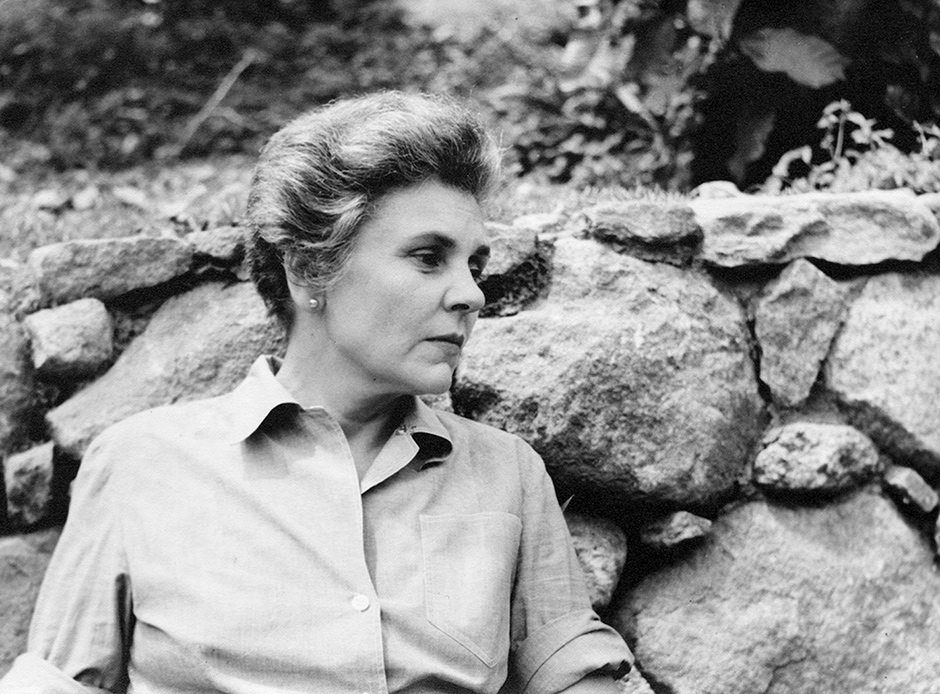

On Elizabeth Bishop is the Irish writer Colm Tóibín’s exquisite study of the American poet, a book whose modest proportions suggest the personal nature of the connection. Tóibín has written a book he could have carried along with him in the nomadic period this study recalls, when, far from home, Bishop’s poems of travel and memory, also deceptively slight, first made their impression on him.

Bishop is a “writer’s writer’s writer,” according to John Ashbery; she tends to mean everything to writers to whom she means anything. Her work provided for Tóibín what Kenneth Burke said literature can provide: “equipment for living” under conditions (the early loss of parents, the awakening to one’s homosexuality, the discovery of a vocation for writing) that recalled Bishop’s own. The tact and poise and proportion Tóibín learned from Bishop are the very qualities that make this study of the poet so satisfying.

The book is partly a defense of understatement. Bishop’s Nova Scotia, where she spent the happiest years of her childhood, and Tóibín’s southeastern Ireland, both, according to Tóibín, value language partly as “a way to restrain experience, to take it down to a level where it might stay.” The implication is that “experience” is too wayward and threatening to be left alone, and that language is less a working out than a tamping down. This is the tension we find in much of Bishop’s work, where a style pared of ornament and excess implies—and, with growing openness across the arc of her career, explores—the painful life material it paradoxically “restrains.” Frost’s idea of poetry as a “momentary stay against confusion” comes to mind; Frost, whose influence on Bishop has rarely been noted, is yet another writer whose region and family predisposed him to defend in his poems the virtues of reticence and skepticism manifested by his poems.

It is also a study of shyness, which, whatever its root, is a trait so many writers possess. For a writer, speaking is terrifying, since it operates under conditions foreign to composition: one might be interrupted or distracted, or find one’s meanings questioned before they are fully developed and expressed. Tone, which is entirely in the writer’s hands, seeps into speech from circumstances no writer can control: his accent, his reflexive vocabulary, the pitch of his voice, even his appearance and posture—these are all elements of spoken self-presentation that cannot really be controlled in the moment, in social interaction. Advantage: writing. But writing may lack the lifeblood, the qualities of surprise and innovation, we find in speech. How can a writer recreate speech on the page, not excluding the thrill of risk and innovation we find in the most brilliant conversation?

