Nothing can be known about the future, thought Hitler, except the limits of our planet: “the surface area of a precisely measured space.” Ecology was scarcity, and existence meant a struggle for land. The immutable structure of life was the division of animals into species, condemned to “inner seclusion” and an endless fight to the death. Human races, Hitler was convinced, were like species. The highest races were still evolving from the lower, which meant that interbreeding was possible but sinful. Races should behave like species, like mating with like and seeking to kill unlike. This for Hitler was a law, the law of racial struggle, as certain as the law of gravity. The struggle could never end, and it had no certain outcome. A race could triumph and flourish and could also be starved and extinguished.

In Hitler’s world, the law of the jungle was the only law. People were to suppress any inclination to be merciful and were to be as rapacious as they could. Hitler thus broke with the traditions of political thought that presented human beings as distinct from nature in their capacity to imagine and create new forms of association. Beginning from that assumption, political thinkers tried to describe not only the possible but the most just forms of society. For Hitler, however, nature was the singular, brutal, and overwhelming truth, and the whole history of attempting to think otherwise was an illusion. Carl Schmitt, a leading Nazi legal theorist, explained that politics arose not from history or concepts but from our sense of enmity. Our racial enemies were chosen by nature, and our task was to struggle and kill and die.

“Nature,” wrote Hitler, “knows no political boundaries. She places life forms on this globe and then sets them free in a play for power.” Since politics was nature, and nature was struggle, no political thought was possible. This conclusion was an extreme articulation of the nineteenth-century commonplace that human activities could be understood as biology. In the 1880s and 1890s, serious thinkers and popularizers influenced by Charles Darwin’s idea of natural selection proposed that the ancient questions of political thought had been resolved by this breakthrough in zoology. When Hitler was young, an interpretation of Darwin in which competition was identified as a social good influenced all major forms of politics.

For Herbert Spencer, the British defender of capitalism, a market was like an ecosphere where the strongest and best survived. The utility brought by unhindered competition justified its immediate evils. The opponents of capitalism, the socialists of the Second International, also embraced biological analogies. They came to see the class struggle as “scientific,” and man as one animal among many, instead of a specially creative being with a specifically human essence. Karl Kautsky, the leading Marxist theorist of the day, insisted pedantically that people were animals.

Yet these liberals and socialists were constrained, whether they realized it or not, by attachments to custom and institution; mental habits that grew from social experience hindered them from reaching the most radical of conclusions. They were ethically committed to goods such as economic growth or social justice, and found it appealing or convenient to imagine that natural competition would deliver these goods. Hitler entitled his book Mein Kampf—My Struggle. From those two words through two long volumes and two decades of political life, he was endlessly narcissistic, pitilessly consistent, and exuberantly nihilistic where others were not. The ceaseless strife of races was not an element of life, but its essence.

To say so was not to build a theory but to observe the universe as it was. Struggle was life, not a means to some other end. It was not justified by the prosperity (capitalism) or justice (socialism) that it supposedly brought. Hitler’s point was not at all that the desirable end justified the bloody means. There was no end, only meanness. Race was real, whereas individuals and classes were fleeting and erroneous constructions. Struggle was not a metaphor or an analogy, but a tangible and total truth. The weak were to be dominated by the strong, since “the world is not there for the cowardly peoples.” And that was all that there was to be known and believed.

