And all the rest of her a shifting change,

A broken bundle of mirrors…!

—Ezra Pound, “Near Perigord”

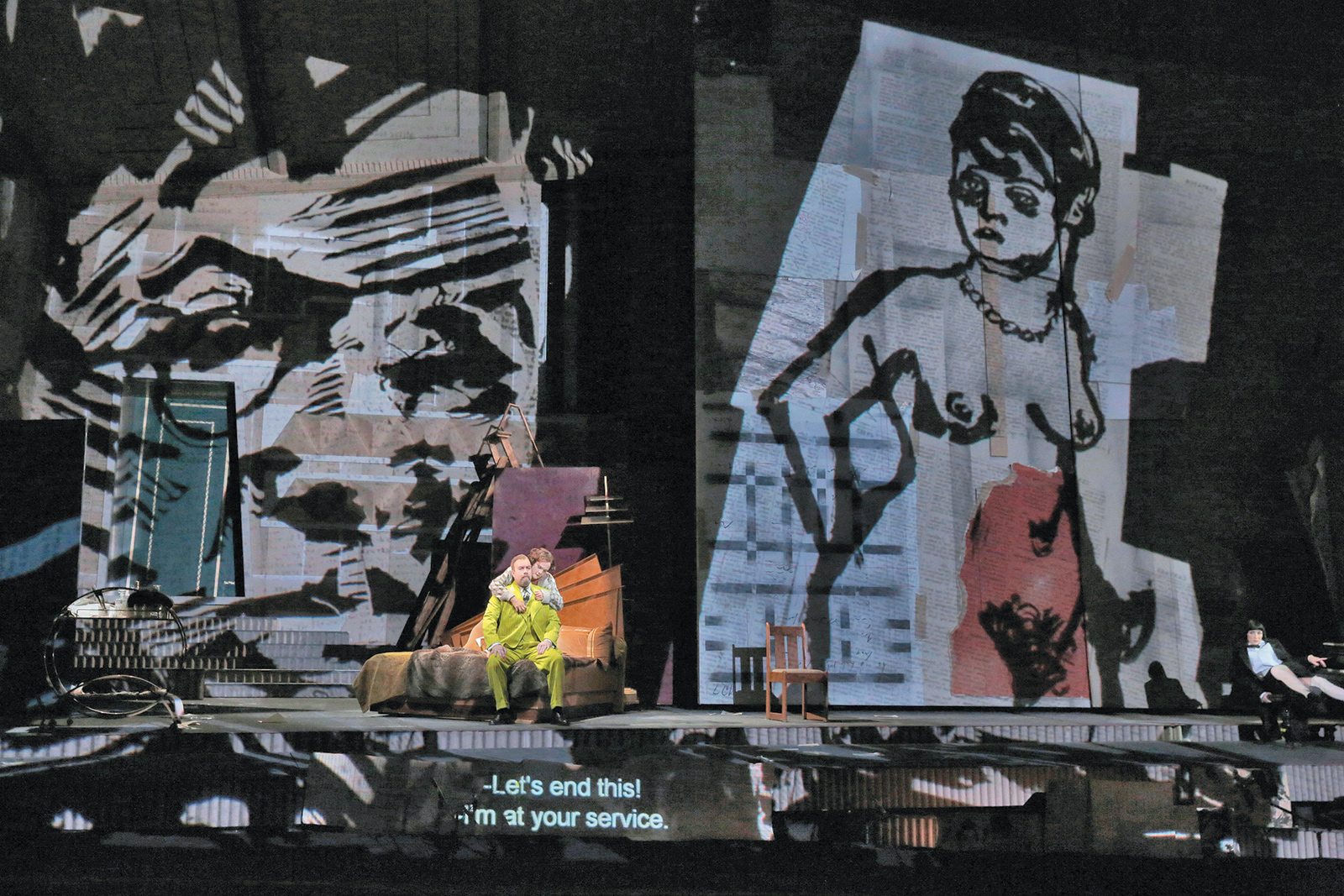

A sketch of a standing woman, half-naked, bending to the side as if posing on demand, the eyes downcast and the lips frowning, brushed in black ink by William Kentridge, is hoisted in front of the Met to announce Kentridge’s new production of Alban Berg’s opera Lulu. It is not a solidly imposing image, not a by now familiar memento of a historic era (like, say, a blow-up of Louise Brooks playing Lulu in G.W. Pabst’s 1929 film Pandora’s Box), but rather something that as light passes through it seems to go in and out of visibility: an immense transparency, wraith as pin-up, never quite here, never quite gone.

