Many Americans were drawn into political activism during the 1960s, and many became dissatisfied with the established and accepted means of protest. By the end of the decade, such doubts were widespread in both of the great overlapping movements of the time. Opponents of the Vietnam War could tell themselves they had unseated a president, Lyndon Johnson, and helped turn public opinion around. But the war continued, and when the Moratorium demonstrations of November 1969 brought half a million protesters to Washington, the new president, Richard Nixon, told the country that he would “under no circumstances…be affected whatever” by such actions.

In the pursuit of justice for African-Americans, the way forward was also unclear. Hard-won legal and legislative victories had failed to deliver the promised results, and the civil rights movement, rooted in the church and the South, seemed short of answers to the problems of black people living in the cities of the North and West. For many, the assassination of Martin Luther King Jr. settled the case that marches and nonviolence were no longer enough.

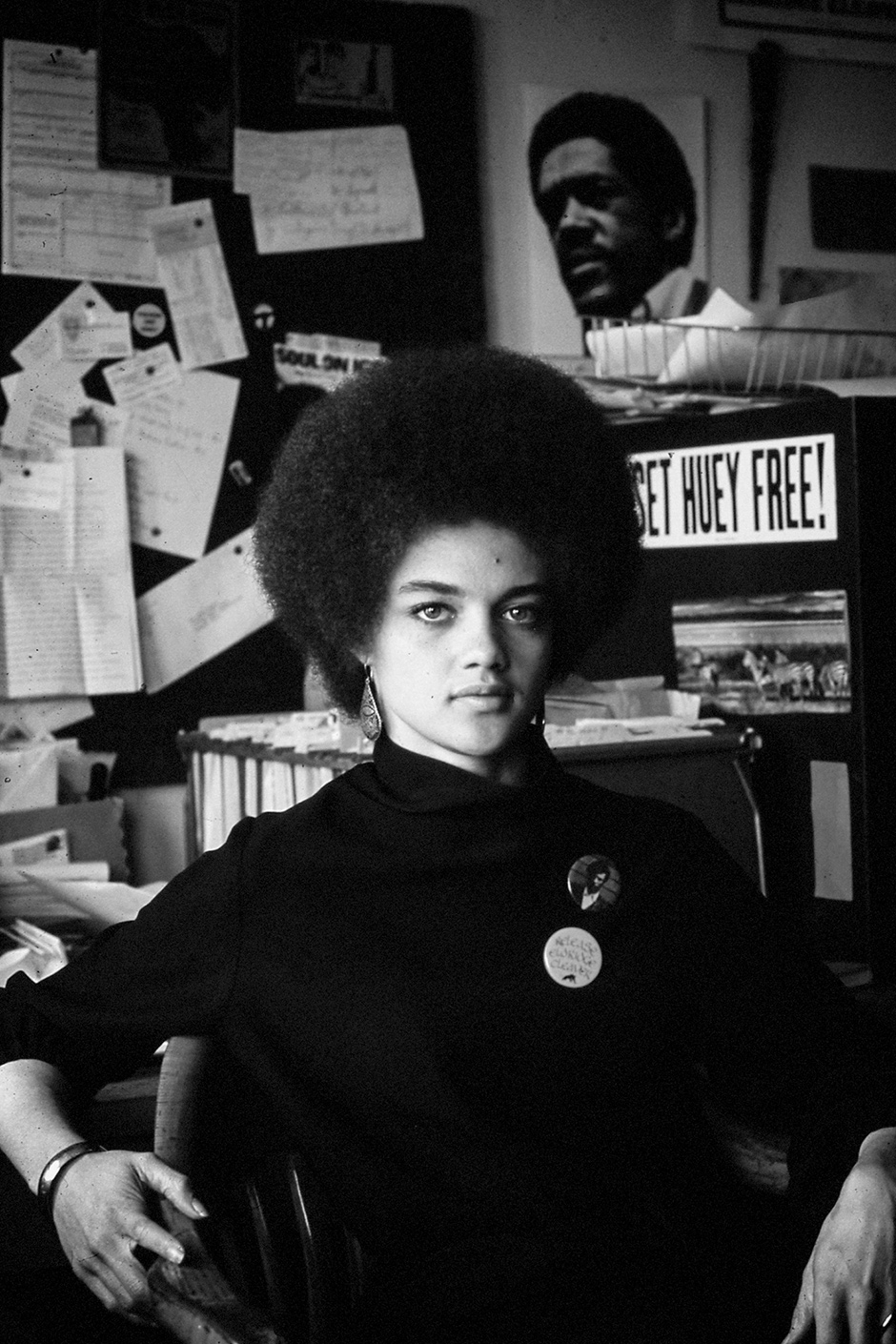

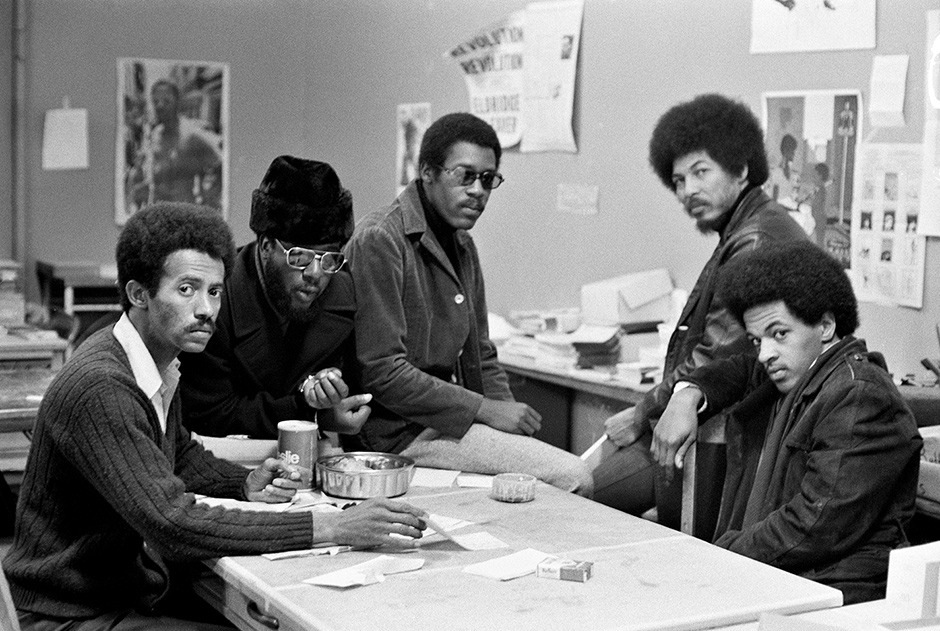

Stanley Nelson’s excellent documentary The Black Panthers: Vanguard of the Revolution is one of a number of recent works that take us back to these times and deliberations. The Black Panther Party for Self-Defense began as a neighborhood watch of armed young men monitoring encounters between the police and African- Americans in Oakland, California. They would “maintain a legal distance” and “observe these so-called law