We needed a reactionary to defend our painting, which Salon-goers said was revolutionary. Here was one person, at least, who was unlikely to be shot as a Communard!

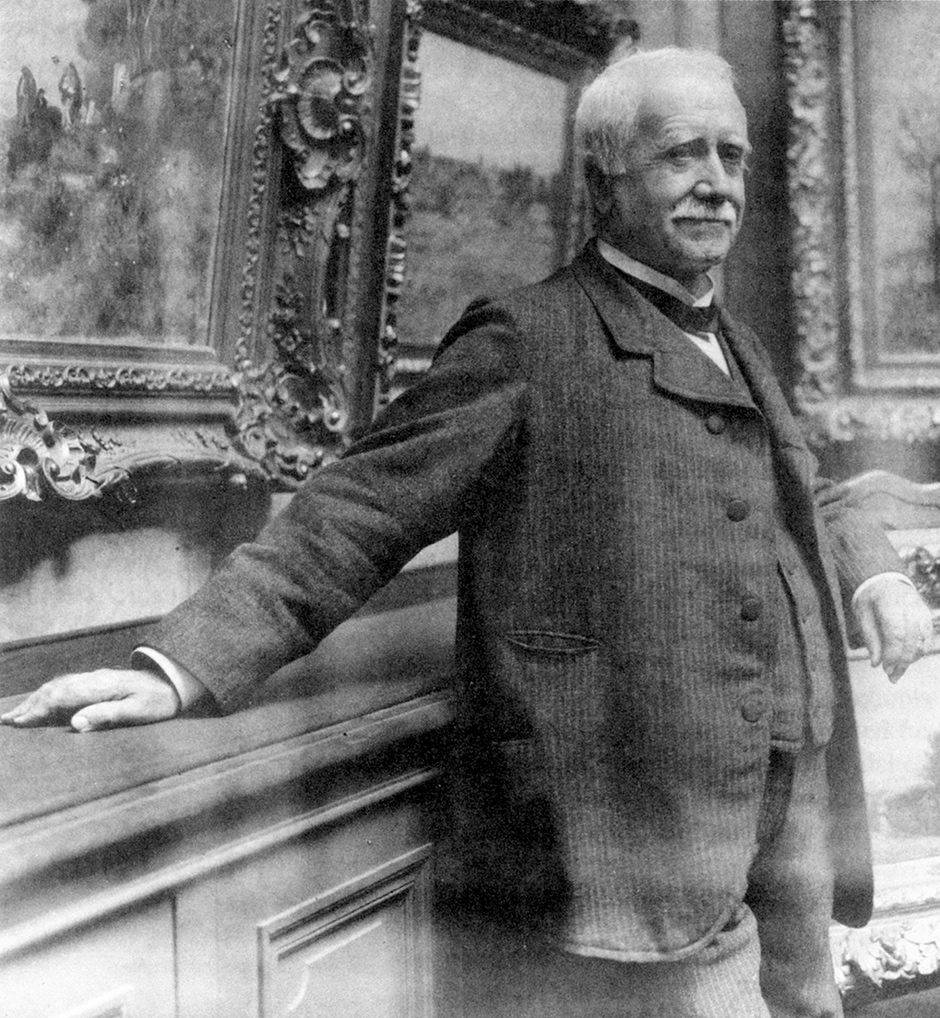

Renoir’s remark—as well as his affectionate portrait, painted in 1910—introduces Paul Durand-Ruel as the least likely champion of avant-garde French painting in the second half of the nineteenth century. “Seeing him in his eternal frock coat,” observed Le Guide de l’amateur d’oeuvres d’art in 1892, “you would take him for a provincial notary or a lawyer from the suburbs: punctual, methodical, and formal.” In 1943, John Rewald, a leading scholar of Impressionism, wrote, “No name of a non-artist is more closely bound up with the history of Impressionism.” While Monet, Renoir, Degas, and Pissarro are indeed household names today, Durand-Ruel remains familiar only to specialists.1

