When Léon Blum became president of the Council of Ministers of France—in effect, prime minister—on June 6, 1936, a world was turned on its head. He was the first socialist ever to occupy that position in France, and the first avowed Jew to head a major modern government anywhere (Benjamin Disraeli had converted at the age of twelve to the Church of England). Many admired his creative leadership of the Popular Front government from June 1936 until June 1937. Others reviled him almost hysterically as the embodiment of the “Judeo-Bolshevik peril.” He left no one indifferent.

Pierre Birnbaum, a French political sociologist who has written prolifically and with authority about the place of Jews in French politics and administration, along with the anti-Semitic reaction to their success, has given more attention to Blum’s Jewishness than earlier major biographers such as Joel Colton and Jean Lacouture. This is only to be expected of a volume in Yale University Press’s Jewish Lives series. But even if Blum had wished to play down his Jewishness, his enemies would not have let him. On the day that the French Chamber of Deputies voted Blum into office, Xavier Vallat, deputy from the Ardêche, rose to regret that “this old Gallo-Roman country” was going to be governed by a “subtle Talmudist.” Vallat was to become in 1941 the Vichy regime’s first commissioner for the Jewish problem (commissaire aux questions juives).

Blum affirmed his Jewish identity proudly whenever he felt it was scorned. Significantly, he referred to himself provocatively as a Juif, rather than the politer Israélite, the term preferred by those who thought of themselves as French citizens coincidentally of Jewish background (e.g., Proust’s Charles Swann). Born in Paris to a middling commercial family that had left Alsace in the 1840s, he was raised observant and always professed respect for Jewish traditions, though as an adult he ceased to practice most of them. Birnbaum notes that he did not have his son circumcised.

Although his three wives were Jewish, only the first marriage was celebrated in a synagogue (the third was enacted while he was under house arrest in Germany in 1943). He gratefully thanked an admirer for sending him “a lovely ham hock” when he was in a Vichy French prison. Jewishness became for him less a theological position than a commitment to social justice. It meant loyalty to a family heritage plus a set of moral values closely aligned with the universalist, rationalist progressivism of the French republican tradition. It identified Judaism closely with the legacy of the French Revolution (that had, after all, made, for the first time, citizens of the Jews living in France).

Birnbaum also shows that, unlike most assimilated French Jews, Blum supported Zionism, despite its potential conflict with French assimilationist universalism. His was a “philanthropic Zionism” intended to aid the victims of pogroms elsewhere; he did not expect any French Jew to emigrate. In a rare critical passage, Birnbaum shows that Blum considered Arab-Jewish frictions a transitory matter of class conflict between Arab landlords and poor Jewish settlers whose homeland would be set “apart from other parts of Palestine.” Later, in 1948, Blum had a major part in bringing about French recognition of Israel. A kibbutz was named for him by its American founders in 1943.

Birnbaum spends less time on Blum’s socialism, but this was almost as complicated as his Jewishness. The young Léon started out as a literary critic and dandy, in touch with Proust and Gide. The Dreyfus Affair drew him into politics in the orbit of the socialist leader Jean Jaurès. At first Blum studied law and became a judge in France’s highest administrative law court, the Conseil d’Etat. During World War I he served as an administrative assistant to Marcel Sembat, a socialist politician with a seat in the war cabinet. There he acquired a taste for government. He won a seat in the Chamber of Deputies in 1919, which required him to resign his position on the Conseil d’Etat, but he retained a lawyerly view of social reform, believing that wider use of contractual relationships would help resolve French social and economic problems.

Being a French socialist, however, had almost as many rules, rituals, and conventions as being a French Jew. The French Socialist Party remained officially committed to finishing the revolutionary project initiated in France in 1789 even longer than the German Socialist Party did (the British Labour Party was always more pragmatic). It professed goals of social revolution and the abolition of capitalism until the time of François Mitterrand, long after its actual practice had become reformist. Blum was a crucial figure in the long and hesitant transition of the French Socialist Party into a party of government.

