When he mailed the first missive to the woman who would become his wife, Vladimir Nabokov was a penurious, Berlin-based poet known to the émigré community as “V. Sirin,” a name that felt more familiar to him than his own. He dreamed still of Russia. When he mailed his last letter, he was a wealthy American novelist living in Switzerland, self-conscious about the quality of his Russian. In between came a shelf of literature, three wrenching changes of country, and nearly fifty years of marriage. It was the longest-running, most intimate correspondence of Nabokov’s life, in part because his wife quickly came to handle most others. Her husband had, she explained to William Maxwell when he phoned in 1964 on New Yorker business, a “communicatory neurosis.”

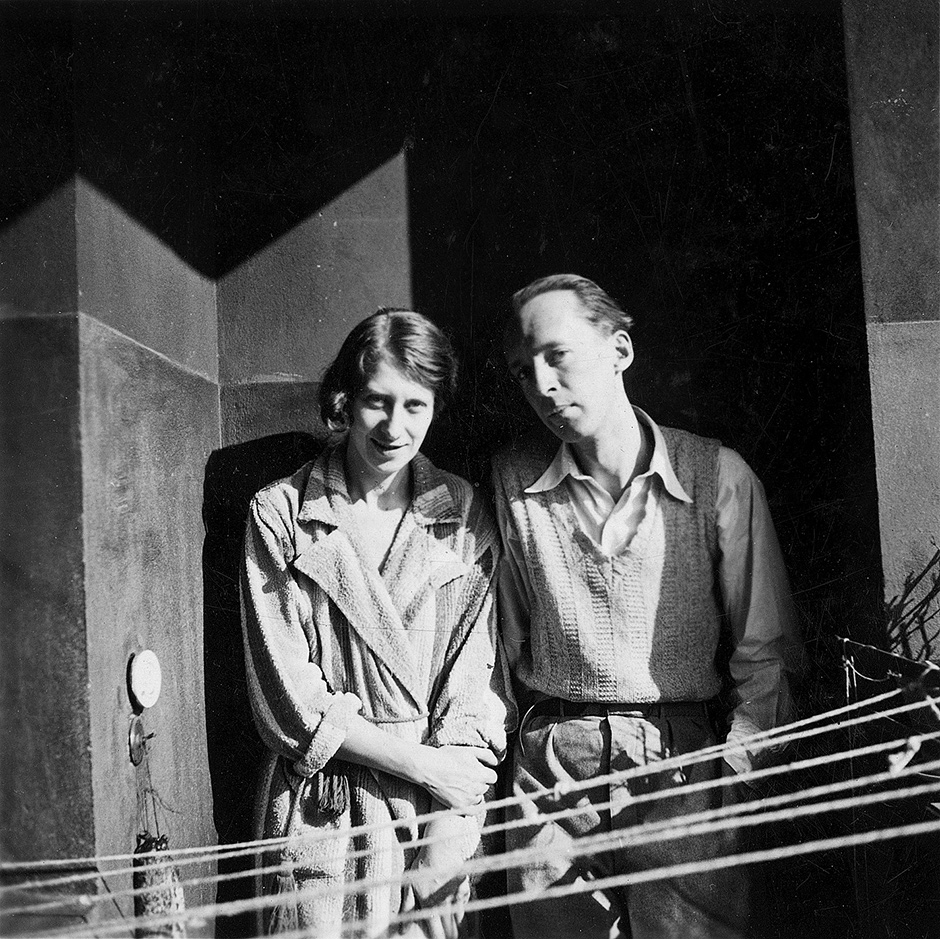

She molted too, from the fictional Mme Bertran, a code name she assumed in Berlin to disguise herself from Nabokov’s family, to the marble, monumental Véra Nabokov of Montreux. Both had been “perfectly normal trilingual children” in St. Petersburg, where their paths crossed but never intersected. When finally they met, in their early twenties, in Germany, Nabokov believed destiny had arranged the encounter. Their union felt to him preordained, a point he made by summoning an image from The Count of Monte Cristo. He mangled it a bit; he generally felt himself beyond language, illiterate, clumsy on the page when it came to Véra Evseevna Slonim. “I can’t tell you anything in words,” wailed the greatest prose stylist of the twentieth century. He knew a fairy tale when he saw one. He was a man deeply in love.

