It was the first day of medical school, and I was about to dissect the corpse of a middle-aged woman. Like all the cadavers in the anatomy lab, her head, hands, and feet were covered by gauze. The instructor pointed to an exposed arm and showed me how to cut with care, revealing the subcutaneous fat and underlying muscle. I took the scalpel and continued the dissection, exhilarated by the prospect of learning the body’s structure so I could understand its functions.

Over the following weeks, the excitement of dissection evaporated as each day I was expected to memorize the names and locations of scores of nerves, muscles, tendons, ligaments, and bones. This knowledge was tested in so-called “practicals,” where the instructor stood next to the cadaver and pointed to a body part, awaiting the answer. The relentless rote memorization made anatomy a dry, lifeless subject.

Gavin Francis’s engaging and edifying book Adventures in Human Being breathes life into the study of anatomy by situating it in the larger landscape of human experience, connecting the body to art, literature, music, astronomy, and history. Unlike most physicians whose career encompasses a single discipline, Francis has worked in pediatrics, obstetrics, geriatrics, orthopedics, and neurosurgery. An avid traveler, he served as an expedition medic in the Arctic and Antarctic, and as a physician in communities in both Africa and India.

Today Francis is a family doctor in a small inner-city clinic in Edinburgh. Over the years, he has been called to emergency situations that “are extreme and offer a heightened awareness of human lives at their most vulnerable.” While such moments are fraught and heroic, Francis notes that “some of the deepest and most rewarding insights medicine has given me have been from quieter, everyday encounters.” This breadth of clinical experience makes him a uniquely adept interpreter of the body in health and disease.

The narratives of Adventures in Being Human follow a sequence that I, along with many physicians, use to examine patients, beginning at the head and ending at the foot. In his chapter on the brain, Francis addresses electroconvulsive therapy (ECT). He explains that the treatment triggers “epileptic seizures by applying electricity to an unconscious patient’s temples—a dramatic and, to some, a frightening idea for a medical therapy.” This leads him to consider how through history different cultures searched for meaning in the grand mal seizures of epilepsy. The Greeks believed epilepsy to be a “Sacred Disease,” signifying direct communication between the material world and the spiritual realm:

Fits appear to overwhelm the flesh, as if the spirit has been possessed, or has temporarily left the body. Following a seizure many people experience a period of quiet sedation, as the brain recovers to its pre-seizure state. That seizures were once considered “sacred” is understandable—the first time I saw someone collapse with a fit, convulse, then drift off to sleep, it was as if I’d watched a process of possession, catharsis and sanctification.

Francis recounts how giving electric shocks to patients became an accepted therapy for severe depression in the modern era. In 1934, two psychiatrists in Rome—Ugo Cerletti and Lucio Bini—experimented with electricity instead of drugs to induce seizures. They first electrocuted dogs by inserting electrodes in the mouth and anus, but the animals often died from cardiac arrest. They next tried passing the current between the dogs’ temples; a similar method was used in slaughterhouses in Rome to stun pigs before killing them. Ultimately, Cerletti and Bini arrived at a range of voltage and current that shocked a person and induced an epileptic seizure without risking death.

Their studies, Francis emphasizes, were done against the backdrop of the rise of European fascism when psychiatry was becoming a tool of the state to subjugate those deemed undesirable. In 1938, Mussolini classified political dissidents as insane, and Hitler was instituting sterilization of people with schizophrenia and alcoholism. Cerletti, a subscriber to fascist periodicals, was undoubtedly aware of such immoral measures.

One of the first patients treated with ECT by Cerletti and Bini was “S.E.,” who allegedly responded to the shock by sitting up after the seizure with “a vague smile.” When asked what had happened, he replied that he didn’t know, perhaps he had been asleep. This tale may be apocryphal, because other reports have him singing a popular song or speaking in an unemotional tone about death. “But all of them agree that he became more coherent; over two subsequent months they gave him ten more shocks….” On follow-up, a year later, S.E. claimed that he was “very well,” though his wife said that “sometimes during the night he would speak as though in answer to voices.”