French socialists had long refused to become ministers in a bourgeois government. A controversial exception had been made during the Dreyfus Affair, with Alexandre Millerand as minister of commerce in 1899, and again during World War I, but such departures could be justified when the Republic seemed in danger. Only in 1924, when the Cartel des Gauches (a center-left coalition) came to power, did the Socialist Party decide for the first time to vote as a group in support of a bourgeois government. Even then, socialists always voted against any and all military appropriations. When Blum accepted government responsibility for his party in 1936 he needed to explain to his militants, with his usual legal scrupulousness, that this was an “exercise of power” and not yet a “conquest” of it.

Advertisement

French socialism had been split in two in the aftershock of the Bolshevik Revolution. At the party congress at Tours, in 1920, a majority, not wishing to miss the train of world revolution, voted to join Lenin’s Third International. Blum emerged as the leader of the remainder that explicitly rejected Lenin’s requirement that the French Socialist Party purge its reformists and create a tightly centralized and actively subversive party. After Jaurès was assassinated in 1914, Blum successfully assumed his mantle as the leader of reformist parliamentary socialism in France—embodied officially in the French Section of the (Second) Workers’ International—until his death in 1950. Though officially Marxist, the otherwise widely curious Blum spent as little time with Marxist exegesis as with the minutiae of Jewish law or practice.

Birnbaum calls Blum a “state Jew,” a term of his own devising that echoes the “court Jews” of earlier centuries.1 In this sense, Blum fulfilled his Jewishness in a career of public service to progressive causes within the French Republic. The Marxist view of the state as an instrument of capitalist domination was unthinkable for him, since he viewed the French state as a neutral agent for the public good. It has been one of Birnbaum’s contributions to scholarship to demonstrate the prominent role that French Jews took in academia and state service in France after the foundation of the Third Republic in 1875.

This contrasted conspicuously with the total exclusion of Jews from the faculties of major American universities at that time, and their limited role in the American judiciary and public administration.2 There were even Jewish generals in the French army (as there were in the American army) at the very moment in 1894 when a trainee in the General Staff, Captain Alfred Dreyfus, was falsely accused of being a German spy. France was engulfed for a decade in a raging quarrel over this injustice before Dreyfus was finally exonerated. Thereupon French anti-Semites began to attack the regime itself as a “Jewish Republic.”3 Only the “national union” of World War I tempered this anti-Semitic surge.

After recovering some degree of calm and prosperity in the late 1920s, the French Third Republic faced three challenges in the 1930s that threatened its very existence. Germany revived and rearmed after January 1933 under the leadership of Adolf Hitler, determined to avenge the defeat of 1918. The world depression that began with the October 1929 stock market crash in New York affected France late, but lasted longer there than elsewhere because successive French governments tried to cure it by austerity. Prime Minister Pierre Laval went so far in his desperate effort to balance the budget in 1935 as to cut all government expenses, local and central, by an arbitrary 10 percent, and wages and salaries of all government employees by up to 10 percent. The result was a dispiriting economic slump that exacerbated social conflict.

Thirdly, as a country that had earlier encouraged immigration to provide the workers and soldiers that its own low birth rate failed to supply, and as one traditionally hospitable to refugees, France became the destination of choice for Jews fleeing Nazi violence. France received proportionally more Jewish refugees in the 1930s than the United States, which, notoriously, declined to modify the system of national quotas it had adopted in 1922. Many French people came to believe that the refugees took jobs away from French workers, refused assimilation to French language and culture, and promoted war against Hitler. By 1936 successive centrist French governments had dealt poorly with all three problems. The Germans had reoccupied the Rhineland, the economy had shrunk, and France seemed filled with unwelcome and ungrateful foreigners.

Promising sweeping change, a new left-wing coalition, the Popular Front, won the elections of April–May 1936. The Popular Front was an ill-assorted mixture. On the conservative end stood the big center-left Radical Party. Its name was an anachronism, for its positions had ceased to be “radical” by 1900. It represented small property owners and professionals in country towns, and thus was conservative on economic issues, while still seeing itself as “left” in defense of the Republic against the Catholic Church and other enemies on the right.