officers in the performance of their duties,” one of the original Panthers recalls in the film. They wore leather jackets and berets and cast a wide spell. “If you were a young man living in the city anywhere,” the late Julian Bond tells us, “you wanted to be like this, you wanted to look like this, you wanted to act like this, you wanted to talk like this.”

The armed patrols were short-lived, lasting only as long as a California law allowing unconcealed weapons to be carried in public. (As soon as the Panthers took advantage of that statute, Republicans and Democrats came together to repeal it.) By 1968 and 1969, when the Panthers went national and their ranks swelled, they were downplaying talk of guns or violence and seeking to become known more as community organizers and providers of social services, including medical clinics, a shuttle bus operation for relatives of prison inmates, and free breakfasts for schoolchildren.

This is, by the filmmaker’s choice, a bottom-up view of the party. We learn next to nothing about the early lives of its cofounders, Huey Newton and Bobby Seale, and Nelson glides lightly over such matters as how the many Panther programs were financed, other than through the sale of the party newspaper—the explanation offered by one former Panther. The film’s great achievement is to capture the enthusiasm and energy of the men and women (about half and half eventually) who formed the rank-and-file. “We knew the party we were in, and not the whole thing,” says Ericka Huggins, who joined early and wound up serving as director of a Panther elementary and preschool in Oakland.