It is Kentridge’s second round at the Met. His production of Dmitri Shostakovich’s The Nose five years ago was an extravagant debut, using the spaces of the Met stage with freewheeling invention and bombarding the audience with visual stimuli at a pace almost impossible to consciously track, as if we were being given not merely an interpretation of The Nose but a palimpsest of myriad interpretations unfolding simultaneously. The youthful bravado of Shostakovich’s work clearly lent itself to such an approach. Some wondered in advance if Kentridge’s characteristically overflowing style might not risk getting in the way of the compressed complexities of Berg’s Lulu.

Overflow is an unavoidable image in thinking about Kentridge. Where to begin with him? Or does it matter? Over and again the work seems to suggest otherwise. Anywhere we dip in we find ourselves amid “a cacophony of information always rebeginning,” to borrow a phrase from the first of the Charles Eliot Norton Lectures that he delivered at Harvard in 2012.1 With Kentridge the rebeginning is indeed perpetual. No sooner does he give a shape to something than it generates further evolutions and spinoffs, whether in the form of drawings or animations or live-action films or operas or books or lectures, the Norton Lectures themselves spilling well beyond the ordinary limits of the genre, making free use of image and gesture and sound and silence. Kentridge’s works, in all their varieties, exist not separately but in lively communication, or perhaps mutual infiltration, with one another. Securely walled-off borders are not to be found.

This fall, during the lead-up to Lulu, Kentridge’s work seemed to be everywhere around New York. We have had elaborate volumes surveying two of his long-term projects: a series of drawings executed on the pages of the 1906 account book of a South African gold mine and the cycle of animated films charting the imagined life of a Johannesburg entrepreneur who becomes a sort of alter ego for the artist2; an exhibition at the Marian Goodman Gallery in which the walls were covered in seemingly anarchic profusion with some of the drawings made for Lulu; from Arion Press a limited edition of Frank Wedekind’s Lulu Plays (Earth Spirit and Pandora’s Box, the two plays so brilliantly condensed by Berg for his libretto) with sixty-seven brush-and-ink drawings by Kentridge; not to mention another opera, Refuse the Hour, an eighty-minute work (based on his earlier video installation The Refusal of Time) written and conceived by Kentridge with music by Philip Miller, produced at the Brooklyn Academy of Music in October.

“Opera” was to be taken in the broadest sense, as Refuse the Hour contained, along with singers and instruments, a lecturer (Kentridge) discoursing on the nature of time and other matters, including the myth of Perseus; visual displays of chronographic devices; a good deal of slapstick; and, centrally, a powerful dance performance by the South African choreographer Dada Masilo, all in the service of demonstrating that “we are breathing talking clocks” whose lives consist of “one big wind-up at birth and then a slow winding down.” The actual subject of Refuse the Hour seemed to be the refusal—by setting in motion multiple alternate ways of measuring (or expanding, or ignoring) time—of the hour and twenty minutes the work took to perform.

I say “seemed” because Kentridge is an inspired explainer—pointed, deeply humorous, playing in surprising ways on the resources of philosophy and history and science—who makes a point of explaining nothing. He speaks of art as providing “a safe space for uncertainty.” Each moment in his always unfolding argument is a leaping-off point toward the next leaping-off point. Each image is there to provoke “our thinking about ourselves, our awareness of ourselves as looking.” The mood of his work is of a restless and wide-awake curiosity and intelligence making a place for itself in the world through art, a place not sealed off but constantly opening new vantage points from which to spy out what is going on, which as a matter of course includes what has been going on, as far back as Plato or further if necessary.