Hitler’s worldview dismissed religious and secular traditions, and yet relied upon both. Though he was not an original thinker, he brought a certain resolution to a crisis of both thought and faith. Like many before him he sought to bring the two together. What he meant to engineer, however, was not an elevating synthesis that would rescue both soul and mind but a seductive collision that destroyed both. Hitler’s racial struggle was supposedly sanctioned by science, but he called its object “daily bread.” With these words, he was summoning one of the best-known Christian texts, while profoundly altering its meaning. “Give us this day,” ask those who recite the Lord’s Prayer, “our daily bread.” In the universe the prayer describes, there is a metaphysics, an order beyond this planet, notions of good that proceed from one sphere to another. Those saying the Lord’s Prayer ask that God “forgive us our debts, as we also have forgiven our debtors. And lead us not into temptation, but deliver us from evil.” In Hitler’s “struggle for the riches of nature,” it was a sin not to seize everything possible, and a crime to allow others to survive. Mercy violated the order of things because it allowed the weak to propagate. Rejecting the biblical Commandments, said Hitler, was what human beings must do. “If I can accept a divine Commandment,” he declared, “it’s this one: ‘Thou shalt preserve the species.’”

Advertisement

Hitler exploited images and tropes that were familiar to Christians: God, prayers, original sin, commandments, prophets, chosen people, messiahs—even the familiar Christian tripartite structure of time: first paradise, then exodus, and finally redemption. We live in filth, and we must strain to purify ourselves and the world so that we might return to paradise. To see paradise as the battle of the species rather than the concord of creation was to unite Christian longing with the apparent realism of biology. The war of all against all was not terrifyingly purposeless, but instead the only purpose to be had in the universe. Nature’s bounty was for man, as in Genesis, but only for the men who follow nature’s law and fight for nature. As in Genesis, so in My Struggle, nature was a resource for man: but not for all people, only for triumphant races. Eden was not a garden but a trench.

Knowledge of the body was not the problem, as in Genesis, but the solution. The triumphant should copulate. After murder, Hitler thought, the next human duty was sex and reproduction. In his scheme, the original sin that led to the fall of man was of the mind and soul, not of the body. For Hitler, our unhappy weakness was that we can think, realize that others belonging to other races can do the same, and thereby recognize them as fellow human beings. Humans left Hitler’s bloody paradise not because of carnal knowledge. Humans left paradise because of the knowledge of good and evil.

When paradise falls and humans are separated from nature, a character who is neither human nor natural, such as the serpent of Genesis, takes the blame. If humans were in fact nothing more than an element of nature, and nature was known by science to be a bloody struggle, something beyond nature must have corrupted the species. For Hitler the bringer of the knowledge of good and evil on the earth, the destroyer of Eden, was the Jew. It was the Jew who told humans that they were above other animals, and had the capacity to decide their future for themselves. It was the Jew who introduced the false distinction between politics and nature, between humanity and struggle. Hitler’s destiny, as he saw it, was to redeem the original sin of Jewish spirituality and restore the paradise of blood. Since Homo sapiens can survive only by unrestrained racial killing, a Jewish triumph of reason over impulse would mean the end of the species. What a race needed, thought Hitler, was a “worldview” that permitted it to triumph, which meant, in the final analysis, “faith” in its own mindless mission.

Hitler’s presentation of the Jewish threat revealed his particular amalgamation of religious and zoological ideas. If the Jew triumphs, Hitler wrote, “then his crown of victory will be the funeral wreath of the human species.” On the one hand, Hitler’s image of a universe without human beings accepted science’s verdict of an ancient planet on which humanity had evolved. After the Jewish victory, he wrote, “earth will once again wing its way through the universe entirely without humans, as was the case millions of years ago.” At the same time, as he made clear in the very same passage of My Struggle, this ancient earth of races and extermination was the Creation of God. “Therefore I believe myself to be acting according to the wishes of the Creator. Insofar as I restrain the Jew, I am defending the work of the Lord.”

Hitler saw the species as divided into races, but denied that the Jews were one. Jews were not a lower or a higher race, but a nonrace, or a counterrace. Races followed nature and fought for land and food, whereas Jews followed the alien logic of “un-nature.” They resisted nature’s basic imperative by refusing to be satisfied by the conquest of a certain habitat, and they persuaded others to behave similarly. They insisted on dominating the entire planet and its peoples, and for this purpose invented general ideas that draw the races away from the natural struggle. The planet had nothing to offer except blood and soil, and yet Jews uncannily generated concepts that allowed the world to be seen less as an ecological trap and more as a human order. Ideas of political reciprocity, practices in which humans recognize other humans as such, came from Jews.