“Inventing Impressionism: Paul Durand-Ruel and the Modern Art Market”—a splendid exhibition in Paris, London, and Philadelphia this year—rehabilitated the Parisian dealer who mounted the first show of the group’s work in New York in April 1886, where he soon opened his first gallery. He organized London’s first blockbuster exhibition of 315 Impressionist paintings in the Grafton Galleries in January 1905. The recent exhibition and catalog are accompanied by a new edition of Durand-Ruel’s Memoirs, written in 1911, and translated into English for the first time. Both the catalog and Memoirs draw extensively on the vast, miraculously intact Durand-Ruel archive, still held by descendants of his family.

Paul-Marie-Joseph Durand-Ruel (1831–1922) was a devout Catholic who attended mass every day and an ardent monarchist who advertised his support for the Bourbon pretender to the throne in October 1873. His sons were educated at the new Jesuit school of Saint-Ignace on the rue de Madrid; his daughters at the Couvent de Roule on the Avenue Hoche, founded in 1820. Bitterly opposed to the Third Republic’s secular education policy, Durand-Ruel was arrested in 1880 for protesting the government’s suppression of the male religious orders. (“It was important that all my children received not just a good education but also a Christian upbringing that concurred with the way I and my entire family felt.”)

Edmond de Goncourt, who visited his vast apartment on the rue de Rome in June 1892, was struck by the crucifix affixed to the head of his bed. It is also likely that Durand-Ruel shared the virulent anti-Dreyfusard sentiments of Degas and Renoir, although his ultra-conservative opinions did not prevent him from establishing close (and enduring) professional relations with the ardent republican Monet or the anarchist sympathizer Pissarro.

The only son of a clerk in an art supplies store, he married the proprietor’s daughter and gradually transformed her family’s business into an elegant gallery on the rue de la Paix that specialized in modern art. (His father became the principal dealer in the work of William Adolphe Bouguereau between 1855 and 1865.)

Late in life, Paul Durand-Ruel confided to the critic Félix Fénéon that he “detested business and dreamt only of becoming an army officer or a missionary.” He had passed the entrance exams for Saint-Cyr, the French military academy, in October 1851, was accepted into the 20th light-infantry regiment, but seems to have had a change of heart when required to sign up for seven years. Instead he went to work selling art. He had, he later said, an intense experience when he saw the thirty-five paintings by Eugène Delacroix on view at the Exposition Universelle in 1855. He wrote in his memoirs that he was suddenly struck by “the triumph of modern art over academic art.”

He first acted as an expert—the dealer on hand and ready to answer questions—at a sale of modern paintings in April 1863, at which a critic for the Chronique des Arts described him as “a most affable and attentive young man.” Affability remained one of his defining qualities, as the art critic Arsène Alexandre discovered when he interviewed the eighty-year-old Durand-Ruel for the German literary magazine Pan in 1911. But as Alexandre also noted, mild manners and courtesy masked “an unshakeable obstinacy, an iron will, though not a violent one, that achieves its ends with a smile.”

Like his father, Paul Durand-Ruel was, aside from Delacroix, initially drawn to the Romantics and the Barbizon painters, to whom he referred as “la belle école de 1830”: these included the landscapists Camille Corot, Théodore Rousseau, Narcisse Diaz, Jules Dupré, and Charles Daubigny; and the “realists” Jean-François Millet and Gustave Courbet, painters of “nature,” including human and animal figures.