Bishop’s poetry, with its ingeniously crafted personae and deflections of a thousand kinds, makes a preemptive strike against embarrassment. Tóibín, who developed a stammer around the time he was eight, after his father’s brain surgery had made it so that his son “could not understand him when he spoke,” turns to writing as a way of ruling out all the anticipated shame of speaking. “I have a close relationship with silence, with things withheld, things known and not said,” he writes.

I am sure that no one said anything to me, for example, before I went into that room where I saw my father after the operation. And no one mentioned afterward that we would not easily be able to understand his speech, and that my speech was also a problem. What was there to say? And we lived like that for three and a half years; we got used to it. And then in July 1967 my father died. There was a funeral and the house was full of people, but there was silence again soon afterward.

The silence is collaborative and cumulative; if you grow up in these circumstances, you attach naturally to objects, since they too seem to be standing in the midst of pain with a kind of ceremony and integrity. A passage from Bishop’s late masterpiece “Crusoe in England” comes to mind:

The knife there on the shelf—

it reeked of meaning, like a crucifix.

It lived. How many years did I

beg it, implore it, not to break?

I knew each nick and scratch by heart,

the bluish blade, the broken tip,

the lines of wood-grain on the handle…

Now it won’t look at me at all.

The living soul has dribbled away.

My eyes rest on it and pass on.

There are many such objects in Bishop—an ashtray, a stack of envelopes, the “Large Bad Picture” described in the poem by that name—whose “living soul” can be restored only by the attention she pays to them in language, in retrospect. The question of silence in Bishop’s work immediately points us to these extraordinary objects that seem somehow to have been stunned into mute passivity.

Advertisement

Reading Bishop with Tóibín as our guide, we encounter a poet whose early losses underlie her surfeit of description, as though the world, painstakingly mapped, could compensate for the deracinations of the child. Her biography is well known: she was born in 1911; her father died when she was eight months old, while her mother, suffering under the strains of grief, went mad and was institutionalized in 1916. Though she lived until 1934, Bishop never saw her again. Bishop, knowing that her mother was alive, was then passed from relative to relative before being sent to boarding school, at Walnut Hill School, in Natick, Massachusetts, and then to Vassar. Her childhood and early adulthood, including her formative years as a poet, were all conducted in light of Bishop’s knowledge that her mother was very much alive. What a strange predicament, to have closed the books on a childhood that was by no means safely in the past. Loss is always mingled with guilt; in this case, the two were causally connected.

Such a difficult early life might have kindled in some writers a desire to put down roots and stay put. But a change in outward circumstances can tend to solidify the continuities within, and Bishop’s poetry, from the beginning, expressed the peculiar phenomenon of feeling always like oneself, never more, never less, whatever the accidents of time and place. The farther one goes in time and distance from one’s childhood, the more surprising it is to find the self essentially unchanged; that irony, deepening with time, is Bishop’s real subject, and it meant that she would almost necessarily have a great late period. Indeed her last book, Geography III, is her best and her most poignant.

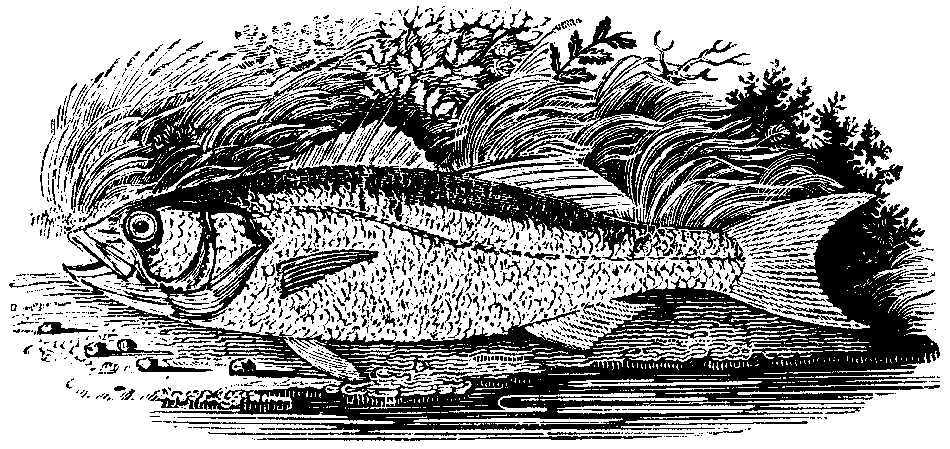

Bishop is still sometimes misunderstood as a poet of elegant description, visually exact if psychologically remote. Lost were the moral dimensions of description, which become clear every time a poet chooses to describe one thing instead of another—this sandpiper, this doily, this armadillo—for a specific duration and in a deliberate sequence. Her canniest illustration of these choices and their associated risks is “The Fish,” which for years was Bishop’s best-known poem. (It has been supplanted by “One Art,” her brilliant villanelle: a better but less interesting work.) The poem was in some anthology I encountered as a teenager, predictably offered as a lesson in precision and detail. The poem traces the arc of a single action, catching and releasing a fish: its first line is “I caught a tremendous fish”; its last line, concluding a complex twelve-line sentence, is “And I let the fish go.” In between, we get description: exquisite, “apt,” almost an MFA workshop lesson avant la lettre in the crafting of vivid detail:

He was speckled with barnacles,

fine rosettes of lime,

and infested

with tiny white sea-lice,

and underneath two or three

rags of green weed hung down.

While his gills were breathing in

the terrible oxygen

—the frightening gills,

fresh and crisp with blood,

that can cut so badly—

I thought of the coarse white flesh

packed in like feathers,

the big bones and the little bones,

the dramatic reds and blacks

of his shiny entrails,

and the pink swim-bladder

like a big peony.

The poem is so explicit about its cruelty as to be almost a kind of prank, and yet critics have usually missed the point: description takes time, time the fish, “breathing in/the terrible oxygen,” can’t spare. “The Fish” is Bishop’s take on poetry’s claim to timelessness, which leaves out the fact that timeless things are encountered in time. Substitute for the expiring fish Bishop’s own mortality, and ours, and we see how cunning a poet of temporal emergency Bishop in fact is. Just because we die more slowly than an asphyxiating fish doesn’t make the passing moments any less serious, as the remaining years become hours become days and moments.

One of the ways Bishop indicates the tragic content she will not disclose is to commit her speakers to blinkered, near-comic excesses of description. She differs from her great mentor Marianne Moore in that, for Bishop, “relentless accuracy” is not so much a goal as a dodge, since it so often operates on the surface of very deep waters. It is better to have emotions than to have descriptions.

“The Armadillo” charts the arc of celebratory “fire balloons” on a warm night in Brazil. They begin, as Tóibín puts it, “merely pretty,” before quickly turning “lethal”:

Advertisement

This is the time of year

when almost every night

the frail, illegal fire balloons appear.

Climbing the mountain height,

rising toward a saint

still honored in these parts,

the paper chambers flush and fill with light

that comes and goes, like hearts.

So far so good; and yet that word “frail,” since it is usually reserved for the ill or the elderly, suggests a level of threat hidden to the speaker, who insists on cosmetic touches like the rhyme of “parts” with “hearts.” In fact these “fire balloons”—the very name suggests ruined innocence—will soon plummet from the sky and ignite the landscape, a catastrophe that the speaker seems morally incapable of noticing:

Last night another big one fell.

It splattered like an egg of fire

against the cliff behind the house.

The flame ran down. We saw the pairof owls who nest there flying up

and up, their whirling black-and-white

stained bright pink underneath, until

they shrieked up out of sight.The ancient owls’ nest must have burned.

Hastily, all alone,

a glistening armadillo left the scene,

rose-flecked, head down, tail down,and then a baby rabbit jumped out,

short-eared, to our surprise.

So soft!—a handful of intangible ash

with fixed, ignited eyes.

The word “another” requires us to go back to the start of the poem and register its leisurely, aestheticizing description as a form of willed blindness; what has just happened had happened already. But this speaker is chronically deficient in the kinds of sympathy that Bishop possesses in spades; often her poems are spoken by figures whose illusion of command, sustained despite worsening crises, distinguish them from Bishop, who knows not to strike the naturalist’s note (“short-eared, to our surprise”) when a rabbit is on fire.

Bishop’s poems often send us back to their beginnings, the second time through highly colored by revelations at their close. “The Fish” is a different poem once we’ve read it, as is “The Armadillo,” as is “The Moose,” her magnificent narrative poem about a bus trip from Nova Scotia to Boston. This is also the pattern in her career, the late poems revisiting images and details from the early ones, the sense of an origin changed by having already arrived at our destination.

Tóibín’s little book on Bishop is a writer’s exercise in rechristening himself, a second time through with Bishop as his chaperone. The narrative draws us back to moments when the discovery of Bishop, and later of Thom Gunn, drew Tóibín forward. This is the kind of beautiful relay that great writers provide for each other, and it gives you hope that some young person somewhere who finds himself in a bind will pick this short book up and find in it not one, but two companions.

This Issue

September 24, 2015

Urge

Hitler’s World

Trump