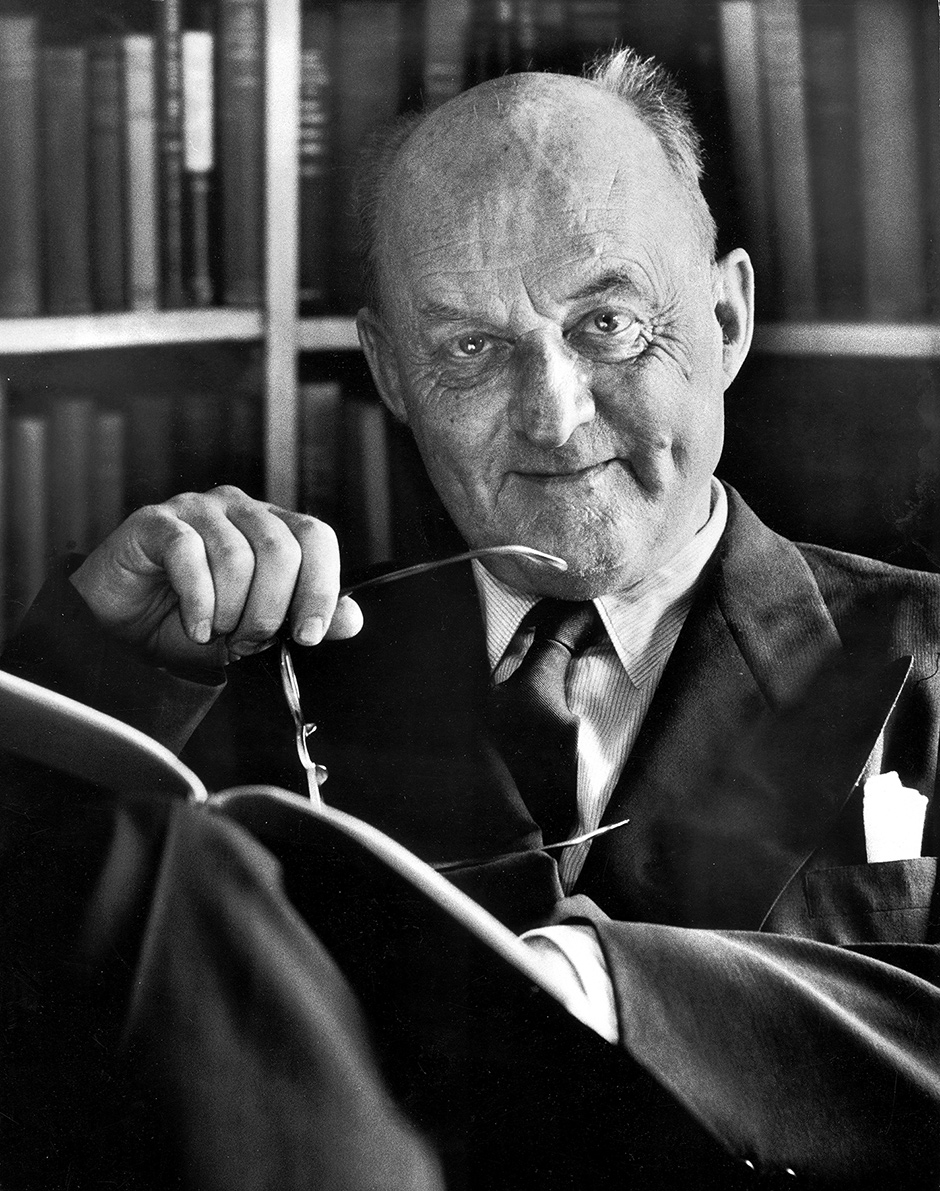

This selection of Reinhold Niebuhr’s work, edited by his daughter Elisabeth Sifton, is the 263rd volume in the Library of America; and it is possible that the single sentence that appears on page 705 is known to more people, and has affected them more deeply, than anything else the library has ever published:

God, give us grace to accept with serenity the things that cannot be changed, courage to change the things that should be changed, and the wisdom to distinguish the one from the other.