Between 1866 and 1872 he and his business partner, Hector Brame, a former actor, sought to establish a monopoly of these artists’ production by paying high prices for their paintings. Durand-Ruel and Brame purchased a group of ninety-one works by Rousseau in 1867, six months before his death, for 100,000 francs. They offered Millet an annual salary of 30,000 francs in 1866 in return for an exclusive contract (which the artist declined) and in 1872 spent nearly 400,000 francs on his pictures. Between April 1872 and February 1873 the ultra-monarchist Durand-Ruel bought, for over 94,000 francs, fifty-two paintings by the former Communard Courbet, who remained in exile following his imprisonment for the destruction of the Vendôme Column. In July 1872 he acquired Courbet’s notorious Return from the Fair (1863; whereabouts unknown, presumed destroyed)—a monumental canvas, rejected even from the Salon des Refusés of that year for its rampant anticlericalism. (It showed a group of drunken clerics making their way home after one of their weekly lunches.) Durand-Ruel paid 10,000 francs for the picture, and sold it the next day for a profit of 50 percent.

Advertisement

Durand-Ruel was also avid for the work of younger artists, including returning Prix de Rome winners whom he visited in their studios, and emerging Salon painters whose reputations remained to be established. He was an early patron of Léon Bonnat (1833–1922), whose Neapolitan Peasants in Front of the Palazzo Farnese he acquired at the Salon of 1866 for 10,000 francs.2 He paid even more—16,000 francs—for the twenty-seven-year-old Henri Regnault’s life-sized Salomé (Metropolitan Museum of Art), one of the sensations of the Salon of 1870. For comparison, it is worth recalling that Manet’s Olympia of 1863 (Musée d’Orsay), the scandal of the Salon of 1865 and unsold during the artist’s lifetime, was withdrawn from his estate sale of February 1884 when it failed to reach its reserve of 10,000 francs.3

During the 1860s, Manet and his “school” had made not the slightest impression on this rising dealer of modern art. It was only after the family’s flight from Paris during the Franco-Prussian War, when Durand-Ruel installed his wife and five children in the Périgord and boarded the last train to London on September 8, 1870 (taking his pictures with him), that he met the expatriate artists Monet and Pissarro. In 1871 he acquired work by them for very modest sums: two hundred francs for Pissarro’s landscapes, three hundred francs for Monet’s.

Following Durand-Ruel’s return to Paris at the end of September 1871, in November his wife, Eva Lafon, pregnant with their sixth child, died of an embolism. Following this tragedy, in January 1872 he was introduced to Manet’s painting by the Belgian artist Alfred Stevens, from whom he acquired Moonlight at the Port of Boulogne (1868; Musée d’Orsay) and The Salmon (1869; Shelburne Museum). “I frankly admit that up to that point I had never seriously looked at Manet’s work,” Durand-Ruel recalled forty years later. “Dazzled by my purchase—because you never truly appreciate a work of art unless you own it and live with it—the very next day I went to Manet’s and bought, on the spot, everything I found there.”

As he had done with the previous generation of artists, Durand-Ruel attempted to establish retroactively a monopoly of Manet’s work. It was also in 1872 that he made his first purchases of landscapes by Renoir and Sisley, flower paintings by Fantin-Latour, and ballet scenes by Degas. In keeping with the official hierarchy of genres observed in the Paris art world—despised by the dealer and the Impressionists alike—paintings of subjects such as Degas’s dancers sold for far higher sums than landscapes or still lifes. In January 1872, Durand-Ruel paid Degas 1,500 francs for The Ballet from “Robert le Diable” (1871; Metropolitan Museum of Art). For Renoir’s early masterpiece The Pont des Arts (1867; Norton Simon Museum)—his first purchase from the artist, in March of that year—he paid only two hundred francs.4

Still, during the 1870s Durand-Ruel had only a marginal part in the emergence of Impressionism and the New Painting; he remained committed above all to the aging Barbizon painters and the belle école of 1830. In fact, it was not until the 1890s that prices for Impressionist painting would rise to the level of mainstream contemporary French art. In the 1870s Durand-Ruel overextended the firm, opened branches in London and Brussels (which he was forced to close in 1875), acquired collections that would be auctioned under their proprietor’s names with guarantees far beyond the actual bids, and established limited stock partnerships with investors who lost half their capital. Such strategies are familiar in today’s overheated market for contemporary art.

