy and of John Dos Passos’s hugely influential U.S.A. In the era of Dreiser there were few women writing of life in urban ghettos with the intelligence and emotional power of Anzia Yezierska, whose Bread Givers, Hungry Hearts, and How I Found America: Collected Stories chronicle the lives of Jewish immigrants of New York City’s Lower East Side with unflinching candor.

This is the sort of socially conscious “realistic” fiction that Nabokov scorned as vulgar (“Mediocrity thrives on ‘ideas’”) and of which Oscar Wilde would have said with a sneer, “No artist has ethical sympathies…. All art is quite useless.” Still, mainstream American literature with its predilection for liberal sympathies with the disenfranchised and impoverished, the great effort of the nineteenth- and twentieth-century novel to draw attention to social injustice and inequality, remains the most attractive of literary traditions even in our self-consciously postmodernist era. In Toni Morrison’s Beloved, for instance, slave narrative sources have been appropriated and refashioned into an exquisitely wrought art that is both morally focused and aesthetically ambitious.

From his early novel imaginatively reconstructing the lives of the “atom bomb spies” Ethel and Julius Rosenberg, The Book of Daniel, through the much-acclaimed Ragtime, Loon Lake, World’s Fair, and The March, E.L. Doctorow has taken for his subject the volatile issues of class and race in America; his more recent novels have been shaped by oral histories. “Every writer speaks for a community.”

No one has spoken more explicitly of his political and moral intentions in writing a work of fiction than Russell Banks in his “Envoi” to the novel Continental Drift, which concerns itself, like most of Banks’s fiction, with working-class and disenfranchised Americans caught up in the malaise of a rapacious capitalist economy:

And so ends the story of Robert Raymond Dubois, a decent man, but in all the important ways an ordinary man. One could say a common man. Even so, his bright particularity, having been delivered over to the obscurity of death, meant something larger than itself….

Knowledge of the facts of Bob’s life and death changes nothing in the world. Our celebrating his life and grieving over his death, however, will…. Sabotage and subversion, then, are this book’s objectives. Go, my book, and help destroy the world as it is.

James Joyce once remarked that Ulysses was for him essentially a way of capturing the speech of his father and his father’s friends—an astonishing statement when you consider the complexity of Ulysses, but one that any writer can understand. So much of literature springs from a wish to assuage homesickness, a desire to commemorate places, people, childhoods, family and tribal rituals, ways of life—surely the primary inspiration of all: the wish, in some artists clearly the necessity, to capture in the quasi permanence of art that which is perishable in life. Though the great modernists—Joyce, Proust, Yeats, Lawrence, Woolf, Faulkner—were revolutionaries in technique, their subjects were intimately bound up with their own lives and their own regions; the modernist is one who is likely to use his intimate life as material for his art, shaping the ordinary into the extraordinary.

The confessional poets—Robert Lowell, John Berryman, W.D. Snodgrass, Anne Sexton, Sylvia Plath, to a degree Elizabeth Bishop—rendered their lives as art, as if self-hypnotized. Of our contemporaries, writers as seemingly diverse as Saul Bellow, Philip Roth, and John Updike created distinguished careers out of their lives, often returning to familiar subjects, lovingly and tirelessly reimagining their own pasts as if mesmerized by the wonder of “self.” In his last major, most obsessively self-reflective work, Ada or Ardor: A Family Chronicle, Vladimir Nabokov evokes the intense claustrophobia of a “super-imperial couple” who not only inhabit the same psychic realm but, boldly and audaciously, are intimately related: sister and brother. Set in a whimsical counterworld, “Antiterra,” Nabokov’s commemoration of self is finally, and literally, incestuous.

No writer has been more mesmerized by the circumstances of his own, exceptional life than our greatest Transcendentalist poet, Henry David Thoreau, who wrote exclusively, obsessively of his “self” as an adventurer in a circumscribed world—“I have traveled a good deal in Concord,” as he famously said. Walden is the publicly revered text but it is Thoreau’s Journal, in which he wrote daily from 1837 to 1861, eventually accumulating some seven thousand pages, that is the more remarkable document, as he is the most acute of observers of nature and of human nature; an analyst of his “self” in the Whitmanesque sense, the “self” that is all selves, the transcendent universal. Here is the essential Thoreau, in the essay “Ktaadn and the Maine Woods”:

I stand in awe of my body, this matter to which I am bound has become so strange to me. I fear not spirits, ghosts, of which I am one…but I fear bodies…. Talk of mysteries!—Think of our life in nature,—daily to be shown matter, to come in contact with it,—rocks, trees, wind on our cheeks! the solid earth! the actual world! the common sense! Contact! Contact! Who are we? where are we?