One thing that united all Panthers, though, was their commitment to the cause that, during Newton’s three years in prison on charges of killing an Oakland police officer, got reduced to the words “Free Huey”—words “spray-painted on countless walls and fences,” we hear the anchorman David Brinkley noting at the time. Newton, the film makes clear, served the party best when he was behind bars and had to leave the leading to others. One of the basic tenets of his political creed was a faith in the revolutionary utility of criminals and thugs, or what Karl Marx (more skeptically) called the lumpenproletariat. From joyous scenes of Newton’s release in August 1970, the documentary moves quickly to recollections of him installed in a penthouse apartment, surrounded by ex-inmate enforcers, presiding over an effort to organize the Oakland underworld and directing the beating and purging of people who had annoyed or crossed him. “We had created a cult of personality around a fucking maniac,” one former Panther laments.

Nelson’s film, having made the important point that leaders cannot define an organization, goes on to confirm the sad truth that they often have the power to destroy one. In the Panthers’ case, the destruction was wrought jointly by Newton and Eldridge Cleaver, their information minister and chief marketer, who had fled to Cuba and then Algeria to escape a charge of attempted murder. As the head of a new “international section” of the party, Cleaver denounced the leaders back home for going soft and neglecting their duty to fight nonstop for the overthrow of the United States government.

Advertisement

In much of the bad fortune that befell the Panthers, the hand of the FBI and Director J. Edgar Hoover was also powerfully evident. Hoover had publicly described the Panthers as “the greatest threat to internal security of the country,” and the bureau used its full bag of dirty tricks to, in the words of one of several FBI memos that get well-deserved close-ups, “expose, disrupt, misdirect, discredit, or otherwise neutralize” their activities. In December 1969, Chicago police, equipped with a floor plan supplied by an FBI informant, killed two Panthers, Fred Hampton and Mark Clark, in a predawn attack on a communal apartment. Although the police claimed to have been responding to a barrage of gunfire from inside, a federal investigation tallied between eighty-two and ninety-nine shots fired by police, and just one by a Panther. It was a “shoot-in” rather than a shootout, a black Chicago police officer said at the time.

Hampton, who envisioned a “Rainbow Coalition” long before Jesse Jackson picked up the term, was a talented organizer and mesmerizing speaker who had vaulted to a leadership position in the Illinois chapter of the party while making alliances with organizations of working-class whites and Latinos. He embodied the hopes of some Panthers for a leader who could transform the party into a national movement with a long-term strategy. One of the many obsessions of FBI Director Hoover at this late stage of his rule, though, was a premonition about the rise of a charismatic black messiah, something he was determined to prevent. However much or little this concern may have figured in Hampton’s death, the Chicago assault was part of a campaign of police raids, arrests, and drawn-out court cases that had a devastating effect, driving many Panthers from the party.

An ugly epilogue falls outside the scope of Nelson’s film but squarely within the sights of Bryan Burrough’s new book Days of Rage: bands of former Panthers, mostly from the New York City chapter (which had been wrecked by the arrest and trial of a group known as the Panther 21), took up Cleaver’s call to go underground and operate as urban guerrillas under the “Black Liberation Army” banner. It was a decentralized operation. Cleaver preferred to communicate with the troops through occasional audio recordings, known as “voodoo tapes”; carried across the Atlantic by courier, they were more theoretical than practical. But the BLA was organized enough at one point to begin setting up a training and recruiting center in Atlanta, where teenaged aspirants were sent out into the streets to kill police officers, randomly, as an initiation rite. The first pair of recruits handed this assignment succeeded, says Burrough, murdering an Atlanta officer named James Greene in November 1971. Before a second pair could find a victim, they got arrested on firearms charges, forcing the Atlanta group to disperse; some of them later got into a shootout with police in North Carolina, where four more BLA soldiers were arrested and a sheriff’s deputy shot and paralyzed. Over a nine-month span BLA groups were responsible, Burrough estimates, for seven police assassinations and roughly ten failed attempts in New York, Georgia, North Carolina, and California.

Burrough’s aim is to give a comprehensive account of the various bands of self-proclaimed revolutionaries who came and went between the late 1960s and the early 1980s. It proves to be a difficult task. In his effort to fit them all into one big group portrait and stir fresh interest in (as the subtitle has it) a “forgotten age of revolutionary violence,” Burrough often employs a heavy brush. “After years of talk and restlessness 1968 changed everything,” he tells us in a chapter about the student radicals who would go on to become the Weather Underground. “Suddenly there was a single word on everyone’s lips: ‘revolution.’” A lot of things happen “suddenly” or “overnight” in this feverishly written book; but it is, at the same time, a prodigious feat of reporting, and it brings out some of the common reasons why none of these groups lasted long or achieved anything that even their proudest survivors can credibly cite as justification for the harm they did to others or themselves.