This is the original version of what has come to be known in many slight variations as the Serenity Prayer, under which name it can be found in millions of American homes in every medium imaginable—posters, refrigerator magnets, placemats, even tattoos (the Internet offers dozens of examples). Much of this popularity is owed to Alcoholics Anonymous, which adopted Niebuhr’s prayer as an official meditation.

Surely most of the people who have turned to the Serenity Prayer in times of trouble know little about the man who wrote it. Niebuhr’s achievements as an intellectual, his influential contributions to public debate from the post–World War I years through the cold war and the civil rights movement, his reputation as a liberal thinker and activist, even his status as President Obama’s favorite theologian—these do nothing to cement the authority of the prayer, which stands on its own as a piece of seemingly timeless wisdom. Yet it is possible to read the whole of Niebuhr’s thought through the lens of the Serenity Prayer, which is a more complicated and challenging text than it may first appear.

Despite its name, it is not a prayer for serenity alone—it could just as well be called the Courage Prayer or the Wisdom Prayer, virtues that Niebuhr sees as equally important, and indeed indispensable to the achievement of serenity. Far from being a call to resignation, or a permission slip for turning over one’s problems to God, the prayer is actually an acceptance of responsibility. It is up to each individual to examine himself and the world, and to find out how much they need to be and can be changed. It is only when the limits of this change are reached that we are allowed the consolation of serenity. The Serenity Prayer is actually a prescription for a strenuous moral life.

This strenuosity, this refusal of easy religious and political answers, this insistence on responsibility in thought and action, is the hallmark of Niebuhr’s thought. “An adequate religion,” he wrote in a sermon, “is always an ultimate optimism which has entertained all the facts which lead to pessimism.” Here, and throughout this book, Niebuhr’s message is in the first instance political and social. Over the decades of his active career, Niebuhr confronted public “facts which lead to pessimism” again and again. After World War I, the Versailles Treaty betrayed Niebuhr’s trust in Woodrow Wilson’s promises of a new world order. During the 1920s, as a pastor in a church in Detroit he saw how American prosperity was built on the backs of the industrial proletariat. When the Depression came, Niebuhr, like many others, saw some sort of Marxist revolution as both inevitable and justified. During the early years of World War II, he feared that American isolationism would ensure the triumph of Nazism; and during the cold war, he dreaded the threat of communism even as he warned against the arrogance of American power.