Enchanted by Véra’s lightness, laugh, and “unique charm,” her “stretchy vowels,” “sweet long legs,” and “little dachshund paws”—he did not mention the pages of his verse that she had committed to memory—he poured out his heart. He needed her desperately. He could not write a word without hearing it in her pronunciation. He could not wait for her to read his pages. She understood his every comma. “All the happiness of the world, the riches, power and adventures, all the promises of religions, all the enchantment of nature and even human fame” could not equal, he swore in 1925, two of her letters.

Very quickly she began to color his writing. A pleasure of any extended collection of correspondence lies in the savory anticipations; we read for the shimmer of the future, to which we alone are privy. Vladimir and Véra had known each other for seven months when he invited her to move to America with him. He could offer “a sunny, simple happiness—and not an altogether common one,” a promise on which he largely delivered. “Your father,” he informed her in 1926, a year after their marriage, “finds that I ‘specialize in risqué subjects.’” All would happen precisely as the couple envisioned, if not remotely on schedule.

And Nabokov found the means to express the “cirrus-cumulus sensations” that would produce what he always referred to, needed to think of as, a cloudless marriage. Within months of their 1923 meeting, Véra was his joy, his life, his music, his love. She was also his kittykin, his poochums, his mousikins, goosikins, monkeykins, sparrowling, kidlet—since he was not keeping a list he feared he might be repeating himself (he was); he worried he would run out of critters (he did not)—his skunky, his bird of paradise, his mothling, kitty-cat, roosterkin, mousie, tigercubkin.

Through the 1920s he wrote to her of his admiration for Madame Bovary, of the color of snow, of Lenin’s death, about that quack Freud, the half-eaten chocolate in his hand, Longfellow, the yapping of a dog with a tail like a French horn, the rasp of his palm on his unshaved face (it sounded like a car braking), about—it was Nabokov in a nutshell—his fear of the post office, the etymology of the word “tennis,” the “thunderstormy tension that’s the harbinger of a poem.” He omitted no detail of his ablutions, his tailoring, his tennis game, his diet (there would appear to be an unheralded link between cold cuts and literary genius), in part because she made it easy for him to do so. Before a 1926 separation, Véra supplied her husband with a block of dated pages. “My darling,” he reminded her near the end of the first month apart, as he faithfully and exuberantly worked his way through the notepad, “I am the only Russian émigré in Berlin who writes to his wife every day.”

He was needling her. As if gathering her strength for the lifetime of paperwork ahead, Véra proved a disappointing correspondent. “Don’t you find our conversation somewhat…one-sided?” Nabokov wondered in 1924. He had been tempted to mail her a blank sheet of paper with a question mark in the middle but hated to waste the stamp. “My beloved insecticle,” he reminded his wife two years later, “today, by my count, I’m writing my hundredth page to you. And yours will make up no more than ten or so. Is this amiable?” He estimated that he had generated 80 percent of their correspondence. “You write disgustingly rarely to me,” he observed, sounding what was to become a half-century-long refrain.

Advertisement

In the end all of the correspondence would be his. Somewhere along the line, Véra’s letters disappeared. Dmitri Nabokov maintained that his mother—pathologically private, and well aware who the writer in the household was—destroyed them, although there is no evidence that she did so. It is just as likely that their recipient misplaced them; he was a man in whose hands telephone numbers evaporated, who could lose a book of matches in a tiny room, who might entrust his return ticket to the train conductor. We are left to reconstruct the object of Nabokov’s affection entirely from his side of the correspondence.

For all his sense of predestination—for all the rivers waiting for Véra’s reflection, the roads for her steps—theirs was not a marriage of similar minds. He effuses; he swoons; he levitates. She tugs him a little back to earth. He concocts a plan for the two of them to escape for a spell to Biarritz; his “long bird of paradise with the precious tail” does not think visas or funds will allow it. “Try not to look at this as if it were myth,” Vladimir rebukes Véra, a year into their marriage, although he is himself unable to crack the thorny riddle: “How can we get 500 marks?”

For the most part he appreciates her “silly, practical thoughts” and indulges her moods. “Try to be cheery when I come back,” he begged in 1942 from wintertime St. Paul, “(but I love you when you’re low, too).” He is cross with her only when she describes a butterfly as “yellow.” “There are,” rails the man who would hold that he often reproduced Véra’s picture “by some mysterious means of reflected color in the inner mirrors of my books,” who splashed prisms across the page, “a million shades of yellow.”