One of the survivors tracked down and interviewed by Burrough is Sekou Odinga, who spent time at Cleaver’s side in Algeria before returning to the US in a disastrous effort to revive the BLA in the mid-1970s, leading to a twenty-five-year prison sentence, which he served in full. “One of the things we now know, and should’ve known then, is we were way out in front of the people,” Odinga said after his release in 2014. “A little more study would’ve made that clear.”

Advertisement

“Revolution in America?” Not likely, was the conclusion of the political sociologist Barrington Moore Jr., in an essay of that title published in these pages in January 1969. Those who believed otherwise were extrapolating from the successes of guerrilla movements in China, Vietnam, and Cuba—peasant countries characterized by weak central governments and, Moore wrote, a “loss of unified control over the instruments of violence: the army and the police.” Urban revolutions in general had a poor track record, he added, because city dwellers of all classes tend to have ties of dependency to the state and the mainstream economy. Urban America, moreover, was experiencing a surge of violent crime. For many inner-city blacks (the BLA’s logical base), young men who attacked police officers and committed holdups to raise money for their supposed revolution were part of the problem, not the solution.

In April 1970, President Nixon announced that he had sent troops into Cambodia, where the US had months earlier begun a bombing campaign, originally secret but since exposed. The PBS documentary The Day the ’60s Died: The Kent State Shootings includes footage of a unit of scared and unhappy US soldiers in Cambodia, with a voice-over of one, Sergeant Terry Braun, recalling the crackly radio broadcast from which they learned that four protesting students at Kent State University had been killed by the Ohio National Guard. “We were all in shock,” Braun says. “The National Guardsmen would have been about our age. The students at Kent State would have been about our age, too.”

This is a remarkable film, with its parallel portraits of two sets of young Americans misused by the country’s leaders—those required to fight and possibly die in a horrific and unjust war, and those vilified and punished (and in a few cases killed) for publicly objecting. The Nixon administration had a deeply cynical strategy for dealing with the antiwar movement (to which it was, privately, anything but indifferent). One part of the plan, even as the US rained more destruction on far-off enemies and civilians, was to assuage domestic opposition by ending the draft and promising a negotiated peace. Another part was to stoke middle- and working-class anger against what Nixon, in a press conference after Kent State, called “these bums, you know, blowing up the campuses,” in contrast to “kids who are just doing their duty…and they stand tall.” The effectiveness of the strategy was validated, the film notes, by a Gallup poll in which 58 percent of the respondents held the unarmed Kent State students responsible for their own deaths.

Two months earlier, the Weather Underground had gained national attention by accidentally destroying a townhouse in Greenwich Village, killing two members of a Weather team preparing (Burrough persuasively argues) to set off their explosives at a military officers’ dance at Fort Dix, New Jersey. A few weeks after Nixon spoke, the group’s unofficial leader, Bernardine Dohrn, issued a public declaration of war on behalf of “people fighting Amerikan imperialism,” who, she said, “look to Amerika’s youth to use our strategic position behind enemy lines to join forces in the destruction of the empire.”

Insofar as the Weatherpeople had a base of popular support in mind, it was the counterculture. “If you want to find us,” their declaration of war stated, “this is where we are: In every tribe, commune, dormitory, farmhouse, barracks and townhouse where kids are making love, smoking dope and loading guns.” Later that year, they would engineer the prison escape of the LSD avatar Timothy Leary, who, it was explained, had been held captive “against the will of millions of kids,” for “helping all of us begin the task of creating a new culture on the barren wasteland that has been imposed on this country by Democrats, Republicans, capitalists and creeps.” This kind of outreach, while failing to attract a notable following of freaks or hippies, helped turn the Weather Underground into the perfect lightning rods for Nixon’s “silent majority.”

Unlike the other groups Burrough writes about, Weather had above-ground benefactors (mainly “a group of radical attorneys in Chicago, New York, San Francisco, and Los Angeles,” he says), relieving them of the need to carry out robberies to fund themselves. After the townhouse bombing, they resolved to avoid acts that would cause physical harm; instead, Burrough writes, “they would bomb buildings of symbolic importance—courthouses, military bases, police stations—but only after warnings, and only at times when the buildings were likely to be empty.” As a result, quite a few of them were ultimately able to resurface and resume the lives of comparative privilege they had seemingly left behind. In revolution as in other things, we are reminded, this is a country where it really helps to be white.