The early Surrealists considered the world a vast “forest of signs” to be interpreted by the individual artist. Beneath its apparent disorder the visual world contains messages and symbols—like a dream? Is the world a collective dream? Not the hypnotic spell of the individual artist’s childhood, family, regional life (as in the inspiration of commemoration) but rather its antithesis, the impersonal, the chance, the “found.” The Surrealist photographer Man Ray wandered Parisian streets with his camera, anticipating nothing and leaving himself open to disponibilité, or availability and chance. The most striking Surrealist images were ordinary images made strange by being decontextualized—“Beautiful as the chance encounter of a sewing machine and an umbrella on a dissecting table” (André Breton appropriating metaphor of Lautréamont).

When photography began to be an art that didn’t depend upon careful staging in a studio, or even outdoors, it was discovered to be ideally suited to the caprices of opportunity; the artist wanders into the world, armed with just his camera, freed from the confines of the predictable and the controlled, as in the work of Henri Cartier-Bresson, Weegee, Bruce Davidson, Garry Winogrand, the newly discovered Vivian Maier, Diane Arbus (whose strategy was “to go where I’ve never been”), and numerous others.

Literature is not a medium that lends itself well to the Surrealist adventure of disponibilité. Even radically experimental fiction requires some strategy of causation, otherwise readers won’t trouble to turn pages. Unlike most visual art, which can be experienced in a single gaze, fiction is a matter of subsequent and successive gazes, mimicking chronological time, as it is locked into chronological time. (A rare exception is William Burroughs’s Naked Lunch with its “cut-up” method of a discontinuous and disjointed narrative appropriate to a drug-addled consciousness, for whom hallucination is more natural than coherence.)

There is a very minor tradition of “found poems” discovered in unpoetic places like newspapers, magazines, advertisements, graffiti, instruction manuals, and brochures. Virtually all poets have experimented with “found poems” at some point in their careers, sometimes appropriating entire passages of prose into a poem, more often appropriating a few lines and constructing a poem around these lines, as in work by Howard Nemerov, Charles Olson, Blaise Cendrars, and Charles Reznikoff among others. A “found poem” gem is Annie Dillard’s appropriation of a manual titled Prehospital Emergency Care and Crisis Intervention (1989) which the poet has fashioned into a suite of short poems titled “Emergencies.”

ANSWER

If death is imminent either

On the scene or in the ambulance,

Be supportive and reassuring

To the patient, but do not lie.If a patient asks, “I’m dying,

Aren’t I?” respond

With something like, “You

Have some very serious injuries,

But I’m not giving up on you.”

More often found poetry is meant to be satirical or witty, or mordantly ironic, as in Hart Seely’s appropriated material titled Pieces of Intelligence: The Existential Poetry of Donald H. Rumsfeld (2003). Here is a complete poem by Rumsfeld/Seely:

THE UNKNOWN

As we know,

There are known knowns.

There are things we know we know.

We also know

There are known unknowns.

That is to say

We know there are some things

We do not know.

But there are also unknown unknowns,

The ones we don’t know we don’t know.

If inspiration is many-faceted, out of what human need—or hunger—does inspiration spring? That’s to say, what is the motive for metaphor?

It seems clear that Homo sapiens is the only species to have anything like language, and certainly the only species to have written languages, “histories.” Our sense of ourselves is based upon linguistic constructs, inherited or remembered, and regarded as precious or at least valuable; our sacred texts are presumed to have been dictated by gods, and sometimes we are fired with murderous rage if these texts are challenged or mocked, or if our creator’s name is uttered in the wrong way, or by the wrong lips. Perhaps literature in its broader sense, incorporating centuries, millennia, as a consequence of myriad individual inspirations across myriad cultures, relates to us as that part of the human brain called the hippocampus relates to memory.

The hippocampus is a small, seahorse-shaped part of the brain necessary for long-term storage of factual and experiential memory, though it is not the site of such storage. Short-term memory is transient—long-term memory can prevail for many decades: the last thing you will be able to retrieve in your memory may well be the first thing that came to reside there—a glimpse of your young mother’s face, a confused blur of a childhood room, a lullaby, a caressing voice. If the hippocampus is injured or atrophied, there will be no further storage of memory in the brain—there will be no new memory. I have come to think that art is the formal commemoration of life in its variety—the novel, for instance, is “historic” in its embodiment in a specific place and time, and its suggestion that there is meaning to our actions. It is virtually impossible to create art without an inherent meaning, even if that meaning is presented as mysterious and unknowable.

Without the stillness, thoughtfulness, and depths of art, and without the ceaseless moral rigors of art, we would have no shared culture—no collective memory. As if memory were destroyed in the human brain, our identities corrode, and we “were” no one—we become merely a shifting succession of impressions attached to no fixed source. As it is, in contemporary societies, where so much concentration is focused upon social media, insatiable in its fleeting interests, the “stillness and thoughtfulness” of a more permanent art feels threatened. As human beings we crave “meaning”—which only art can provide; but the social media provide no meaning, only this succession of fleeting impressions whose underlying principle may simply be to urge us to consume products.

The motive for metaphor, then, is a motive for survival as a species, as a culture, and as individuals.