Advertisement

At the left end of the Popular Front stood the Communist Party, now liberated by Stalin, finally alive to the Nazi threat, from its sterile opposition to the reformist left. The economic goals of the three parties were in conflict, but they were pulled together by a desire to defend the French Republic against fascism. United mainly by this political cause, they found themselves obliged to deal primarily with economic depression.

It fell to Léon Blum to head the new government, for his Socialist Party had become the largest of the three constituent parties of the Popular Front coalition. Among his problems was a belief by some French workers that the revolution was at hand. France’s largest strike wave until 1968 led to the occupation of many factories and farms, more in celebration than in anger (workers danced in the occupied premises). Terrified employers, meeting overnight in Blum’s offices in the Matignon Palace, agreed to fundamental reforms that permanently transformed French working lives: a forty-hour work week, two weeks of vacation with pay except in small shops, and the workers’ right to organize and bargain collectively with their employers. A government-regulated wheat market was intended to reverse the collapse of farm income and a 15 percent pay raise was designed to stimulate workers’ purchasing power, in contrast to previous governments’ policies of deflation and balanced budgets. Appointing the energetic reformer Jean Zay as minister of education, Blum raised the school-leaving age from twelve to fourteen, and proposed steps to broaden access to secondary education, where the classical curriculum of the prestigious lycées had hitherto restricted social mobility.

The Popular Front ran out of steam, however, before these measures could get beyond the exploratory stage. Blum offered assurances that he would govern within the existing capitalist system while trying to moderate its harshness. When the Communist leader Maurice Thorez proclaimed that one must know how to terminate a strike, the “revolution” was over.

After that epoch-making beginning, the rest of Blum’s year at the head of the Popular Front government was, by almost all accounts, a failure. Economists have charged him with doing both too much and too little. The reasons for failure, however, lay partly outside Blum’s control. Humiliated by the workers dancing in their premises, the employers did everything possible to claw back their prerogatives. They applied the forty-hour week in a way that limited operations to a single shift; production fell, unemployment persisted, and deficits increased in both the budget and the balance of international payments. Since Blum felt unauthorized to impose exchange controls, French capital fled abroad while the international currency market punished the franc. Inflation returned. Breaking an earlier promise, Blum devalued the franc in October 1936, too little and too late to improve exports and reverse capital flight. In February 1937 he was obliged by poor economic conditions to declare a “pause” in his social and economic programs.

The foreign situation was even worse. On July 18, 1936, the Spanish general Francisco Franco ferried troops from Spanish Morocco to the mainland in planes lent by Mussolini, in a move to overthrow the Spanish Republic. The Spanish civil war tore the Popular Front coalition apart. Blum and the Communists wanted to help the sister republic in Madrid while the Radicals (and the British) were adamantly opposed. The ever-scrupulous Blum limited the French role to some clandestine aid and an ineffective arms blockade. When six antifascist protesters were killed by French police in March 1937, the government seemed to be devouring its own base. In June Blum resigned after the Senate rejected a measure to grant him special powers. The Popular Front coalition continued nominally to govern for a time under other prime ministers, but the experiment was over.

Blum’s time in office left some lasting legacies. His reforms of working life became the foundation of the postwar social contract in France, as did his innovations in government support for the arts and for sports. The Socialist Party, previously uninterested in the economics of repairing capitalism, began by 1938, when Blum headed another very brief government, to study Keynes. Blum also broke the socialist taboo against providing arms for military forces, and, for the first time since the early 1930s, the defense budget grew. But the Popular Front experience deepened a debilitating political polarization that had begun with the right-wing attempt to march on the Chamber of Deputies on February 6, 1934. Blum was vilified publicly to a greater degree than any other French political leader in modern times. The virulence of invective against him from the right, and, indeed, the far left, is astonishing to read today.

With the incoherence of anti- Semitism, he was accused simultaneously of fomenting revolution and dining on golden plates. He was said to have been born somewhere in Eastern Europe with the real name of Karfunkelstein. His enemies asserted that he hated France and wanted to destroy it. The famous phrase “better Hitler than Blum” is no fiction (I once found in the German archives a report by the German consul in Luxemburg, from the fall of 1936, quoting two deputies of the Meurthe-et-Moselle department saying just that). If there was any one issue that united the disparate coalition of reactionaries, pacifists, and technocratic modernizers that formed around Marshal Pétain and the Vichy regime after June 1940, it was a desire to get revenge for the “Popujew Front.”