The uses of ECT later went beyond severe depression; it was applied as a “cure” for homosexuality, and as a punishment in state asylums for patients who would not finish a meal or who appeared threatening. In other instances, electroshock was seen as a therapeutic shortcut to limit giving expensive antidepressant drugs to the underinsured. In one program, repeated ECT was administered to a patient to reduce his cognitive function to that of an infant; this was done on the grounds that the shocks would erase the memories of disturbing experiences that led to his psychopathology. The famous Scottish-born psychiatrist Ewen Cameron, Francis writes, who promoted this strategy, “was later shown to have received funding from the CIA to develop ‘brainwashing’ techniques in which ECT would play a part.”

Advertisement

In current practice, severely depressed people are sedated and anesthetized for the treatment, and Francis contrasts this more humane approach with the depiction of ECT in stories:

The reputation of the treatment in the popular imagination has been darkened by literature: in Ken Kesey’s One Flew Over The Cuckoo’s Nest, it’s an instrument of torture, while for Sylvia Plath in The Bell Jar it’s alternately terrifying and transcendental—terrifying when administered by an uncaring doctor, and transcendental when delivered by someone more compassionate. For Plath, ECT is both sacred and profane, punishment and cure—for her fictional protagonist in The Bell Jar, it seems to have the power of both damnation and redemption. It’s notable that in many of the deeply negative accounts of ECT in literature, the recipient wasn’t sedated and anesthetized for the treatment—modern patient experience is for most people far more benign.

How ECT works is still a mystery. Francis wonders how much of its effect can be attributed to the electricity itself, to changes in neurotransmitters caused by the seizures, or even the circumstances around receiving the treatment. He acknowledges the “Freudian-minded thinkers” who propose that the “drastic nature of ECT works by offering redemption from feelings of intense guilt—a position not too distant from that of the ancient Greeks.”

My mother lived for many years with a disorder akin to multiple sclerosis. She was cared for by an attentive neurologist at Columbia University Medical Center, who judiciously outlined for her the risks and benefits of possible treatments. More than once after an appointment, my mother called me to say that she felt much stronger and in less pain.

“What new drug did the neurologist prescribe?” I asked.

“No, no medication. Just seeing her and talking with her made me feel so much better.”

Francis would have understood my mother’s response; he is acute in discussing what is often called “healing.”

Increasingly recognized in psychiatric research, it’s not the therapy that makes the biggest difference but the therapist. As in many areas of psychiatry, Freud got there first: “All physicians, yourselves included, are continually practicing psychotherapy, even when you have no intention of doing so and are not aware of it.”

He rightly concludes the chapter on ECT by noting that “there’s nothing sacred about seizures, but there just might be something sacred about a good doctor-patient relationship.”

The structure of the eye and the workings of vision have long fascinated students of the body. Francis posits sight as unique among the senses in connecting us to the cosmos:

We can taste what’s in our mouths, touch what’s within our reach, smell within hundreds of meters and hear within tens of miles. But it’s only through our vision that we are in communication with the sun and stars.

He recounts as a supporting vignette Newton’s bizarre self-experimentation to assess the reliability of his celestial observations:

When Isaac Newton was working out the motion of the planets around the sun he embarked on dramatic experiments to test the reliability of his own vision. Inserting a long, blunt needle (a “bodkin”) into his own eye socket between the bone and the eyeball, he described how wiggling it around distorted his vision.

What of the perceptions of the world of the blind when their vision is lost? Jorge Luis Borges famously inherited from his father a form of ocular degeneration that led to total blindness. Based on his clinical history, Francis speculates that he suffered from glaucoma that led to cataracts. He cites Borges’s judgments on the veracity of other great writers who pondered loss of vision:

Shakespeare, wrote Borges, was not quite accurate in describing the world of the blind as dark: his vision was obscured not by blackness, but by roiling mists of green light. He preferred Milton’s greater subtlety; Milton, who ruined his eyes writing antimonarchist pamphlets and whose “dark world and wide” conveyed the way the blind are obliged to move tentatively, hands outstretched.

Continuing the examination of the head, Francis moves from the eyes to the face. Recall that the faces of the cadavers were covered in my anatomy lab. We largely recognize each other through distinguishing facial features; by shielding this part of the anatomy, the reality that the corpse once was a living person was attenuated. When Francis describes facial structures, he highlights their connection to our sense of mortality:

Advertisement

When I later became a demonstrator of anatomy, one of my jobs was to reveal these muscles in order to help students understand the way that stroke or palsy can affect the face, as well as give a grounding to those who’d one day perform Botox injections, facelifts or facial reconstructive surgery…. Exposing each layer of the face was a process of gradual revelation, journeying from the skin, so reminiscent of life, down to the skull, so emblematic of death.