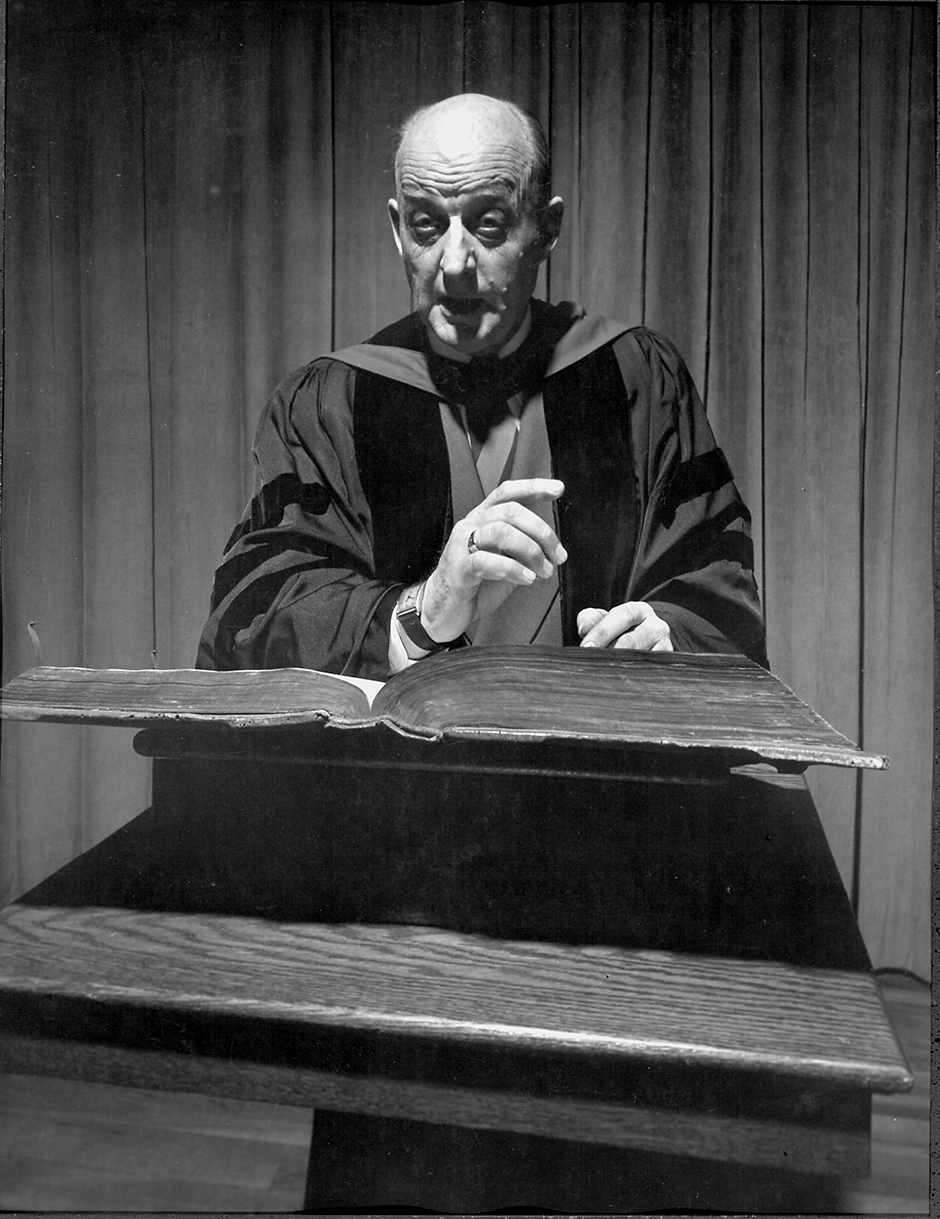

This list of topics sounds like the agenda of a pundit more than of a theologian, and it is often possible, when reading Niebuhr, to momentarily forget that we are hearing the voice not just of a public intellectual, but of a pastor. To Niebuhr himself, however, there was no contradiction between these identities. And as soon as he turns from the issues of the day to his deepest convictions about history and ethics, it becomes clear that the values we associate with Niebuhr even today—responsibility, moral complexity, a sense of human evil, hope tempered by humility—are best understood within the setting of his Christian faith. That is why the most revelatory section of the Major Works is the selection of sermons and prayers that follows the famous books. When Niebuhr prays, “Show us what we ought to do. Show us also what are the limits of our powers and what we cannot do,” it becomes clear how the personal insight of the Serenity Prayer and the political insight of The Irony of American History are both underwritten by faith in a God who can, and sometimes does, allow us to transcend our limits.

The profile of the Christian intellectual has changed greatly since Niebuhr’s time. In the US, notwithstanding the pope’s emphasis on the poor and the outcast, Christian politics today are often understood to be synonymous with right-wing politics, especially when it comes to social issues like abortion and gay marriage. These positions are ostensibly rooted in biblical fundamentalism, which also continues to challenge mainstream scientific understanding of evolution and even global warming. But Niebuhr’s kind of liberal Protestantism inhabits a very different spiritual universe, in which Christianity is the basis not of certainties but of productive, ongoing doubts. He prefers questions to answers, and the wisdom to be gained from reading him is not a set of dogmas but a habit of mind, a way of looking at the self and the world.

Advertisement

The foundational doubt in Niebuhr’s work is whether, and how, Christianity can be a force for justice in this world. He believed profoundly that it must, and yet he never underestimated the obstacles. First, the theological obstacles: in the gospels, Jesus preaches a radically otherworldly and self-sacrificing ethics, in which the Christian is commanded to turn the other cheek and render unto Caesar. Niebuhr was never truly attracted by this kind of passivity, perhaps because the mystical and millennial aspects of religion had so little appeal for him. A rationalist and a progressive, he tended to find in Jesus not a personal promise of redemption, but a symbol of God’s power to transform human life. Rather than saying that Jesus is God, Niebuhr preferred “to define him by saying that ‘God is like Jesus.’”

