1.

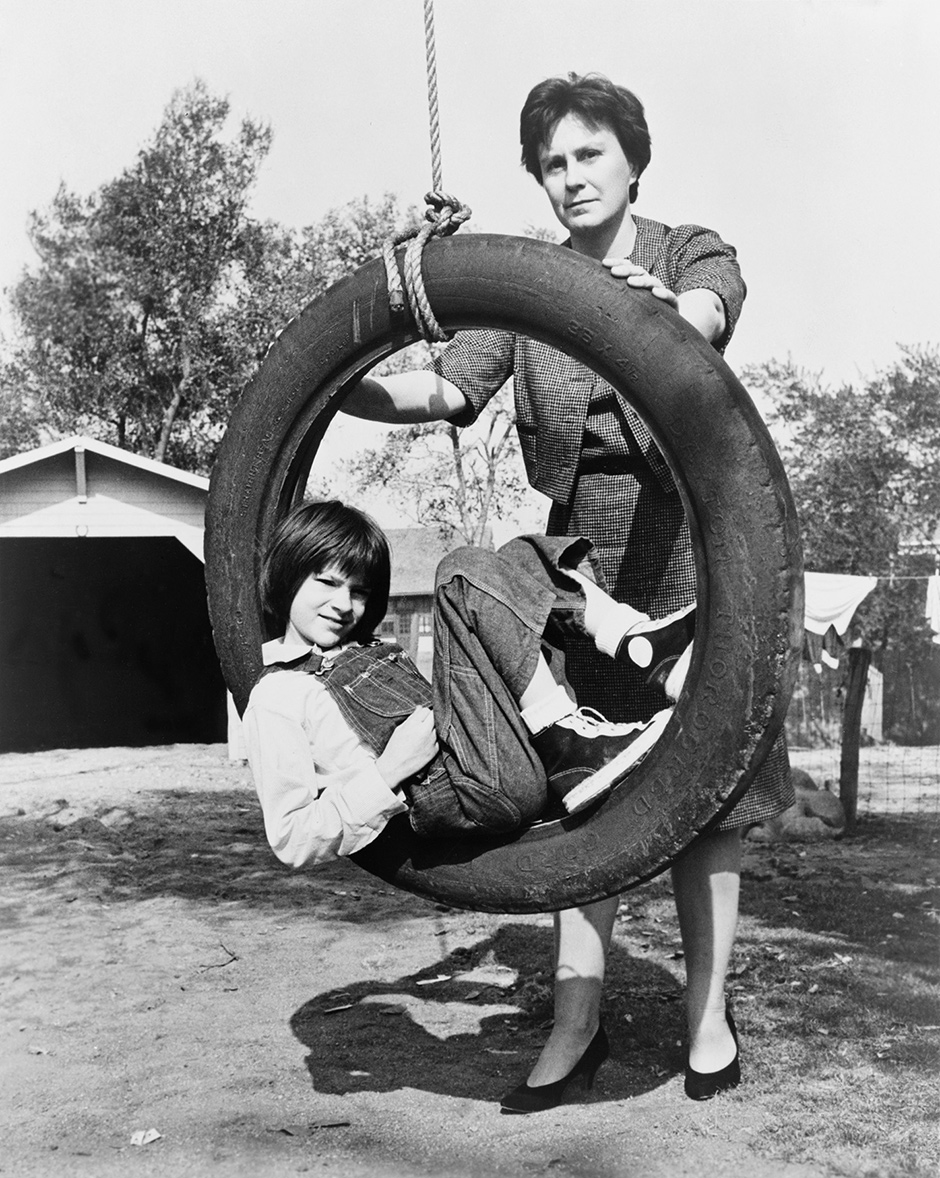

Since its publication in 1960, Harper Lee’s best-selling To Kill a Mockingbird has been described as America’s favorite book. It is required reading in many high schools and junior high schools and in schools in some foreign countries, and continues to sell more than a million copies a year. In it, a charming, combative child, Scout Finch, growing up safe and unconstrained in the small, old-fashioned, southern town of Maycomb, Alabama, glimpses some ugly realities of black–white relations and worships the exemplary behavior of her father, Atticus Finch, as he defends a black man falsely accused of rape and eloquently articulates many of our highest principles. For American readers, Atticus Finch has become an icon of lawyerly integrity, and the book itself an eloquent plea for racial harmony and civil rights.