For once happiness writes in iridescent color. Togetherness does not; it is an irony of the Nabokovs’ lives that we owe most of their correspondence to financial hardship. After Hurricane Lolita swept through in 1958, delivering them from all such concerns, we have, properly speaking, only eight letters. The earlier gems for the most part date from the trip Nabokov took as a farmhand shortly after the two met; to his 1925 turn as a traveling companion; to the 1942 proto-Pnin circuit of the American South, as a lecturer, when he was still shaking off the urge to write in Russian, when briefly he allows himself to mourn his loss, having traded his mother tongue for a language that “is an illusion and an ersatz.”

In 1936 and 1937 Nabokov traveled to Paris, to which most of the Russian émigré community had then gravitated. The idea was to cultivate literary contacts, deliver some paid readings, ultimately to remove his family from Hitler’s Germany. (By that point they were a family of three, Dmitri having been born, silently in these pages, in the spring of 1934.) Nabokov had been plotting a Parisian move since late 1932. “We will rewrite Despair,” he promised Véra, “and in January we will move here.” The translation was made. The move was not.

Four years later, with a greater sense of urgency, he returned to France. Véra remained his angel and his enchantment but the quotidian asphyxiates the endearments. Might she file the papers for an American copyright? What should he talk about with a British editor? Should he buy a butterfly net? Which of the Russian works should he translate next? He tried out some lines and submitted embryonic ideas, along with pleas for razor blades. From La Rotonde, a coffee at his elbow, he reported that he was the toast of Russian Paris. On the one hand, he floated in “a syrup of compliments.” On the other, he railed against the “concentric whirlwinds” in which he lived. “I was absolutely not made for the colourful life here,” he griped, the more so as it left him without the ballast of his writing hours. To save money he accepted all dinner invitations. (He is not as superior as he will sound in Speak, Memory. The morbid dislike of Parisian restaurants would come later.) The letters are studded with proper names; he seems to have visited with the entire emigration.

Advertisement

And he missed his wife. He was “furiously bored,” miserable, enervated without her. He had no one to whom he could complain. By April, after eleven weeks apart, the separation had become a torture. He could endure it no longer: “Without the air which comes from you I can neither think nor write,” Nabokov grumbled. In the same letter he admitted that he had shared passages of her recent letter with two friends. “They said they understood now who writes my books for me,” he added. He hoped she was flattered.

The Berlin-bound reports—Véra later claimed her husband wrote her daily if not twice a day in 1937, although the evidence here suggests he did so several times a week—could hardly have been more illuminating. They also obscured, like windshield wipers hauling snow in one direction to smear slush in the other. Nabokov dreamed of Véra; he walked about “in a sort of cloud of tenderness” toward her; he loved her beyond words. He shared every detail of his existence save—Find What the Husband Has Hidden—for one.

Véra had her suspicions. As from different cities the couple plotted their German exit, she balked and stalled. If he said France, she said Italy. She hatched a sudden plan to visit his mother in Czechoslovakia. The arrangements were complicated by the couple’s statelessness; he ran about attempting to arrange the necessary paperwork. It was diabolical. If, as Nabokov observed in Speak, Memory, documentation constituted “a Russian’s placenta,” he was thrice-born. “The more I think about it and consult with others the more ridiculous your plans seems,” he scolded in March 1937.

If she had listened to him, he chided two weeks later, they would already be sitting in the south of France. He had only been accurate and precise. Why, he demanded, “these repeated and pointless confusions”? Their correspondence had devolved into a series of petty bureaucratic reports, he noted, adding that he adored her all the same and that the delay drove him crazy. He conceded defeat at the end of April; he no longer had the strength to continue their “long-distance chess game.” For the first and only time the Nabokovs spent May 8—the anniversary of the day they had met—apart.

As Nabokov would later say of Sirin’s sentences, there was something “clear but weirdly misleading” about the 1937 correspondence. While floating in a cloud of tenderness for his wife, Nabokov had since February been walking about in the “delicious daze of adultery.” As he assured Véra that he loved her beyond words, he was assuring her rival that he loved her more than anything on earth. He would deny the affair in Prague, where the couple were reunited in May, and from which he continued to post anguished letters to his lover. He would admit to it only weeks later in the south of France, as he continued the extramarital correspondence. He could not live without his new love; he had never known such longing. At the same time, he could not extricate himself from the marriage. It made for a miserable summer. From it came The Gift, Nabokov’s last novel in Russian and in his estimation his best, a novel that has been described as his ode to fidelity. By far the most appealing woman in his fiction, its heroine in nearly all ways resembles Véra.