Blum was in physical danger after the German victory over France in June 1940. He had already been beaten in the street by a right-wing crowd in February 1936, and Charles Maurras had been sentenced to four months in prison for publicly advocating Blum’s murder in his newspaper Action française. Vichy arrested Blum and put him on trial for causing the defeat of France, but he defended himself so ably that the trial was adjourned sine die. In 1943 the Germans took him from his Vichy prison and interned him in a hunting lodge adjacent to the Buchenwald concentration camp, though he remained totally ignorant of conditions inside. As the Allied armies approached, he was moved to Dachau and then south through Austria, and was liberated only in May 1945.

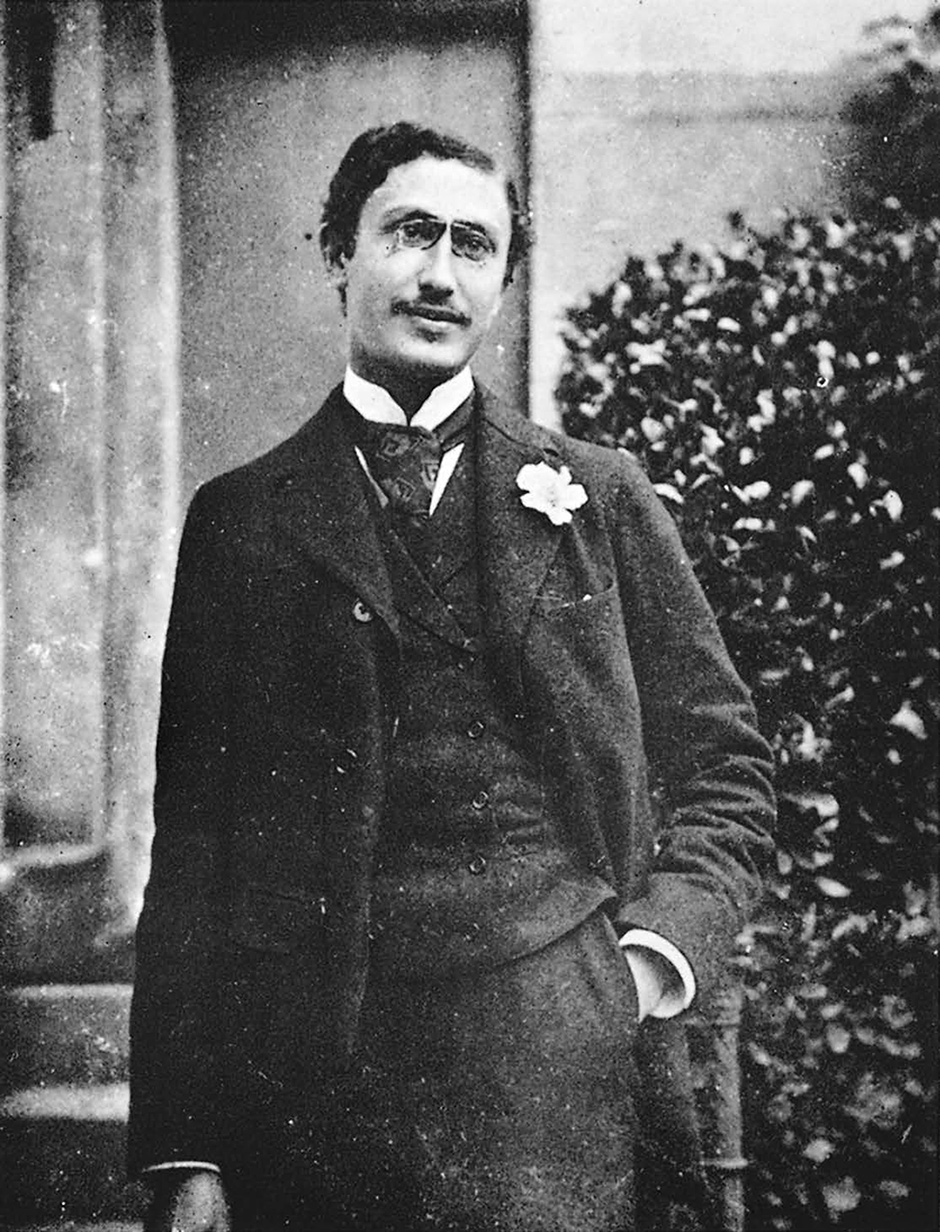

Léon Blum has been an attractive subject for biographers. Warm, sociable, articulate, he excelled in three demanding careers. Birnbaum says relatively little about his work as a literary critic, but he was part of the brilliant assimilated Jewish intelligentsia of the turn of the century. The book’s frontispiece photo of this willowy youth (see illustration on this page) makes it hard to envision the decisive and courageous leader he became thirty years later. As a politician this refined intellectual seems incongruous as the much-appreciated representative of small-holding winegrowers around Narbonne, in southern France. Blum had indeed first represented a Paris district, but the Communists evicted him from that seat in 1928 by maintaining their candidate in a run-off, splitting the left vote much as Ralph Nader was to do in the US in 2000.

Birnbaum’s biography thus follows many others. It is the most concise of the authoritative biographies (sometimes too much so for readers not fully familiar with the background, but he worked within a constricting page limit). It also makes clearer than the others how fully Blum assumed his Jewish identity, though in a rationalist, universalist, and civic form that was essentially secular. Finally, Birnbaum’s biography is the most personal so far, a “portrait.” The willowy youth turned out to be physically courageous (he fought a duel in 1912), and powerfully attracted to women. Birnbaum reveals more than any other biographer about Blum’s marriages and extramarital affairs, drawing upon his private correspondence.