Advertisement

Hitler’s basic critique was not the usual one that human beings were good but had been corrupted by an overly Jewish civilization. It was rather that humans were animals and that any exercise of ethical deliberation was in itself a sign of Jewish corruption. The very attempt to set a universal ideal and strain toward it was precisely what was hateful. Heinrich Himmler, Hitler’s most important deputy, did not follow every twist of Hitler’s thinking, but he grasped its conclusion: ethics as such was the error; the only morality was fidelity to race. Participation in mass murder, Himmler maintained, was a good act, since it brought to the race an internal harmony as well as unity with nature. The difficulty of seeing, for example, thousands of Jewish corpses marked the transcendence of conventional morality. The temporary strains of murder were a worthy sacrifice to the future of the race.

Any nonracist attitude was Jewish, thought Hitler, and any universal idea a mechanism of Jewish dominion. Both capitalism and communism were Jewish. Their apparent embrace of struggle was simply cover for the Jewish desire for world domination. Any abstract idea of the state was also Jewish. “There is no such thing,” wrote Hitler, “as the state as an end in itself.” As he clarified, “the highest goal of human beings” was not “the preservation of any given state or government, but the preservation of their kind.” The frontiers of existing states would be washed away by the forces of nature in the course of racial struggle: “One must not be diverted from the borders of Eternal Right by the existence of political borders.”

If states were not impressive human achievements but fragile barriers to be overcome by nature, it followed that law was particular rather than general, an artifact of racial superiority rather than an avenue of equality. Hans Frank, Hitler’s personal lawyer and during World War II the governor-general of occupied Poland, maintained that the law was built “on the survival elements of our German people.” Legal traditions based on anything beyond race were “bloodless abstractions.” Law had no purpose beyond the codification of a Führer’s momentary intuitions about the good of his race. The German concept of a Rechtsstaat, a state that operated under the rule of law, was without substance. As Carl Schmitt explained, law served the race, and the state served the race, and so race was the only pertinent concept. The idea of a state held to external legal standards was a sham designed to suppress the strong.

Insofar as universal ideas penetrated non-Jewish minds, claimed Hitler, they weakened racial communities to the profit of Jews. The content of various political ideas was beside the point, since all were merely traps for fools. There were no Jewish liberals and no Jewish nationalists, no Jewish messiahs and no Jewish Bolsheviks: “Bolshevism is Christianity’s illegitimate child. Both are inventions of the Jew.” Hitler saw Jesus as an enemy of Jews whose teachings had been perverted by Paul to become one more false Jewish universalism, that of mercy to the weak. From Saint Paul to Leon Trotsky, maintained Hitler, there were only Jews who adopted various guises to seduce the naive. Ideas had no historical origins and no connection to the succession of events or to the creativity of individuals. They were simply tactical creations of the Jews, and in this sense they were all the same.

Indeed, for Hitler there was no human history as such. “All world- historical events,” he claimed, “are nothing more than the expression of the self-preservation drive of the races, for better or for worse.” What must be registered from the past was the ceaseless attempt of Jews to warp the structure of nature. This would continue so long as Jews inhabited the earth. “It is Jewry,” said Hitler, “that always destroys this order.” The strong should starve the weak, but Jews could arrange matters so that the weak starve the strong. This was not an injustice in the normal sense, but a violation of the logic of being. In a universe warped by Jewish ideas, struggle could yield unthinkable outcomes: not the survival of the fittest, but the starvation of the fittest.

From this it followed that Germans would always be victims so long as Jews existed. As the highest race, Germans deserved the most and had the most to lose. The unnatural power of Jews “murders the future.”