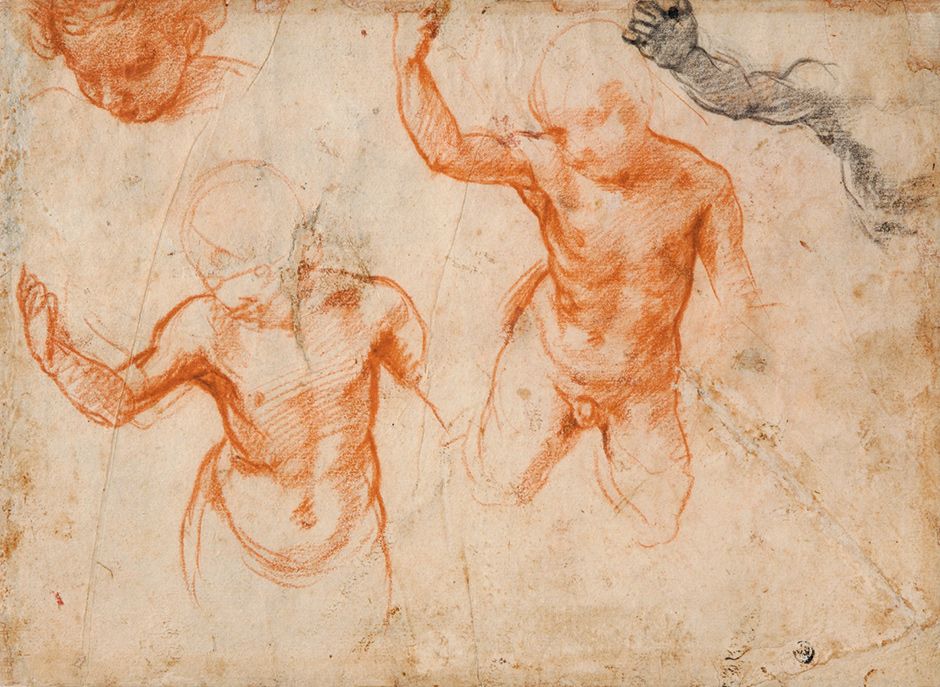

Leonardo da Vinci strove to capture anatomic accuracy in his art, believing that the facial muscles directly communicated with the soul. Francis quotes from his writings about “universal conditions of man,” including joy, sorrow, fear, and boldness, each expressed in distinctive changes in our visage. By studying the actions of facial muscles that represented emotions, da Vinci wanted to draw “close to understanding the divine source of emotions themselves,” Francis writes.

He was not interested in portraying bland representations of beauty: he wanted to capture faces as they are, as they move, whether ugly or beautiful, and if those expressions were extreme—all the better. To anatomize was to come closer to God.

Fondation Custodia, Collection Frits Lugt, Paris

Andrea del Sarto: Studies of a Child, 1522–1526; from the exhibition ‘Andrea del Sarto: The Renaissance Workshop in Action,’ at the Frick Collection, New York City, October 7, 2015–January 10, 2016. The catalog—by Julian Brooks, Denise Allen, and Xavier F. Salomon—is published by Getty Publications.

While I was taught about the body’s structures through analyses largely remote from their associated functions, Francis narrows the distance from the anatomy lab to the clinic. He reflects on how a physician focuses on a patient’s face to obtain clues about not only a diagnosis but the person’s emotional temperature, as well as his own:

When I met people who’d developed frown lines too young, I began to question more about why that might be the case. I tried to distinguish those who were angry or distrustful from those who were simply afraid or feeling vulnerable, those who were anxious from those who were anguished. On meeting someone with an open, delighted face, I began asking about the secret of their happiness. And I realized that when my own expression showed irritation or impatience, relaxing my face made me feel and consult better.

The chapter on the torso and upper limbs unexpectedly brings the reader to Homer; Francis wonders if he might have been a “battlefield medic,” based on his detailed clinical descriptions of war wounds:

The warriors and camp-following poets were familiar with what is now called “major trauma,” and may have developed their own trauma care…. Repeated through The Iliad are careful accounts of spear wounds, arrow strikes and sword blows, which take care not just to describe the part of the body that has been wounded, but the physiological effects of those wounds and, on occasion, specific treatments.