After the huge success of To Kill a Mockingbird, the author withdrew to spend more and more time in her real-life small southern town of Monroeville, Alabama, and to general dismay, announced that she had “said what I wanted to say and will never say it again.” She published nothing further, so when after more than fifty years a new novel was announced, the joy, excitement, and calculation may be imagined; it was as if someone had found a sequel to Gone With the Wind. Pre-publication of the great discovery was surrounded by hush-hush embargoes and restrictions, and suspense mounted about what new literary pleasures and surprises this very much desired sequel would bring. Go Set a Watchman was a huge best seller even before its release.

The first reactions were of wary disappointment, charitable attempts to praise the many good qualities of the new novel, and, almost immediately, close rereadings of To Kill a Mockingbird, to see how the two works fit together. Above all, people wondered why Watchman was so much less accomplished than Mockingbird. A host of extraliterary issues immediately began to shadow its reception: first, the circumstances of its discovery, which raise questions of provenance and ownership; second, the work of its editors, both here and in the case of Lee’s earlier novel, the now classic Mockingbird; third, the implications of Lee’s possible mental and physical impairments for any critical approach to the work (are late de Koonings worth as much as those done before his Alzheimer’s?); fourth, the actual quality of the work itself; and finally, what was going to happen to the vast sums of money already mounting up?

Since suffering a stroke in 2007, the reclusive Harper Lee has been in an assisted living facility in Monroeville, watched over by her lawyer sister “Miss Alice” Lee until Alice’s death (aged 103) in 2014. A few days after Miss Alice died, the manuscript was “found” in “a secure location” by her present lawyer, Tonja Carter, Alice’s assistant. Carter took the felicitous discovery to the appropriate literary agent, and has since explained that

accidents of history sometimes place otherwise unknown people in historic spotlights. Such was my fate when last August curiosity got the best of me and I found a long-lost manuscript written by one of America’s most beloved authors.

Carter’s account, however, has been challenged on several points, especially about when she found the manuscript; according to some, it was the subject of a 2011 meeting between agents and an appraiser at which Carter was present, though she says she wasn’t there for all of it and never saw the manuscript back then. If she had been there, it suggests that she and others knew about the manuscript and were sitting on it until Miss Alice Lee died, perhaps because she would have objected to its publication. The granddaughter of the original editor, Tay Hohoff, has been quoted as saying that her grandmother would not have approved of Go Set a Watchman in its present form, that is, without detailed editorial work, though Harper Lee has been said by her publisher to want “the novel published exactly as it was written, without editorial intervention.” Does this explain the difference in literary quality and social point of view?

Compared to To Kill a Mockingbird, Go Set a Watchman is cursory, often clumsy, and seems to modify, even reverse, some of the attitudes and events of the first novel, raising questions about the part of editors in Mockingbird’s more accomplished writing and liberal tone. According to its editors and Harper Lee herself, To Kill a Mockingbird had profited from extensive editing at R.B. Lippincott by the late Tay Hohoff, who said that she and Lee worked for two years on the project. Lee’s representatives have explained that Go Set a Watchman is in fact the original manuscript from the 1950s, minus the parts that became Mockingbird—parts that focus on Scout’s childhood. Watchman is in effect cobbled together from the remainders that were too good to lose after Mockingbird was extracted and augmented with editorial help.

Advertisement

The “new” novel Go Set a Watchman uses material about Scout in her twenties, and develops the real subject of the original manuscript: disillusion with her father and the South. (About the editing, the English newspaper The Guardian, not constrained by our national sensitivities, remarks that in reading Go Set a Watchman, “it is hard not to feel some awe at the literary midwives who spotted, in the original conception, the greater literary sibling that existed in embryo.”)

Lee’s collaboration with the new publication is viewed with skepticism by longtime Monroeville residents, like the Methodist minister, who says:

Nelle Lee had a stroke, she doesn’t remember anything, she’s essentially blind, profoundly deaf and confined to a wheelchair…. You can draw your own conclusions. They’d probably be the same as mine…. I’ve known Miss Nelle since the 1980s and her sister since 1965 and no suggestion of another book had come to light before. It makes you wonder.

“My reaction?” says restaurant owner Sam Therrell, “disgust and disdain. I don’t think that Nelle or Alice had any idea that it had even been written. I’ve no idea why people are being kept away from seeing Nelle.”

Lee’s London literary agent said that she was “feisty” when he saw her. She could no doubt resolve questions about her condition herself, but few are allowed by Carter to see her. Apparently alerted by a local doctor who had heard she was unresponsive after the death of Miss Alice in November 2014, the state of Alabama actually investigated her circumstances for “elder abuse,” though no abuses were found.