Though Hitler strove to define a world without history, his ideas were altered by his own experiences. World War I, the bloodiest in history, fought on a continent that thought itself civilized, undid the broad confidence among many Europeans that strife was all to the good. Some Europeans of the far right or the far left, however, drew the opposite lesson. The bloodshed, for them, had not been extensive enough, and the sacrifice incomplete. For the Bolsheviks of the Russian Empire, disciplined and voluntarist Marxists, the war and the revolutionary energies it brought were the occasion to begin the socialist reconstruction of the world. For Hitler, as for many other Germans, the war ended before it was truly decided, the racial superiors taken from the battlefield before they had earned their due.

Of course, the sentiment that Germany should win was widespread, and not only among militarists or extremists. Thomas Mann, the greatest of the German writers and later an opponent of Hitler, spoke of Germany’s “rights to domination, to participate in the administration of the planet.” Edith Stein, a brilliant German philosopher who developed a theory of empathy, considered “it out of the question that we will now be defeated.” After Hitler came to power she was hunted down in her convent and murdered as a Jew.

For Hitler, the conclusion of World War I demonstrated the ruin of the planet. Hitler’s understanding of its outcome went beyond the nationalism of his fellow Germans, and his response to defeat only superficially resembled the general resentment about lost territories. For Hitler, the German defeat demonstrated that something was crooked in the whole structure of the world; it was the proof that Jews had mastered the methods of nature. If a few thousand German Jews had been gassed at the beginning of the war, he maintained, Germany would have won. He believed that Jews typically subjected their victims to starvation and saw the British naval blockade of Germany during (and after) World War I as an application of this method. It was an instance of a permanent condition and the proof of more suffering to come. So long as Jews starved Germans rather than Germans starving whom they pleased, the world was in disequilibrium.

From the defeat of 1918 Hitler drew conclusions about any future conflict. Germans would always triumph if Jews were not involved. Yet since Jews dominated the entire planet and had penetrated the minds of Germans with their ideas, the struggle for German power must take two forms. A war of simple conquest, no matter how devastatingly triumphant, could never suffice. In addition to starving inferior races and taking their land, Germans needed to simultaneously defeat the Jews, whose global power and insidious universalism would undermine any such healthy racial campaign. Thus Germans had the rights of the strong against the weak, and the rights of the weak against the strong. As the strong, they needed to dominate the weaker races they encountered; as the weak, they had to liberate all races from Jewish domination. Hitler thus united two great motivating forces of the world politics of his century: colonialism and anticolonialism.

Hitler saw both the struggle for land and the struggle against the Jews in drastic, exterminatory terms, and yet he saw them differently. The struggle against inferior races for territory was a matter of the control of parts of the earth’s surface. The struggle against the Jews was ecological, since it concerned not a specific racial enemy or territory but the conditions of life on earth. The Jews were “a pestilence, a spiritual pestilence, worse than the Black Death.” Since they fought with ideas, their power was everywhere, and anyone could be their knowing or unknowing agent. The only way to remove such a plague was to eradicate it at the source. “If Nature designed the Jew to be the material cause of the decline and fall of the nations,” said Hitler, “it provided these nations with the possibility of a healthy reaction.” The elimination had to be complete: if one Jewish family remained in Europe, this could infect the entire continent.

The fall of man could be undone; the planet could be healed. “A people that is rid of its Jews,” said Hitler, “returns spontaneously to the natural order.”

Hitler’s views of human life and the natural order were total and circular. All questions about politics were answered as if they were questions about nature; all questions about nature were answered by reference back to politics. The circle was drawn by Hitler himself. If politics and nature were not sources of experience and perspective but empty stereotypes that existed only in relation to each other, then all power rested in the hands of those who circulated such stereotypes. Reason was replaced by references, argumentation by incantation. The “struggle,” as the title of the book gave away, was “mine”: Hitler’s. The totalistic idea of life as struggle placed all power to interpret any event in the mind of its author.