These letters have a curious history of their own. The Nazis seized them when they stripped Blum’s Paris apartment during the occupation. The Russians found the Blum archive in Berlin in 1945 and took it home to Moscow as war booty, along with additional French archives seized by the Nazis. The entire trove was returned to France for what is rumored to have been a considerable payment only in the 1990s. Birnbaum’s unrivaled knowledge of French politics, French Judaism, and French anti-Semitism make his book a totally reliable and highly readable introduction to a rich life.

Despite his verbal commitment to an eventual socialist revolution that he probably always meant to be peacefully incremental, Blum’s most direct inspiration was Roosevelt’s New Deal (similarly attacked at home as the “Jew Deal”). American Ambassador William C. Bullitt reported to FDR on November 8, 1936, that Blum had come in person to congratulate the president on his reelection, declaring that it strengthened his own effort to “do what you have done in America.” Bullitt described the French prime minister bounding up the embassy steps, tossing his habitual broad-brimmed black hat to a butler, and kissing the ambassador’s cheeks. Bullitt called it “as genuine an outpouring of enthusiasm as I have ever heard.”4 A Blum–Roosevelt comparison cannot be taken far, however. Roosevelt had decisive advantages: election to a full four-year term; firm support from a majority in Congress; a lower level of internal protest; and peace on his doorstep, at least at the beginning. Finally the American economy was large enough to take its own steps without fatal international retaliation.

Readers today may well perceive more parallels with a more recent American president elected in euphoria but struggling afterward to govern amid political polarization, whose exotic name and allegedly foreign birthplace and supposed lack of American patriotism are constant themes in the conservative media. Blum may have been the French Obama rather than the French Roosevelt.

-

1

Pierre Birnbaum, The Jews of the Republic: A Political History of State Jews in France from Gambetta to Vichy, translated by Jane Marie Todd (Stanford University Press, 1996). ↩

-

2

Birnbaum has explored this comparison deeply in Les Deux Maisons: Essai sur la citoyenneté des Juifs (en France et aux Etats-Unis) (Paris: Gallimard, 2012). ↩

-

3

Pierre Birnbaum, Un Mythe politique: “La République Juive,” de Léon Blum à Pierre Mendes-France (Paris: Fayard, 1988). ↩

-

4

Joel Colton, Léon Blum: Humanist in Politics (Knopf, 1966), p. 161n. ↩