Furthermore, Durand-Ruel was burdened by debt, having borrowed at usurious rates since 1869. Thus, after fairly modest acquisitions of the New Painting, between 1875 and 1880 he stopped buying new work directly from any of the Impressionists altogether. He lent only two paintings by Sisley to the first Impressionist exhibition, held at Nadar’s photography studio in April 1874,5 although he bought, very cheaply, eighteen pictures at the first (and disastrous) Impressionist auction in 1875. He rented—rather than donated—three rooms of his premises to the Impressionists for their second exhibition in March 18766; and in February 1877 he sublet his galleries to an upholstery business to cover expenses. By April 1879 he had been reduced to a single office on the rue Saint-Georges, not far from Renoir’s modest apartment. Courbet, to whom he still owed much money, assumed that Durand-Ruel had declared bankruptcy.

Advertisement

The dealer’s fortunes revived only in the winter of 1880 after an infusion of capital from Jules Feder, director of the Union Générale Bank founded in Lyons in 1875 by Catholic monarchists and reestablished in October 1878 under the ownership of Paul Eugène Bontoux, former chef de service at the Banque Rothschild. In December 1880 Durand-Ruel resumed purchasing from Boudin, Pissarro, and Sisley, insisting that he represent them exclusively. “You cannot imagine how happy I am,” Pissarro informed a niece in January 1881.

Durand-Ruel, one of the great Parisian dealers, came to see me and has taken a large number of my paintings and watercolors. He has proposed to take whatever I paint. This offers me tranquility for the foreseeable future, and the means to make important work.

Similar agreements with Monet and Renoir followed, allowing the latter to travel abroad for the first time in his life.7 An embittered Gauguin noted in the summer of 1881 that “at the rate that Durand-Ruel is going with Sisley and Monet, who are steaming away with their pictures, he will soon have four hundred that he will not be able to get rid of.”

Despite this replenishing of his stock of Impressionist paintings, Durand-Ruel’s recovery was short-lived. In January 1882 the Union Générale Bank suspended payments to many people from whom it had borrowed money. This led to the collapse of the stock exchange and the sentencing of Feder and Bontoux to five years in prison. Durand-Ruel was obliged to sublet his premises yet again—this time to the Banque de Paris—and the financial crisis inaugurated, as he put it in his memoirs, “another four or five dreadful years” for his business.

But by then his commitment to the Impressionists was unquestioned, if still not profitable. In March 1882 he was the major contributor to the seventh Impressionist group exhibition on the rue Saint-Honoré, with the large number of works on display by Pissarro, Monet, Sisley, and Renoir all belonging to him.8 The artists themselves were by now skeptical of such undertakings. Pissarro had to convince Monet to participate: “For Durand and even for us, this exhibition is a necessity.”

Renoir, recovering from pneumonia in L’Estaque, was determined to boycott such group shows in favor of the official Salon but reluctantly conceded that Durand-Ruel was free to exhibit paintings from his own holdings: “You may include any canvases in your possession without my authorization; they belong to you.” Toward the end of the year, Durand-Ruel refurbished a spacious mezzanine apartment on the Boulevard de la Madeleine, in preparation for five shows to be devoted to Boudin, Monet, Renoir, Pissarro, and Sisley respectively between February and June 1883. As the historian Sylvie Patry has pointed out, this series of mid-career retrospectives took place when Durand-Ruel himself had little money, and long after his financial backing had disappeared.

Durand-Ruel was willing to take large risks and marketing Impressionism remained a risky business throughout the 1880s. Embroiled in an ugly dispute over the sale of a forged Daubigny, in November 1885 he justified his actions in the press, ending with an uncharacteristically emotional defense of his support of the New Painting:

Now I come to my great crime, the one that looms above the others. I have long been buying, and holding in great esteem, works by highly original and skilful painters, several of whom are geniuses…. I feel that works by Degas, Puvis de Chavannes, Monet, Renoir, Pissarro, and Sisley are worthy of the finest collections. Already many collectors are beginning to agree, though not all share my opinion.