Meantime in Poland, textual scholars with sophisticated computer algorithms had already gone to work on both Mockingbird and Watchman to check out rumors that Harper Lee’s close childhood friend Truman Capote had written parts of Lee’s novels. Their answer? Basically he hadn’t; or maybe a little in parts; or else he had influenced her strongly at the end of Mockingbird; while Go Set a Watchman is all written by Lee. But any investigation is an implied challenge to the text and to Lee’s authorship, since most literary works are not subjected to such analysis.

Given concerns about Lee’s health and her intentions for this manuscript, the Polish data-mining prompts larger questions of authorship and authenticity. Did and does Harper Lee really want this manuscript to be published? Does its inferior quality somehow diminish her earlier accomplishment—questions asked of many posthumous publications, for instance certain Hemingway manuscripts? Is this a shameless exploitation for profit at the expense of her reputation, “one of the epic money grabs in the modern history of American publishing,” as The New York Times has it? And have we correctly understood the social attitudes expressed in Mockingbird?

2.

It’s easy to see in Go Set a Watchman the lineaments of the original work from which To Kill a Mockingbird was extracted. There is a classic frame, the prodigal daughter coming back to her hometown. Scout, now twenty-six and known by her grown-up name Jean Louise, comes home to Maycomb, Alabama, to visit her family after a few years in New York, as Harper Lee herself returned to Monroeville, Alabama. Scout’s brother, Jem, has died (like Harper Lee’s brother), and her beloved father Atticus is aging. All the events of small-town life unfold in a mostly normal fashion; she has a loyal suitor, there are relatives, and pranks, and friends who try to straighten out her life—but something has happened in Maycomb that she doesn’t understand.

Above all, she doesn’t understand the atmosphere of tension and stress, the harsh rhetoric, the new talk of “niggers,” and “them.” The historical setting is important: it’s 1957. Since she was last home, the Supreme Court has outlawed school segregation, and the NAACP—one of the villains of the piece—has been stirring up the area, with the result that local attitudes, formerly ones of cordial coexistence, have hardened into frank racism among whites, and hostility from blacks.

She finds that even her own family members—her Aunt Alexandra, her uncle, and her admired father—as well as her boyfriend Hank now talk in ways she couldn’t have imagined when she went off to New York a few years earlier. She’s shocked that her father would tolerate the kind of ugly racist diatribe she hears from one of his associates at the Maycomb County Citizens’ Council, a body that hadn’t existed before.

The reader, used to more conventional scenarios in which enlightened northern liberals confront redneck southern bigots, may take awhile to catch on that Jean Louise’s powerful reaction to her father’s demeanor is the real emotional center of the novel. It is not driven by activist indignation so much as by disappointment at his betrayal of what she had viewed as his own values, and by her nostalgia for the South of her childhood, that is, of the 1930s, when a mood of racial harmony and accommodation, as far as it appeared to her childhood self, governed the peaceful communities southerners often reminisce about, back when people were nice, “they” weren’t uppity, and everyone got along.

Advertisement

Watchman is set in the present of the 1950s; after Jean Louise arrives in Maycomb, the story flashes back to her childhood, the period covered in To Kill a Mockingbird. Several long sequences—for instance, Scout getting her first menstrual period, or believing she must be pregnant because a boy has kissed her, or being kind to an ostracized white-trash boy—could be easily slotted back into To Kill a Mockingbird unaltered.

We also get complete sketches of Uncle Jack, Aunt Alexandra, and other characters, which might be notes by a conscientious writer for the novel she was preparing to write. Between the flashbacks, the action returns to the present, where the newly arrived Jean Louise has encounters with each of these important people in her life in set pieces about the town; about Atticus, the boyfriend Hank, her cherished aunt; about their former cook, Calpurnia. But Jean Louise finds that Calpurnia has left their service; at the instigation of the NAACP, the formerly docile, friendly, and dependent local black folks have turned distant and hostile; the Supreme Court has taken away the right of the community to manage things in the way it believed had worked for a long time; attitudes have hardened; things are said that never were said before. All is uncertainty and anxiety. Jean Louise is distressed, even revolted, especially when she attends the meeting of the citizens’ council and realizes that one of the speakers, spouting vicious racist hate, is sitting with her father and Hank, who seem by their presence to condone it.

