“Thomas Bewick is an inventor, and the first wood-cutter in the world!” John James Audubon, the great recorder of America’s birds, saluted his equivalent in Britain in these terms in his journal at the end of a visit to Newcastle upon Tyne in 1827. In other words, Bewick was not simply an engraver of wooden blocks for printing, he was, in 1820s terms, one of the men of the day. This was, as Bewick himself wrote, an “age of mechanical improvement.”1

Two years earlier, not forty miles from Newcastle, George Stephenson had presented the world with the first public railway. Whether he was to be thanked likewise for the safety lamp that was revolutionizing the coal mines of the region, or whether credit here was due to the charismatic Humphry Davy, was a matter for loud debate. Busts of James Watt and Benjamin Franklin, earlier deliverers of innovation, stood on the mantelpiece of every social optimist. Keeping them company were the inventors of the arts. Audubon, reflecting on “the intrinsic value…to the world” of the seventy-three-year-old Northumberland man he had just met, compared him to Walter Scott, the “learned” and “brilliant” fictionalizer of British history.

Thomas Bewick, however, was for Audubon “a son of Nature.” Publishing his surveys of mammals and then of British birds between 1790 and 1804, with hundreds of species pictured in wood engravings of unprecedented precision and vitality, Bewick had offered modern readers an expanded appreciation of the creatures with whom they shared the earth. An equally important factor in his rise to fame were the “tail-pieces” concluding each species entry, tiny and captivating distillations of life in the British countryside. Bewick had been able to “invent”—to come upon, in the verb’s original sense—this new wealth of imaginative experience not because he was learned like Scott, but rather because he was singularly well acquainted with the fields, woods, and hills, having been brought up on a farmstead ten miles up the Tyne from Newcastle.

We no longer nowadays salute “Nature” with the unhesitating confidence invested in the concept by Audubon or by writers such as William Wordsworth, another of Bewick’s numerous admirers. And yet Diana Donald’s impressive recent study, The Art of Thomas Bewick, demonstrates the surprising resilience of the American visitor’s assessment. At the end of her scrupulous inquiry into the political, religious, and cultural circumstances in which Bewick’s work was undertaken, the Northumbrian natural historian still stands, however we interpret him, as an innovator rather than an imitator, and as an artist who worked, as much as any artist can, from freshly won experience rather than by cleaving to cultural precedent.

For Audubon to hail Bewick as “the first wood-cutter” was to recognize that he had used wood to deliver effects never realized before. Back in the Renaissance, printmakers in Europe carved away at blocks of pear wood to deliver the long-flowing, calligraphic lines visible, say, in Dürer’s Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse, or in the equally dynamic images of Hans Baldung Grien or Hendrick Goltzius—the craftsmen’s knives and chisels working along with the grain of the dense, smooth wood. In early modern art there was no longer a place for such expressive uses of the medium. Oil painting became entrenched as high art, and copperplate engraving presented the surest technique for monochrome reproduction of its effects. So after 1600 the woodblock was relegated to menial service. Since, unlike the copperplate, it could be integrated in a single printing with adjacent blocks of text, it supplied the chunky, easy-to-read pictures and heraldic devices that adorned tracts, ballads, children’s primers, and the like. Boxwood from Turkey, harder than pear, became the main resource, exported to jobbing print workshops across Europe.

In one of these, three quarters of the way from London to Edinburgh, the young Thomas Bewick took to carving into the end grain of the block, rather than attacking one of its plank faces. It seems to have been the unprompted impulse of a handyman with a uniquely keen eye, one dissatisfied with the quality of line that any more yielding surface could deliver. The development of a novel texture of print was gradual across the decades that followed Bewick’s entry into the Newcastle shop of Ralph Beilby as a fourteen-year-old apprentice in 1767. But it was helped by the variety of jobs that Beilby took on—engraving anything from clock faces to dog collars, bank notes to wine goblets—a range of services Bewick would continue to provide to his fellow citizens after he took control of the business thirty years later.