As he confesses in Leaves from the Notebook of a Tamed Cynic, his 1929 memoir of his years as a pastor in Detroit, this approach did not always win favor with more literal-minded believers. “The old gentleman was there too who wanted to know whether I believed in the deity of Jesus,” he writes about one meeting of ministers in 1925. “He is in every town. He seemed to be a nice sort, but he wanted to know how I could speak for an hour on the Christian church without once mentioning the atonement.”

Niebuhr nicely turns the question around, replying, “I believed in blood atonement too”—by which he meant the act performed once and for all by Jesus, when he shed his blood for the redemption of mankind—“but since I hadn’t shed any of the blood of sacrifice which it demanded I felt unworthy to enlarge upon the idea.” This characteristically broadens the idea of atonement from a metaphysical act into a moral act, in which all who profess Jesus must share. Throughout his work, Niebuhr rarely if ever sees Jesus as repaying the debt mankind incurred through original sin; rather, he imagines Jesus as a perpetual reminder that the debt is still owed.

By the same token, the idea that people—especially those Niebuhr calls, with biblical resonance, “the disinherited”—should sacrifice worldly hopes in the name of a heavenly reward seems to strike him as not just unfair but hopelessly naive. “Whenever religious idealism brings forth its purest fruits and places the strongest check upon selfish desire,” he writes in Moral Man and Immoral Society, “it results in policies which, from the political perspective, are quite impossible.” For example, in his view pure pacifism in the face of attack by murderous dictators would make no sense.

This explains the dualism of the title of this book, his most radical statement, published in 1932 at the nadir of the Depression. It may be possible to expect a human being to be genuinely selfless and good in his or her family life and personal relationships. But it is simply not in human nature for these virtues to be translated into the larger, impersonal scale of an entire country or an entire world. “It would therefore seem better to accept a frank dualism in morals,” Niebuhr concludes, which would “distinguish between what we expect of individuals and of groups,” since “the moral obtuseness of human collectives makes a morality of pure disinterestedness impossible.”

This hardheaded analysis leads directly to the second kind of obstacle that Niebuhr confronts, this time not theological but practical. How is the Christian minister, who in his view ought to be an activist and a goad to action, to convince his congregants that faith should be not just professed but lived? This is the central question of the Notebook, which is unique among Niebuhr’s books for its personal approach and avoidance of abstract arguments. In 1915, after graduating from Yale Divinity School, the twenty-three-year-old Niebuhr accepted a call from Bethel Evangelical Church in Detroit, part of the German Evangelical Synod in which he had been raised (and in which his own father had been a pastor). Over the next thirteen years, even as Niebuhr traveled extensively and earned a national reputation with his writing, Bethel was his base of operations, and it offered a fascinating window onto a city that was growing and modernizing at a breakneck pace. Niebuhr’s own church grew in tandem with the city, and kept up with the times in many ways—notably, dropping German for English as the language of prayer.

Advertisement

Yet when it came to questions of social and racial justice—for instance, the rights of labor in Henry Ford’s massive factories—Niebuhr found his public harder to move. “The new Ford car is out. The town is full of talk about it,” he writes acidly in his notebook in 1927. “I have been doing a little arithmetic and have come to the conclusion that the car cost Ford workers at least fifty million in lost wages during the past year.” But how to inspire his flock with a sense of righteous injustice, when they were flourishing under the status quo? “The gospel commits us to positions which require heroic devotion before they will ever be realized in life. But we are astute rather than heroic and cautious rather than courageous,” he reflects, and characteristically Niebuhr includes himself in his own indictment. In 1928, about to leave Bethel for Union Theological Seminary in New York, where he would spend the rest of his career, he notes: “Here I have been preaching the gospel for thirteen years and crying, ‘Woe unto you if all men speak well of you,’ and yet I leave without a serious controversy in the whole thirteen years.” Niebuhr took to heart the lesson that “it is almost impossible to be sane and Christian at the same time,” and regretted that “on the whole I have been more sane than Christian.”