Advertisement

Art for Kentridge is identified with drawing—“the activity I practice”—and whatever he does is an extension of that activity, never more so than in the present production of Lulu. Each drawing is a proposition that leads to flurries of further propositions. None is quite nailed down; they continually squirm and recombine. Through animation they begin to move and through projection they become a theatrical event, but the original point of contact is never lost. The projections at the Met include Kentridge’s own hand executing thick black calligraphic lines, lines that sometimes become Lulu and sometimes, when they are most dense with ink, become great splotches of blood.

Fixed to the wall of the Marian Goodman Gallery, strewn about in chaotic constellations, the Lulu drawings seemed ripped unwillingly from the flux of which they were part. Here were the building blocks of his production: images with the density of Expressionist woodcuts, steeped in the history of Frank Wedekind’s time and of Alban Berg’s, “translations,” as Kentridge puts it, “from Beckmann, Kirchner, Klimt, Nolde, Kollwitz, as well as images from documentary and the fictional films of the period,” brushed on the pages of an old dictionary whose words show through the faces. It did indeed seem like a partial lexicon of what was once the modern world: a silk hat, a dressing gown for an aristocrat, the hairstyles of psychologists and art critics, head shots of prisoners with their numbers, gas masks, dancing couples, gramophones, a cholera ward, a brownshirted guard, a steamer bound for Cairo.

And faces, some enlisting celebrities of those eras as cast members: Richard Strauss as the Banker, Gustav Mahler as the Marquis who tries to sell Lulu to an Egyptian brothel, Leni Riefenstahl as her lesbian admirer Countess Geschwitz, Sigmund Freud (who else) as the Theater Manager, and Alban Berg as Alwa, the young man enraptured with Lulu who in Berg’s libretto is a composer and his own mirror image, singing toward the end of the first act: “What an interesting opera could be made about her!” Anonymous faces in a Weimar crowd: flattened, mesmerized, angry. They could be incipient killers or astonished witnesses of a killing. And Lulu: her face, her body clothed, her body naked, pieces of her cut out and juxtaposed like a disassembled jigsaw puzzle, Lulu reimagined and reconfigured over and over as an advertisement or an erotic artifact or a wanted poster or a photograph of a murder victim from the archives of a police morgue.

The impression is of a vortex of images from the past, as if it were necessary to plunge downward and backward—into the land of the dead—to find the heart of Lulu. As if Lulu (“created to spread misfortune…killing without a trace,” as the Ringmaster introduces her in the prologue) were inextricably a mythological creature from another age, connected to some harrowing but now extinct religious practice. (Wedekind did in fact first call his character Astarte.)

At this distance Lulu runs the risk of becoming indistinguishable from some nearly Theda Bara–like poster image of the Fatal Woman, a vast and doubtful abstraction, the end result of a kaleidoscopic mélange of elements drawn from Heine’s Lorelei, Wagner’s Kundry, Zola’s Nana, Wilde’s and Strauss’s Salomé, the whole overripe gallery of decadent imagery of demonic devourers typified by the serpent-wrapped woman embodying “Sensuality” in Franz von Stuck’s 1897 painting, all the way down through Marlene Dietrich’s Lola Lola in The Blue Angel (1930).

It’s easy enough to argue that Wedekind (1864–1918), an outspoken proponent of sexual freedom as he understood it, didn’t intend a cautionary tract against the perils of unleashed female sexuality. It is harder to define what precisely he did intend by his central personage, or how his intentions may have changed during the years he developed the character, from the five-act play he wrote in Paris in the early 1890s under the title Lulu: A Monster Tragedy to the expanded and greatly altered two-part version published as Earth Spirit (1895) and Pandora’s Box (1904).3 The first Lulu is a considerably coarser, wilder, more wide-open work; if the latter two plays could not be publicly performed in Wedekind’s lifetime, the first might not have been legally publishable. He had already written the likewise initially unstageable Spring’s Awakening, putting adolescent sexuality and its harsh repression by society on stage in unprecedented fashion.

The first Lulu goes further in creating a dramatic space in which society itself seems to dissolve under the pressures of desire and we are left with beings who shift personalities at every moment as their instincts toss them about. Splendidly furnished bourgeois drawing rooms become arenas for seduction scenes staged in a mood of brutalist slapstick porn: Alwa, sharing a snack with Lulu, is excited by “your little hands fingering the asparagus,” tells her that “unless you intend to make a sex murderer out of me, I must give immediate expression to the ecstasy I feel!” and later recounts how “I made love to her the first time in her bridal dress, the day of her wedding with Papa, she’d got the two of us mixed up.”