Bewick found that the needle-fine points employed to scratch designs into copper, silver, brass, and glass could be adapted to score the fine-grained boxwood with microscopic precision, and that the resulting “cuts” or printing blocks were resilient enough to deliver a near-endless number of reliable impressions. A technique arose that could outperform the copperplate.

Advertisement

Unlike the eighteenth-century copperplate, however, the new “wood engraving” bore only an indirect relationship to painting. Etchers knew how to work their plates with systems of cross-hatching that simulated the look of modeling in oils. But Old Master canvases played little part in Bewick’s provincial formation. Though he journeyed to London at the age of twenty-three, he gladly quit the capital nine months later, preferring to remain in a Newcastle that had, as he told a friend, “fewer admirers of the Arts” than any comparable British city. Instead, he cultivated an ethos of truth to his chosen medium. “I have long been of opinion,” he wrote in a memoir addressed to his daughter, “that the cross hatching of wood cuts, for book work, was a waste of time, as every effect can be much easier obtained by plain parallel lines, and that the other way was not the legitimate object of wood engraving,” adding that it had been his “ardent desire to see the stroke engraving on wood carried to the utmost perfection.”

A cut, by definition, separates what was unseparated before; a stroke, by connotation, is a pleasurable action, an unhindered impulse running from shoulder to hand to tool. The new art that Bewick developed was at once a probing of the world and a calligraphy. Among the four-hundred-odd species in his History of British Birds, Bewick describes garden warblers. These are small, inconspicuous birds. Although far from rare, they seek cover in foliage and are so elusive that Bewick was able only once, briefly, to observe a shot specimen, without time to supplement his few live sightings by sketching in detail. Despite this, the resulting woodcut is, Diana Donald observes, “one of Bewick’s most striking successes…. He captures perfectly the shape, plumage and attitude of this notoriously featureless species.”

Bewick did so with tiny ripples of wood-scoring serried on average about twenty to the quarter-inch, responding to the overlap of each feather and often to the fine barbs that run from its quill. At the same time these grooves gently modulate in depth to convey the swell of the shoulders and crown, while they are half scratched through on the breast, this being “dingy white, a little inclining to brown” according to Bewick’s accompanying text: among his ambitions for wood engraving was to succeed in suggesting color. Above all, the cock of the bird’s head and a nicked highlight in the eye convey the look of a species that doesn’t much like to be looked at. Donald cites a contemporary of Bewick’s who remarked that he alone among natural history illustrators could help the observer make out a bird “even at a distance, as sailors say, by ‘the cut of his jib’…his je ne sçais quoi.”

In fact, Donald compares this woodcut to a color illustration of the same bird from a handbook published in 1938, by which time artists had photography to assist them, and finds that Bewick’s is the more informative. This verdict comes in “A Commentary on Bewick’s Representation of Species” that forms an appendix to her text and performs an itemized fact-check. It enhances the reader’s respect for Bewick’s matchlessly sharp eye, though occasionally Donald—an art historian whose son is an ornithologist—chooses to upbraid him. For example, he “misleadingly” depicts a spoonbill “against a background of rocky coast” when marshes are its habitat: or supposes the aforementioned illustration to represent a “passerine” rather than a “garden” warbler, where modern science recognizes only one species. All this makes for an unusual venture in art studies, a field in which present-day writers are generally more comfortable with allusions to “reality effects” rather than with assessing any correspondence art might have with reality.

And yet though Donald sometimes talks of “realism,” that is not exactly the term for Bewick’s project. The four jolly spiral squiggles beneath the warbler make an invigorating contrast to its exquisitely rendered plumage, but they hardly come together as a plausible branch for the bird to stand on. In one sense, the surrounding variegation of hacks, streaks, and curling strokes composes into a habitat for the bird: it was one of Bewick’s innovations, thus to convey the proper environmental context of a species.

