The fortress of Machaerus in the Jordanian desert has stood in ruins ever since the Romans razed it in the year 72. But even in its heyday, Machaerus was nothing more than a grim hilltop fort overlooking the eastern shore of the Dead Sea, its four watchtowers keeping a wary eye on Petra to the south and Philadelphia (today’s Amman) to the north. It was the perfect place to lock a troublemaker in prison and hope that the world would forget about him.

Sometime around the year 30, in the reign of the emperor Tiberius, the puppet ruler Herod Antipas, tetrarch of Galilee and Peraea, began to worry about the presence of just such a troublemaker on the western border of his territories: a fellow Jew named Jochanaan, an ascetic preacher, had begun to offer people purification by bathing them in the waters of the Jordan River. The man’s wild eloquence was drawing crowds of followers, including a young Jew named Yeshua bar Joseph, who would soon be gathering his own band of disciples. Jochanaan’s message seems to have had political as well as spiritual overtones, or at least Herod thought so. And so the tetrarch arrested Jochanaan, took him as a prisoner to remote Machaerus, and there had him put to death. It should have been a quick assassination, a provincial despot’s quiet purge of a minor local demagogue. Instead, the slaying of the man we know as John the Baptist unleashed forces of incalculable power.

The incident receives brief mention in the book called Jewish Antiquities, written by the Roman Jewish historian Flavius Josephus in the 90s, some sixty years after the events he describes. Josephus also mentions Herod’s stepdaughter Salomé, a perfectly proper princess who eventually reigned as queen of Armenia. Not a whisper of scandal attaches to her name, although her mother, Herodias, had excited gossip—and the Baptist’s vocal disapproval—when she married Herod Antipas after divorcing his brother. Two other early accounts of the Baptist’s death, however, pin blame for his beheading on the daughter Herodias had borne with her first husband.* The more detailed version of the story comes from the Gospel of Mark, paralleled in briefer form by the Gospel of Matthew:

And when a convenient day was come, that Herod on his birthday made a supper to his lords, high captains, and chief estates of Galilee;

And when the daughter of the said Herodias came in, and danced, and pleased Herod and them that sat with him, the king said unto the damsel, Ask of me whatsoever thou wilt, and I will give it thee.

And he sware unto her, Whatsoever thou shalt ask of me, I will give it thee, unto the half of my kingdom.

And she went forth, and said unto her mother, What shall I ask? And she said, The head of John the Baptist.

And she came in straightway with haste unto the king, and asked, saying, I will that thou give me by and by in a charger the head of John the Baptist.

And the king was exceeding sorry; yet for his oath’s sake, and for their sakes which sat with him, he would not reject her.

And immediately the king sent an executioner, and commanded his head to be brought: and he went and beheaded him in the prison,

and brought his head in a charger, and gave it to the damsel: and the damsel gave it to her mother.

But then something extraordinary happened. The followers of the Baptist gathered up his body, buried it, and brought the news back from Machaerus to Galilee, to that Yeshua bar Joseph who had also been bathed by Jochanaan in the River Jordan. Mark continues:

And he said unto them, Come ye yourselves apart into a desert place, and rest a while: for there were many coming and going, and they had no leisure so much as to eat.

And they departed into a desert place by ship privately.

And the people saw them departing, and many knew him, and ran afoot thither out of all cities, and outwent them, and came together unto him.

And Jesus, when he came out, saw much people, and was moved with compassion toward them, because they were as sheep not having a shepherd: and he began to teach them many things…

And he commanded them to make all sit down by companies upon the green grass.

And they sat down in ranks, by hundreds, and by fifties.

And when he had taken the five loaves and the two fishes, he looked up to heaven, and blessed, and brake the loaves, and gave them to his disciples to set before them; and the two fishes divided he among them all.

And they did all eat, and were filled.

And they took up twelve baskets full of the fragments, and of the fishes.