Advertisement

The plot and many of the dramatic high points are broadly the same as in the revision: we get Lulu’s first husband dropping dead when he finds her making love to the artist painting her portrait; the painter marrying her and then cutting his throat when he learns of her early sexual behavior (here, she is already being prostituted at seven); her marriage to the doctor (Berg’s Dr. Schön) who had kept her throughout her youth; his jealousy at her many lovers and suitors; her shooting Schön after he tries to induce her to commit suicide; her flight and eventual descent to the status of a London streetwalker and her murder at the hands of Jack the Ripper. The tone, though, is far more grotesque and flagrantly assaultive on prevailing literary manners. It is a violent Punch and Judy show to be enacted by humans, steeped in the noise and shock effects of circuses, cabarets, and those brothel entertainments of which Wedekind has left some description in his diaries.4

The revised versions of the Lulu plays could be called “toned down” only by comparison with the rawness of where Wedekind starts from. By main force he is trying to put on stage what cannot be shown. The violence of that effort is reflected in what seem the monstrous exaggerations and unbelievably volatile turns of the plot—those moments in which ordinary reality seems to explode before our eyes—moments that on a closer look at Wedekind’s own life and era turn out to be scarcely exaggerated or unbelievable at all.

The diaries are a more or less dry and undramatized account of his doings in Berlin, Munich, and (mainly) Paris in the years when he wrote his most famous plays, recording a milieu in which litterateurs (like his distinguished friend Gerhart Hauptmann) cultivate their careers while swapping gossip about the latest suicide and worrying obsessively about syphilis; and Wedekind pursues with almost monastic devotion (sleeping only when forced by utter physical exhaustion) a lifestyle of scrounging and debauchery, days and nights collapsing into each other as a series of women—courtesans, streetwalkers, café entertainers—come and go in his rented room. A morphine addict dances barefoot at the Moulin Rouge, an Alexandrian belly dancer fluent in Russian and German performs while Wedekind accompanies her on the mandolin, and there is a constant flow of books and talk about their authors: Zola, Loti, Sacher-Masoch (Wedekind contemplates sending a copy of Spring’s Awakening to the author of Venus in Furs), Hamsun (whom he just misses running into at a publisher’s office), Strindberg (whose wife he later ended up fathering a child with). During the same period he was also reading tracts on women’s rights and Kraft-Ebing’s Psychopathia Sexualis.

Wedekind’s early experience of that demimonde everywhere present yet scarcely nodded to in the public sphere except in the most moralistic terms, his distinctly unsentimental perception of a whole society moving to the rhythms of an unacknowledged sexual dependency, permeate those first and still most famous plays. When Countess Geschwitz, in the last act of Pandora’s Box, states (in a line Berg omitted from his opera) that “men and women are like animals; not one of them knows what he’s doing,” it has the air of a news bulletin.

Later the plays would be recognized as precursors of Expressionism and many another movement, and the devices he fell into—the puppetlike behavior, the dialogue in which everyone talks past one another and enormous gaps of meaning seem to open between the lines, the scenes and characters that break apart before our eyes, the prophetic absurdism of the total effect—would be imitated (as they still are) by generations of playwrights who could see that they were a more direct transcription of the real than the naturalist plays then in vogue.

The Wedekind plays are not simply Berg’s source but his matter. He chisels them into the shape he needs but Wedekind remains at the center, as if enclosed within the immense musical architecture that has been built around his text. Berg in some sense imposes a form on chaos. Reading the plays you can imagine a hundred different registers or tempos for any scene. The opera by contrast is so precise that, as the scholar Douglas Jarman has commented, “almost every aspect of the production is determined by the composer and integrated into the musical structure.”5 The actions have already been delineated with a needle’s point before any director goes to work, and that delineation becomes perceptible even to a listener incapable of parsing the palindromic and recapitulative structures that musicologists have so elaborately charted. Lulu’s characters may be blown about by the deluded imperatives of desire but the musical space in which they drift is rigorously sustained.