The townhouse episode makes for rather a large asterisk, however, in the claim made by Dohrn’s husband Bill Ayers during a 2008 TV interview that the Weatherpeople could not rightly be called terrorists because “we never killed or hurt a person—we never intended to.” In any case, they did not advertise their restraint at the time, and in their communiqués as well as their actions seemed almost to welcome working- and middle-class contempt.1

Mark Rudd, the onetime leader of the Columbia University chapter of Students for a Democratic Society, spent seven years in the Weather Underground before bailing out in 1977. “Much of what the Weathermen did had the opposite effect of what we intended,” he wrote in a 2009 memoir on which Burrough draws.

We deorganized SDS while we claimed we were making it stronger; we isolated ourselves from our friends and allies as we helped split the larger antiwar movement around the issue of violence. In general, we played into the hands of the FBI—our sworn enemies. We might as well have been on their payroll.

Some of the groups and most of the particulars that Burrough writes about are little-known. But his big picture—of the late 1960s and 1970s as a time when the New Left and the Black Power movements went off the rails—is all too familiar. Those on the lookout for an undertold story of the period would do better to consult Martha Biondi’s The Black Revolution on Campus. “The Black liberation movement did not unravel after the murder of Martin Luther King Jr.,” she writes, “but grew and irrevocably changed the landscape of American higher education.”

Black students played a disproportionately large role, she notes, in protests at a number of schools, including Northwestern, Ohio State, Cornell, and San Francisco State, where, comprising just nine hundred members of a student body of 18,000, they were the pivotal force in the strike of November 1968, persuading many white classmates to support their call for, among other things, open admission for all of the state’s black high school graduates. The same wave of activism swept through many of the historically black colleges and universities, or HBCUs, where more than half the nation’s black students (some 75,000 out of 150,000) were enrolled as late as 1968.

In early February 1968, police opened fire on a group of South Carolina State University students protesting the continued segregation of a bowling alley and other public facilities, four years after passage of the Civil Rights Act. Three students were killed and nearly thirty wounded in what became known as the Orangeburg Massacre, which inspired sympathy protests—and more faceoffs with authorities—at North Carolina A&T, Howard (in Washington, D.C.), Fisk (in Tennessee), Morgan State (in Maryland), Cheyney State (in Pennsylvania), Tougaloo (in Mississippi), and the Tuskeegee Institute (in Alabama).

At a time when the HBCUs were widely seen as anachronisms and their leaders were waging a defensive effort merely to justify their survival, militant students and their faculty allies wanted to make something more of these institutions. Their blueprint was a 1967 speech in which the political scientist Charles Hamilton advanced the idea of a “black university” that would “deliberately strive to inculcate a sense of racial pride and anger and concern in its students.” The creation of Black Studies programs or departments was a common goal of protest campaigns at the HBCUs and predominantly white schools alike. Biondi frames that much-debated quest as part of a larger effort by politicized black students and faculty members to create space for mutual support, widen the pathway of advancement for others, and use their own opportunities and knowledge, along with the economic and intellectual resources of their institutions, to “help solve problems in poor Black communities.”

Their activism spurred a powerful conservative backlash, but nevertheless had profound long-term effects, Biondi says, on admissions and hiring practices, black attendance and graduation rates, campus–community engagement, and scholarship. “While the white student movement of the late 1960s has garnered much more attention,” she argues, “Black student protest produced greater campus change.”

The 1970s and 1980s are often described as a time when activists retreated from politics in order to pursue their own personal and professional advancement. Some of the subjects of Biondi’s book followed that path; some of the faculty activists, she adds, suffered professional reprisals that permanently damaged their careers. “But for many, many others,” she writes, “those tumultuous college years were the beginning of a lifetime of activism, public service, or political and legal advocacy.”