And they that did eat of the loaves were about five thousand men.

In Mark’s telling and Matthew’s, these two events, the slaying of John the Baptist and the miracle of the loaves and fishes, are integral parts of a single story. Not only did the lost sheep of John the Baptist find their Good Shepherd—this is the outcome that Mark and Matthew both mean to emphasize—but also, from Machaerus to Galilee, the death of the Baptist lit the spark of revolution, just as Herod had feared. In the year 39, the tetrarch lost his realm and was banished to Gaul by the emperor Caligula. Josephus declares that Herod Antipas traced his misfortunes straight back to the fact that he had murdered a righteous man.

Advertisement

Then, in 66, the whole of Judaea revolted against the Romans, leading to seven years of brutal war that ended—at least temporarily—with the destruction of the Temple in Jerusalem, the mass suicide at the fortress of Masada, and the demolition of Machaerus. By that time, however, the influence of the two men from Galilee had penetrated to the heart of Rome itself. In 64, after a devastating fire had swept the city, the emperor Nero, in the words of the historian Tacitus,

fastened the guilt and inflicted the most exquisite tortures on a class hated for their abominations, called Christians by the populace. Christus, from whom the name had its origin, suffered the extreme penalty during the reign of Tiberius at the hands of one of our procurators, Pontius Pilatus.

Pontius Pilate had no better success with his policy of repression than Herod Antipas. He was forced to retire from Judaea in 37, two years before Herod’s disgrace.

It is this embattled Holy Land, with its merciless landscape, its perpetually treacherous political situation, its religious charge, and its profound connections to the present day, that provides the driving force for Salomé, a new production created by Yaël Farber for the Women’s Voices Theater Festival in Washington, D.C. Her new vision could not be more welcome. The Salomé we know best, the fin-de-siècle temptress who haunted Gustave Flaubert, Gustave Moreau, Oscar Wilde, and Richard Strauss, came into being at the turn of the nineteenth century into the twentieth, in a steamy Freudian blend of sex and Orientalist fantasy that has become its own historical moment.

By the time he composed his one-act play in French for Sarah Bernhardt in a Paris hotel in 1891, Oscar Wilde had become tangled in his own web of sexuality, figuratively losing his head over young, blond Alfred Lord Douglas, who subsequently translated the original text of Salomé into an English strikingly devoid of Wilde’s coruscating wit. With a hundred years of hindsight, Salomé’s yearning to kiss Jokanaan’s red mouth sounds suspiciously like the author’s own yearning after the red mouth of “Bosie,” a thrall to the love that dared not speak its name:

I love thee yet, Jokanaan, I love thee only…. I am athirst for thy beauty; I am hungry for thy body; and neither wine nor fruits can appease my desire. What shall I do now, Jokanaan? Neither the floods nor the great waters can quench my passion. I was a princess, and thou didst scorn me. I was a virgin, and thou didst take my virginity from me. I was chaste, and thou didst fill my veins with fire…. Ah! ah! wherefore didst thou not look at me, Jokanaan? If thou hadst looked at me thou hadst loved me. Well I know that thou wouldst have loved me, and the mystery of love is greater than the mystery of death. Love only should one consider.

But Oscar Wilde, though prone to folly, was no fool, and Farber weaves extracts of his symbol-laden drama into a script that also borrows from the gospels, Josephus, the Hebrew Bible, and the Mesopotamian sacred text that describes the descent of the goddess Inanna into the underworld. What dominates this gripping new production, however, is the physical feel of Judaea, a place made of rock, sand, and sun, where water is a precious rarity and human cruelty is more than a match for the ruthlessness of the land itself.