Yet study those marks more closely—for Bewick is constantly inviting you to reach for the magnifying glass—and the habitat resolves itself into a decorative bricolage, devoid of internal spatial logic. That assemblage of marks attaches itself to the specimen much in the way that in heraldry, the “supporters” (lions rampant, for instance) and the “compartment” (the grassy knoll beneath their feet) surround an escutcheon, providing the entire unit for reproduction with a similarly irregular outline. The hierarchy of meanings in a Bewick woodcut and its relation to the paper it sits on surely derive from his experience of transferring designs to vessels, clocks, and the like, rather than from a kinship with framed pictures.

Advertisement

The issue is further complicated, however, by the distinctly painterly trick Bewick engineered of planing down sections of the block so that they would print more faintly—an innovation that, in the case of the warbler image, creates the atmospheric haze distancing the trees seen at top left behind the wattle fence. His project thus cuts across our current categories of high art, of signwork, and of scientific illustration—a conceptual challenge that Donald sets out to confront. Her interpretation points out that Bewick not only had his feet firmly planted in a working knowledge of the countryside, as the son of a Northumberland tenant farmer. He also lent his vocal powers to the debating clubs of a Newcastle that buzzed with progressive ideas. (Jean-Paul Marat, the subsequent Jacobin journalist, was based in the city during the early 1770s.) Bewick’s own politics argued for “the march of intellect” and “the liberties of mankind”—he heroized the American Revolution—while defending the rights of property and taking the experience of “the man of industry, the plain plodding farmer” as the measure of social justice. Enlightenment, therefore, from this distinctive northern English perspective, was not to be sought in abstract philosophic schemes but in solidly grounded improvements and discoveries.

So it was with zoology. Bewick wrote skeptically about the taxonomic theories of so-called “Garret Naturalists” in one of his prefaces to British Birds:

Systems have been formed and exploded, and new ones have appeared in their stead; but like skeletons injudiciously put together, they give but an imperfect idea of that order and symmetry to which they are intended to be subservient.

He was content if with his own “out-door naturalism,” based as far as possible on direct observation, he could delineate and label items of evidence in a sequence appealing to everyday instincts—starting with “The Golden Eagle,” the most kingly of native species, and carrying on through to “The Least Willow Wren.” On some higher plane, “order and symmetry” undoubtedly existed, for Bewick was a reverent deist who sooner saw God’s hand in “the great book of Nature” than in the Bible. But “to follow [Nature] into all her recesses would be an endless task,” a second preface concludes, gesturing in a mode of sublime reverie toward the migrations of “countless multitudes of birds, wafted, like the clouds, around the globe.”

Each entry in the two volumes of the Birds begins with a “cut,” beneath which capital letters definitively announce the species identity—“THE ROOK,” for instance. The effect is somewhat like an old inn sign, with that spirit so distinctive to folk art, of a creature receiving its first naming and proclamation. But then, after a page or two of informative text, there is the pictorial equivalent of a word left indefinite—the untitled engraving Bewick described as his “tail-piece.” End decorations with freeform borders (“vignettes”), a convention as old as printing, here took on unprecedented potency. Blessed with vigor as well as keen eyes—a year before his death, it was “a tall, stout man” that Audubon met, “full of life” and “active and prompt in his labours”—Bewick poured his surplus energies into unbidden, miniature caprices that played with and half resisted the will to interpret.

Typically, he would haul out from his imagination’s stockroom a farmyard, field, or country lane, or maybe a streambank or seashore; or would dream of dwellings and their erection, their inhabitation and eventual ruin; or at last of the cemetery. These scenes might crystallize around busy little characters, most often the “plain plodding” types who were the norm of his social experience. In the vignettes, the “sturdily independent or raffish lives” (as Donald puts it) of these farming folk or children or vagrants intersect with the lives of familiar animals and with the rains, winds, and snows of phlegmatic northern England. For those who came after Bewick, the wealth of late-eighteenth-century rural experience recorded in these exquisite engravings would get suffused with nostalgia. They would become poignant trophies, at once primal and naive: as much as things were being seen for the first time, they were being seen for the last.