Perhaps Durand-Ruel’s greatest coup was to organize the first group show in New York—“Works in Oil and Pastel by the Impressionists of Paris”—which opened on April 10, 1886, at the American Art Association at 6 East 23rd Street and then moved uptown to the National Academy of Design the following month. This was the result of intense planning and lobbying. In the summer of 1885 Durand-Ruel had accepted an invitation from James F. Sutton—head of the recently incorporated American Art Association and son-in-law of the founder of Macy’s department store—to exhibit 289 paintings and pastels in New York. Crucially, Sutton arranged for the “duty-free importation of pictures and objets d’art to be shown in its galleries,” and paid Durand-Ruel’s transport and insurance costs. Import duty at 30 percent would be paid on any art that was sold.

Predictably, most of the Impressionists were skeptical. Monet confided his “regret” to the dealer at seeing “certain of these pictures…sent to the land of the Yankees.” Renoir was of similar mind: “I can assure you that I am far from believing in America as the solution.” Nevertheless, on March 25, 1886, Durand-Ruel arrived in New York accompanied by his twenty-one-year-old son Charles and forty-three cases of paintings and pastels valued at $81,799. (Between 1886 and 1898 Durand-Ruel would visit New York nine times.) The exhibition opened in the second week of April, a month before wealthy New Yorkers left the city for the summer, and was deemed a relative commercial and critical success, with forty-nine paintings selling for an estimated $40,000.

Returning from New York in mid-July, Durand-Ruel was already determined to repeat the experience. “Don’t take the Americans for savages,” he told Fantin-Latour, whom he was encouraging to participate in his next exhibition: “On the contrary, they are less ignorant and less hidebound than our French collectors. Paintings that took twenty years to gain acceptance in Paris met with great success there.”

In the end, organizing the second Impressionist show in New York foundered on the resistance of the city’s own art dealers, who protested the duty-free importation of works of art. Nearly three hundred paintings, sent across the Atlantic in October 1886, remained in customs until an arrangement was reached whereby Durand-Ruel was allowed exemption on works that did not belong to him but was obliged to pay import duties on those that did. As a result, the exhibition of 223 “Celebrated Paintings by Great French Masters” did not open at the National Academy of Design until May 25, 1887, “much too late to do business,” he recalled bitterly many years later. This imbroglio convinced Durand-Ruel to establish a permanent gallery in New York and to keep a portion of his stock there. During the next decade, the firm also did business with galleries in the principal East Coast cities, as well as Chicago and Pittsburgh.9

By the mid-1880s, some of the leading American collectors had been regularly coming to Paris to buy modern painting: “l’arrivage des Américains” in May was part of the annual season. In L’Oeuvre, his novel about the art world published in 1886, Zola created the character of the ruthless and glamorous Naudet, “a dealer who for some years had revolutionized the business of selling pictures” and is interested above all in satisfying his American clients. Naudet “waited for May and the arrival of those American art lovers to whom he sold works for 50,000 francs that he had purchased for 10,000 francs.”

In preparing L’Oeuvre during the spring of 1885, Zola had been helped by the painter Antoine Guillemet (1843–1918), who had modeled for Manet in Le Balcon (1868; Musée d’Orsay) and who now provided short essays on a number of dealers, Durand-Ruel included. While competitors such as Georges Petit and Charles Sedelmeyer had already established extremely profitable relationships with visiting American collectors, Durand-Ruel had been unable to do so—according to Guillemet—because of his “obsession with the Impressionists.”10

He is crazy for Monet, persists in buying his work in the hope that he will sell it one day…. He puts all his money and all the money that he can find into justifying this conviction…. He is a black hole for all the sketches that Monet offers him. And Monet angry at Pissarro, Sisley and the others, complaining “Would that I were the only one!”11

With Impressionism still a marginal and contested movement, it was Durand-Ruel’s originality—and genius—to risk exporting blockbuster-scale shows to New York and establishing a permanent presence in the city.