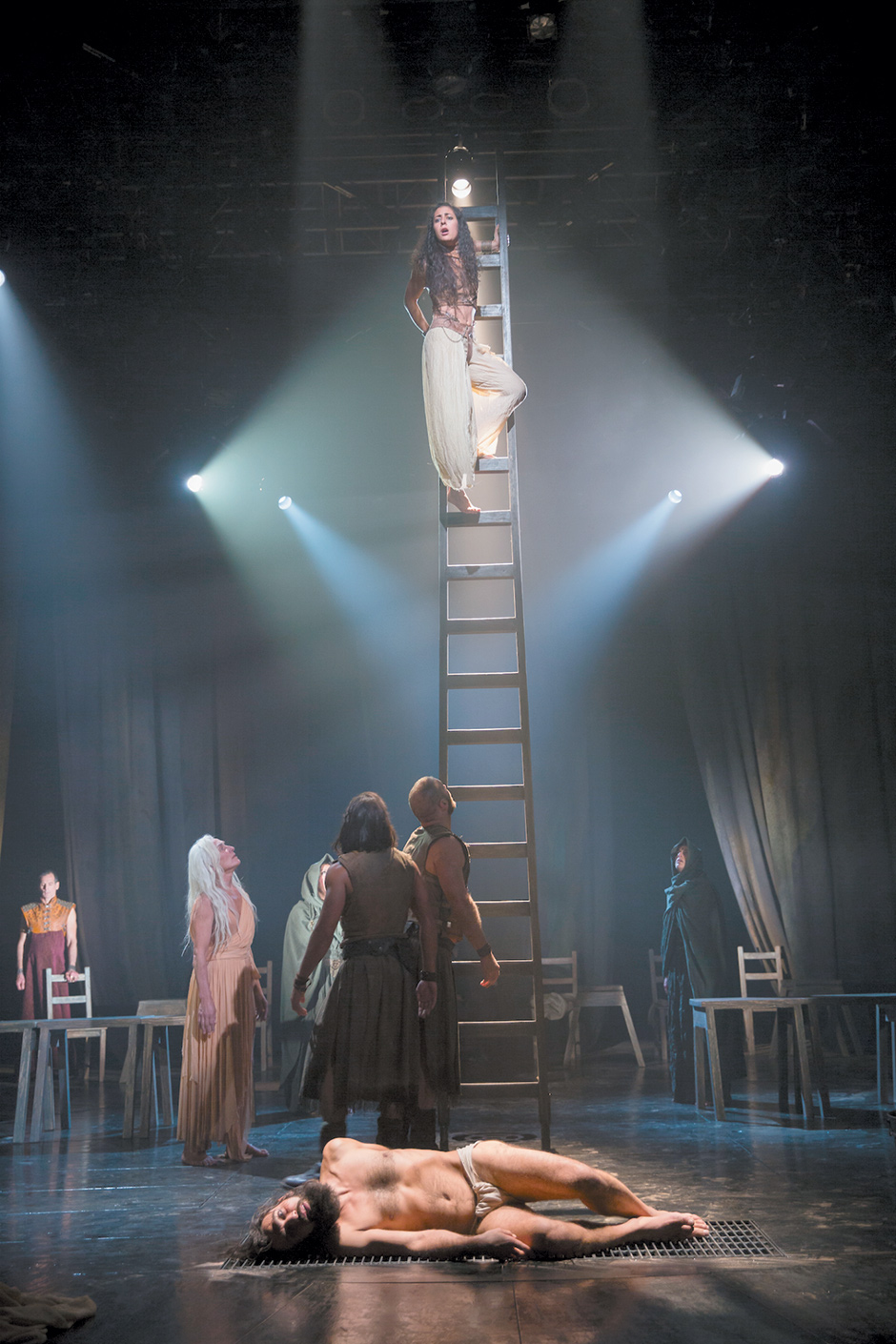

The stage has been stripped to the walls and painted black. Within this space, a ladder, a dozen chairs, sand, drapes, a sunken trough, lights, and a revolving stage are enough to create the Holy Land in our imaginations, from the banqueting room of Machaerus to the torture chamber where Salomé is interrogated by Pontius Pilate and his thugs, convinced that a young woman could never have plotted the death of the Baptist herself. A sudden shower of golden sand transports us to the desert, and when a parade of ordinary people wades through the onstage trough of water under the piercing gaze of Jokanaan (the remarkable Syrian actor Ramzi Choukair), we can gain some feel for what the strange, simple act of baptism must have meant on the edge of the desert. And throughout the action, two women singers, Lubana Al Quntar and Tamar Ilana, provide a hauntingly beautiful obbligato that keeps us securely in the Middle East.