What they sing might be taken as what the music forces out of them in an urgent effort to shape the passing moment, to seize hold of what is changing in that very moment. Long as Lulu is, it is also extraordinarily rapid and telegraphic, and many a scene that on stage makes an overwhelming impression—like the dressing room episode where everyone is badgering the recalcitrant Lulu to go back on stage, or the sudden violent end of Dr. Schön—can be measured in a few minutes, sometimes in a few seconds. There is nothing like a time-out in Lulu, never a moment of contemplative detachment even for those artistic types (Schulz the painter or Alwa the composer) deluded enough to think they can step outside the whirl of contingency.

The closest thing to a pause is the interlude at midpoint where we are shown a cinematic summary of the aftermath of Lulu’s shooting of Dr. Schön, as she is tried, condemned, and finally enabled to flee from the hospital where she is ill with cholera. If nothing else we have the chance then to fully apprehend the underlying orchestral power that has been pulsing throughout. In the course of listening to Lulu the ear adapts itself to the shifting tones and discerns an abstract elegance like the patterns made by microbes under a microscope. In the opera’s double vision, the orchestra is the prism through which we perceive those trapped creatures and hear how their fragmentary utterances are part of an encompassing pattern they themselves cannot grasp. There is a claustrophobia of cross-purposes, so that even Lulu, around whom everyone’s desires or purposes swirl, finds herself crowded in her own opera.

But then she is crowded in her own being. Kentridge like many others sees Lulu as the unstable reflection of other people’s desires: “She can’t be the woman the men imagine her to be or project onto her.” In this reading Lulu can be taken scarcely to exist other than as a shifting array of distorting mirrors: appropriated images triggering reactions that always just miss their aim.

From moment to moment she might reveal another contradictory facet, as abused daughter, perverse child, defiant exhibitionist, born fighter, born loser; connoisseur of the pleasures of cruelty; raging, sulking, savoring her own mythomania; yearning for an image of domestic security of whose futility she is already aware; startling a room with some madcap outburst; permanent fugitive, belonging nowhere to no one, devoted to the father figure Schigolch who may well have been her pimp; harboring a possessive love for the man who kept her as his mistress in her youth and whom she will end up killing; seducer of his infatuated son, whose mother she claims to have poisoned, and whom she cannot help but drag along with her to their mutual doom. Or perhaps, settling back into a fundamental indifference finally indistinguishable from a death wish.

The hairpin turns make the role, and here Marlis Petersen (who is appearing as Lulu, a role she has often sung, for the last time) perfectly realized that continual metamorphosis, switching moods and modes with a glance, a gesture, or a swiftly readjusted pose, standing on a sofa or a table, retreating up the ladder as the painter pursues her. One way or another, in the midst of a strong cast, her presence was always dominant. If the production design emphasizes Lulu as an image perceived and manipulated by others, Petersen asserted a being who finds nowhere to rest and in whom no one else can find a resting place. Her constant restless effort to escape the situation she is trapped in—the situation of being herself, of being what everyone wants in order to make themselves complete—was shown as an awkward evasive sliding, a recoiling movement with nowhere to go. Each of her moves—whether signifying seduction or domination or mere contempt—seemed truncated, an overture made and then withdrawn. Her angular shifts of posture had the defiant precision of acrobatic demonstrations.

That angularity became part of Kentridge’s design, in which no gesture or artifact was too small or fleeting to be played off other elements. (Even the black lines on Dr. Schön’s necktie rhymed with the many other such bloodlike splotches.) It is, as anticipated, a production of continual and overflowing invention, starting with the menagerie of animals that accompany the Ringmaster’s opening invitation to the zoo of which Lulu, the serpent-woman, is the centerpiece. As we move with shocking abruptness into the first scene—Berg creates the effect of being dropped roughly into the middle of the action—we are aware of a studio restricted to the far edge of the stage, an artist’s table strewn with papers and paintbrushes, and Lulu posing for her portrait with her head concealed under what looks like a conical lampshade with a crude face drawn on it. In the midst of the large unused portion of the stage, a woman in a tuxedo—one of two mute multipurpose extras whom Kentridge has added to the cast—sits at a piano.