Lee has a fine disregard for certain conventions of storytelling, so we know nothing about Scout’s inner life except demonstrations of her childlike rage against the adults who disappoint her; disillusion becomes the emotional climax of the book. When she sees her father at the citizens’ council, she is literally sick: her reaction to his toleration of his racist friends is to throw up in the yard of an ice cream place (and to let the white-trash owner clean it up). Because a few pages earlier we had read about the scare she’d had at age eleven, fearing pregnancy when a boy put his tongue in her mouth, and because, despite the phrase “that makes me sick,” people rarely throw up when overhearing unpleasant things, in the overdetermined world of fiction our first thought is to wonder: Is Jean Louise pregnant? No, it’s Lee overdramatizing inner revulsion. If Jean Louise had coughed, we’d think she had tuberculosis.

Beside Jean Louise’s thoughts, there are other unexplored matters. Lee is not comfortable with the subject of sex. How does Jean Louise feel when Hank kisses her? We don’t know. She is a virginal twenty-six, shows no interest in marriage, and easily gives him up because of his unwise associations and lower-class origins. Her fate (like that of the Lee sisters) is of course to be that perennial small-town figure the old maid, the child who is sacrificed to be the caretaker of the parent. Go Set a Watchman alludes to this several times, as when Aunt Alexandra predicts that Jean Louise “would return and make her home with Atticus; that was what a daughter did, and she who did not was no daughter.” Uncle Jack seems to expect it too when he tries to warn her that her worship of her father is misplaced.

3.

For bookish Yankee children, at least, the worlds of the Old South and of Olde England were invented, distant, and exotic. English stories gave us castles and vassals; the South, plantations, hoopskirts, and slaves. Harper Lee gives us both. To emphasize the timeless or out-of-time qualities of their little community—Jean Louise’s Maycomb got its first paved street in 1936—she tells us that Anglophilia is a southern characteristic, and Uncle Jack maintains that the South is really an extension of England. Lee also tells us that the Finch family often reads from nineteenth-century Anglican theology, for instance Bishop Colenso, who believed that God created the races separately, or his defender Dean Stanley. But there are also echoes of what was actually in the news while Lee was writing the story: Atticus is keeping up with the Alger Hiss case, and criticizes an English author for daring to write a book defending Whittaker Chambers.

On my bookshelf growing up, I had Diddie, Dumps and Tot, or Plantation Child Life, by Louise Clarke Pyrnelle, an enormously popular children’s book, first published in 1886; my copy had belonged to my mother and possibly her mother. This book is so astonishingly un-PC that recently when I found an old copy, the bookstore owner, looking inside it, refused to sell it to me, shocked not by hate and violence but by the happy picture it painted of the white children and the slave “pickaninnies,” and how they loved each other. Pyrnelle was a native daughter of Selma, Alabama, and it seems highly likely that Nelle Harper Lee, eighty miles away in Monroe County, would have read this still widely known work when she was a child. In Lee’s Jean Louise and Scout—boisterous southern girls with a determination to be naughty in the face of their futures of conformity and femininity—there is much to remind of Diddie, Dumps and Tot. Scout, like Diddie, goes to the black church; Scout, like Diddie, befriends a poor black person; there’s a motherly black “mammy,” and so on.

As in many English and southern novels for young people, Lee’s writing tends to be formal, elaborate, multisyllabic in the manner of the nineteenth century, when many of the best-loved books were written. Go Set a Watchman has this nineteenth-century flavor. For example: “After nine hours of listening to the vagaries of Old Sarum’s inhabitants, Judge Taylor threw the case out of court on grounds of frivolous pleading and declared he hoped to God the litigants were satisfied by each having had his public say.” Or: “Jean Louise was accustomed to her uncle’s brand of intellectual shorthand: it was his custom to state one or two isolated facts, and a conclusion seemingly unsupported thereby.”

Whether or not they exist in life, certain characters are generally present in the southern novel. Calpurnia is both vivid and familiar from many other novels and films: we can all see Hattie McDaniel in the role, or Aunt Jemima on the pancake mix. In Diddie, Dumps and Tot, the Calpurnia figure is predictably called Mammy. (Faulkner has many—Callie, Dilsey, Elmora, Clytie, and more.) Other stock characters turn up, too: the shuffling blacks, the vicious white racist—the redneck Bob Ewell in To Kill a Mockingbird, Mr. Grady O’Hanlon in Go Set a Watchman; there’s usually a judicious white male authority figure, often with an honorific title like Colonel, Major, or Judge, here represented by both Atticus and Uncle Jack—Doctor Finch. The character of dumb southern belle is played by Jean Louise herself: “I don’t know much about government and economics and all that, and I don’t want to know much, but I do know that the Federal Government to me, one small citizen,” is bureaucracy, inefficiency, insensitivity, and meddling. Jean Louise believes in states’ rights and mistrusts all government institutions including the local Methodist vestry.