In his diary we expect to meet a writer in his rhetorical all-together. In his correspondence he assumes a persona, though not so much of a disguise that we fail to recognize him; the letters are more like CAT scans than biopsies. We read them less for the tingle down the spine than to glimpse where the writer and his ideas came from, to learn what they cost him, for the yearnings and misgivings, the false starts and the familiar sparks. How does the Nabokov of Letters to Véra compare to the Nabokov of Speak, Memory or of the 1989 Selected Letters, a volume in which many of the greatest hits here appear?

He is as ever allergic to pomposity, pretension, vulgarity, though not above sharing a dirty joke. He is either socially inept or he artfully masquerades as such. (“I feel myself a cretin in cunning human connections,” he would claim in 1939; two decades letter, he was socially “a cripple.”) Already he blasted mediocrities like Stendhal. He is a good gossip. He sounds unmistakably like himself, if without the polish, the mandarin disdain, the stage-managing. The jewels skitter helter-skelter across the page, from an émigré’s “stoop-shouldered speech” to a 3:00 AM encounter with a “very hungry, very lonely, very professional mosquito,” to a “waiter sweating hailstones,” the precursor to the broken-down deodorant under the arms of exam-tackling Cornellians. He rarely misses the “dimple of sunshine on the cheek of the day.” Already in 1939 he has enunciated the theory that would inform so much of the literature: second readings alone counted.

An exile, goes the saying, is a refugee with a library; Nabokov was an exile with a dictionary. (His New Yorker editor assumed he had learned his English directly from the OED.) Naturally there is less pedantry and more tenderness in the correspondence with Véra, but the strong opinions and lacquered images are in place well before the Russian poet dashed into the phone booth to emerge as an American novelist. There are surprises along the way. For a man thrice ambushed by history, Nabokov evinced surprisingly little interest in current affairs. He enjoys music on occasion and once even (flagpole, fetish) defers to Freud. At one point he contemplates a lecture on women writers. It was in part thanks to Irène Némirovsky, then a well-established novelist, that Grasset published Laughter in the Dark. The New Yorker rejected his poem on Superman and Lois Lane’s honeymoon night.

Superimposing his magic carpet patterns upon each other from a young age, he is a man exquisitely attuned to anniversaries. He will ultimately develop an elegiac streak but more often tended to project his nostalgia into the future: in 1941 he cites a line about his linguistic travails from the “2074, Moscow” edition of “Vladimir Sirin and His Time.” He is delighted in the 1930s to read that he has been ranked among “the small number of world humourists.” Never, he purrs, has a truer thing been written about him. Sometimes the humor was inadvertent. In 1944 he wrote to Véra: “I am sending you, my darling, two bills, which evidently need to be paid.”

Letters to Véra goes silent from 1954 to 1964, the years that make for the longest section of Selected Letters and that would return the couple to Europe. In Nabokov in America, Robert Roper revisits the decades that precede that second “voluntary exile.” Even the most ardent admirer of The Gift has to admit that the central panel of the Nabokovian triptych—the years that yielded what Roper calls “the luminous books of his American prime”—is the dazzler. He follows the couple across America, retracing their butterfly-collecting excursions over several thousand miles. He sets himself a twofold mission: he means to prove Nabokov very much an American. And he hopes to say simpler, less esoteric things about the novelist, to liberate him from the grasp of the academy, a mission that would have amused his subject. Nabokov could not have guessed himself in need of rescue, least of all from a group that had had little use for him—at one point his Wellesley title was the extraterrestrial-sounding “Interdepartmental Visitor”—in the first place.

Roper writes with loping energy and a passionate, longtime love of the literature; his are a fan’s notes. He trails the couple across the American West as Speak, Memory flops commercially, as Nabokov tends to that other novel, that “great and coily thing,” as he described it, the shocking work that Véra’s father had unknowingly anticipated decades earlier. Roper juxtaposes the nymphet’s childhood with Dmitri’s, of which Lolita’s is the “dark negation.” He veers a bit into the thicket in search of her origins, suggesting a parallel with Absalom, Absalom!, another monomaniacal volume, if one he acknowledges that Nabokov nowhere mentions and surely never read. At times Roper whips himself into a froth; his is more a convoluted than a fancy prose style. Here he is on the approach of Hurricane Lolita:

The Nabokovs were as solid and well prepared for big change as can be imagined; they were deeply in love, partners in an enterprise—the advancement of the husband’s writings—that seems never to have awakened envy in the wife; neither had a drinking problem or at this point was prone to stray; and the husband’s oft-expressed belief in his own genius, which once might have hinted at underlying uncertainty, the recognition that the best creators are often plowed under regardless, graced only with the world’s forgetting, had, like Vladimir himself, only grown stouter.