By the time he came to write Moral Man and Immoral Society, Niebuhr had arrived at the conclusion that Christianity was proving an alibi for inaction rather than a creed of change. This explains the militantly confrontational tone of much of the book, whose primary audience and target was moderate socialists. Niebuhr had run for Congress on the Socialist ticket in 1932, but he came to believe that religious progressives believed too much in individual changes of heart, not enough in systemic transformation.

In some of the most unsettling parts of the book, Niebuhr seems to come out in favor of violent revolution. He wrote with cool relentlessness:

If a season of violence can establish a just social system and can create the possibilities of its preservation, there is no purely ethical ground upon which violence and revolution can be ruled out.

But if this ends-justify-the-means rhetoric sounds odd coming from the minister of a religion of peace, by the end of the book Niebuhr has retreated from it somewhat. In theory violence might be justified, he argues, but in practice the American proletariat has no more chance of winning a revolutionary struggle than do American blacks. For both of these “disinherited” groups, Niebuhr concludes, confrontational nonviolence on the Gandhian model is the best course: “Non-violence is a particularly strategic instrument for an oppressed group which is hopelessly in the minority and has no possibility of developing sufficient power to set against its oppressors.”

By the time Niebuhr published the next book included in the Library of America volume, The Children of Light and the Children of Darkness, in 1944, history had convinced him that the Marxist analysis of Moral Man was incorrect. Above all, the course of events in Soviet Russia had shown that communism was not in fact a cure for the problems of human society. The abolition of property, which in 1932 had seemed like a necessary first step toward reconstruction, now struck Niebuhr as simply another illusionary solution to the perpetual problem of human society, which was human selfishness. “There is no basis for the Marxist hope that an ‘economy of abundance’ will guarantee social peace; for men may fight as desperately for ‘power and glory’ as for bread,” he observes.

At this stage, Niebuhr was still willing to group liberals and Communists together as “children of light,” as against the outright barbarism of the Nazi “children of darkness.” But he chastised both groups for naively believing that society could ever be made perfect. Sounding much like Isaiah Berlin or Lionel Trilling, other great liberal pluralist thinkers of the same moment, Niebuhr advocated for a modest recognition that there is no permanent solution to human difficulties: “It is an illusion of idealistic children of light to imagine that we can destroy evil merely by avowing ideals.” Where Berlin rooted his conclusions in political philosophy and Trilling rooted his in literature, however, Niebuhr found support in religion, and particularly in the idea of original sin, which he called “the understanding of the Christian faith that the highest achievements of human life are infected with sinful corruption.” His religious vocabulary allowed him to speak unembarrassedly about evil as a real and permanent force in human life, in a way that American liberals traditionally did not.

For Niebuhr, the failure of naive optimism about human society was not a reason for despair or pessimism. Indeed, the typical motion of his thought is to posit a binary analysis—optimism or pessimism, light or darkness, idealism or cynicism—and then to discredit it in favor of some kind of synthesis. “The children of light must be armed with the wisdom of the children of darkness but remain free from their malice,” he concludes. This approach sometimes leads Niebuhr to sound too dismissive of thinkers whom he uses as representatives of one “side,” as when he breezily rebukes “the pessimism of such men as Thomas Hobbes and Martin Luther.”

As his critics noted during his lifetime, Niebuhr’s strength was not historical or philosophical expertise, or literary grace—his prose has many of the vices George Orwell warned against, with too many Latinate words, passive constructions, and abstractions, and a lack of striking, concrete imagery. As his biographer Richard Wightman Fox makes clear, Niebuhr wrote too much and too fast to pay attention to questions of style. (The present volume, at nearly one thousand pages, represents only a part of his output, notably omitting his most ambitious work, The Nature and Destiny of Man, based on his Gifford lectures of 1939.)