Advertisement

Farber splits Salomé into two separate figures: the young princess (Nadine Malouf) and her older self, called the Nameless Woman (a fiercely gorgeous Olwen Fouéré). Ever since the murder of Jokanaan, she has been confined to a subterranean prison beneath the city of Jerusalem, just as the Baptist himself was once imprisoned in an underground cistern within the fortress of Machaerus. It is this Nameless Woman, the play’s charismatic narrator, who spins out Salomé’s dread tale in her resonant voice. Buried alive beneath the Temple Mount of Jerusalem, she has become the earth mother this harsh land would necessarily produce. Herodias has dropped out of the story entirely, but Herod Antipas is present as a lecherous drunk (played with tipsy gusto by Ismael Kanater), exactly the kind of man who could offer a dancing girl half his kingdom—but why would he not, when ruling it meant trying to appease the Romans on one hand and the Jewish traditionalists on the other?

The play revolves around the idea that the murder of Jokanaan, John the Baptist, is an act with tremendous political consequences and that Salomé undertakes it because she, Jokanaan, and Herod all know that the Baptist’s death will spur the Jews to rebel against the tyranny of Rome. T. Ryder Smith’s cruelly practical Pontius Pilate is certainly the kind of Roman to inspire rebellion: a procurator who levies taxes for aqueducts when he is not torturing rebels. The high priests of the Temple, meanwhile, are too worried about offending their two vengeful masters, God and Caesar, to mount a credible opposition to the Romans.

Above this incessant political and religious chatter, two eccentric voices proclaim visions that rise above the noise. They are the prophet Jokanaan, who wears a loincloth as if it were a fine robe and declaims in Arabic (most of it immediately translated by the Nameless Woman), and the huddled creature called Yeshua the Madman (Richard Saudek). Yeshua the Madman is not Jesus; he lived in Jerusalem a generation after Jesus, in the days preceding the Jewish Revolt of 66. He is dressed for this production like the homeless man who in real life stations himself outside the Shakespeare Theatre every day, wrapped in the same burlap shroud, surrounded by stuffed animals, rocking gently as he talks to himself. In the staged world of Salomé, Yeshua the Madman cries out the doom of Jerusalem just as Josephus says he did (and Yeshua was right on that account), but Farber’s madman also tells the tale of the loaves and fishes from the Gospel of Mark. In Roman Judaea, everyone seems to be a prisoner, and everyone seems to be crazy except the wild-eyed prophet in the loincloth, who attracts Herod’s stepdaughter as magnetically as he has attracted humble people.

In this version of Salomé, the princess actually climbs into the cistern where Jokanaan is imprisoned, a vertiginous journey down a ladder so high and rickety that it drew gasps from the audience. Here, as the Nameless Woman recites the Babylonian Descent of Inanna, she sheds her garments and jewels as she enters seven successive gates, standing naked before being wrapped in a white dress. When the Baptist sees her, he bursts not into the abuse we hear in Wilde and Strauss, but into the tender poetry of the Song of Songs. Malouf is a beautiful woman, but with a strong, sturdy Eastern beauty; when Jokanaan says, “Thy neck is like the tower of David builded for an armoury, whereon there hang a thousand bucklers, all shields of mighty men,” we can believe the military imagery. Together in the Baptist’s prison cell, they become the Adam and Eve of a new era. When Salomé climbs out of the cistern to face her stepfather’s banquet, it is with a radiant sense of purpose.