To the paper head the painter will shortly add paper breasts and genitals, attached to Lulu as if nudity were a form of clothing. (Later she will sport enormous paper hands.) In the meantime we are seeing shifting projections of Kentridge’s drawings: faces, bodies, scenes, and settings. Pieces of paper in one form or another are everywhere, whether projected on the stage or tossed about the singers. These images are in constant fluctuation; they change scale, they are set in motion by simple animation, the same image multiplies or is juxtaposed with other images, they are disturbed by the shapes of the objects on which they are projected, they are blown like curtains by the wind.

At certain marionettish moments the singers’ movements are mirrored by the movements of the projected drawings as if everything on stage were being manipulated from above by strings. Giant inkbrushed hips swivel seductively like a come-on for a carnival midway. The distinction between what is projected and what is actually occurring on stage is often lost. We see Kentridge’s hands in the act of making the drawings, as if he were creating them simultaneously with the playing of the opera.

He has taken instability as the theme of his production, and makes sure that nothing remains stable. Rooms change size and form, shrinking to hem people in, or widening to give full scope to Dr. Schön’s paranoia as he peers down from an impossibly elevated height into his own drawing room to find where Lulu has hidden her lovers. No position is fixed, at every instant things are sliding away from where they were meant to be, and people are drifting apart from who they were meant to be. The two mute servant figures pop up along the margins, emerging out of unexpected places, marking an edge that never stops moving around. The basic black of the design is offset by radiant colors in the first half (Dr. Schön’s bright green suit positively lights up the stage), before the Expressionist cartoon Kentridge has provided for the interlude prepares the way for Lulu’s haggard reappearance after her escape, as the opera begins its descent through successive layers of degradation right up to the final slaughter at the hands of Jack the Ripper, a scene played high up in a garret with barely room to move.

It is certainly as personalized a production as can be imagined, handwritten in the sense that Kentridge’s recognizable brushstrokes are everywhere displayed, yet it does not feel like an imposition. Kentridge conducts himself as the obedient servant of the opera, and manages to create the illusion that the music itself is generating the visuals. He has responded to Berg’s music by creating a visual counterscore, not overwhelming it or distracting from it but moving in supple response. The freedom and ragged edges of Kentridge’s effects—their emphasis on fragmentation, the way they expose their own materials—work somehow in seamless collaboration with the music, with the effect of revealing that music’s actual seamlessness (even allowing for Friedrich Cerha’s contribution in filling out the unfinished third act), a quality all the more paradoxical in an opera whose subject matter consists of little but seams, divisions, fault lines, fractures.

The production, like the work, is permeated with history. In the profusion of images we are assailed with traces of that Europe of which the opera is such a pure product, but there is nothing museumlike in that sense of the past and never any doubt that we are in the present moment, even while being given every encouragement to imagine the other places through which Lulu has traveled: Wedekind’s bohemian world of the 1890s, the Weimar era in which Berg began his opera, and the Nazi era in which he attempted to finish it, all leading up to the question of precisely what world we find ourselves in now. We have continually the sense not of passive entrancement but rather of being shaken awake, right up to the moment when, as the lights come up, the projections cease and we look at an astonishingly bare and unadorned stage.

This Issue

January 14, 2016

ISIS in Gaza

How to Cover the One Percent

A Ghost Story

-

1

Videos of the lectures have been posted online by the Mahindra Humanities Center at Harvard. They have been published in book form as Six Drawing Lessons (Harvard University Press, 2014). ↩

-

2

William Kentridge and Rosalind C. Morris, Accounts and Drawings from Underground (Seagull, 2015) and Mathew Kentridge, The Soho Chronicles: 10 Films by William Kentridge (Seagull, 2015). ↩

-

3

The original version has been adapted by Eric Bentley as The First Lulu (Applause Theatre, 1994). ↩

-

4

Frank Wedekind, Diary of an Erotic Life, edited by Gerhard Hay, translated by W.E. Yuill (Blackwell, 1990). ↩

-

5

Douglas Jarman, The Music of Alban Berg (University of California Press, 1985), p. 219. ↩