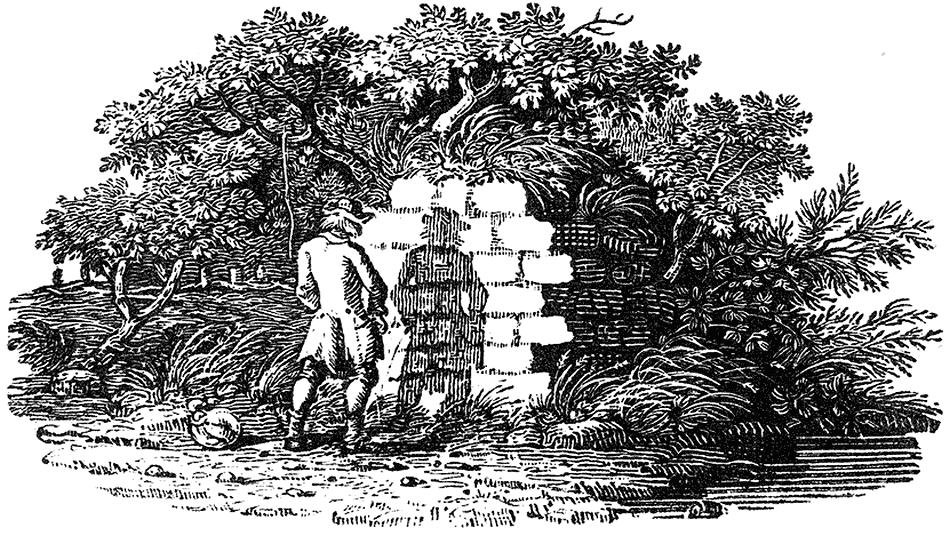

What did the tail-pieces intend, however? They resonate on various levels—not least in fact in their ripostes to sentimentality. Tourists have long visited Northumberland for the sake of Hadrian’s Wall, Britain’s outstanding relic of Roman occupation. Bewick shows a traveler actively addressing himself to one of the wall’s masonry fragments, but to relieve himself and by no means to gawp in awe. The visual proposition is droll and somewhat gross—a great deal of piss, shit, and vomit is scattered through Bewick’s imagery—yet even so, it has a lyrical air: the wind rustles the bushes, the sun brightly shines, there is empathy with that averted figure and his simple pleasure of bladder relief. And underlying that, there is surely a foretaste of Shelley’s “Ozymandias” and its withering mockery of the pretensions of ancient tyranny. (Elsewhere, Bewick shows a tottering monument inscribed Splendid victory, against which a passing donkey scratches his behind.)

There are simple, carefree pleasures—“No artist has ever given a more convincing portrayal of children at play than Bewick,” writes Donald—and within the same worldly weave, there is cruelty: the waggoner who whips his overladen nag, or the crowd circled around an outdoor cockfight, ignoring what God offers them, the perfect rainbow above their heads. Donald, deeply versed in British cultural themes of the two centuries spanned by Bewick’s life, points out that compassion to animals was becoming prominent among them, and that on some level these are conscience-stirring pictorial parables.

Indeed, any reading of My Life, the memoir Bewick wrote for his daughter, or of Nature’s Engraver, the engaging biography that Jenny Uglow brought out in 2006, will confirm that the engraver was plentifully opinionated on all issues, a good citizen and family man superabundant with his own rectitude. Donald also notes the social rebuke implied when, for instance, a beggar is shown licking at scraps outside the walls of a grandee’s mansion, upon which a peacock struts. And yet the riposte here is partly an internal affair, counterparting a “head-piece” three pages earlier, which pictures THE PEACOCK in all his visual extravagance. The tail-pieces are, as Donald acknowledges, “polysemic,” and in this sense remain richer in content than their progenitor’s conversation.

