Like the reports of the end of history that we have been hearing, the many reports of the death of painting have no basis in reality. Painting flourishes—in the studios of artists, in galleries in New York’s Chelsea, Lower East Side, Williamsburg, and Bushwick, as well as in galleries around the world. Museums, whatever their ever-deepening engagement with installation and performance art and the cavernous spaces designed to accommodate such work, are hardly neglecting contemporary painting.

Since last summer, the Museum of Modern Art has presented a vast Sigmar Polke retrospective as well as “The Forever Now: Contemporary Painting in an Atemporal World.” A continuing fascination with painting fueled “In the Studio,” a historical survey of paintings of artists’ workplaces, mounted at the Gagosian Gallery on West 21st Street over the winter. And this summer the New Museum—a New York institution that prides itself on its innovative programming—has organized a retrospective of the contemporary German painter Albert Oehlen. Although it sometimes seems that anything but painting is what arts professionals are most eager to put before the public, the truth is that when artists, critics, and curators want to take the pulse of contemporary art, painting inspires much of the deepest, most heartfelt, and heated discussion.

David Salle—a painter who came to prominence a generation ago, at another moment when painting was said by many to be dead—recently wrote that “the Web’s frenetic sprawl is opposite to the type of focus required to make a painting, or, for that matter, to look at one.” I think he’s right. And for this very reason painting becomes a steadying force—a source of stability in an art world where everything can seem to be up for grabs. With performances, moving images, live and recorded music and sounds, as well as just about anything that can be pulled off the Internet appearing in the galleries, it is more difficult than ever before to grapple with the fundamental questions of style and meaning that are integral to art. The essentially plainspoken, artisanal nature of painting, which can’t avoid registering all the pressures of the world around us, albeit sometimes by simply setting them aside, can help visitors to galleries and museums understand what is happening in art today.

It may well be this sense of painting’s clarifying power that motivated the Museum of Modern Art to mount “The Forever Now,” the first exhibition in the museum in at least thirty years that offered an expansive survey of contemporary painting. Laura Hoptman, who organized “The Forever Now,” says as much in her introduction to the exhibition catalog. “The obsession with recuperating aspects of the past is the condition of culture in our time,” she declares, “yet it appears in contemporary art at this moment most clearly in the field of painting.” Although Hoptman and I do not agree when it comes to how to evaluate contemporary painting—we are interested in very different artists—I can see that we are reacting to the same seismic shifts.

For hundreds of years—probably since the Renaissance—a painter’s style has implied a certain set of values, with Classicism, Romanticism, Naturalism, Cubism, and Expressionism each reflecting a generally agreed-upon worldview. In today’s anything-goes art world a particular pictorial style no longer implies a particular worldview or set of values. Style has been dissociated from substance, so that while for one artist classicism still represents the timeless order it did for Poussin, for another artist classicism is a camp joke about the banality of history, and for yet another its muffled emotions suggest robotic, posthuman anomie. It is no longer enough for an artist to begin by embracing a style. Now an artist who believes in the inextricable link between style and substance has to almost single-handedly reconstruct the substance of that style.

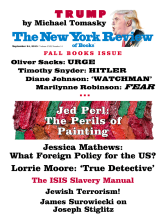

This Issue

September 24, 2015

Urge

Hitler’s World

Trump

-

*

Art in America, May 2009. ↩