Oscar Wilde was the first to call Salomé’s dance for Herod the Dance of the Seven Veils, although his spare stage directions omit any information about what form that performance was supposed to take. Aubrey Beardsley would illustrate it, with Wilde’s enthusiastic approval, as a “stomach dance,” for belly dancing and various forms of “Oriental dance” were all the rage in the London of the 1890s. Turned into a striptease, the Dance of the Seven Veils provided an intense dramatic focus for Richard Strauss in his opera of 1905, and has presented a stiff challenge for many a talented soprano (Montserrat Caballé, mischievous as ever in her statuesque maturity, recalled scampering around the stage “before I got big”).

The Seven Veils in Farber’s Salomé are not articles of clothing but the floor-length drapes of Herod’s banqueting hall, and when she begins to dance with them, in a spectacular turn, she brings to mind Samson pulling down the palace on his Philistine tormentors. When the Baptist’s head falls at the end of the spectacle, the Nameless Woman stands by, sword and basin in hand, like an avenging Judith, and Jokanaan poses for a time in the posture of Caravaggio’s great Beheading of Saint John the Baptist in Malta. Susan Hilferty’s scenic design is as deeply informed as Farber’s script, while at the same time presenting tableaux of striking novelty.

The end of Salomé’s story is, necessarily, brutal. It is inconceivable to Pontius Pilate that she could have acted alone, but after failing to torture the “truth” out of her, he can only condemn her, transformed into the Nameless Woman, to life imprisonment beneath the Temple Mount as the history she has helped to push forward continues to unfold above her head. Here Farber’s Salomé passes definitively into the realm of myth; her real-life counterpart, the real Salomé, was bringing up her three sons in the region of Aleppo in present-day Syria, sons who would dissolve into the great melting pot of the Roman Empire. If there were daughters, too, we know nothing about them.

Washington, that most political of cities, was quick to recognize the ways in which this new retelling of Salomé’s story might connect with current events, although, like any profound work of art, it does so in complex, suggestive ways rather than by offering simple parallels (the fact that Jokanaan speaks Arabic does not automatically make him a contemporary Palestinian). And what explains the persistence of Wilde’s interpretation of Salomé’s character, which has certainly outlived his play? Perhaps it is the fact that he adapted a much older story. The vision of Salomé the temptress seems to have arisen in twelfth-century Europe, when she features as a voluptuous dancer in Romanesque churches on either side of the Pyrenees, in Spain and southern France, a perennial symbol of lust.

In a similar vein, Renaissance painters from Filippo Lippi to Titian to Caravaggio return to her repeatedly, puzzling over the motives behind her gruesome request for the Baptist’s head, focusing sometimes on her graceful body, sometimes on her enigmatic face, contrasting the girl’s pleasing lines with the violent destruction of the Baptist’s physical integrity. It is Caravaggio who brings the princess back into her weighty historical setting, imagining Salomé as a young woman who suddenly begins to grasp the full tragedy of what she has set into motion: for Caravaggio, this means the Baptist’s experience of life and death, but also the whole Christian mystery of the suffering mortal who becomes a cosmic king, and John his forerunner.

Caravaggio painted the Baptist’s death on a huge canvas for the private chapel of the Knights of Malta in Valletta, signing his own name in the prophet’s spilled blood as he prepared to join the religious order established in the Baptist’s name. In his felled prophet, hunched awkwardly on a barren pavement, we see both the glorious body of a man in his prime and the dreadful vulnerability of that body to ordinary human malevolence. On Malta’s arid limestone plateau, it is this sad, compassionate painter whose vision of the last days of John the Baptist comes closest to envisioning the realities of the blasted rock fort of Machaerus, and also shares a deep bond with the stunning theatrical vision of this tragic story that Yaël Farber has granted us.

-

*

Some manuscripts of Mark give the girl’s name as Herodias. ↩