Rather, Niebuhr’s strength as a writer comes from his persistent return to the same complex of ideas and problems, even as the circumstances of his thought changed. The Marxist revolution that looked desirable to him in 1932, and still understandable in 1944, had become anathema by 1952, when he published The Irony of American History. By that time, the surprising resilience of American democracy had increased Niebuhr’s respect for a system he once saw as doomed. The preacher who inveighed against the class system in the 1920s can now be found writing, “The prosperity of America is legendary. Our standards of living are beyond the dreams of avarice of most of the world.” It was not that poverty and injustice had disappeared, but Niebuhr now saw them as remediable within a capitalist democracy:

We have managed to achieve a tolerable justice in the collective relations of industry by balancing power against power and equilibrating the various competing social forces of society.

At the same time, the spectacle of Stalin’s Soviet Union had amply confirmed the danger that Niebuhr had warned against as early as Moral Man, that the abolition of property would simply translate power struggles into a new and even more dangerous register. Writing at the peak of anti-Communist fervor in America, Niebuhr now refers to communism as “demonic” and “satanic,” and sees the cold war as a clear struggle of “freedom against tyranny.” Yet The Irony of American History, as its title makes clear, is no paean to the country whose “side” Niebuhr unambiguously takes. Rather, under changed historical conditions, he is once again applying the lessons of his Christian liberalism, which sees the chief threat to the good precisely in its own certainty of goodness. “God and the devil may be in conflict on the scene of life and history, but a victory follows every defeat and some kind of defeat every victory,” he had written as long before as 1924, in his Notebook. Now he set out to remind a victorious and prosperous America of this truth.

Once again, he called on his readers to thread the needle of a binarism. On the one hand, he warned against a return to pre-war isolationism, now that an aggressive Soviet Union had taken the place of Nazism as a threat to world peace. The isolationist, he argued, succumbed to the temptation to “preserve our innocence” by abstaining from geopolitics, out of an unspoken conviction that “power cannot be wielded without guilt.” On the other hand, there is the traditional American temptation to believe that the country remains radically innocent even when exercising its power, that America’s good intentions mean all its actions are praiseworthy. “We are (according to our traditional theory) the most innocent nation on earth,” he writes, and he does not mean this as a compliment.

For the hallmark of maturity, in nations as in individuals, is to recognize that no use of power is fully innocent, that every decision involves the sacrifice of one value to another. This does not mean that power shouldn’t be used—Niebuhr has no doubt that America must defend the West against communism—but it does mean that it should be used thoughtfully and humbly. “The ironic elements in American history can be overcome,” he writes,

only if American idealism comes to terms with the limits of all human striving, the fragmentariness of all human wisdom, the precariousness of all historic configurations of power, and the mixture of good and evil in all human virtue.

Exactly what this means in practice is, of course, difficult to say. Earlier this year, when President Obama made a speech comparing ISIS’s barbarism to that of the Christian Crusaders of the Middle Ages, Ross Douthat of The New York Times identified it as a classic Niebuhrian moment, a case of power submitting to self-criticism by referring to the past behavior of one’s own forebears. Better to attend to the mote in your own eye, Obama appeared to be saying, than to the beam in your neighbor’s eye. This line of argument tends to support Obama’s reluctance to use American power to impose order on the Middle East—an enterprise that the Iraq war revealed as a typical instance of hubristic American “innocence.”

Yet it would also be possible to make a Niebuhrian argument in favor of American intervention in places like Iraq and Syria, by dwelling on the part of his message that emphasizes the responsibility of power—the need to act even if action is imperfect and has unintended consequences. (The Irony of American History ends by praising Lincoln, whose deeply ironic understanding of the Civil War, as advanced in the Second Inaugural, did not stop him from waging that war with overwhelming violence.) That is why so many people end up dissatisfied with the kind of liberalism Niebuhr preached: it offers no easy guide to action, nothing to relieve us of the burden of choice. Of course, that is precisely why it was the message Niebuhr thought Americans needed to hear. Reading his work today, amid our own challenges of social inequality and imperial hubris, suggests we still need it as much as ever.