Like Zola’s Naudet, who puts the painter Fargerolles under contract and insists that “from now on, you will work only for me,” Durand-Ruel expected the Impressionists to continue to accept his exclusive representation of them—a matter of moral, rather than legal, contracts. Despite the precariousness of the market for Impressionist painting, Monet, Pissarro, and Sisley each resisted such a monopoly, going so far as to “revoke” their agreements with him in December 1885. As late as 1892, Durand-Ruel was still insisting upon this type of arrangement. To Pissarro, from whom he had just purchased forty-two paintings, he pleaded:

Only with the monopoly that I am requesting from you can I successfully campaign—and that is how the value of pictures is always established…. It is only because I hold all Renoir’s paintings that I have finally managed to get him to the rank he deserves…. I need your promise not to sell to other dealers, even at higher prices.

Having established the markets for the Impressionists in Europe and the US—both by private buyers and museums (the latter only after the greatest resistance)—Durand-Ruel was increasingly disappointed by artists who would not grant him a monopoly. He was also by now an extremely rich man. After hearing him complain about never having made any money in selling pictures, Renoir is said to have shot back—“And how did you make your money? I don’t know of any other business that you have.”

The editors of Durand-Ruel’s Memoirs estimate that he acquired over 12,000 paintings during a fifty-year career, including approximately 1,500 paintings by Renoir, one thousand by Monet, eight hundred by Pissarro, four hundred by Degas and Sisley, and two hundred by Manet. No single exhibition or catalog could hope to represent such activity comprehensively, yet the choice of works and their installation in both London and Philadelphia admirably evoked the strategies that Durand-Ruel employed in securing Impressionism’s uncertain ascendancy.

While many of the Impressionists, in their later, prosperous years, readily acknowledged their debt to Durand-Ruel—Monet confided to the dealer René Gimpel that “he alone had made it possible for me to eat when I was hungry”—their relationship with him remained quite formal and businesslike. They expected him to perform a number of services, chiefly financial, such as paying rents, renewing insurance policies, and taking care of charitable donations. Louisine Havemeyer, the great American collector of Impressionism, remarked that “Degas looked upon Durand-Ruel as upon a bank account.”

Yet with longevity came loyalty and respect. Degas and Puvis de Chavannes appeared as witnesses at the weddings of Durand-Ruel’s two daughters (in May and September 1893), and at that of his eldest son, Joseph, in September 1896. Renoir asked Durand-Ruel’s youngest son, Georges, to be the godfather to Jean—the future filmmaker—who was christened in the summer of 1895.

Despite his unwavering attachment to several of the founding fathers of Impressionism, Durand-Ruel was less than wholehearted in his admiration for Cézanne, whose reputation he considered “terribly overrated.” He complained to Renoir in April 1908 of “those fools who claim that there are only three great masters, Cézanne, Gauguin, and Van Gogh, and who have unfortunately succeeded in mystifying the public accordingly.” And while his gallery was the first to show works by Gauguin (November 1893), Redon (March 1894), and Bonnard (January 1896), his interest in the Neo-Impressionists and Postimpressionists was negligible compared to his support for the somewhat tepid Impressionism of Albert André, Georges d’Espagnat, and Maxime Mauffra.

In a passage from his Memoirs, the dealer recognized how Impressionism, this new and truly radical art, had struggled to impose itself, a transformation that had taken place during his lifetime:

Time has done its work, and perhaps the colors have softened somewhat, but above all the eyes of the staunchest detractors have become accustomed to these refined, delicate visions of nature that they had not been able to see themselves when strolling through the countryside, and that very few artists troubled to study or sought to convey. Thus they are amazed when they are reminded of their earlier unfairness, when it is pointed out to them that the paintings they admire today are the very ones they formerly found dreadful, that made them stagger with laughter.12

Along with such acute observations about changing taste, what emerges from the story of Durand-Ruel is the way that dealing in contemporary art became a huge, sometimes risky, but immensely profitable business. Very little that takes place in the market for contemporary art today was not anticipated in the career of Durand-Ruel.