You can read them as you will: they are gratuitous flights of the imagination. In that, you might say, they are preeminently aesthetic and thus diametrically contrasted to the species images with their precise descriptive function. But the logical status of each line of production is equally remote from the aesthetics of painting, the dominant “fine art.” In 1984, Charles Rosen and Henri Zerner proposed that in a Bewick engraving, in contrast to a framed canvas,

the image, defined from its center rather than its edges, emerges from the paper as an apparition or a fantasy. The uncertainty of contour often makes it impossible to distinguish the edge of the vignette from the paper: the whiteness of the paper, which represents the play of light within the image, changes imperceptibly into the paper of the book, and realizes, in small, the Romantic blurring of art and reality.2

Another essay by Tom Lubbock, rerouting the arguments of Rosen and Zerner twenty-five years later, posited that each scene stood in relation to its pictured protagonist as a kind of “thought-bubble.” The ruined wall and foliage, for instance, constitute for the halted traveler “the patch of the world illuminated by the narrow beam of his present consciousness.” And in this manner, Lubbock concluded, the vignette amounted to “a definition of the mind.”3

Diana Donald does not try to rival these two provocative attempts to locate Bewick within art theory. She does however map the extensive impact the engraver had on Victorian culture, above all the resonances his work held for writers ranging from Tennyson and the Brontës to the critic John Ruskin. The last, the most difficult of devotees, sought to explain how such a “vulgar or boorish person” as Bewick could nonetheless represent the quintessence of his nation’s art. “To his utterly English mind, the straw of the sty, and its tenantry, were abiding truth…. He could draw a pig, but not an Aphrodite.” That empirical temper, claimed Ruskin, allowed for “bitter intensity of…feeling,” and he singled out as an example of “highest possible quality,” for its “feeling of melancholy,” a little tail-piece showing two horses standing in a paddock on a pelting autumn evening.

The two square inches of ink in question have a bearing on the arguments advanced by Lubbock, who speaks of images that lie raggedly on the page “like a smudge or a spillage.” This particular scene has been reduced to an almost homogenous state of twilight by close-packed horizontal grooves, and then further scratched through by diagonal slashing representing the dismal English rain. And it is much as those recent essays claim: the image pitches you into the range of awareness experienced by the sorry, long-suffering beasts; you are seduced into empathy; it seems that you are there, and that there is nowhere else to be. And yet this ink upon the paper is so very nearly a mere blemish and accident. It is a nameless whim and it need not have been at all. All that redoubles the melancholy. It seems that a disconnected, arbitrary proposition in a big blankness is as much as can be ventured. The picture opens up a mental world, and yet it can be seen as no more and no less than the big black thumbprint that from time to time intrudes on the vignettes, Bewick’s own mark canceling out Bewick’s own scene-creation.

Bewick as countryman was phlegmatic about art. Nature would always exceed us, at once grander and harsher than we could hope to represent: the rain would outlast the roofs built against it; just down the road, the graveyard would always be waiting. Bewick as citizen subscribed to the ethos of improvement. He bequeathed his successors what would become one of the leading print techniques of the nineteenth century, along with an enhanced database of zoological information: and although he seldom pictured them, he seems to have had no quarrel with the pitheads and tall chimneys sprouting up along the Tyne.

The environmental agonies that we associate with the Industrial Revolution were not exactly his, though they would follow soon after. Soon enough, also, the new zoological systematizers, the Darwinians, would supersede the “natural theology” that underpinned Bewick’s database. The “cuts,” therefore, got distanced from the settings that gave rise to them, settings Donald has now reexplained: but then, the country they contained had always seemed to reveal itself as if through a telescope. For his viewers peering in, it was rather as Auden wrote of Edward Lear: Bewick “became a land.”

-

1

Thomas Bewick, My Life, edited by Iain Bain (London: Folio Society, 1981, p. 181). ↩

-

2

“The Romantic Vignette and Thomas Bewick,” in Romanticism and Realism: The Mythology of Nineteenth-Century Art (Faber and Faber, 1984), pp. 81–84. ↩

-

3

“Defining the Vignette,” in English Graphic (Frances Lincoln, 2012), p. 137. ↩