A similar sense of continuity is conveyed by the opening scenes of Johanna Hamilton’s documentary 1971, which introduce us to a group of Philadelphians, mostly young adults working at a variety of white- and blue-collar day jobs, who plan nighttime raids on draft boards in order to cause “as much damage to the war machine…as we could before we got caught,” as one of them, Bonnie Raines, explains in the film. (It is based on Betty Medsger’s book The Burglary.2) At the end of 1970, they accepted a more dangerous assignment: breaking into an FBI office in hopes of documenting illegal surveillance and other misdeeds directed against antiwar activists.

William Davidon, the Haverford professor of physics who proposed the idea, was out to protect the First Amendment, but also to temper the rage of dissenters who might be leaning toward violence. That motive was very much in the mind of Reverend Daniel Berrigan, the Jesuit priest who had pioneered the practice of stealing and destroying draft records. After the townhouse bombing, Berrigan issued an open letter to the Weather Underground commending a “new kind of anger which is both useful in communicating and imaginative and slow-burning, to fuel the long haul of our lives.”

Davidon had concluded that a big-city FBI office would have too much security. He chose the small regional office in the town of Media, Pennsylvania, which was improbably located on the second floor of an apartment building and had an ordinary five-cylinder lock on the door—easily beaten by their designated breaker-in, Keith Forsyth, who made his living as a part-time cabdriver and had prepared for the mission by taking a correspondence course in locksmithing. The Citizens Commission to Investigate the FBI, as they designated themselves, came away with 50,000 pages of material, and with findings (including the first public evidence of COINTELPRO and its “blackbag” operations) that far exceeded their vague hopes.

Although the documents they stole included abundant proof of illegal activities directed at the antiwar movement, it turned out that the bureau viewed the Panthers and other Black Power groups as a much more serious enemy. “I cannot overemphasize the importance of expeditious, thorough, and discreet handling of these cases,” Hoover wrote in a memo about the need to monitor black student groups even if they had never been involved in a disturbance. That priority probably explains a 1970 directive authorizing agents to recruit and pay informants as young as eighteen, rather than twenty-one, the previous cut-off age.

The Media burglary led by a direct if far from swift path to the Church Committee hearings of 1975, and then to the first modest legal limits on FBI activities. Perhaps just as important, Davidon and his colleagues had set off a wave of disclosures that took the FBI down a healthy several notches from the place of national worship it had occupied. By 1976, the Justice Department had launched multiple investigations of FBI crimes.

One result, according to Burrough, was consternation in what was known as Squad 47, a unit largely devoted to the pursuit of the Weather Underground. “The men of Squad 47 panicked,” he writes, “furiously disposing of thousands of pages of Weather- related internal documents.” A combination of tainted and missing evidence forced the government to abandon many cases. One of the beneficiaries was Bernardine Dohrn, who had made the FBI’s Ten Most Wanted list in the early 1970s. By December 1980, when she and Ayers surrendered in Chicago, it had become apparent, says Burrough, that “no one was looking for them anymore.”

The Media burglars escaped their own FBI dragnet. In fact, they kept their crime to themselves for forty years, until most of them agreed to go public in Medsger’s book. It was only through that exercise that they came to understand how much they had done to reverse the police-state tide of the Nixon years.

The documentary, like the book, identifies their break-in as the first in a line of conscience-driven disclosures of government offenses against privacy and the rights of speech, association, and dissent, continuing on up to the NSA leaks of Edward Snowden. The Media burglars also compel our interest because they wrestled hard with a broader, and equally persistent, question: how to work for deep and necessary change when the obvious forms of advocacy, to say nothing of the workings of our corrupted democracy, seem unavailing. Their efforts, like those described by Biondi, remind us that alongside the cautionary tales, recent history holds examples of Americans who have joined forces to take action that was thoughtful, brave, sometimes confrontational, occasionally illegal, and ultimately fruitful, leaving us with a better country and more grounds for hope.

This Issue

September 24, 2015

Urge

Hitler’s World

Trump

-

1

Two of the founding members of the Weather Underground, David Gilbert and Kathy Boudin—she had fled from the townhouse explosions—became attached to a BLA spinoff group known as the Family. In October 1981, they participated in the robbery of a Brinks truck in Rockland County, New York, which led to the killings of two police officers and a security guard. Boudin spent twenty years in prison. Gilbert is still incarcerated. ↩

-

2

The Burglary: The Discovery of J. Edgar Hoover’s Secret FBI (Knopf, 2014); reviewed in these pages by Aryeh Neier, October 23, 2014. ↩