-

1

“Celui dont on ne parlait jamais sinon entre spécialistes,” from Pierre Assouline, Grâces lui soient rendues: Paul Durand-Ruel, le marchand des impressionistes (Paris: Plon, 2002), p. 13. ↩

-

2

This painting, acquired by the Philadelphian collector William Hood Stewart (1820–1897), recently appeared at Sotheby’s, New York, November 10, 1998, lot 171, where it sold for $23,000—a fraction of the amount that Durand-Ruel had paid for it. ↩

-

3

Through Monet’s efforts, it was eventually purchased by subscription from Manet’s widow in March 1890 for 19,415 francs, and accepted by the Musée de Luxembourg. Among dozens of subscribers from the art world, Monet contributed one thousand francs, Durand-Ruel eight hundred francs. (Renoir could only afford to send fifty francs.) ↩

-

4

Still Life with Peonies and Poppies (1872; Kunsthalle Mannheim), the second work by Renoir that Durand-Ruel acquired, in May 1872, is as close to Delacroix’s flower paintings as any in Renoir’s repertory. This may have accounted for its appeal. ↩

-

5

Durand-Ruel may have viewed this artist-led initiative as competition; to the “Eighth Exhibition of the Society of French Artists” that opened on April 27, 1874, in the German Gallery—the London branch of his business—he lent four paintings by Pissarro, three by Monet and Sisley, and one by Morisot. ↩

-

6

In his Memoirs, he claimed to have offered the rooms to the Impressionists gratis. ↩

-

7

Three quarters of Monet’s annual income of 31,000 for 1882 came from sales made to Durand-Ruel. See Sylvie Patry, “Durand-Ruel and the Impressionists’ Solo Exhibitions of 1883” in Inventing Impressionism, p. 104. ↩

-

8

In his Memoirs, Durand-Ruel claimed to have organized this show anonymously, “in the former premises of the Valentino concerts on rue Saint-Honoré, which I rented for two months at my own expense.” Joel Isaacson was skeptical of this, noting that the rental fee of 6,000 francs was more likely covered by the engineer (and early collector of Impressionism), Henri Rouart. See Joel Isaacson, “The Painters Called Impressionists,” in The New Painting: Impressionism 1874–1886, edited by Charles S. Moffett (Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco, 1986), p. 376. ↩

-

9

From 1889 to 1893 Durand-Ruel was located at 315 Fifth Avenue (at 32nd Street); between 1894 and 1904, the gallery occupied luxurious premises at 389 Fifth Avenue (at 36th Street) owned by the sugar king H.O. Havemeyer, husband of the most voracious collector of Impressionist painting, who charged the dealer an annual rent of $25,000. In 1913, Durand-Ruel commissioned Carrère and Hastings—architects of the New York Public Library—to design an eight-story gallery at 12 East 57th Street. Hastings would receive the commission to build Henry Clay Frick’s residence at 1 East 70th Street the following year. ↩

-

10

Emile Zola, Carnets d’Enquêtes: Une Ethnographie inédite de la France, edited by Henri Mitterand (Paris: Plon, 1986), pp. 237–245. Guillemet used the phrase “le coup de fêlure pour les Impressionistes.” ↩

-

11

Zola, Carnets d’Enquêtes, p. 244: “Se toque pour Monet, achète et achète encore, en espérant que ça se vendra un jour. Une conviction, il met tout l’argent qu’il a, tout celui qu’il peut trouver…. Toutes les ébauches que Monet lui donne: un puits, un gouffre. Aussi Monet veut-il à Pissarro, à Sisley et aux autres: ‘Si j’étais tout seul!’” ↩

-

12

This beautiful passage was inspired by his reminiscence of the second Impressionist exhibition of 1876. ↩