The text of Go Set a Watchman is strangely mined with violence—nouns and verbs of combat and death:

She could have added another scalp to her belt, but after years of tactical study Jean Louise knew her enemy. Although she could rout her…the last time she skirmished with Alexandra was when her brother died.

The writing throughout feels like what it clearly was, the unmediated responses of an observant young aspiring author who, having gone to try her luck in New York, comes home to Alabama for a visit and notices things with new eyes, circumstances almost identical to the ones she then puts in her novel: the real Harper Lee had a brother who died of an aneurysm, a lawyer father, a Methodist minister, and so on. The reader doesn’t doubt that Mr. Lee, like Mr. Finch, was actually reading about the Hiss case when his daughter took note of it.

4.

It’s the change in the character of Atticus that readers have found shocking. The mistaking of a literary character “Atticus” for an actual, inspiring figure is strange in itself. We might read about Gandhi in a book and be inspired to a moral or nonviolent life, but this depends on us knowing that the character on the page is the representation of a living person. Atticus, no doubt because he was incarnated by Gregory Peck, seems to have been taken as an actual person, too, and people are outraged to learn his real views, and his condescension to and exasperation with blacks. Jean Louise herself was appalled:

The man who could not be discourteous to a ground squirrel had sat in the courthouse abetting the cause of grubby-minded little men. Many times she had seen him in the grocery store waiting his turn in line behind Negroes and God knows what.

Now he was saying things like “Do you want Negroes by the carload in our schools and churches and theaters?”

Looking back at To Kill a Mockingbird, we can see that even in that book Atticus was defined more by old-fashioned rectitude than by today’s ideas about civil rights. His handsome though preachy and sententious defense of our common humanity and the rule of law has changed in the sequel to what he takes to be wary realism: “Honey, you do not seem to understand that the Negroes down here are still in their childhood as a people.”

To be shocked by ideas expressed by Atticus in Go Set a Watchman is really to perceive the mind of the author, who is in this case evidently reporting what lots of people in the 1950s in Monroeville, Alabama, said; things probably said in California and New York too, without the excuse of local history: “You realize that our Negro population is backward, don’t you?”

Jean Louise, full of fine indignation at hearing racist talk, compares her father and other white locals to Hitler, and thinks herself more enlightened. But she expresses her unconscious sense of noblesse oblige when she tells us that her father is a hero because he consents to wait his turn in line with black people. “They are simple people, most of them, but that doesn’t make them subhuman,” she thinks. Lee’s own views are to be found thus embedded deeply in the vocabulary of the work: “She followed him into a dark parlor to which clung the musky sweet smell of clean Negro, snuff, and Hearts of Love hairdressing.” “Which boy was this one? He was in real dutch this time, he needed real help and what do they do but sit in the kitchen and talk NAACP….”

What Jean Louise turns out to long for is not exactly racial equality or even equal opportunity, it’s the peaceful coexistence that she felt used to exist before the NAACP meddled, when reliably upstanding figures like her father could be counted on to do the right thing, Calpurnia was there in her place, caring and trustworthy, and there was an understanding between the two races that seemed to the white people, at least, to be working fine. Now, seeing Atticus in Go Set a Watchman helping another poor black client for free, Jean Louise deplores the ingratitude of the black people: “Who were the people Calpurnia’s tribe turned to first and always? How many divorces had Atticus gotten for Zeebo? Five, at least.” Though she’s all for equality and human dignity, and believes she’s color-blind, she also thinks the Supreme Court has no right to tell Alabamans how to run their schools:

It seemed that to meet the real needs of a small portion of the population [blacks], the Court set up something horrible that could—that could affect the vast majority of folks. Adversely, that is. Atticus, I don’t know anything about it—all we have is the Constitution between us and anything some smart fellow wants to start, and there went the Court just breezily canceling one whole amendment, it seemed to me.

She’s talking about the Tenth Amendment, which establishes states’ rights. Most shockingly, it is made plain that both Watchman and Mockingbird are not pleading a case for civil rights as we normally understand them, but instead for a return to the kinder, gentler times that privileged people like the Finches enjoyed before the civil rights movement and the interference of the Supreme Court. Jean Louise reproaches people like her father for not having treated African-Americans better, which would have forestalled all this: “Has anybody, in all the wrangling and high words over states’ rights and what kind of government we should have, thought about helping the Negroes?” But for her the truly upsetting thing is the discovery that Daddy isn’t perfect.

This Issue

September 24, 2015

Urge

Hitler’s World

Trump