Equating nature and politics abolished not only political but also scientific thought. For Hitler, science was a completed revelation of the law of racial struggle, a finished gospel of bloodshed, not a process of hypothesis and experiment. It provided a vocabulary about zoological conflict, not a fount of concepts and procedures that allowed ever more extensive understanding. It had an answer but no questions. The task of man was to submit to this creed, rather than willfully impose specious Jewish thinking upon nature. Because Hitler’s worldview required a single circular truth that embraced everything, it was vulnerable to the simplest ideas of pluralism: for example, that humans might change their environment in ways that might, in turn, change society. If science could change the ecosystem so that human behavior was altered, then all of his claims were groundless. Hitler’s logical circle, in which society was nature because nature was society, in which men were beasts because beasts were men, would be broken.

Hitler accepted that scientists and specialists had purposes within the racial community: to manufacture weapons, to improve communications, to advance hygiene. Stronger races should have better guns, better radios, and better health, the better to dominate the weaker. He saw this as a fulfillment of nature’s command to struggle, not as a violation of its laws. Technical achievement was proof of racial superiority, not evidence of the advance of general scientific understanding. “Everything that we today admire on this earth,” wrote Hitler, “the scholarship and art, the technology and inventions, are nothing more than the creative product of a few peoples, and perhaps originally of a single race.” No race, however advanced, could change the basic structure of nature by any innovation. Nature had only two variants: the paradise in which higher races slaughter the lower, and the fallen world in which supernatural Jews deny higher races the bounty they are due and starve them when possible.

Hitler understood that agricultural science posed a specific threat to the logic of his system. If humans could intervene in nature to create more food without taking more land, his whole system collapsed. He therefore denied the importance of what was happening before his eyes, the science of what was later called the “Green Revolution”: the hybridization of grains, the distribution of chemical fertilizers and pesticides, the expansion of irrigation. Even “in the best case,” he insisted, hunger must outstrip crop improvements. There was “a limit” to all scientific improvements. Indeed, all of “the scientific methods of land management” had already been tried and had failed. There was no conceivable improvement, now or in the future, that would allow Germans to be fed “from [their] own land and territory.” Food could only be safeguarded by conquest of fertile territory, not by science that would make German territory more fertile. Jews deliberately encouraged the contrary belief in order to dampen the German appetite for conquest and prepare the German people for destruction. “It is always the Jew,” wrote Hitler in this connection, “who seeks and succeeds in implanting such lethal ways of thinking.”

Hitler had to defend his system from human discovery, which was as much of a problem for him as human solidarity. Science could not save the species because, in the final analysis, all ideas were racial, nothing more than aesthetic derivatives of struggle. The contrary notion, that ideas could actually reflect nature or change it, was a “Jewish lie” and a “Jewish swindle.” Hitler maintained that “man has never conquered nature in any matter.” Universal science, like universal politics, must be seen not as human promise but as Jewish threat.

The world’s problem, as Hitler saw it, was that Jews falsely separated science and politics and made delusive promises for progress and humanity. The solution he proposed was to expose Jews to the brutal reality that nature and society were one and the same. They should be separated from other people and forced to inhabit some bleak and inhospitable territory. Jews were powerful in that their “un-nature” drew others to them. They were weak in that they could not face brutal reality. Resettled to some exotic locale, they would be unable to manipulate others with their unearthly concepts, and would succumb to the law of the jungle. Hitler’s first obsession was to expel the Jews to an extreme natural setting, “an anarchic state on an island.” Later his thoughts turned to the wastes of Siberia. It was “a matter of indifference,” he said, whether Jews were sent to one or the other.

In August 1941, about a month after Hitler made that remark, his men began to shoot Jews in massacres on the scale of tens of thousands at a time, in the middle of Europe, in a setting they had themselves made anarchic, over pits dug in the black earth of Ukraine.

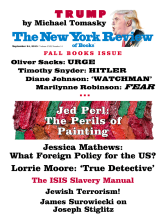

This Issue

September 24, 2015

Urge

Trump