Clinical insights from the Trojan War still apply in modern combat:

When Hector paralyzes Teucer’s arm by hitting him “on the collarbone where it divides the neck from the chest” it’s an accurate description of a trick still used by martial arts experts today—“The Brachial Stun.” A blow to this area may not just temporarily paralyze the arm: if it causes pressure on part of the carotid artery, it can trigger a reflex slowing of the heart. In sensitive individuals the heart can slow to such a degree that the victim falls unconscious. There are innumerable “brachial stuns” available to view on the Internet—home videos of US Marines practicing on one another in their barracks, black belts filmed in the ring, even police officers attacking their suspects. Watching them, I thought of Teucer crumpling to the ground with his numb, lifeless arm.

Homer was not alone in drawing lessons from battle. A careful reading of Hippocrates, Francis notes, reveals not only the famous maxim “First, do no harm,” but also “He who would become a surgeon must first go to war.”

Greek and Roman conflicts are fertile ground from which to explore the clinical outcomes of anatomic injury. But Francis also is intrigued by the metaphysical meanings of wounds described in the Bible. Jacob famously wrestles with an unknown visitor at night, perhaps an angel, perhaps his alter ego. Hurt in the struggle, he limps, and this, the Torah teaches, is why the sinew around the hip should not be eaten.

I always found this a most curious injunction, related to the classification of foods as kosher or not kosher; but here the classification is based on human rather than animal anatomy (e.g., cud, hooves, scales). I learned that Jews are not alone in sanctifying body parts:

The hip can represent the life that as human beings we carry within us. Tibetan Buddhists make trumpets from the bone in order to remind themselves of death, and in the book of Genesis the joint is taken as one of the principal sources of human life. Jacob, grandson of Abraham, fools his brother Esau into forfeiting his inheritance. The two are twins and this isn’t their first fight: earlier in Genesis we’re told that Jacob was born grasping at his brother’s heel (his name Yaakov is related to the Hebrew akev, meaning “heel”).

Drawing on scholarly speculation, Francis wonders whether there is a sexual overtone to Jacob’s wound from his night of wrestling. The exact location of the wound is a matter of speculation:

Rabbis and Hebrew scholars can’t agree on the exact significance of the story. One perspective is that the hip and thigh were, for the ancient Semitic culture of Abraham and Jacob, storehouses of sexual and creative energy. The word in the text, yarech, could refer to the inner curve of the thigh where it folds onto the scrotum in men, and the vulva in women—a Hebrew scholar told me that it is probably better translated as “groin.” The same word is used in the Book of Jonah to describe the inner hollow of a boat, and in Genesis, chapter 24, Abraham asks his servant to swear an oath by touching him in the hollow of the thigh—a reference to the ancient custom of swearing by the testes (hence, “testify”). From this perspective, by touching Jacob’s groin and hip the angel imparted the strength and authority to father a whole nation.

Jacob’s struggle fits within the arc of many stories, a journey of self-discovery where the hero experiences opposition and injury, and ultimately prevails. Such narratives, Francis notes, can echo the experience of illness:

There’s an enduring fascination with Jacob’s struggle because he seems to be wrestling not just with an angel, but also with the frailty and resilience that as human beings we all embody. Some commentators have gone so far as to see in it all the hallmarks of a classic folk tale, in which an individual embarks on a perilous journey, takes on forces that seek to destroy him, is branded by that struggle, but ultimately triumphs. It’s a pattern that mirrors the convalescence stories going on in orthopedic and rehabilitation wards all over the world…

There is currently considerable controversy about what kind of students should be admitted to medical school. Who will become the “best doctors”? Some argue that those with refined senses from studying painting or sculpture or music, or those who have delved deeply into novels that explore character, will be more insightful observers of the patient and his distress. I doubt whether this debate will be, or can be, resolved. Medicine is a highly individual profession, with a spectrum of personalities and interests among its practitioners. It is not a question of whether doctors like Gavin Francis with an artistic and literary sensibility can be proven superior in their clinical acumen compared to those who view the body in strictly scientific terms. But what is certain is that physicians like Francis can make its study more captivating.