How you feel about his work may depend on how interested you are in roadside American architecture of the 1930s or in Dmitri’s mountaineering instructors. It may also depend on how much you are willing to believe that Nabokov was steeped in or influenced by American fiction, much of which even Roper concedes Nabokov did not know; he points out that—with the exception of The Headless Horseman—Nabokov was on his arrival in 1940 largely ignorant of non-European, non-Russian literature. Astutely, he suggests that on occasion a fat debt lurks in the derision. Indeed Nabokov could seem to protest too much. Might a certain admiration for D.H. Lawrence, Roper wonders, explain the “ostentatious sneer”? He argues convincingly that America emboldened Nabokov and worked as an accelerant on his pyrotechnics, intensifying Lolita’s pastel prototype. On his 1939 short story “The Enchanter,” this country performed the kind of giddy supersizing magic that conjures a Coupe de Ville from a Deux Chevaux.

Roper aims to prove that a “wide-ranging and semi-surreptitious immersion in American cultural materials, his assimilating of our literary traditions” shaped Nabokov’s work. The first case comes more easily than the second. Somehow Roper has Nabokov taking his place among Kerouac, Faulkner, Mailer, sharing the page with John Muir, Thoreau, Lewis and Clark. It is not unfair to compare his career with that of Ayn Rand, but I would not want to be around when Nabokov heard Lolita’s gestation discussed in even remote proximity to that other newly minted American, Thomas Mann, whose work he reviled.

Indeed he admired Salinger. Indeed the two men’s work appeared, at the same time, in the same magazine pages. But are Lolita and The Catcher in the Rye truly “vaguely aware” of each other? Is Humbert really meant to parody Holden? Roper compares scenes in the two novels—Holden observes Phoebe in her open-mouthed slumber, as Humbert gazes on the sleep-talking Lo—to conclude that Nabokov imbibed Salinger’s vapors. “In its essence,” argues Roper, Lolita evokes Moby-Dick, “which Nabokov might never have read to the end.” Why? Because the two share “an immense anxiety about the world,” and in their ways, because both novels allude to Shakespeare. He goes out on multiple limbs, occasionally sawing them off behind him. Having speculated that Nabokov may have known The Last of the Mohicans, he concludes: “Probably Nabokov’s path to channelling this mode is best explained, however, not by examining literary influences but by invoking the imponderables of inspiration.”

It is a little easier to discern shades of Wordsworth and Whitman in Pale Fire. But generally it is dangerous to play the Kevin Bacon game with Nabokov, to separate him even by six degrees from Dickinson, Emerson, Hawthorne. The overly inferential critic risks a Kinbotean crash against the windowpane. Nabokov took from America what he needed—the kitsch, the candor, the materialism—and left the rest. The country’s natives never ceased to amaze: they planted Bibles in hotel rooms, shared combs, and taught German literature without mention of Kafka. He was radical on the page as only a man in love with prerevolutionary Russian orthography can be. Yes, he believed himself an American writer. He felt he had done his best work in English; his debt to this country was unspeakably great, his patriotism unshakable. Any insult to the Stars and Stripes left him howling.

Even if he exaggerated in claiming that Lolita was without “precedent in literature,” that Pnin had no fictional antecedents, that Pale Fire resembled nothing that had been written before, that no author had ever attempted what he had done with “The Vane Sisters,” the aristo-aesthete with magnificent disdain for convention had a point. He had slipped his bonds so many times he could no longer be pinned down. He remains beyond classification, though he may share a genus with another exile who reinvented a nonnative language while rewriting the map. “Vous êtes Anglais?” a French journalist asked Samuel Beckett. “Au contraire,” replied the Irishman. That Wellesley title said it all. Interdepartmental visitor indeed.

This Issue

November 19, 2015

A Conversation in Iowa—II

The Man Who Flew Like a Bird